Newspapers frequently reported negatively on the arrivals of Black immigrants from the United States, including the Edmonton Bulletin, Edmonton Journal, and Calgary Eye Opener. The first group of Black folks to arrive were noted rather disparagingly by one newspaper, “It was in 1908 that the first party arrived from the cotton fields of Oklahoma and settled along the Grand Trunk Pacific, the largest settlement being at Chip Lake.”

Newspapers are useful tools for understanding how Black immigration occurred and the negative attitudes of White Canadians towards the newcomers. Articles highlighting concerns about Black immigration appeared in several major newspapers between 1908 and 1920.

What is Racialization?

Racialization is a term that recognizes race as socially-constructed rather than a purely biological phenomenon. Its use places an emphasis on the active construction of race and the how of racism.

Watch

A short interview with Dr. Jennifer Kelly (Professor Emeritus, University of Alberta), lead researcher and exhibit curator for “And Still We Rise”: A Black Presence in Alberta, discussing racialization in Canadian history.

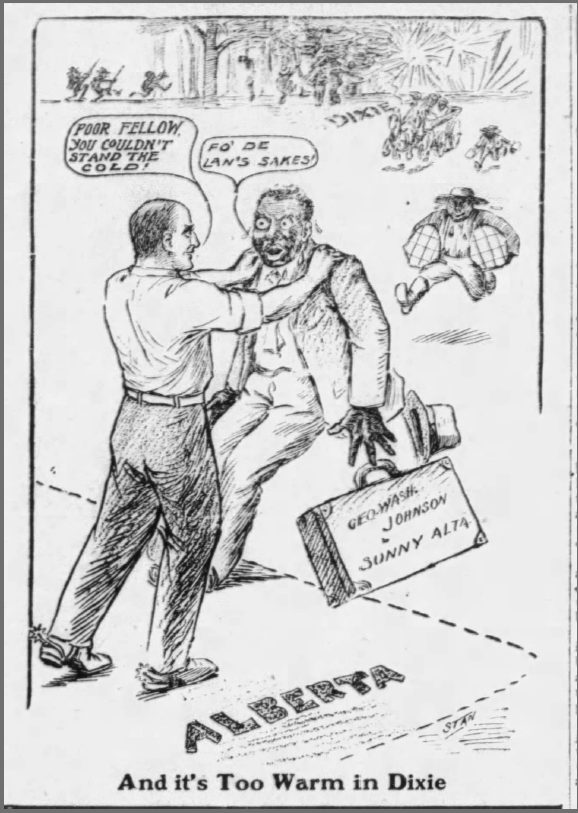

An Edmonton Journal cartoon illustrates anti-immigration sentiments that were expressed by immigration officials and some Edmonton residents. The cartoon portrays Canadian ambivalence towards Black immigration.

The White male in the picture does not directly identify race as a reason for exclusion but instead states that the cold climate is a cause for exclusion from Alberta. Inability to survive in a cold climate was one of several excuses used by immigration authorities to exclude people of African descent. Of course, they chose to ignore the fact that Matthew Henson, a Black man, had reached the geographic North Pole in 1909.

Edmonton Journal, 5 May 1911.

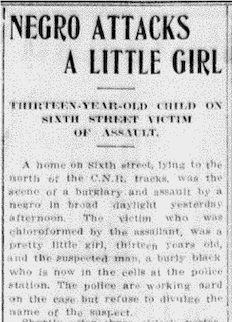

Prairie newspapers were active in perpetuating stereotypes and negative representations of Black Canadians. For example, an isolated incident would be immediately linked to the Black community as a whole and, consequently, negatively impacted all Black pioneers.

One such case happened in Edmonton on April 4, 1911, where, as it turned out, a White girl fabricated a story of an attack by a Black man. This news of the supposed attack spread quickly as prominent newspapers immediately linked Black settlers as a whole with the incident.

“Negro Attacks a Little Girl,” The Edmonton Bulletin, 5 April 1911.

