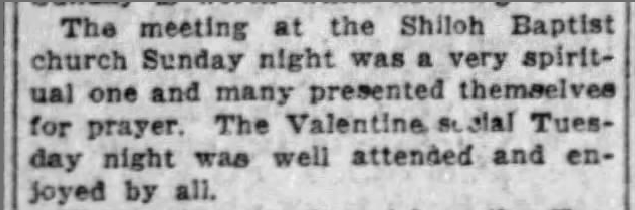

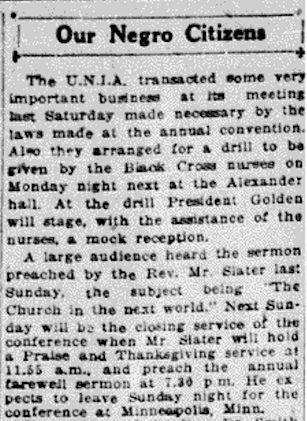

“Our Negro Citizens” (ONC) was a weekly column in the Edmonton Journal and Edmonton Bulletin in the early 1920s. It was written by Reverend George W. Slater Jr., pastor of the Emmanuel African Methodist Episcopal (EAME) church in Edmonton.

The columns were often placed alongside the religion section and other news items. Each issue consists of short descriptions and comments on the everyday comings and goings of a budding Black Canadian community in and around Edmonton.

“The six o’clock tea given by the Deborah Star club in honor of the Mrs. Rev. Slater who will leave in a few days for the States was a very pleasant affair and largely attended. A nice purse was realized by the ladies to assist Mrs. Slater on her trip.”

Edmonton Bulletin, 8 May 1922.

ONC reported social activities such as weddings, church meetings, dining, and entertainment to fundraising, political elections, and lectures given by the people within and outside the community. Although Edmonton was the hub for the ONC column, the comings and goings between the four rural Black communities are also highlighted.

Since both the Edmonton Journal and Edmonton Bulletin were aimed at the majority population of White readers, we can assume that the intended audience of ONC was not just Black Canadians but was also intended to inform White Canadians.

Guiding questions

- The Edmonton Journal and Edmonton Bulletin were both newspapers primarily aimed at White readers. How might this influence the type of news reported by Rev. Slater in the Our Negro Citizens columns?

- How might these columns have influenced White readers?

“The wedding of Mr. William Carroll and Miss Edrena McAdams took place last Sunday at the home of Mrs. John Sales in Strathcona. The Rev. J.S. Strong of A.M.E. church of Calgary officiated. Mrs. Josephine Barzie was the maid of honor and Mr. Thomas Harve was the best man. The bride was very pretty adorned with a cream silk gown trimmed with wide cream silk lace and wide satin ribbon and wore white kid slippers.”

Edmonton Bulletin, 12 December 1921.

“The concert given by the choir of the Emmanuel A.M.E. church at the Albany Avenue Methodist church on the night of Good Friday was indeed a most enjoyable affair. The church was filled with a very responsive audience and every participant in the solos, duetts, quartettes, choruses and recitations aquitted themselves well.”

Edmonton Bulletin, 24 April 1922.

By the late 1930s, economic conditions forced the new pastor, WRT Romain, to move to Junkins where there was a membership of eight and a Sunday school of seventeen pupils. The church buildings had living accommodation at the back for the pastor.

