And Still We Rise

A Black Presence in Alberta, late 1800s – 1970s

Researched and developed by Dr. Jennifer Kelly

Black history is Alberta’s history. In this exhibit explore the formation of Alberta’s Black communities from the late 1800s through to the early 1970s. Although Black peoples encountered racism in Alberta they were also active and assertive in challenging such instances.

Image courtesy of the Athabasca Archives, 14375.

The title for this virtual exhibition draws on a poem by African American writer and poet Maya Angelou entitled, “And Still I Rise.”

You may write me down in history

With your bitter, twisted lies,

You may trod me in the very dirt

But still, like dust, I’ll rise.

Introduction

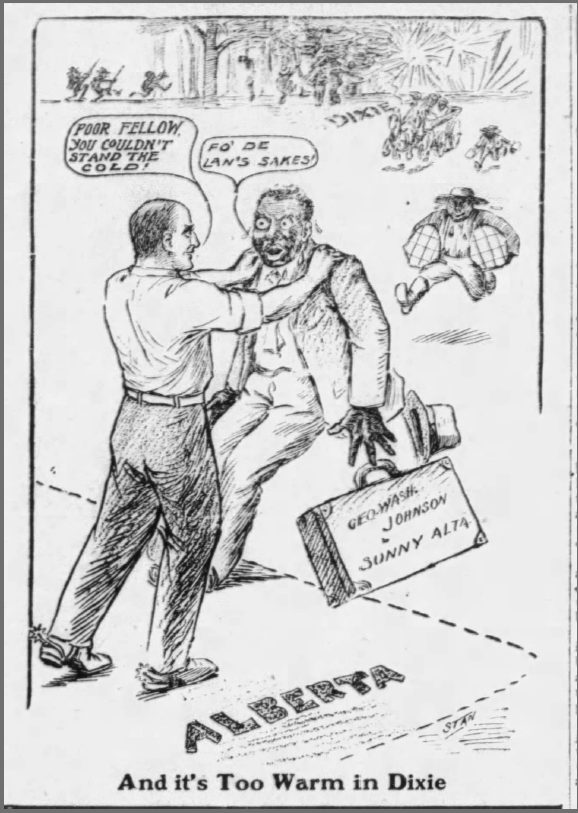

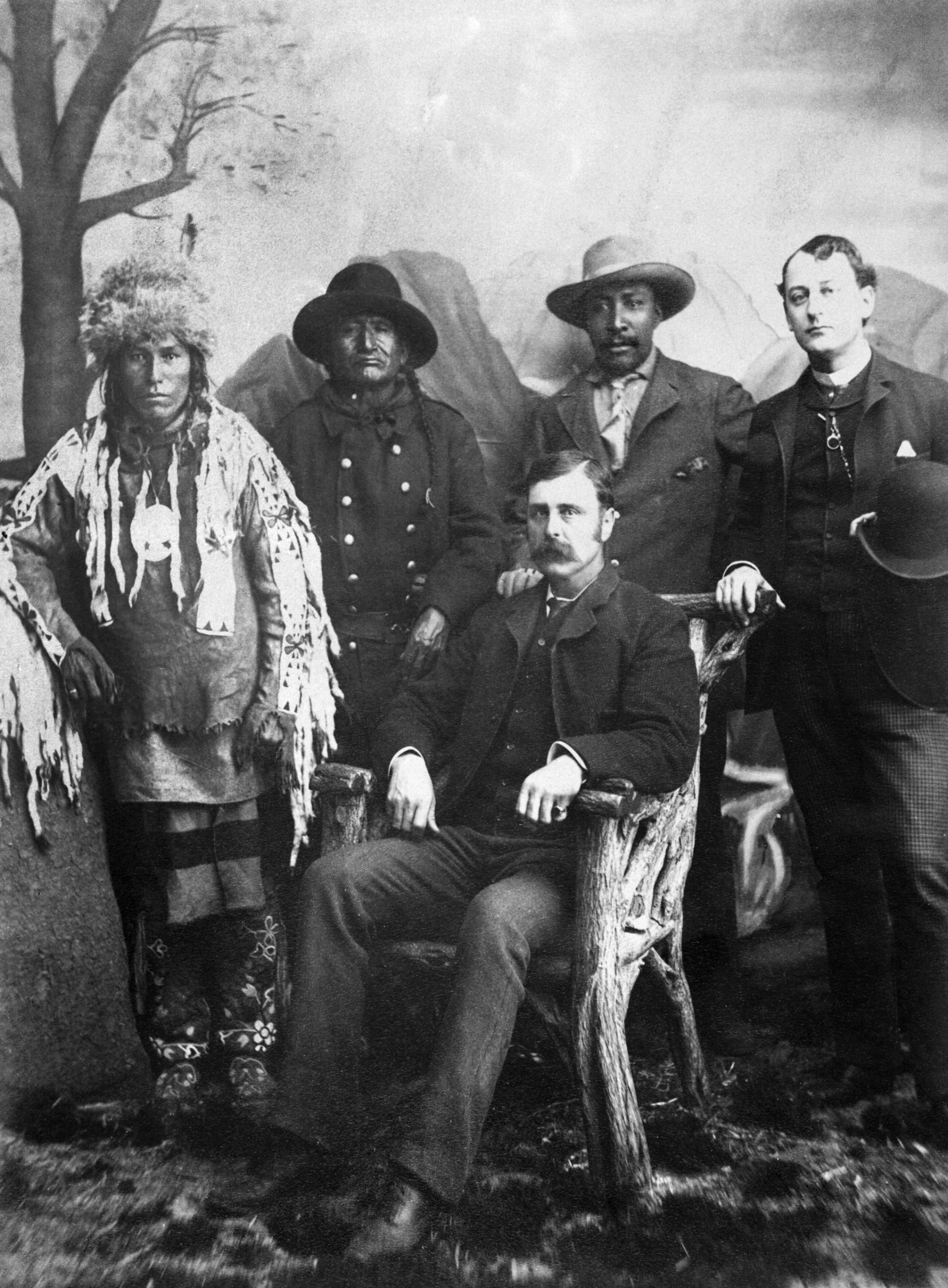

This photographic exhibit acts as a counterstory to broader and commonplace stories of Black people as not present in Alberta history, and their consequent displacement. It is a counterstory that highlights the making of a white settler society through the weaving together of imperialism, capitalism, racism and gender to create a social order that is still with us today. This making of a male-dominated white settler society resulted in the displacement of Indigenous communities and the exclusion of others racialized as not white.

As the virtual exhibition illustrates, Black Albertans did make history, and we can therefore rightly claim that Black history is Canadian history and central to our understanding of the formation of Alberta.

Within the exhibit we view a continuation between the past and the present in terms of how our community has been, and still is, represented as deficient citizens as lesser-than, especially when placed in relation to the constituted whiteness of Alberta.

