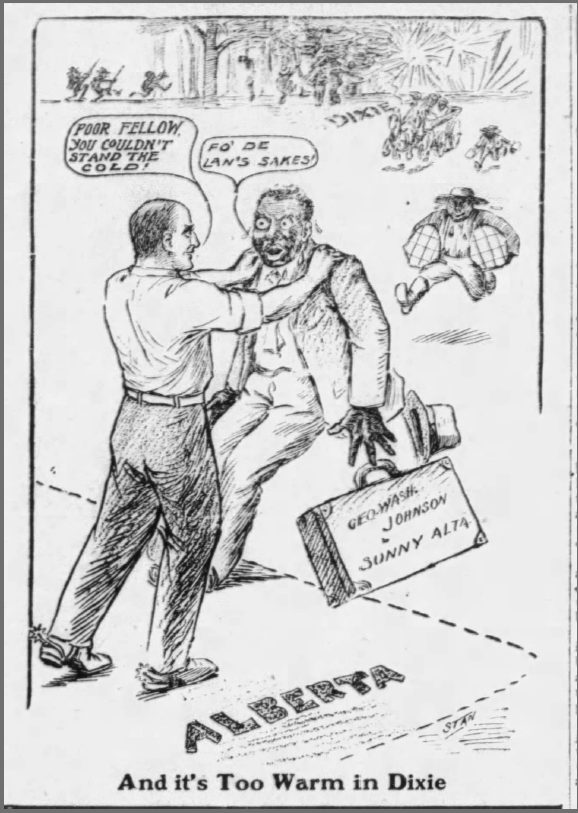

In the early 1900s, Black pioneers in Alberta often saw themselves as proud Canadian citizens and British subjects. However, they faced and fought exclusion from several aspects of Canadian life ranging from serving in the Canadian Expeditionary Forces to local theatres to swimming pools and access to housing.

