Beginning in 1939, American A. Philip Randolph visited Canada to assist with organizing an International section of the U.S.-based Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP). The catalyst for this separate organization of workers was the racism that employees of African descent faced on the railway. Black porters faced racism not just from their employers (such as the Canadian Pacific Railway, Canadian National Railway, and Northern Alberta Railway) but also from the Canadian Brotherhood of Railway Employees and Other Transport Workers (CBREOTW) union who had negotiated a racialized two-tier union agreement with CNR in 1927.

Who were Sleeping Car Porters?

The concentration of sleeping car porters in a racialized enclave and their resistance to racism in their workplace through organized labour during the 1940s onwards provided the base for developing a political consciousness around broader human rights issues. Sleeping Car Porters can be regarded as stretching the boundaries of human rights for all traditionally marginalized Canadians.

For further reading, check out ECAMP story “The Porter: Building a Better Canada for All” by Donna Coombs-Montrose

After an ideological struggle and meetings held in secret, an agreement was finally signed with the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) in 1945. Present at the final signing of the agreement between the BSCP and CPR management was P.T. Clay who became President of the Calgary Division of the BSCP. An agreement between the Northern Alberta Railway and the BSCP was signed in January 1946 and became effective on August 17, 1946, in Edmonton.

Members of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and Women’s Auxiliary, with their families, circa 1941-42. Image courtesy of Glenbow Archives, Archives and Special Collections, University of Calgary, PA-3439-6.

Back row, L-R: P.T. Clay, Wilbur Milton, Jeff Bowen, Willis Richardson, ‘Doomy’ Hicks, Embert ‘Amos’ States, Melvin Crump. Middle row, L-R: Peaches Coleman, Willa ‘Gotchie’ Sneed, Louella Bellamy, Ethel Kay, Alex Kay, Rachel Walton, Charlie Walton. Front row, L-R: Roy Williams (holding Judy Williams), Odelle Holmes, Mr. Blanchette, Helen Braithwaite, Cordie Williams.

Two years after the signing of the official agreement with CPR, the Calgary Division organized elections for new officers. Brother Odell Holmes ushered in as President, Brother Alex Kay as 1st Vice President, Brother Coleman as 2nd Vice President and Brother Roy Williams was re-elected as Secretary-Treasurer. Both Odell Holmes and Roy Williams would remain as Chair and Secretary-Treasurer until the Calgary Division of the BSCP was closed.

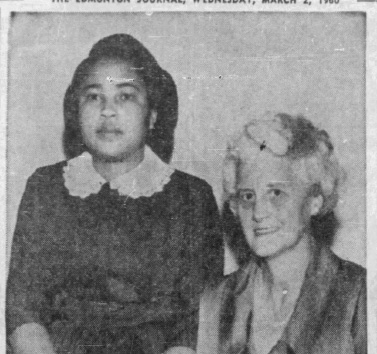

The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters was keen to promote equity and support educational achievements within the community. Among those achieving high honours was Violet King, a descendant of the early Black pioneers who settled in Keystone (Breton).

Following graduation from the University of Alberta in 1953, Violet King became the first Black woman to go to the legal bar in Canada and the second woman in Alberta.

In this photograph, we see her receiving a gift from A. Philip Randolph, President of the International Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. Also present are Bennie Smith and Roy Williams.

Image courtesy of Glenbow Archives, Archives and Special Collections, University of Calgary, NA 56000-7757A.

The BSCP was for more than just wage bargaining. In the late 1940s, A. Philip Randolph visited Alberta and encouraged the development of the Canadian Society for the Advancement of Colored People. In extending the terms and conditions of work, the BSCP fought for improved human and civil rights of all traditionally marginalized Canadians. As members of the Calgary Labour Council, the BSCP advocated for the adoption of the Fair Employment Practices Act and Fair Accommodation Practices Act in Alberta.

One of the main platforms for the Alberta AACP was the issue of discrimination in both employment and housing. Dick Bellamy, a former sleeping car porter, who was active in the formation of the Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (AACP) in the early 1950s, suggested,

“the object of this organization shall be the betterment of colored people, to seek equality as Canadian citizens and the promotion of participation in all social and civic activities.”

Unionization with the BSCP meant, as one Alberta based sleeping-car porter remembered,

“In 1945, our standard of living was raised because we were getting more money; our children were able to at least finish high school and the odd one had a chance to attend one of the leading universities.”

Guiding questions

- Who were Sleep Car Porters? What kind of work did they do on the railway?

- Why do you think Black people were exclusively hired to work as porters?