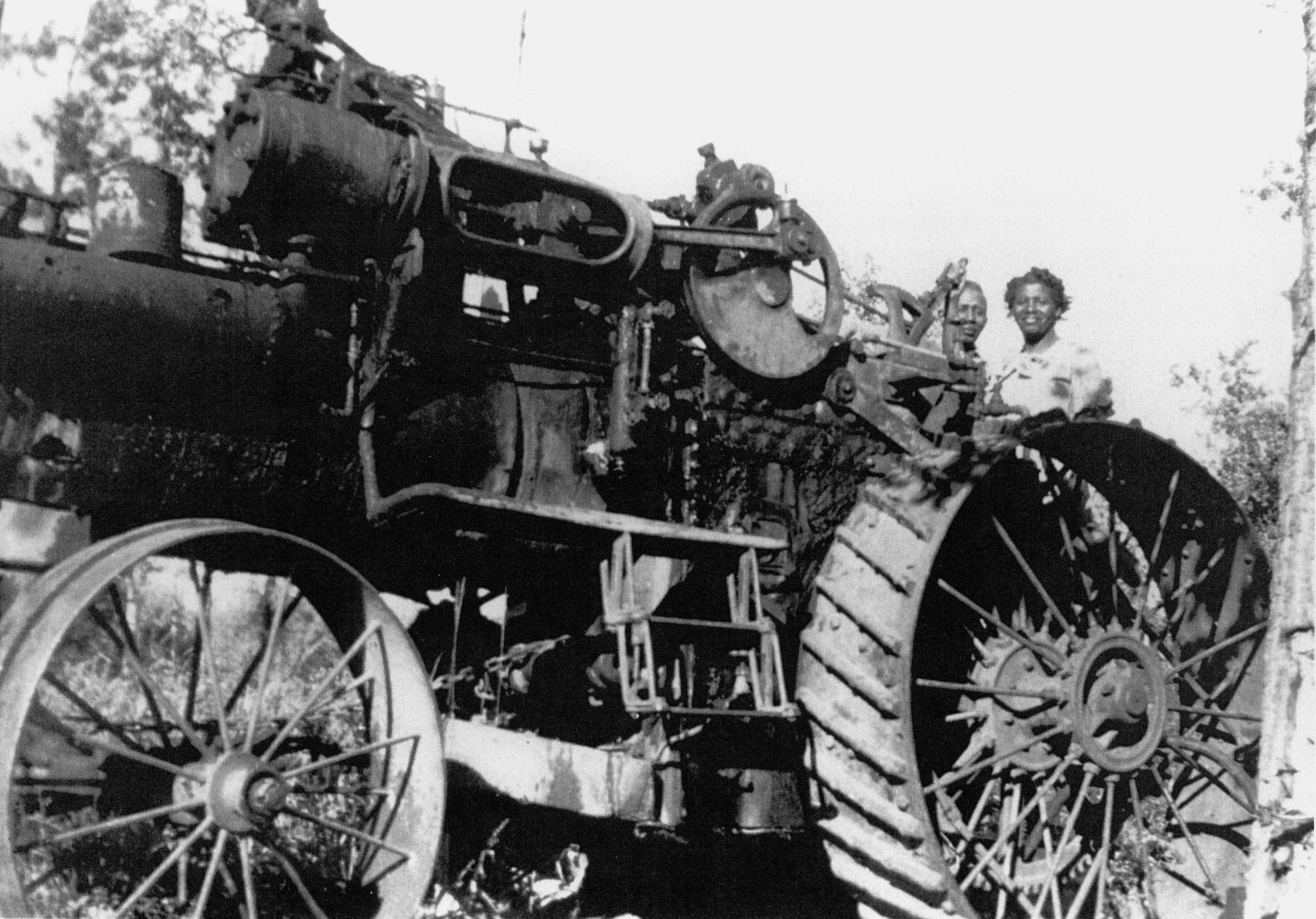

The history of Black people in what is now known as Alberta began in the fur trade era with Black Canadians arriving as individual pioneers or accompanying traders and surveyors in the 18th and 19th century.