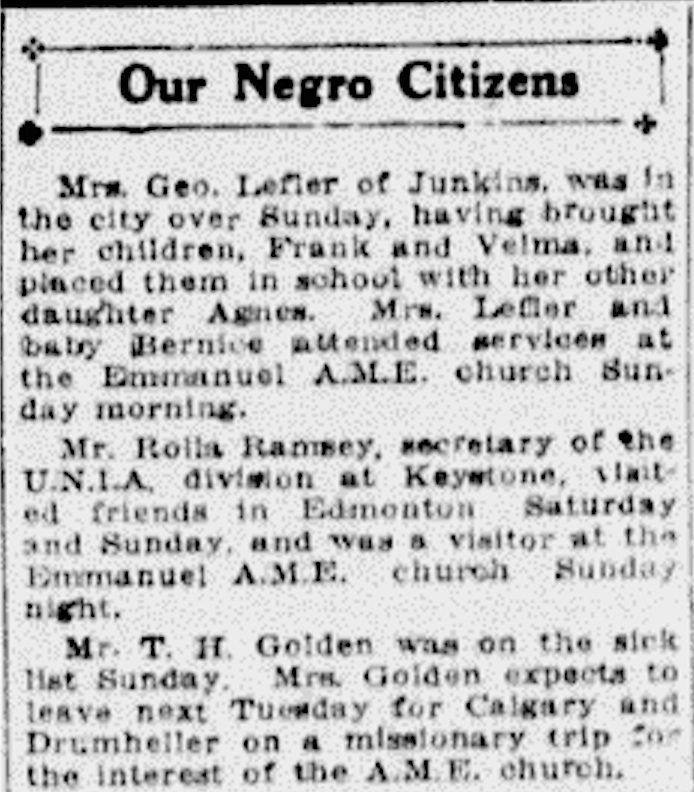

“Mrs. Geo. Lefler of Junkins, was in the city over Sunday, having brought her children, Frank and Velma, and placed them in school with her other daughter Agnes. Mrs. Lefler and baby Bernice attended services at the Emmanuel A.M.E. church Sunday morning.

Mr. Rolla Ramsey, secretary of the U.N.I.A, division at Keystone, visited friends in Edmonton Saturday and Sunday, and was a visitor at the Emmanual A.M.E. church Sunday night.

Mr. T.H. Golden was on the sick list Sunday. Mrs. Golden expects to leave next Tuesday for Calgary and Drumheller on a missionary trip for the interest of the A.M.E. church.”

Edmonton Bulletin, 14 January 1922.

“The meeting at the Shiloh baptist church Sunday night was a very spiritual one and many presented themselves for prayer. The Valentine’s social Tuesday night was well attended and enjoyed by all.”

Edmonton Journal, 18 February 1922.

Much of the literature that discusses this period assumes that city experiences were rife with ongoing daily racism and discrimination that prevented Black citizens from acting on their own behalf. But an examination of the everyday lived experience of city and rural folks through the ONC column illustrates how peoples of African descent, despite racism, were able to live active lives with similar, as well as different, aspirations to those who were racialized as White.

The ONC columns reveal many different social and political activities organized around the Emmanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church some of which gave social and economic solace that would certainly challenge the status quo and give Black Canadians support for dealing with racism as well as other social issues. For Example, Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association had membership in at least three communities and the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union had three groups at one time.

Rev. George W. Slater Jr. used this newspaper column as a way to challenge unequal power relations, reinforce the sense of Black folks as good citizens, and build a sense of community between Edmonton and scattered Black rural communities.

Guiding question

- How might the reporting of everyday life challenge stereotyping and the racialization of Black Edmontonians in the 1920s?

