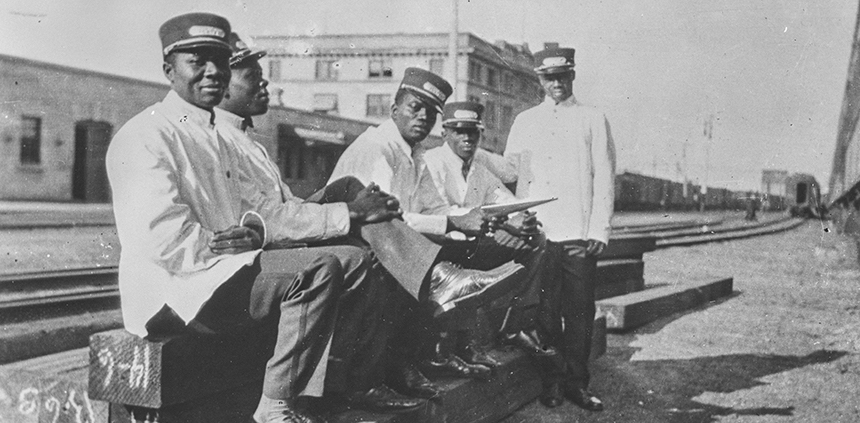

The Canadian National Railway Pullman train bustled through the Rocky Mountains on the way from Vancouver headed for a stop in Alberta. It was loaded with white-only passengers, some traveling with families. Scores of Black/“Negro” servants scurried about, continuing to perform the same services they had throughout the train’s entire journey. They had to be ready – always – to provide the ultimate service from ironing clothes and shining shoes, to carrying passengers’ luggage, from setting up and cleaning sleeping berths, preparing baths, cleaning spittoons, packing suitcases, to tending children, and other personal chores for exclusively white passengers. The trains crisscrossed Canada throughout the early 20th century. In the staff of engineers and conductors, all positions were held by whites – except for the menial job of the porter. In order to make the transportation service profitable, railway companies were dependent on the personalized service provided exclusively by Black porters.

At the time, the train was the major form of transportation across Canada. The train cars afforded the well-to-do lengthy travel in comfort. Inventor George Pullman created the Pullman Sleeping Car which provided this excellent standard of service by porters commonly called ‘Pullman Porters’ — their namelessness an echo of earlier dehumanization during the era of slavery. Their roles and function were deliberately crafted. To remind them of their subservient, ‘invisible’ position, passengers called all porters ‘George’ – coincidentally Pullman’s first name.

In the 1920s, over 20,000 Black men worked as porters for the Pullman train companies. On the trains, the jobs of porters were the only jobs available for men whom the system had deemed unsuitable for any other kind of employment or profession; this one was stamped with second class servitude. Porters tolerated the demeaning racist treatment and offensive behaviour because they relied on these jobs to feed their families. They were considered ‘good’ jobs in Black communities with high unemployment.

Always ready to work, porters had to maintain three places to live: wherever their families were, a small cubicle on the train, and at either end of the train’s route. To facilitate this readiness, Black neighbourhoods began to develop at the train’s final stop. If the train’s run ended in Vancouver, then porters would find a hostel in Hogan’s Alley; if in Montreal, they’d head for Little Burgundy; or to Africville in Halifax. In the following years, systemic racism in housing would impact these communities. Africville (a thriving community of thousands) was completely bulldozed in 1951 to make way for industrial development in Halifax.

At the turn of the 20th century, Canada sought to develop its population in Western Canada, and posted advertisements across the southern United States meant for white interested applicants. Thousands of African-Americans responded to the call and made the trek to the nearest western Canadian border.

The exception to this ‘open’ invitation were the 500 Black porters who arrived in Canada between 1916 and 1919 to work for the Canadian Pacific Railway. Their travel credential was their Pullman Porter identification, which confirmed their singular source of approved employment.

The subtleties of Canada’s racial history were relatively unknown to those fleeing the conditions of racial oppression in the United States. Preferred immigration was reserved for whites from Western Europe and the United States. Black persons held the lowest rung on the ladder.

Other arriving non-whites who expected a Canadian welcome were stopped at borders by the invoking of an Order-in-Council.[1] The Order banned Black persons from entering Canada (initially) for a period of one year. It deemed “the Negro race unsuitable for the climate and requirements of Canada”. Financial resources and supporting skills had to be verified also before entry would be considered.

Following their successful entry to Canada, Black immigrants also found active chapters of the Ku Klux Klan in Alberta’s communities, barriers to obtaining housing, ordinary public services and employment. New arrivals felt very unwelcome. They recognized the familiar stench of racism. The treks arriving from Oklahoma and Tennessee were geographically segregated off to Amber Valley. They were not encouraged to live in suburban or aspiring middle class neighbourhoods.

Employers exploited this situation of cheap, available labour. Unemployed, homeless, destitute men grasped at the chance to be employed. For women, the opportunities for employment were even more restricted, mainly to housekeeping, washing and ironing, and other menial tasks.