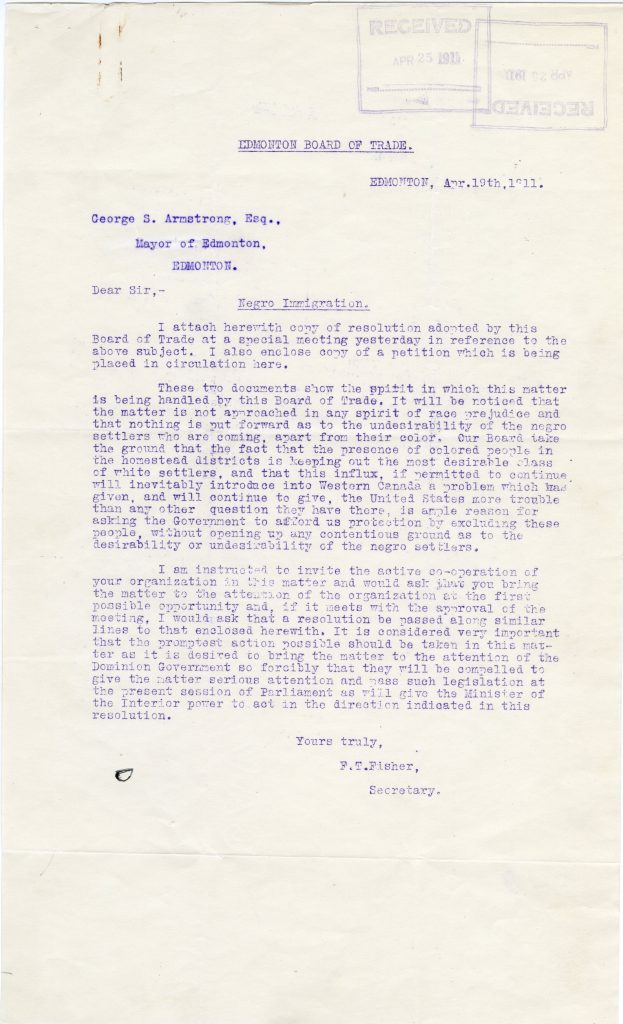

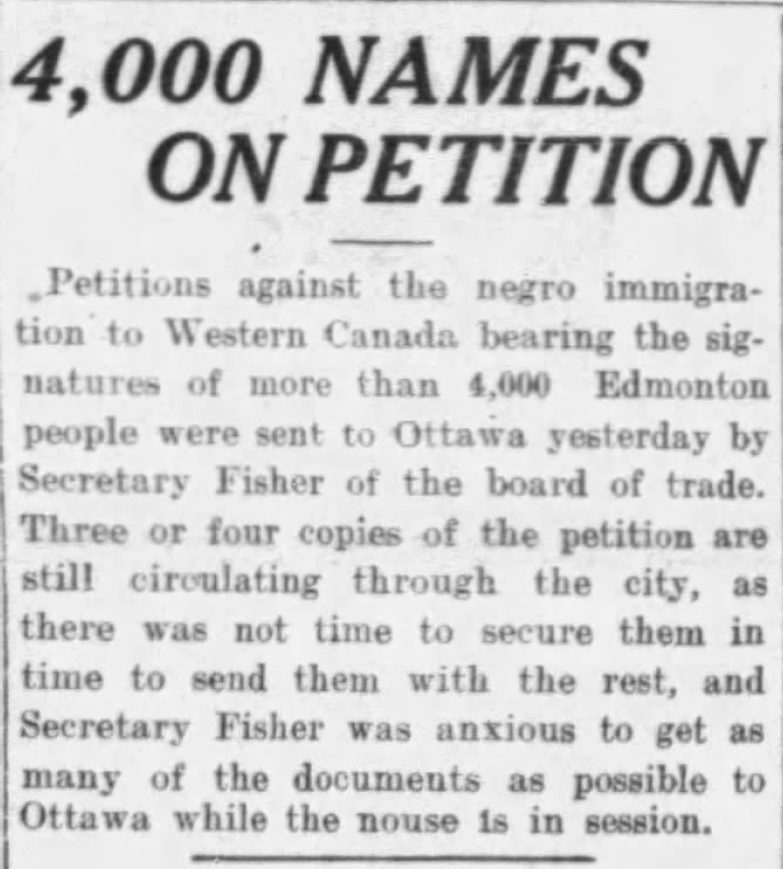

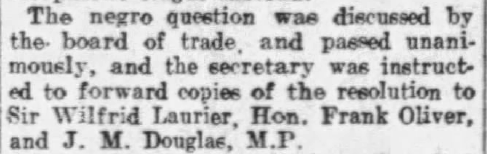

References to “The Black Peril” became a catalyst for agitation against Black immigration to Alberta and provided an underlying logic for a resolution and petition campaign by the Edmonton Board of Trade. While this incident indicates the foregrounding of the age-old sexual mythology that Black men are a menace to White women, it also illustrates the role that newspapers played in depicting Black Canadian men as violent and dangerous. The Edmonton Board of Trade’s petition was distributed to Union Bank, Windsor Hotel, King Edward Hotel, Merchants Bank, and Western Realty Co.

Edmonton City Council along with several other organizations and Boards of Trade gave support for the resolution. The Regina Board of Trade refused to endorse the resolution.

Image text: “Our Board take the ground that the fact that the presence of colored people in the homestead districts is keeping out the most desirable class of white settlers, and that this influx, if permitted to continue, will