During this time, we begin to see a change in the demographics of the Alberta-based Black Canadian community as folks who came from the United States in the early 1900s begin to encounter people recently arrived from the United States, often as athletes, and those who were arriving in increasing numbers from the Caribbean.

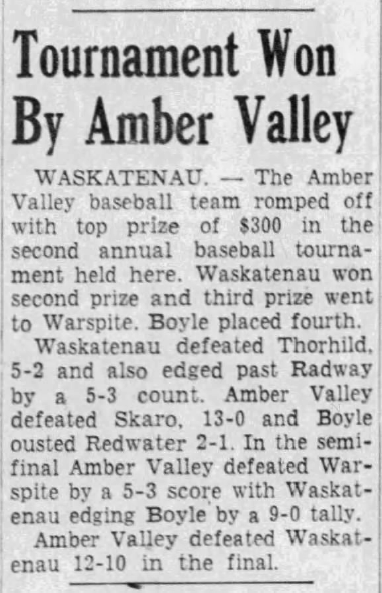

In the 1950s, Black sports personalities began to gain celebrity status. As well, professions began to open up for those from traditionally marginalized groups. While early pioneers such as J.D. Edwards continued to feel at home in rural areas such as Amber Valley, others moved to major cities such as Calgary and Edmonton. The Amber Valley baseball team, made up of descendants from the early pioneers, was still doing well in the 1950s.

Many of the Caribbean folks who immigrated to Alberta came as teachers, court clerks, stenographers and oil workers. Their arrivals increased the diversity within Alberta’s Black community. Many of these newcomers were from different countries, of different ethnicities, and held different religious beliefs.

Premier Manning’s Social Credit government was slow to pass legislation banning discrimination in Alberta. Manning, for religious and ideological reasons, opposed interference with the rights of owners, employers, and landlords. Individual rights championed by human rights campaigners often conflicted with the rights of owners of capital.

In the mid-to-late 1950s and early 1960s, increasing numbers of non-White workers and their supporters attempted to challenge barriers that maintained all-White occupations in public service and professional jobs. By the 1960s, jobs such as transit bus driver and firefighter became possible for Black workers living in Edmonton and Calgary.

Theodore (Ted) King & the Alberta Association Advancement Colored People

Many Black Canadian soldiers fought in the Second World War. Although there were no segregated battalions as in WWI there were still some difficulties being accepted into perceived elite units such as the Royal Canadian Air Force and Royal Canadian Navy. The contributions of soldiers affected some attitudes about segregation that were prevalent in wider Canadian society but racism continued to be a factor in society.

Among those veterans was Corporal Theodore (Ted) King, seen here with his mother, father, sister Violet and future wife, Della Mayes. In 1953, Violet King graduated from the Faculty of Law at the University of Alberta and, in 1954, became the first Black woman in Canada to be called to the bar as a lawyer.

Ted King was a porter from 1946 to 1953, an accountant, and President of the Alberta Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (AAACP) from 1958 to 1961. In 1959, he sued the owner of Barclay Motel in Calgary after being denied a room because he was Black. Although the owner’s racism was blatant- having told King several times that he did not house “coloureds”- the Albertan judge ruled in Barclay’s favour.

King unsuccessfully contested the decision in the Alberta Supreme court. Despite the loss, the court case helped to highlight and change legal gaps that allowed innkeepers to deny service to Black people.

Alberta Association Advancement Colored People

Alberta Association Advancement Colored People (AAACP) was formed in Calgary in the 1950s. Their membership, aims, and purposes overlapped with concerns voiced by the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. The Association highlighted three main items worthy of attention: employment, social practices, and housing.

Mojo Williams being interviewed by Dr. Jennifer Kelly & Donna Coombs-Montrose, October 2001

Mojo Williams was born in Calgary in 1946, a third-generation Canadian whose grandparents had fled racist harassment in Oklahoma to farm in Canada. His dad was a railway porter and shoeshiner and his mother worked as a domestic for wealthy whites.

His fighting spirit led him to become the grievance officer for the Alberta Association for the Advancement of Coloured People for many years beginning in the late 1960s. Black people in Calgary asked him to intervene in cases involving discrimination in housing, harassment in workplaces, the barring of Black people as customers in nightclubs, and discrimination faced by Black children in Calgary schools. Williams focused on efforts to persuade those accused of specific instances of racism that they or the institutions that they were part of would suffer reputationally if they did not end their discriminatory practices.