Charles Daniels: Denied Entry

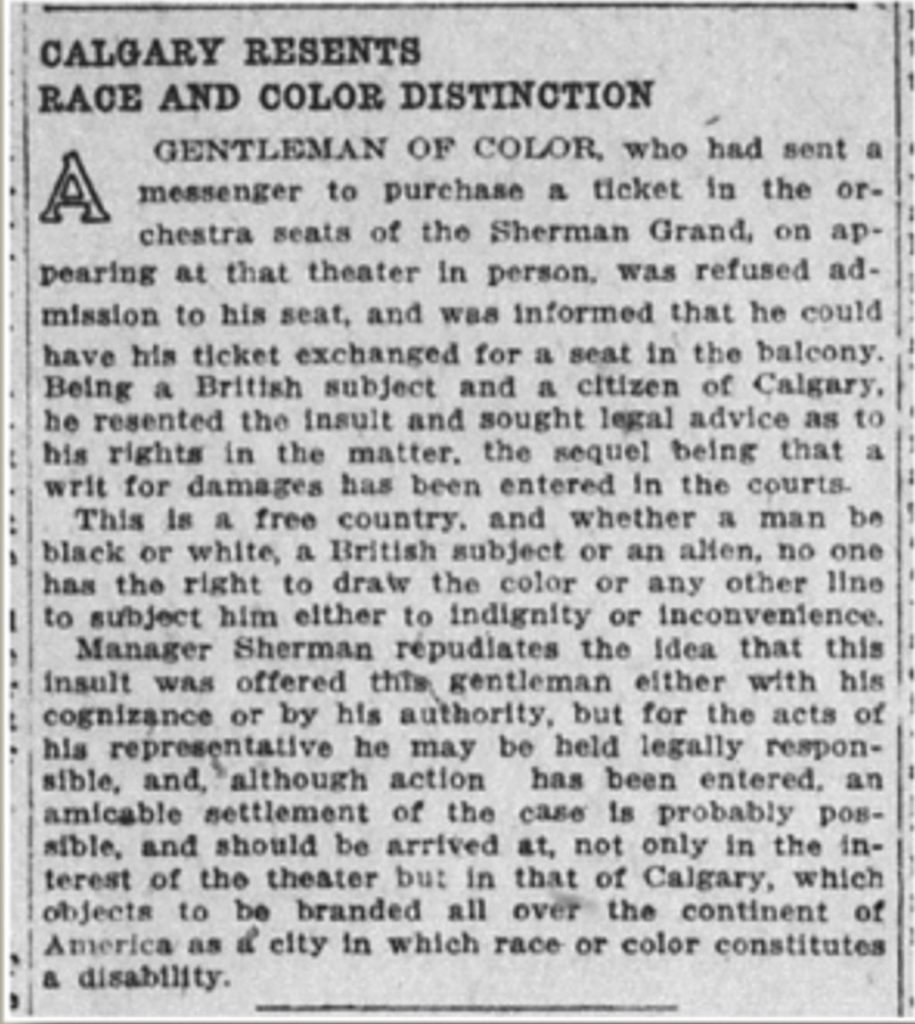

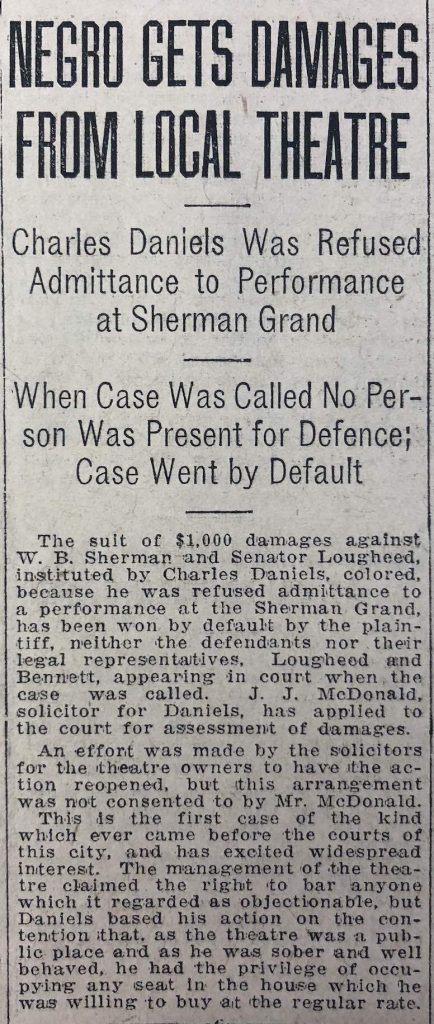

In 1914, Charles Daniels- a sleeping car porter– was denied entry to the front row seats he had purchased at the Sherman Grand Theatre in Calgary and was directed to the “Colored’s Section” on the balcony.

Calgary Resents Race and Color Distinction

“A gentleman of color, who had sent a messenger to purchase a ticket in the orchestra seats of the Sherman Grand, on appearing at the theatre in person, was refused admission to his seat, and was informed that he could have his ticket exchanged for a seat in the balcony. Being a British subject and a citizen of Calgary, he resented the insult and sought legal advice as to his rights in the matter. the [sic] sequel being that a writ for damages has been entered in the courts.”

Calgary News Telegram, 7 February 1914.

Surprisingly, Daniels was able to sue the theatre’s management for $1,000 in damages for the public humiliation the incident caused him. However, Daniel’s limited success was more a result of the failure of legal representation from the theatre.

The Albertan, 26 March 1914.

Secret Calgary: Kicking Up A Fuss

Watch

In 1914, Charles Daniels entered a Calgary theatre with a paid ticket. He was denied his seat because he was Black. In this little-known civil rights story, Daniels reminds us that history is full of forgotten heroes. Footage from the film Secret Calgary: Kicking Up a Fuss is provided courtesy of TELUS. Originally released in February 2020.

Attempts were also made to exclude Black people from living in certain areas of cities. In 1920, four families moved into the previously all-White Victoria Park area of Calgary. The White families submitted a petition signed by 472 of the district’s 670 households asking the Calgary city council to prevent Black residents from occupying the area or to move them out from that area. Strangely, by way of solution, on 1st May 1920, White residents in Victoria Park were invited to appoint delegates to a conference with representatives of Black individuals against whose invasion they protested.