Wages in the transportation industry for porters were reported to be $100/month or less. The norm was: ‘if a job paid more than $1, it’s a white man’s job.’ Porters interviewed for ‘The Road Taken”[2] reported poor working conditions, ‘dead end’ positions as porters with no chance of promotion as the position of train conductor was reserved for whites only. Black porters worked 21-hour days. They endured sleep-deprivation, long periods away from their families, and were dependent on the charity (tips) of passengers to earn any income. The service provided by the porters was expected to be exceptional, constantly ensuring that passengers were satisfied. One porter reported that he felt humiliated, third class, the consummate invisible man. The train companies set rigid standards and rules with hundreds of grounds for dismissal, which the Canadian train industry adopted.

Hazel Proctor, daughter of a sleeping car porter, describes the hardships of her dad’s job on their Calgary-based family.[3] She relayed,

“As a sleeping car porter, he would put up and take down the beds and service the customers on the sleeping cars. So, it was a tough job for him…Any time he would lay over in Calgary, my mother and I would walk up to the train station and help him do his berths, help him take them down, make the beds and so on. That would sometimes be the only time we’d see him. I guess he would give mom his check…. [As] the oldest, I’d go with mom so I was part of my dad and what he was doing. I knew what it was to make down a berth and so on. I don’t know about the others, that was what my mom and I did, because he wouldn’t be able to leave the station if he was going straight through. He wouldn’t be able to leave and come to the house… his route on the trains [included] Calgary, Winnipeg, Montreal… But I didn’t know till later on that it was kind of hard for her….with 5 kids, and later on there was 7 of us. The railway was very close… Some porters joined the AAACP – Alberta Association for the Advancement of Coloured People.” This organization, affiliated with the NAACP, advocated against racial discrimination and segregation in housing and public places.

Proctor’s Dad, Bert, later became the local president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters.

The existing industry union – Canadian Brotherhood of Railway, Transport and General Workers Union – excluded Black workers from its membership. In 1925, porters intensified the arduous task of union organizing. A. Philip Randolph was a rising young African American Socialist who was drawn to the plight of the porters. Historically, he is known as Chairman of the (now famous) 1963 March on Washington at which Rev. Martin Luther King made his famous “I have a Dream” Speech. Randolph would use his access to media sources to highlight the working conditions of Black porters and the porters hired Randolph to organize their union. He was not employed by any of the transportation giants, so his employment could not be threatened, neither could he be bribed or intimidated.

Organizing in the United States persisted until 1937 when the first Black labour union – the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters- won their first collective agreement and their union charter. Encouraged by this development, porters in Canada tried repeatedly to form a Canadian affiliation of the Brotherhood. Pullman’s agents and the Canadian rail giants crushed their efforts at every turn. Porters who expressed any interest in the “u” word were immediately fired. The Canadian government replenished the train pool annually with 100 British subjects from the Caribbean. Many of them carried qualifications in different skills, but in the same non-union environment they suffered the same fate of poor working conditions, low wages, lack of any promotional opportunities, and an expectation that they would also do the conductor’s job if asked, free of charge.

Organizing drives continued relentlessly across Canada. In 1946, the Brotherhood organized the porters of the Canadian Pacific and the Northern Alberta Railway, and the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP) became the first trade union in Canada organized by and for African-Canadians.

BSCP immediately set about seeking better wages and working conditions for union members. For the first time, porters had job security, reduced work hours, increased wages and in a short time – dignity. The dehumanizing label of ‘George’ was kicked off the train. Porters carried metal name tags on their chests identifying their official names. Later on, each train compartment also carried their name plates at either end. George was outlawed! One porter reporting his experience with an obnoxious passenger, informed the passenger: “I will serve you, but I will not allow you to buy my integrity for $10.” Their progressive BSCP union also pressured federal and provincial governments to create legislation prohibiting discrimination in employment and housing. A large contingent of BSCP also joined the 1963 March on Washington to add their voices to the call for national unity and an end to racial segregation. In 1964, African-Canadian porters were finally employed in other promotion-stream positions at the Canadian National Railway and Canadian Pacific Railway. They could now support the higher education aspirations of their children and better lives for their families.

Driven by their social consciousness, BSCP continued their campaigns against Discrimination and Unfair Labour Practices, impacting major changes in the existing legislation. Their gains lifted the social and economic standards of African Canadians, addressed disparity in gender employment, and the creation of higher upward mobility in their communities. Because of their consistent agenda of advocacy for all, the BSCP is also credited with breaking down some traditional barriers of racism and contributing to the building of a multicultural Canada.

Donna Coombs-Montrose © 2021

[1] https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/order-in-council-pc-1911-1324-the-proposed-ban-on-black-immigration-to-canada.

[2] “The Road Taken, ”Selwyn Jacob, 1998. Selwyn Enterprises/National Film Board.

[3] Albertalabourhistory.ca/hazelproctor.