inevitably introduce into Western Canada a problem which was given, and will continue to give, the United States more trouble than any other question they have there, is ample reason for asking the Government to afford us protection by excluding these people, without opening up any contentious ground as to the desirability or undesirability of the negro settlers.”

Alongside the public outcry in Alberta, the Canadian government increased its use of “unofficial” ways to prevent further Black immigration. Immigration agents tried not to forward information on Canada to Black folks. Senior agents from Canada sought out religious leaders from within U.S. Black communities to campaign against immigration to the Prairies. Cold climate and lack of familiar foods were often cited as reasons for not migrating to Canada.

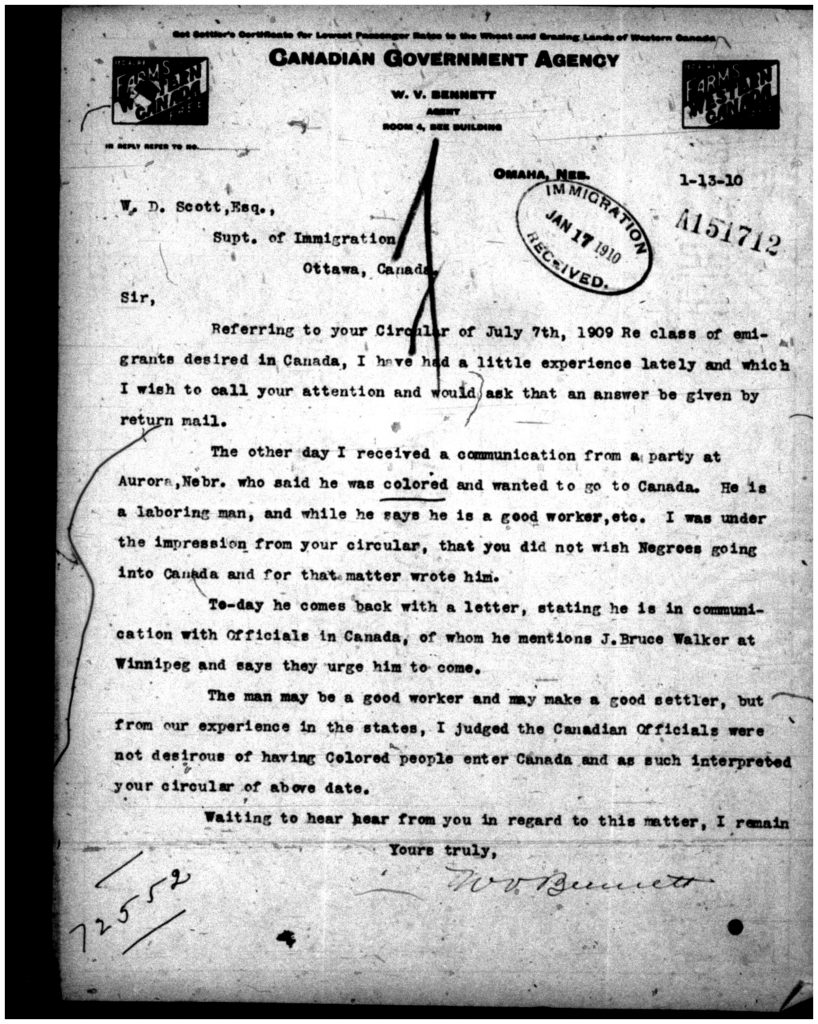

A letter to the Superintendent of Immigration received January 1910 from W.V. Bennett, an agent with the Canadian Government Agency stationed in Omaha, Nebraska, highlights the unofficial policy of not encouraging Black immigration. It reads, in part:

