Before the mid-1960s, few immigrants of African descent were allowed into Canada. Because of the racist white preferred immigration rules and regulations, “admittance of ‘coloured or partly coloured persons’ was restricted to certain classes of close relatives of Canadian citizens and cases deemed as having exceptional merit.” The only other state mechanism for immigrating to Canada before the early 1960s was through the West Indian Domestic Scheme for single women workers.

West Indian Domestic Scheme

In 1955, the Department of Citizenship and Immigration implemented “a special form of contract labour scheme for groups of ‘colored’ domestics from Jamaica and Barbados.” The Canadian Immigration officials were not keen on such “group immigration” and preferred that people from the Caribbean come to Canada as individual skilled immigrants designated as being meritorious and capable of filling specific job shortages. In comments to the Minister of Citizenship and Immigration, Deputy Minster Isbister noted that “some of those coming to Canada as domestics could have qualified in their own right for admission to Canada as typists, stenographers, beauticians, teachers, nurses, etc.” (1964)

One young woman, Cora, emigrated from the Caribbean under the Domestic Workers Scheme in 1956. Flying directly to Montreal she worked for some time before moving to Alberta. Before arriving in Canada, Cora worked as a sales clerk for three years. When asked why she decided to immigrate to Canada, Cora stated:

“In the West Indies if you don’t leave the country you were a nothing. You have to leave the country to become somebody and you … get status.”

Some interviewing officers were keen to promote certain gendered and political values:

“We were told in advance by this girl at Hilton Hotel how to attire ourselves. So, I went up there, put on my suit or whatever…. At the time, if you had a big afro [then] you’re Black power, which is stupid, but that’s the way they branded it.”

“When I went for my interview and he said that I was successful… He said to me, ‘while I’m allowing you to come to Canada, you have to know that you can either make or break it; a wife can either make or break it. Your job is to make it. You’re going to Canada and right now they have this thing about women’s lib’ and [he warned me not to get] involved in that.”

At times, transitioning into a new Canadian environment was gendered and, on arrival in Edmonton, some single women from the Caribbean chose to initially live at the YWCA.

“Pictured above with Mrs. Conquest is Cynthia Green, one of several Jamaican girls now living in Edmonton, who will serve coffee Thursday evening. The coffee party is being arranged in aid of world service projects and will be attended by Mrs. Ryrie Smith, of Toronto, national president of the YWCA, who will be a visitor in Edmonton this week.”

Edmonton Journal, 2 March 1960.

As a single young woman new to Edmonton, the YWCA offered a sense of connection and safety in a new environment,

“When I came to this country first …I lived at the YWCA… and I lived there for a year, or a little over a year, and we had all the girls that just came up from Trinidad, … because most of them were going to school. And although I was working, I was able to [live] there, they had an age limit where you can only stay there ‘til you’re thirty, …mainly had young girls that were away from home…. It was a very safe environment for us really. I mean…it was a home away from home. We had a Resident Director, we had curfew.”

Guiding question

- The West Indian Domestic Scheme allowed for single women workers to immigrate to Canada.

- Imagine you are a young woman moving to Canada alone. You are not allowed to bring any family with you. How would that make you feel?

Even though there was a severe shortage of people with experience and training in the administrative field, Rachel found it difficult to get a job due to racism.

“Alberta had a lot of jobs especially in the administrative field because you could simply phone up and they’ll ask you to come for an interview. … So many a time I would phone up and go for an interview; and when I got there, my skin tone was wrong…. One place that I went, the guy actually voiced it. He said ‘I was expecting someone different. I’ve never met a [B]lack person.’ And, so, that was the discrimination. … In fact, the job I ended up getting – when I called up, I said to the guy, ‘you just need to know before I waste my time and yours that I’m [B]lack. If it doesn’t matter to you, it doesn’t matter to me.’ I went in for the interview and I actually got the job. But mostly people can’t hide their disappointment, and they can’t hide their faces like…. You cannot hide red faces.”

One recruit with skills and knowledge garnered in the Trinidad oil industry recalls his early days in Fort McMurray:

“That was the first plant they had built extracting the oil from the oil sand. . .I’d never worked in a plant like that before, so this was something new. They used big bucket wheels to dig the sand. They put it in a big drum and hot water to help dilute or extract the first set of oil, then it goes into other stages before they can get it to refine. . . . In Trinidad, we have refineries and I’d worked there before. But the weather [in Alberta], this was a big problem. The weather, I didn’t know what it was like.”

Many new immigrants had their previous educational achievements questioned and devalued. One professional worker who emigrated from St. Lucia in the early 1960s recalls her experiences with immigration authorities on arrival in Canada and their assumptions about inferior educational systems in the Caribbean. On being told that she would have to take a grade 12 English course she responded,

“I told them, ‘English Grade 12?. . . But I’ve spoken English my whole life.’ I may have had a West Indian accent at that time, ‘but [I told him] my English is better than your English.’”

Brian Alleyne being interviewed by Donna Coombs-Montrose, 2014

Watch

British-trained Brian Alleyne arrived in Canada as a Landed Immigrant in 1969, only to discover that none of his medical / technical credentials were recognized – unlike the experience of his fellow Britishers; he was forced to begin postsecondary studies again. At Sir George Williams University, Alleyne found brilliant Caribbean students experiencing the same plight of constant and deliberate failing grades. Their racialized experience led to the seizure of university property.