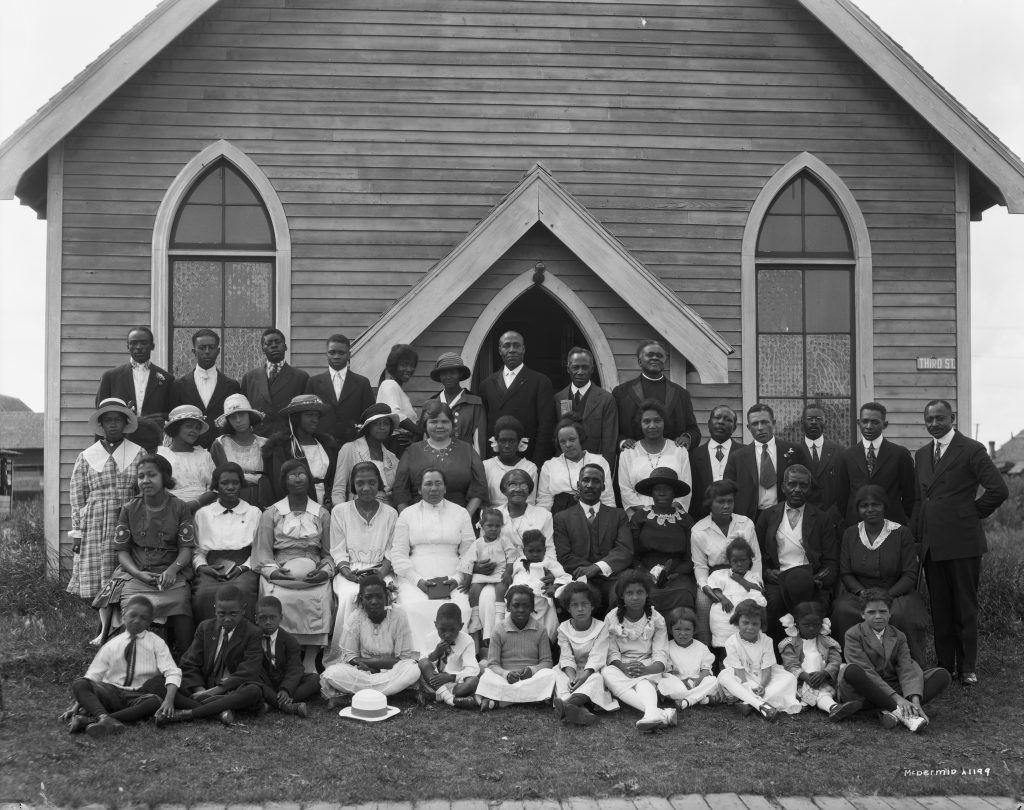

Rev. George W. Slater Jr.: Pastor of Emmanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church

Reverend George W. Slater Jr. was the pastor of the Emmanuel African Methodist Episcopal (EAME) church of Edmonton. Starting in 1921 and continuing through to at least 1924, Rev. George W. Slater Jr. was identified as the compiler of “Our Negro Citizens,” meaning he had some control over which activities were included or excluded. As a member of Emmanuel African Methodist Episcopal, he associated himself with a denomination that was founded on both theological and sociological beliefs. The underlying ideology of Slater’s church rejected the then-popular negative theological interpretations that tended to dehumanize and render people of African descent second-class citizens.

Rev. George W. Slater Jr.: Pastor of Emmanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church

Reverend George W. Slater Jr. was the pastor of the Emmanuel African Methodist Episcopal (EAME) church of Edmonton. Starting in 1921 and continuing through to at least 1924, Rev. George W. Slater Jr. was identified as the compiler of “Our Negro Citizens,” meaning he had some control over which activities were included or excluded. As a member of Emmanuel African Methodist Episcopal, he associated himself with a denomination that was founded on both theological and sociological beliefs. The underlying ideology of Slater’s church rejected the then-popular negative theological interpretations that tended to dehumanize and render people of African descent second-class citizens.

This card shows a photograph of Mr. & Mrs. Slater who were successful at developing the E. A.M.E. church in Edmonton and Junkins.

Image courtesy of the City of Edmonton Archives, MS-386_F2.

While not discussed directly in the everyday comings and goings of the “Our Negro Citizens” columns, some background information on Rev. George W. Slater Jr. is available. He was an American who regarded his position in Edmonton as missionary work, which was regarded as necessary during the early 1920s due to a lack of social services and state responsibility for caring for those in need. His wife, Missouri, adopted the gendered role of helpmate for her husband’s various missionary duties and is often praised in ONC for her singing and administering to the sick. (Cui & Kelly, 2010)

