While life during this period was vibrant it must also be recognized that stereotyping by mainstream society was apparent and affected levels of expectations, as well as the employment prospects, of many of these Black citizens. The ONC column took a strong stance on issues of racism and social exclusion regarded as “drawing the colour line.”

In some ways, the “Our Negro Citizen” columns could easily be viewed as the trivial comings and goings of a specific social group striving for racial uplift and middle-class status. However, a deeper analysis allows us to see a value in exploring further the everyday lived experiences of these pioneers.

Edmonton Journal, 18 February 1922.

We can link specific instances of comings and goings within the communities to wider issues of race and racialization as well as other social issues taking place on a national and international level.

“The colored people of Edmonton rejoiced to know that their honored fellow citizen, the Hon. Charles Stewart, displayed the true Canadian spirit of justice and fair play when he refused to send Matthew Bullock back to North Carolina, U.S.A., where colored people are lynched for almost tiring cause. This action of the honorable minister of the interior was in strict keeping with the attitude of the Canadian government from the old American slavery days when Canada became a safe asylum for the fleeing slave by way of the Underground Rail- road.”

Edmonton Journal, 4 February 1922.

Woman’s Christian Temperance Union

The Woman’s Christian Temperance Union was a temperance organization against alcohol and how it could damage a family, especially husbands. In Edmonton, a group of Black women organized several Woman’s Christian Temperance Unions, including the Phylis Wheatley group.

“In 1932 they reported holding fourteen regular meetings, three special and one parlor meeting. Members of the union canvassed the district during the referendum campaign, held a prohibition concert, put on a drive for new members and have 18 paid up members. Observed Mothers’ day, held a Frances Willard memorial meeting, gave a drama and bazaar from which we realized $129.59, most of which has been spent. We found a home for a small girl who could not otherwise get to school, gave a free Xmas social to orphan children. We mother a L.T.L. of 12 members. Two of our members were part of a committee to wait upon city council to protest against high rental taxes.”

Women’s Christian Temperance Union Annual Convention Report, 1921.

Negro Political Association (NPA)

“The object of the association is as follows: to study political principles and tenets of political parties, legislative measures proposed by legislative bodies, and all political propositions as they affect the welfare of the race. It is not the purpose of this organization to endorse any measure or men, but rather to study and give correct information as to reports, studying treatises, or assembling the colored citizens to listen to representative exponents of various theories and propositions. Also to get the people to become voting citizens.”

22 September 1921.

“The Negro Political Association of Alberta wish to inform the different political parties that we will not endorse any until we have heard all the candidates of the different parties. Then that party that sets forth in their platform the true principles of democracy and the protection of their citizens and country, regardless of race, creed, or color, without discrimination and we are sure these candidates are not camouflaging, then that party we will endorse and give our hearty support to at the polls and live up to our obligation in every respect.”

Edmonton Journal, 22 October 1921.

These reports allow us to rethink the stereotype of Black Canadians in 1920s Alberta as consistently passive victims of racial discrimination, fully segregated from mainstream society. Instead, we find politically and socially engaged citizens.

Incidents or attempts at continuing social exclusion were also well-reported in the Our Negro Citizens column.

Lulu Anderson

In 1922 Lulu Anderson (a member of the E.A.M.E. church), sued the Metropolitan Theatre in Edmonton after being denied entry to watch a film. After a six-month trial, the court ruled in favour of the theatre, stating that they had the right to deny admission to any person if they refunded the cost of the ticket. Although Lulu was unsuccessful in getting justice, she was among the many Black folks who used various means, including the courts, to assert their humanity and resist second-class citizenship in Canada.

Explore more of Lulu’s story here, “Finding Lulu” One Man’s Quest to Find Himself in his own City” by Bashir Mohamed, The Yards 2018.

Bashir Mohamed

Watch

A short interview with Bashir Mohamed about the history & significance of Lulu Anderson. Recorded on 5 August 2021. Interview conducted by Christina Hardie as part of the “And Still We Rise”: A Black Presence in Alberta virtual exhibit hosted by the Edmonton City as Museum Project, based on research by Dr. Jennifer Kelly.

Another example of an attempt at social exclusion was reported in the Edmonton Journal in April 1924.

According to the lurid newspaper details, the accused, Mr. Walker a Black parent, was upset that Mr. Wallace, a teacher, refused to admit another of his children into the local school at Campsie.

Edmonton Journal, 5 April 1924.