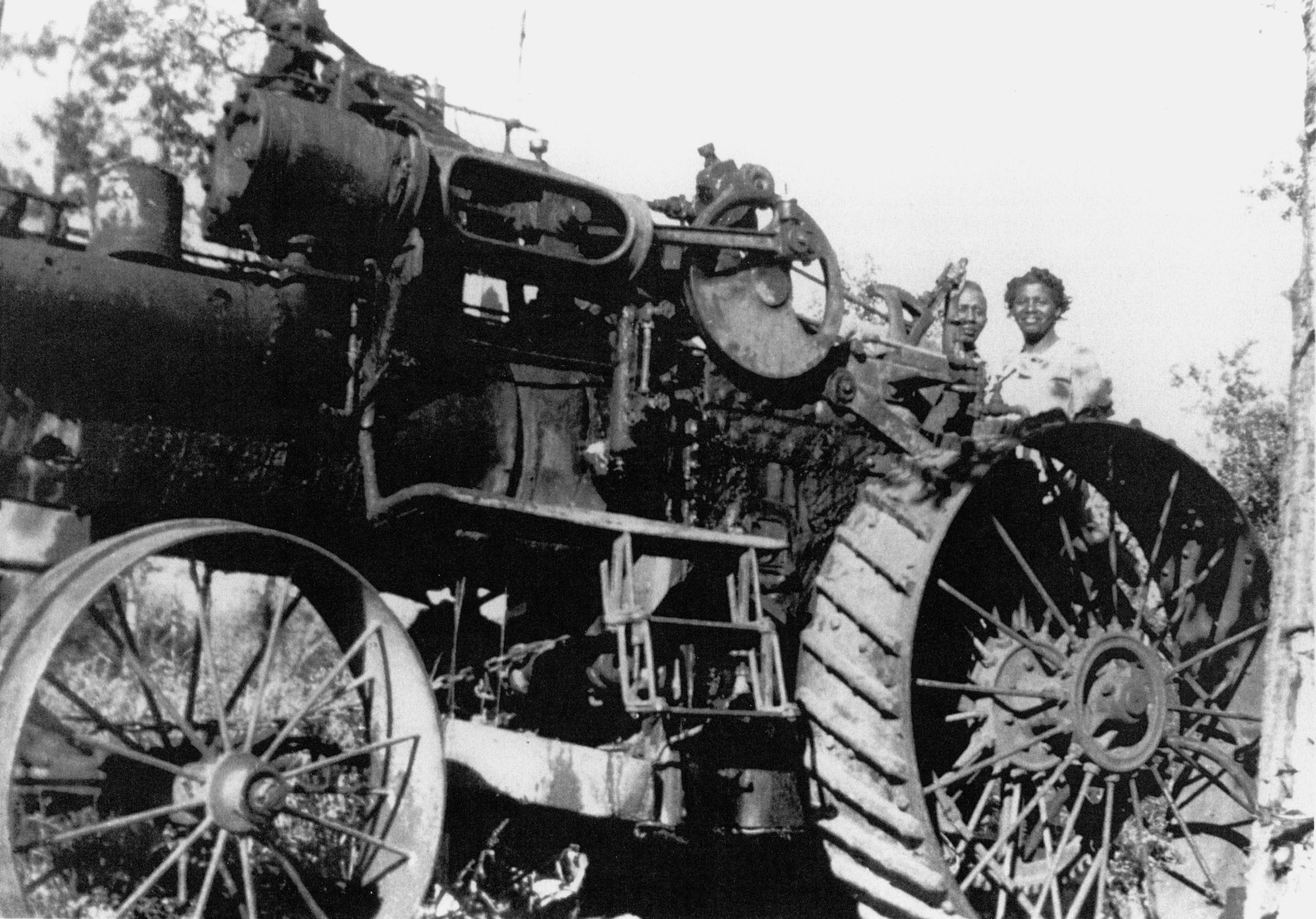

In the early 1900s, advertisements promoting “free” homesteads appeared in American newspapers, including publications in Black communities in the American South. Eager to escape increasing discrimination, segregation laws, and voter disenfranchisement, some Black families from the United States chose to immigrate to Western Canada.

In Alberta, families settled together to form four main rural communities: Junkins, Keystone, Campsie & Pine Creek. Edmonton & Calgary were also home to a growing number of Black families. They soon set up churches and, in some cases, schools within their communities.

The Depression sped up a slow drift from rural Black settlements to cities and towns for economic opportunities – including an increasing number of men who worked on the railways. The communities were active in fighting for their rights through court challenges and the formation of political & social organizations often associated with local churches.

After the WWII, the composition of Black communities in cities began to change as athletes from the United States, Caribbean women under the Domestic Workers Scheme, and a few “meritorious” Black individuals were allowed to move to Alberta.

Back row, L-R: P.T. Clay, Wilbur Milton, Jeff Bowen, Willis Richardson, ‘Doomy’ Hicks, Embert ‘Amos’ States, Melvin Crump. Middle row, L-R: Peaches Coleman, Willa ‘Gotchie’ Sneed, Louella Bellamy, Ethel Kay, Alex Kay, Rachel Walton, Charlie Walton. Front row, L-R: Ray Williams (holding Judy Williams), Odelle Holmes, Mr. Blanchette, Helen Braithwaite, Cordie Williams.

While Black Canadians faced racism, discrimination, racialization and social exclusion they also resisted, advocated, and supported their communities through labour unions and religious institutions. Organizations such as the international union of Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (above) and the Alberta Association for the Advancement of Coloured People were pivotal in bringing about changes in employment and accommodation practices.

With the successful fight for changes in the discriminatory immigration laws and practices in 1962 and 1967, more Black peoples from the Caribbean region and countries in Africa were allowed to settle and become Canadian citizens.

Image courtesy of Glenbow Archives, Archives and Special Collections, University of Calgary, NA 56000-7757A.

Among the newcomers were oil workers, stenographers, postsecondary students, and teachers. Black Albertans have continued to contribute to the history and social fabric of our province in numerous ways.

About the Exhibition

The virtual exhibit A Black Presence in Alberta: late 1800s – 1970s was researched and developed by Dr. Jennifer Kelly. It is based on a previous physical exhibit developed by Dr. Jennifer Kelly and produced by Dr. Kelly with assistance from Dan Cui with funding support from Edmonton Heritage Council, Canadian Heritage, and the Social Sciences Humanities Research Council.