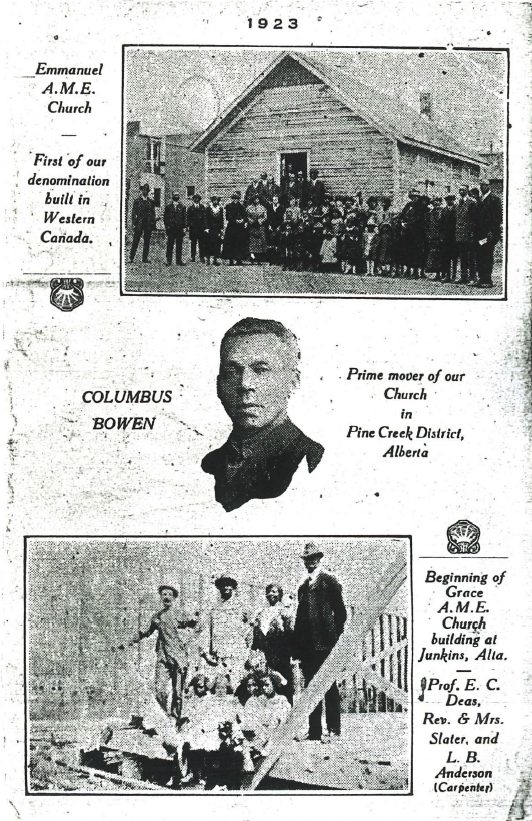

The back sheet of the pamphlet shows the building of the new Grace A.M.E church in Junkins and also gives recognition to the work undertaken by Columbus Bowen in Pine Creek.

Image courtesy of the City of Edmonton Archives, MS-386_F2.

Rev. Slater was educated at the well-known AME Wilberforce University and he had at least two daughters, both of whom lived in Los Angeles with his parents and sister. When reading the column, it is evident that the United States is still an important aspect of the Reverend’s life as he and his wife travel back and forth to the US to visit family or attend various AME conferences.

“[Slater] expects to leave Sunday night for the conference at Minneapolis, Minn.”

Edmonton Bulletin, 8 October 1921.

The US-based African Methodist Episcopal parent church developed from a protest movement against racism, making Rev. Slater’s position within the community both religious and racialized.

In the 1920s, Edmonton had two Black churches: Methodist Emmanuel African Methodist Episcopal and Shiloh Baptist Church. While Rev. George W. Slater Jr. does, to some extent, prioritize and highlight EAME church activities in ONC columns, he also includes Shiloh Baptist Church events. In ONC articles, racialized identities seem to be privileged in relation to religious denomination:

“Last Tuesday night at the Shiloh Baptist church was organized the Douglas Athletic club which proposes to encourage the colored men and women in all sports such as baseball, football, basketball, lawn tennis, croquette and all track work. The club is composed very largely of persons belonging and attending the two churches, Baptist and Methodist.”