“The other day I received communication from a party at Aurora, Nebr, who said he was colored and wanted to go to Canada. He is a laboring man, and while he says he is a good worker, etc. I was under the impression from your circular, that you did not wish Negroes going into Canada and for that matter wrote him.”

Often, Canadian Government agent J.S. Crawford would seek advice as to the colour of immigrants to decide if they were suitable or not. He wrote from Kansas City, Missouri, to the postmaster in Keystone, Oklahoma:

“Dear Sir: Will you kindly advise me if C.C. Harris is a white or colored man and oblige.”

(November 11, 1910)

The archival document indicates that Postmaster S.R. Morris responded with racial pejorative scrawled across the letter, indicating the applicant was Black.

In a move aimed at those racialized as non-White, the Canadian government adopted Section 38c of the 1910 Immigration Act which allowed the Minister of Immigration to prohibit

“immigration belonging to any race deemed unsuited to the climate or requirements of Canada, or immigrants of any specified class, occupation or character.”

In response to the pressure against immigration the Laurier government also developed an Order in Council (a Cabinet document) in May 1911, which stated that:

“For a period of one year from and after the date hereof the landing in Canada shall be and the same is prohibited of any immigrants belonging to the Negro race, which race is deemed unsuitable to the climate and requirements of Canada.”

Dated 11 August and rescinded in October 1911. Library and Archives Canada, C-117932.

However, this Order was rescinded.

Guiding questions

- Ask yourself the following:

- How should we judge each other’s actions, both in the past and in present day?

- What debt does my group owe others and/or others owe to me?

While concerns about the immigration of peoples of African descent was a common occurrence in many prairie newspapers not everyone was against Black immigration. One of the few favourable newspaper accounts of Black immigration to Canada ran in the Manitoba Free Press on March 25, 1911:

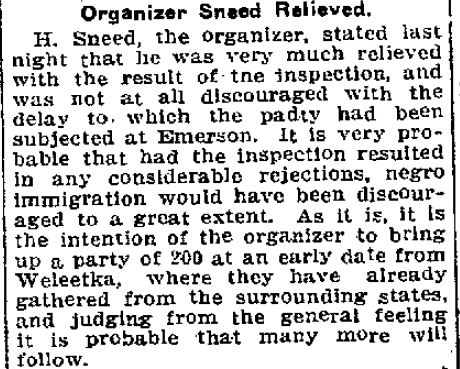

“The movement really started last January when a party of 60 crossed the border line and proceeded to Edmonton, Alberta, where they disembarked from the train, trekking north and taking up homesteads at a place now known as Murphy’s settlement. Sneed, an Oklahoma man of considerable executive ability and comfortable means, made a trip to the country last August and from the favorable reports received from the people and from personal observation of the land, he determined to gather many of his people from the various States of the South and to bring them to the free homesteads of the Canadian northwest.”

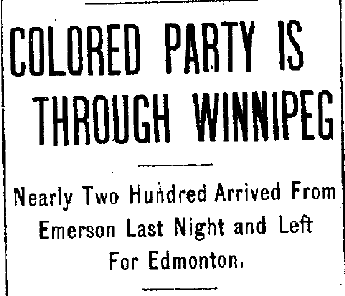

Parson Henry Sneed from Clearview, Oklahoma, led the second party of Black folks arriving from the United States. After crossing the border in Manitoba, their destination was Edmonton.

“Colored Party is Through Winnipeg,” Manitoba Free Press, 24 March 1911.

Historians have speculated that Sneed came to Alberta before 1910 and then returned to the United States to tell friends and family about the Canadian West.

Sneed, along with Murphy and Nimrod Toles, led a party of Black immigrants to an area north of Edmonton near Athabasca Landing in 1910.