Deborah Beaver & the Campsie School

Watch

A short interview with Deborah Beaver about the school in Campsie, Alberta. Recorded on 27 July 2021. Interview conducted by Christina Hardie as part of the “And Still We Rise”: A Black Presence in Alberta virtual exhibit hosted by the Edmonton City as Museum Project, based on research by Dr. Jennifer Kelly.

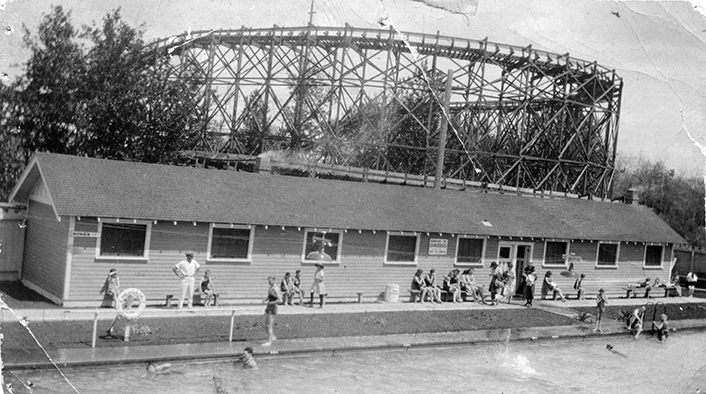

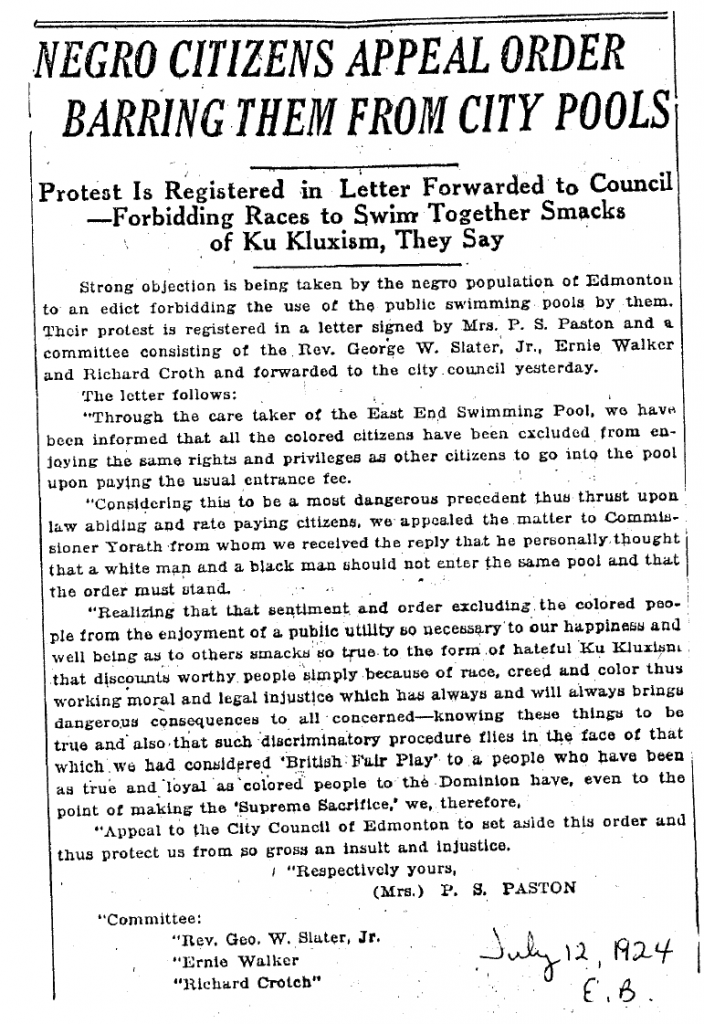

Similar events of social exclusion also took place in Edmonton. In July 1924, an attempt was made to exclude Black citizens from two new swimming pools in Borden and Oliver as well as the older Queen Elizabeth pool.

Rev. Slater, Ernie Walker, and Richard Crotch wrote a letter of appeal to Edmonton’s City Council to set aside this order and protect them from “so gross an insult and injustice.”

“Strong objection is being taken by the negro population of Edmonton to an edict forbidding the use of the public swimming pools by them. Their protest is registered in a letter signed by Mrs. P.S. Paston [sic] and a committee consisting of the Rev. George W. Slater Jr., Ernie Walker and Richard Crotch and forwarded to the city council yesterday.”