Edmonton Journal, 15 April 1922

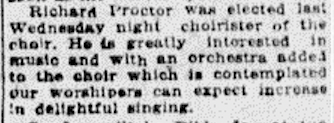

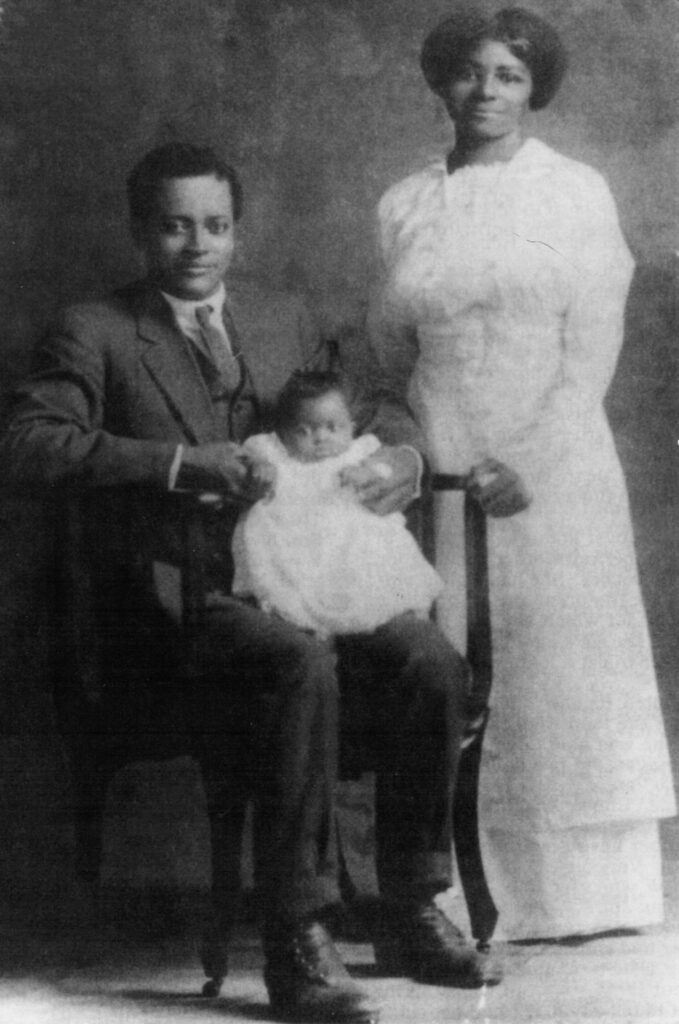

Among the parishioners frequently mentioned were Mr. Richard Proctor and Mrs. Estelle May (Cowan) Proctor.

“Richard Proctor was elected last Wednesday night chorister of the choir. He is greatly interested in music and with an orchestra added to the choir which is contemplated our worshipers can expect increase in delightful singing.”

Edmonton Bulletin, 3 February 1923.

“Much interest is being shown in the Business night to be given at the EAME church on Wednesday night May 10th under the management of Mrs. Proctor and a committee of ladies.”

Edmonton Bulletin, 6 May 1922.

“Mr. Richard Proctor and his partner Mr. Huntingdon has bought out the Globe Express company of which Mr. TH. Golden and Frank Bell were proprietors and with Mr. Bell will conduct that business.”

Edmonton Bulletin, 13 May 1922.

Pictured: Richard Ellis Proctor, his wife Estelle May (Cowan) Proctor and their baby Ruby, circa 1917 in Edmonton, Alberta. Both Richard and Estelle were active members of the EAME church during the time Rev. Slater was pastor of the church.

Image provided by Dr. Jennifer Kelly, courtesy of Judith Maxie.

“The Black Cross Nurses of the CNIA served a very enjoyable tea at the home of Mrs. Richard Proctor’s Tuesday evening.”

Edmonton Bulletin, 5 December 1921.

“Little Ruby Proctor had a very sick spell of croup the first of the week, but is now convalescent.”

18 February 1922.

In the 1930s, Ruby moved with her sisters Pearl and Elnora to Vancouver where they achieved success in music and the arts. Ruby became a pioneering Suzuki piano method teacher in Vancouver while her sister Elnora (aka Eleanor Collins) became one of the first Black artists in North America to host their own national television show, ahead of Nat King Cole.

Ruby Sneed (1917‒1976) – Classical Pianist/Music Educator

This section is courtesy of ©Theresa F. Lewis (née Sneed) 2010.

Canadian-born pianist and music educator Ruby Sneed completed her classical piano training with Jean Coulthard and Jan Cherniavsky in the early 1940s. To secure music teaching credentials, she obtained her ARCT (Associate of the Royal Conservatory of Toronto), receiving the highest marks among all the ARCT students in Western Canada. Shortly thereafter, CBC Radio broadcast one of her recitals.

Ruby Sneed (1917‒1976) – Classical Pianist/Music Educator

This section is courtesy of ©Theresa F. Lewis (née Sneed) 2010.

“If children hear fine music from the day of their birth and learn to play it, they develop sensitivity, discipline and endurance. They get a beautiful heart.”

Shinichi Suzuki

Canadian-born pianist and music educator Ruby Sneed completed her classical piano training with Jean Coulthard and Jan Cherniavsky in the early 1940s. To secure music teaching credentials, she obtained her ARCT (Associate of the Royal Conservatory of Toronto), receiving the highest marks among all the ARCT students in Western Canada. Shortly thereafter, CBC Radio broadcast one of her recitals.

At the beginning of her musical career, Ruby had the singular honour to play for the notable American contralto Marian Anderson. Impressed with Ruby’s talent, Anderson would go on to mentor her. Very few Black women who pursued classical music careers in the early 1900s were taken seriously by the public.