“Colored Party is Through Winnipeg,” Manitoba Free Press, 24 March 1911.

Gender, Representation & Immigration

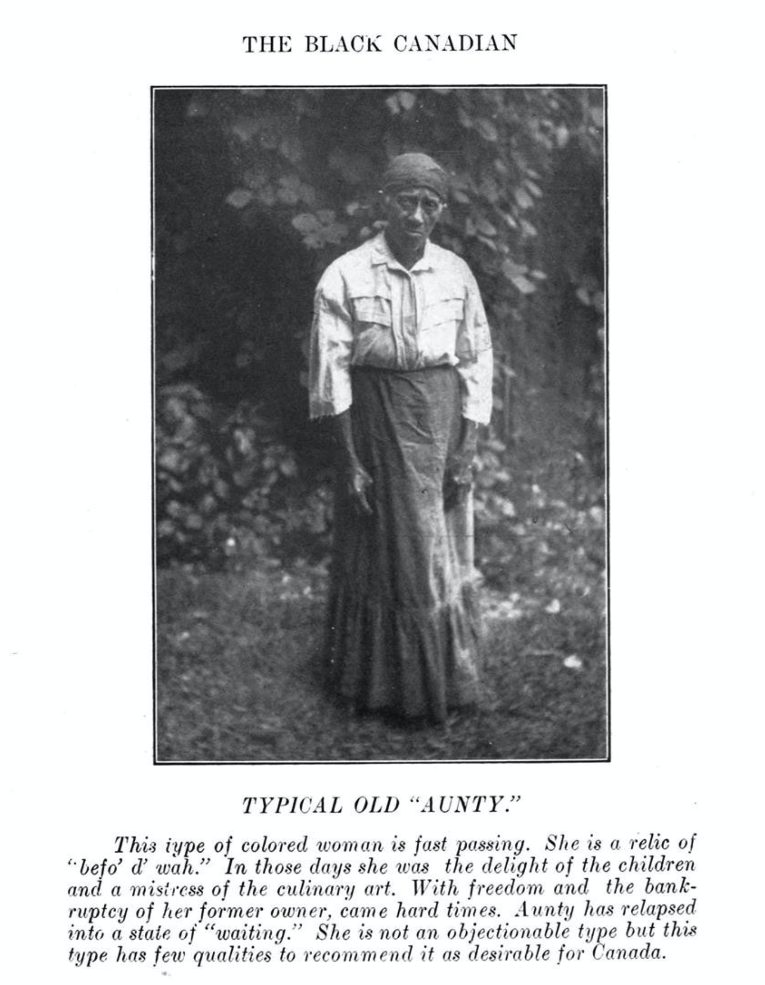

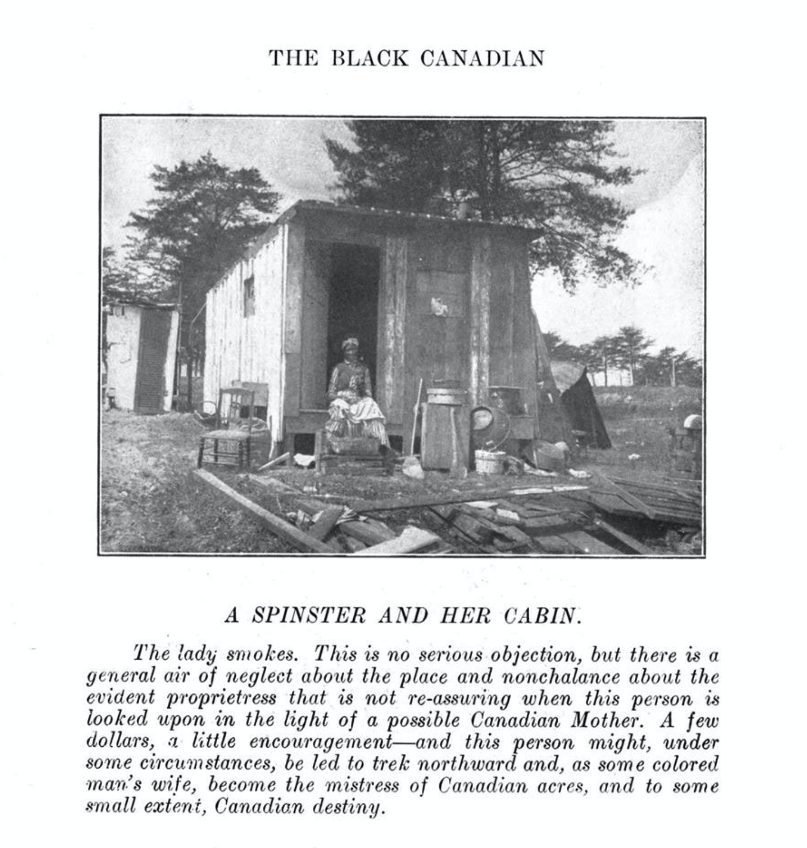

There is a lack of discussion among historians about how Black women were regarded in the broader debate on immigration into Alberta. One useful source for understanding how Black women were regarded is a seminal article entitled “The Black Canadian” published in 1911 in Macleans Magazine.

Gender, Representation & Immigration

There is a lack of discussion among historians about how Black women were regarded in the broader debate on immigration into Alberta. One useful source for understanding how Black women were regarded is a seminal article entitled “The Black Canadian” published in 1911 in Macleans Magazine.

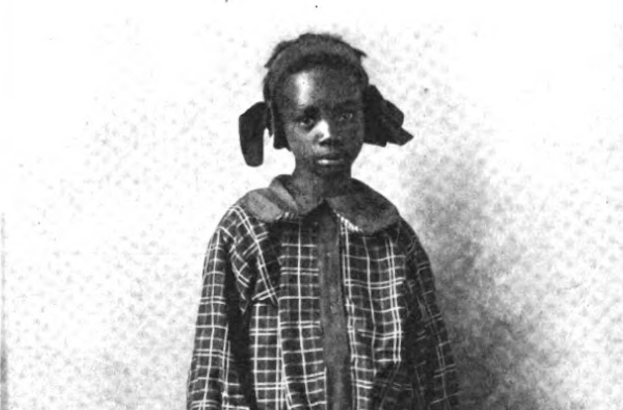

The author Britton Cooke uses photographs and text such as “Typical Aunty” to represent Black women as deficient in their housekeeping skills and thus not good homemakers.

“TYPICAL OLD “AUNTY”

This type of coloured woman is fast passing. She is a relic of “befo’ d’ wah.” In those days she was the delight of the children and a mistress of the culinary art. With freedom and the bankruptcy of her former owner, came hard times. Aunty has relapsed into a state of “waiting.” She is not an objectionable type but this type has few qualities to recommend it as desirable for Canada.”