Hazel Proctor (Ostler) being interviewed by Dr. Jennifer Kelly & Donna Coombs-Montrose, October 2001

Watch

Daughter of an active member of the local Calgary Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, Hazel Proctor (Ostler) was born and schooled in Edmonton, and began her work life there before moving to Calgary. Her father’s roots were in Ohio; her grandmother was part of the Oklahoma trek which settled in Amber Valley…. As leader of the Alberta Association for the Advancement of Colored People (AAACP), she dealt with discrimination and systemic racism faced by Black parents in the public schools, and in using swimming pools, dance halls and other public places. A Community leader and activist, Proctor (Ostler) – who belonged to several women’s organizations – describes the main job opportunities for Black women during the 1950s and 1960s as house cleaning with very low pay.

No. 2 Construction Battalion WWI

It was not easy for young Black men to join the Canadian army during the First World War. When WWI broke out many Black men wanting to join the war effort had difficulty enlisting in the Canadian Expeditionary Forces (CEF) and were met with inconsistent responses from recruitment offices. Some men were able to join individual regiments but, in the eyes of other officers, they were not regarded as suitable soldiers.

During WWI, Bob Jameson and Columbus Bowen from Pine Creek, Alberta (later re-named Amber Valley) joined the segregated No. 2 Construction Battalion based in Nova Scotia. Image courtesy of the City of Edmonton Archives, EA-223-92_141.

Read more at Veterans Affairs Canada: Black Canadians in uniform — a proud tradition.

“Science and public opinion accepted that certain identifiable groups lacked the valour, discipline, and intelligence to fight a modern war. Since those same groups were also subjects of the European overseas empires, prudence warned that a taste of killing white men might serve as appetizer should they be enlisted against a European enemy.”

James W. St. G. Walker, “Race and Recruitment in World War I: Enlistment of Visible Minorities in the Canadian Expeditionary Force,” 1989.

Although the official government position was that the army was not segregated, correspondence between senior officers demonstrates that there was an unwillingness to accept Black recruits. Several officers felt that White recruits would not want to mix with Black recruits.

Across Canada, several young Black men wrote the government asking whether there was a “colour line” in the army. The response was that no such line existed although agents did apply rules strictly. In July 1916, with falling numbers of volunteers and mounting pressure, the situation changed. Following a discussion with the British War Office, Canadian Prime Minister Borden decided “our authorities might be induced to try the experiment of putting Black conscripts into segregated battalions.”

Rev. Geo Washington (identified as Archbishop) who had lived in the United States and relocated to Edmonton to minister to the poor wrote to local Officers and to the Lieutenant Governor R.O. Brett indicating that the local community was fully prepared to fight for King and country. Washington estimated he could gather a large number of Black recruits for the CEF, which was an exaggeration in relation to the size of the communities at that time. His letter indicated the strong desire for some members of the local Black community to fight for Canada and by doing so hopefully gain respect and recognition as full citizens.

After much reluctance and discussion, the No. 2 Construction Battalion, based in Nova Scotia, began to enlist men from all over Canada, including Alberta, on July 5, 1916. In March 1917, the SS Southland left port in Nova Scotia, for the UK with members of the No 2 Construction Battalion on board.

Janet Nettie Ware, daughter of John & Mildred Ware, recalls her brother’s enlistment in the Canadian Expeditionary Forces during WWI:

“Two of my brothers went to World War I – Billy was old enough to go but Arthur wasn’t sixteen years old. Poor grandma; it just broke her heart –Arthur not sixteen years old and going to war. Anyhow, she went to town here in Calgary to try and get him out. The neighbours said “Mrs. Lewis, where’re you going so early in the morning?”

“Well, Arthur went and signed up, and I’m going to see if I can get him out.”

“Mrs. Lewis it’s going to cost you more money than enough and a lot of red tape—and you mightn’t get him out. You might as well turn around and go back home.” She did that and let him go. Both of my brothers came home; they fought in trenches in those times, in World War I.”

The Window of our Memories by Velma Carter & Wanda Leffler Akili (1981).

Guiding questions

- How did things come to be as we see them today?

- Consider your community, your own actions, the media, & Canadian politics. How do you see social exclusion continuing to take place today?

- Have you ever experienced a time in your life where you have been excluded based on the way you look, your gender, sexual preference, or religion?

- How did that make you feel?