Nonetheless, Ruby was highly motivated and determined to overcome any social barriers that would impede her goals. Studying the careers of successful female North American and international classical musicians helped her craft her own professional path. She was particularly inspired by the careers of Gina Bachauer, Rosina Lhévinne, Leontyne Price, and Lili Kraus.

Ruby’s self-educated parents who, as part of the first migration of Black pioneers from America, emigrated to Canada from Oklahoma in 1909, encouraged their three daughters to pursue formal education and excel at whatever they chose to do. Ruby, the eldest, was a high achiever both academically and musically in her hometown Edmonton, Alberta. Middle child Eleanor Collins excelled at jazz singing and would go on to become the first Black person in North America to have her own television series (Canadian Broadcasting Corporation). Youngest sister Pearl Brown started her career in the business sector, but her love of theatre and music drew her back into the world of the performing arts as an avocation in her later years.

After moving to Vancouver in the late 1930s, Ruby met and married Stanley Sneed, and they had two daughters. Like her mother, Brenda (now deceased) was an accomplished musician. While attending the Juilliard School of Music she studied with Rosina Lhévinne. She pursued a career as a concert pianist under the sponsorship of Baldwin Pianos. In 1984, she moved to Calgary where she was appointed Director of the Early Childhood Music Program at Mount Royal College. Younger daughter Theresa Sneed Lewis studied both piano and violin during her formative years. Theresa currently resides in Calgary, Alberta, where she is the principal of a highly respected fine arts school. She is also a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Toronto.

Beginning in 1948, Ruby focused her career on early childhood music education. Astutely aware of young children’s capabilities, she began teaching piano to eager learners at the Chinese YMCA. Nine years later, she opened her own private studio working with children as young as 3 years old. Over the next 28 years, she would nurture the musical talents of some 75 students each year.

Many of those students would earn scholarships, medals, and first-class honours in local, provincial, and international competitions consistently. Many more would go on to graduate studies and teaching positions at such major music institutes as the Brussels Conservatory, Moscow Conservatory, Paris Conservatory, Juilliard, University of Indiana (Bloomington), UCLA, Aspen Music School, and Banff Arts Centre.

Always an innovator, during this period Ruby was also involved with several projects. In 1963, for example, she wrote the script, “The Promised Land,” for the CBC TV series Heritage.

In 1972, a grant from the Community Music School of Greater Vancouver (a.k.a. Vancouver Academy of Music) enabled Ruby to travel to Japan where she observed firsthand the internationally renowned Suzuki Talent Education Method for piano students. Impressed with the practicability and effectiveness of the Suzuki philosophy, she organized the first Canadian Suzuki piano program at the CMSGV. It commenced with an enthusiastic enrollment of some 50 children, ages 3 to 5. The program was so successful she returned to Tokyo in 1974 with two of her students who would perform in several Japanese recitals.

Word spread quickly in Western Canada about Ruby’s adaptation and development of the Suzuki philosophy of teaching. Before long she was a sought-after lecturer and teacher of master classes at institutions in cities throughout North America and abroad. Guest appearances on educational television in Canada and the United States followed, until her untimely death in 1976.

Ruby’s commitment to music education was not only for the promotion of excellence in piano performance it was also her way “to contribute to making this world a better place” (1965: Ruby Sneed Master Class).

Shirley Oliver

On January 28, 1922, ONC reported that “Mr. Shirley Oliver was chosen to succeed Mr. Ira Day as trustee of the Emmanuel A.M.E. Church. Mr. Day having resigned. Mr. Oliver has purchased a fine moving picture outfit and had gone into that business in the northern part of Alberta.”

In addition to being active in the A.M.E. church, Oliver was a well-recognized pianist who sometimes played with the Graydon Tipps Orchestra. He is pictured on the left of the above photograph.

Guiding question

- Having gone through this exhibit so far, a question to ask oneself is: what group(s) am I a part of and what are its origins? Where does my experience fit within this history?