Maclean’s Magazine, “The Black Canadian- His Place in Canada; His Record: Do We Want Him?” November 1911, page 7.

By highlighting the feminized domain of the home as in constant disarray the author of “The Black Canadian” links the supposed deficit homemaking skills of Black women to broader debates about their unsuitability as Canadians.

“A SPINSTER AND HER CABIN.

The lady smokes. This is no serious objection, but there is a general air of neglect about the place and nonchalance about the evident proprietress that is not re-assuring when this person is looked upon in the light of a possible Canadian Mother. A few dollars, a little encouragement- and this person might, under some circumstances, be led to a trek northward and, as some colored man’s wife, become the mistress of Canadian acres, and to some small extent, Canadian destiny.”

Maclean’s Magazine, “The Black Canadian- His Place in Canada; His Record: Do We Want Him?” November 1911, page 5.

Guiding question

- In these two images taken from MacLean’s Magazine, how are the women pictured being racialized by the author? Is there a pattern? Consider the language used, how the photograph is staged, her surroundings.

Response of White Women to Black Immigration

Women’s groups, as reported in the Grain Growers Guide of 1911, were against Black immigration and they specifically wanted Black men to be denied the vote. Many women protested against the “Negro” as an eligible homesteader and instead urged that an order be passed making women eligible for homesteads.

The Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire (IODE) was first founded in 1900 to promote and sustain the British Empire and its soldiers. Although the first branch was started in Montreal it was not long before the IODE had chapters from Bermuda, India, and throughout the British Empire. Though the organization’s goals were primarily welfare-based and philanthropic, their compassion stopped short when it came to racialized and marginalized communities. The Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire was Anglophile women from the upper echelons of society supporting their Anglophile male counterparts through their charity events and memorials to promote imperialism and protect British Anglo-Saxon superiority in Canada and abroad.

“Homesteading offers a prospect to the worthwhile girl to make a place for herself in the world, instead of being a mere moneyed-husband hunter.

…..It should be possible for Canadian women to secure from the government of their fathers, husbands, brothers and sons at least an equal share with the foreign negro, in the rich heritage of the Dominion’s homestead lands.”

Regents (Presidents) of the IODE supported the Board of Trade resolution to the Canadian government, suggesting that “we do not wish the fair fame of western Canada should be sullied with the shadow of the lynch law but we have no guarantee that our women will be safer in their scattered homesteads than white women in other countries with a Negro population.”

Prominent Anglophile women such as Dr. Ella Synge, spokeswoman for the IODE, drew upon racist myths to explain White women’s fear of sexual assault by Black men. She claimed that “Surely the result of Lord Gladstone’s foolishness in South Africa is apparent enough already, in the enormous increase in outrages on white women that has [sic] occurred.”

She warned that “the finger of fate is pointing to lynch law which will be the ultimate result, as sure as we allow such people to settle among us.” – Edmonton Capital, 27 March 1911.

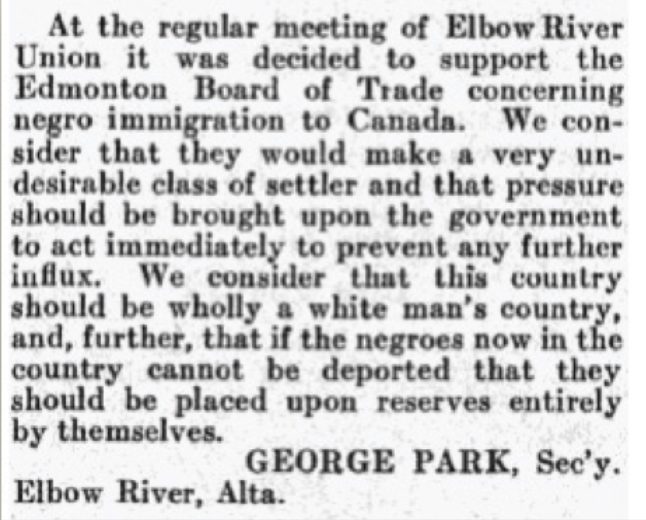

But the outcry about Black immigration to Alberta was not uniform. Popular magazines such as Farmers Weekly reported the responses of United Farmers of Alberta locals to the request from the Edmonton Board of Trade to support their resolution and petition arguing for the banning of Black immigration to Alberta.

Several supported the call for a ban, the Elbow River union argued

“we consider that this country should be wholly a white man’s country, and, further, that if the Negroes in the country cannot be deported that they should be placed upon reserves entirely by themselves.”

Farmers Weekly.

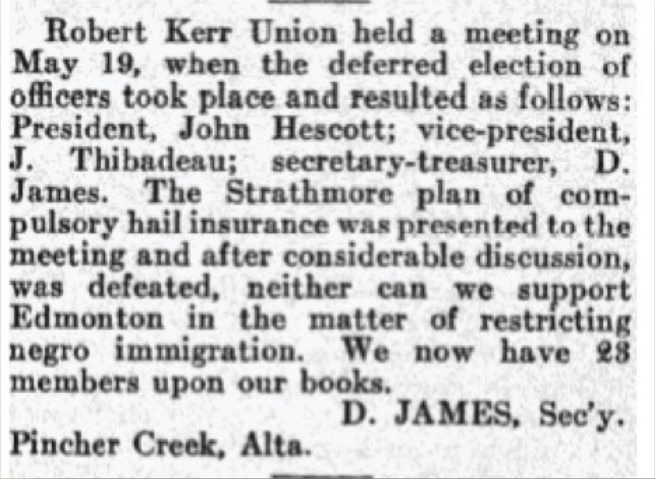

Whereas, the Robert Kerr union in Pincher Creek refused to support the Board of Trade position.