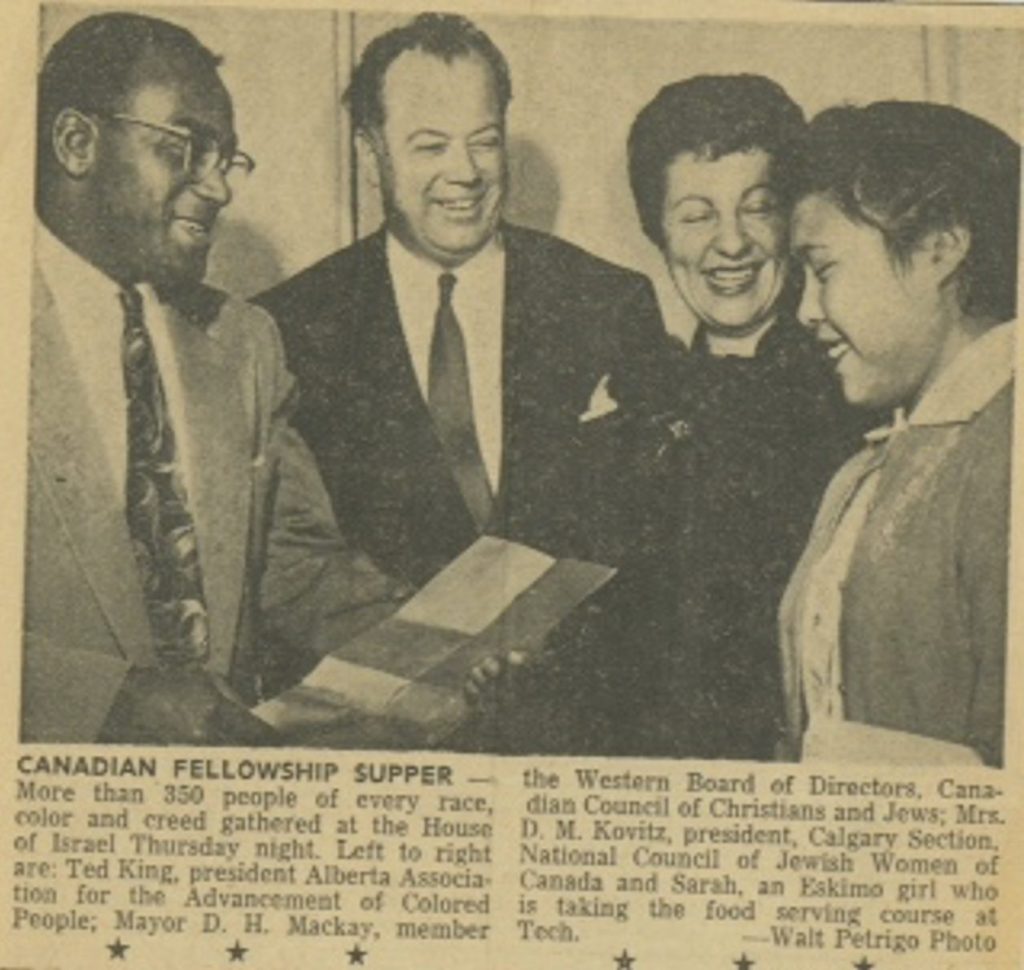

In their efforts to advance social practices in Calgary, the AAACP often cooperated with groups such as the Council of Canadians Jews and Christians.

“Canadian Fellowship Supper –

More than 350 people of every race, color and creed gathered at the House of Israel Thursday night. Left to right are: Ted King, president of Alberta Association for the Advancement of Colored People, Mayor D.H. Mackay, member the Western Board of Directors, Canadian Council of Christians and Jews, Mrs. D.M. Kovitz, president, Calgary section, National Council of Jewish Women of Canada and Sarah, an [Inuit] girl who is taking the food serving course at Tech.”

Image provided by Dr. Jennifer Kelly courtesy of Mrs. Della King, circa 1950s.

Concerning employment, AAACP member Dick Bellamy suggests:

“I would like to point out here that about 80 percent of the colored people in Calgary work in the capacity as railroad porters; either for the CPR or the CNR. I started to work for the CPR in 1927-32. Years ago, wages were very low. It was very hard to support a family and $70 per month plus sending your child to school.”

Bellamy illustrates the types of occupations that young people were encouraged to enter into:

“Since I have been affiliated with the NAACP, we have encouraged our young colored people to take shorthand typing in some of the business colleges and if they were fortunate to finish we could approach some of the business in men of the city in regards to placing members of the race in certain jobs they were qualified to do. At present we have a young lady working at Hudson Bay; a young man works at Eatons’ Post office and others.”

During the Second World War, folks who remained in Alberta found that opportunities began to open up as traditional “first picks” for jobs (able-bodied white men) were not available in sufficient numbers for work.

Dick Bellamy, a porter and member of the AAACP recalls,

“At the outbreak of the war those who were left behind found other jobs in aircraft, factories, chemical plants. Their jobs paid more money than railroading. Consequently quite a few of the men quit the railroad, this in turn helped to raise the standard of living of the colored people. There were families whose children had to quit school in the 7 or 8 Grade because their parents couldn’t afford to keep them in school.”

Guiding questions

- What stories about the past should I believe? And on what grounds do I believe them?

- Which stories from the past do we tell? Which stories are excluded? What types of stories should we tell?