Edmonton Bulletin, July 12, 1924.

Guiding questions

- Take a closer look at the newspaper article above.

- What words or phrases stand out to you?

- What words or phrases show the agency of the Black Edmontonians involved?

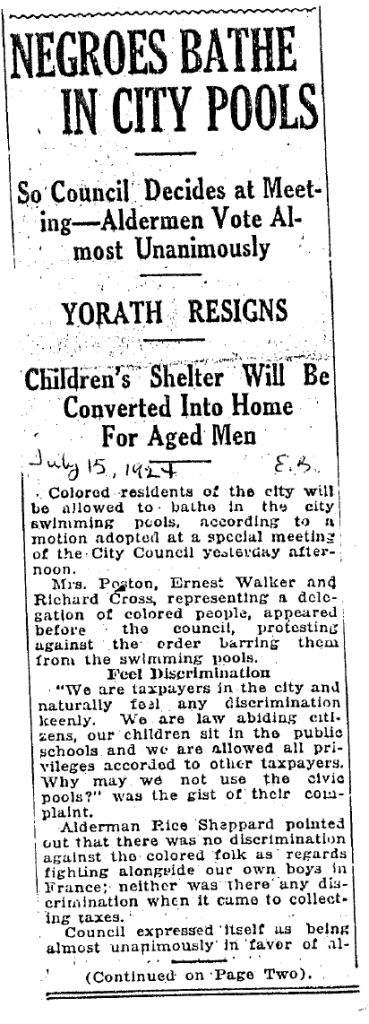

Three days later, through the advocacy of the committee named above, the Edmonton Bulletin reported that City Council voted “almost unanimously in favor of allowing [Edmonton’s Black citizens] full privileges of the pools.”

Edmonton Bulletin, 15 July 1924. Image courtesy of the City of Edmonton Archives.

Black Albertans also faced social exclusion in employment. Restricted employment opportunities and economic racism meant that “in Calgary during the 1920s and 1930s the job of porter was virtually the only one open to [B]lacks.” (“Urban Blacks in Alberta,” Palmer and Palmer, 1981.)

Who were the Porters?

Check out the ECAMP story “The Porter: Building a Better Canada for All” by Donna Coombs-Montrose

The Canadian Brotherhood of Railway Employees and Other Transport Workers union negotiated a two-tiered deal with the CNR railway company. According to the union agreement with the company, there were two groups for seniority purposes. Group I contained a variety of employees such as dining car employees and sleeping-car conductors. Group II were primarily Black sleeping car porters.

Black Porters employed by the Canadian Pacific Railways, 1920s. Image courtesy of the Provincial Archives of Alberta, A9167.

Guiding question

- What kind of work does a porter do?

Urban Black peoples in Alberta during the 1920s are often depicted solely as victims of racial discrimination; little is recorded about their lives as active community citizens. However, according to the ONC, there was also a group of entrepreneurs in Edmonton who were not entirely dependent upon a Black clientele.

On March 28th, 1922, Rev. Slater wrote in an ONC column: “we are glad to see more of our people going into business.” He continually praised the entrepreneurial skills of Mrs. Richard Proctor who opened her own needlework shop, Mrs. Anna Bell who had a dressmaking store, and Mrs. Russell and Mrs. McCathrone who owned a hand laundry.

With the coming of economic depression in the 1930s, we see a movement of people from rural areas into cities or towns in Alberta and British Columbia. Some families went back to the United States although not necessarily Oklahoma. The second generation of Black citizens began to attend school and to look for work.

Education available varied from one community to another and those who attended school in Amber Valley had Black teachers. Black teachers born in the communities included Jesse Jones, Agnes Leffler, Gwen Hooks, Ruby Bransford and others. Representation through minstrelsy depictions continued to be common from earlier eras and, for some students, it was evident in classroom storybooks.

In terms of employment, a number of the men in town had experiences working for the railway, whether part-time or full-time, with varying jobs as cooks or working in the roundhouse. In the 1940s, some of these men would go on to become active in the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. Domestic work was available for women.

Watch

Gwen Hooks, whose parents were pioneers in Keystone moved, when young, to the primarily White community of Radway. She recalls her experiences of schooling and later teacher education at Normal school.

Guiding question

- Having gone through this exhibit so far, a question to ask oneself is: have things gotten better regarding racism against & the stereotyping of Black Albertans? Have things gotten worse?