Farmers Weekly.

The letters to the newspapers demonstrate that not all Albertans were against Black immigration and some could see the class logic and racism at work in some of the protests and petitions by the Board of Trade and others. Even so, Rev. J. E. Hughson’s supportive letter does indicate the embedded nature of racialized understandings and betrays its superficial support with its underlying tenets of racism.

Rev. J. E. Hughson, of McDougall Methodist Church

“These are the voices of commerce and industry…they say the Negro must go. But Christianity tells us that the Negro is our brother, made of the same essential humanity. He may be our weaker brother. He may need our stronger hand to guide him, but he is our brother and we must act the part of a big brother toward him… When our commercial and industrial systems are really Christian, our Negro Problem will settle itself, because there will be no problem.”

Edmonton Journal, 8 May 1911.

Joseph A. Clarke

“There are other races and colours being welcomed by these same people into Canada who are just as much, or more, criminals and immoral and a far worse menace to the labouring majority of Alberta or any other country or province they invade, and boards of trade and other capitalistic appendages have no objections to offer.”

Edmonton Journal, 6 May 1911.

Letter from an American: This Virginian says the Junkins Negro Makes a Good Farmer

“You seem to have a wrong impression of these Negroes, if I may say so. There are Negroes in the South who lay around in the sun and never do a hand’s turn of work, but that isn’t your Junkins Negro. You’re going to see the day when you’ll be proud of him. He is a worker, he’s educated, he’s intelligent. I tell you sir, he’s a very advanced agriculturalist. Some of the Junkins Negroes have sent to Chicago to get their dairy stock. They have cows, pigs and chickens and crops and lots to eat. They are hospitable and intelligent. They are doing the best work we saw being done in all that country. I am surprised and proud to have to say it, sir.”

Black pioneers also challenged the myths perpetuated by those against immigration. Some Black folks wrote letters to newspapers while others followed around those trying to get Edmonton citizens to sign the petitions. A local paper reported the Black community members’ challenge to those seeking signatures for the Edmonton Board of Trade petition,

“The colony of colored people is up in arms against the movement. A number of them yesterday followed the canvassers from place to place in an effort to dissuade people from signing the petition. Whenever a request for a signature was made, a colored man was ready to intervene, with apparently little effect, although it is stated that a number of storekeepers in the east end who are more or less dependent upon trade of colored settlers declined to attach their signatures.”

Edmonton Capital, 27 April 1911.

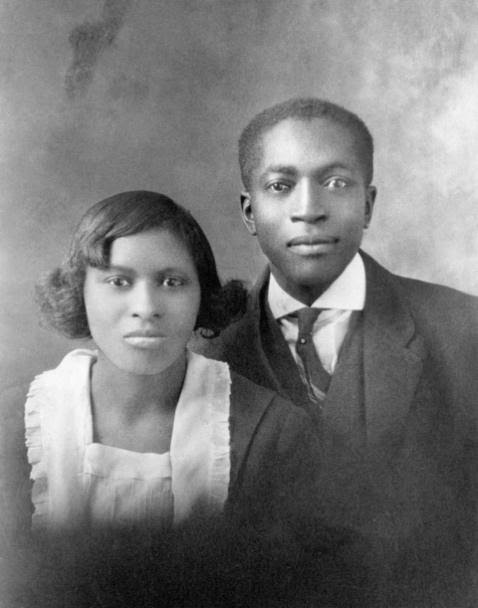

Despite the outcry against Black immigration during the early 1900s, the Black community grew from mainly individuals and a few families to four main rural communities Junkins, Pine Creek, Keystone, and Campsie. Consisting of groups of pioneer families, Pine Creek became the largest and most consistently Black community while the other three were mixed to differing degrees with European settlers. The communities, despite being “deemed unsuitable” by the Canadian government set up churches and in some cases schools alongside other institutions as the pioneers began to settle into rural life in Alberta.

Guiding questions

The racialization of peoples of African descent happened in the past but continues today.

- How do the media & the government continue to racialize people today?

- What kinds of harm does racialization cause?

- What will you do to challenge the racialization and racism experienced by fellow Albertans? How will you change your own individual behaviour?