In 1962, as a result of protest by Black communities in Canada and the Caribbean, changes were made to the White-preferred immigration rules and regulations to assess applicants based on skill- supposedly irrespective of race, ethnicity, or country of origin. In 1967, a further change in immigration policy enabled the introduction of a points system based on education, language fluency, and job skills opened up further opportunities for Black immigration.

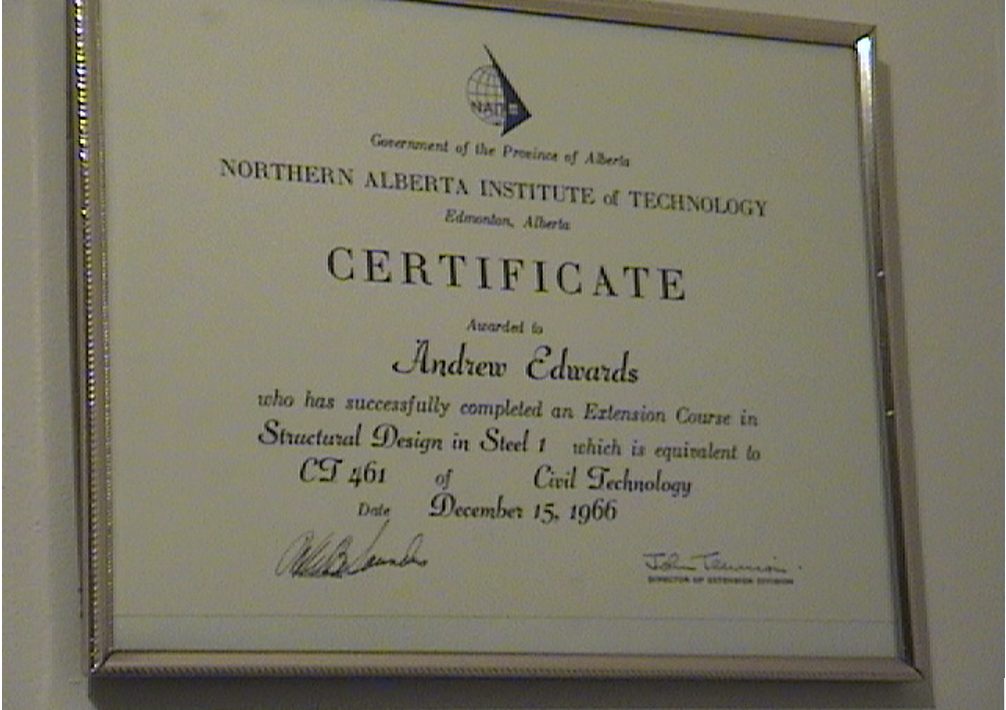

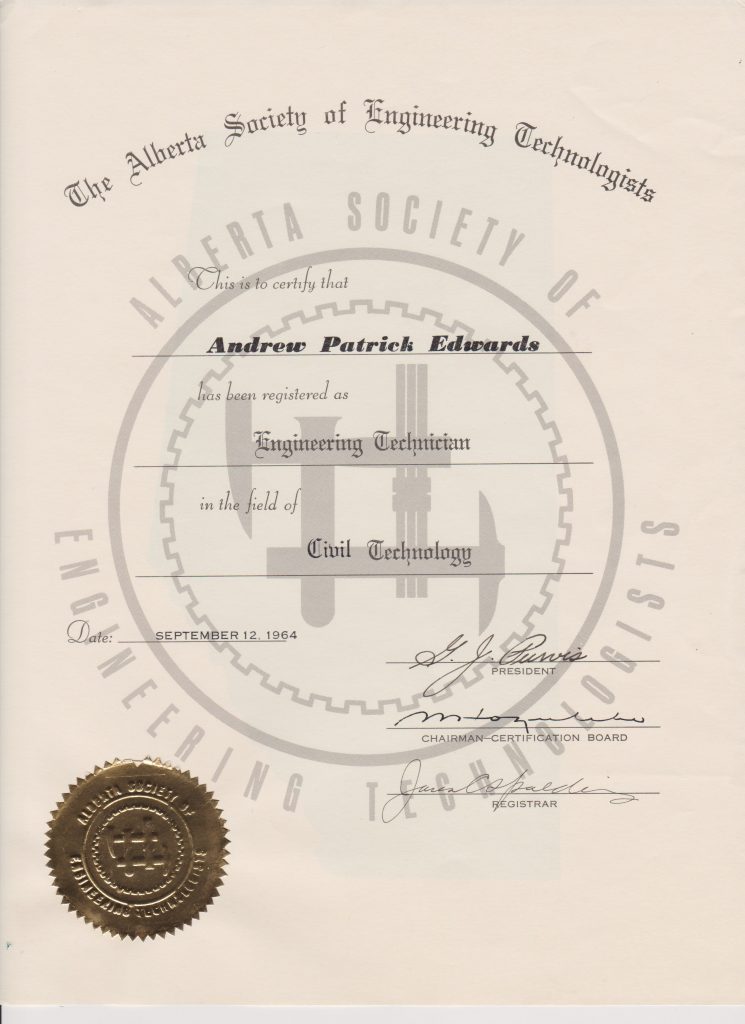

Most newcomers returned to study so that they could increase their future employment in Canada. Some went to the University of Alberta or the new University of Calgary while others went to Northern Alberta Institute of Technology.

The group who came in the early 1960s were dynamic and provided the basis and leadership for many new organizations in the 1970s and 80s. For example, Andy Edwards was associated with the Edmonton Caribbean Cultural Association and its newspaper the Communicant. Other organizations included the Jamaican Association Northern Alberta, Council of Black Organizations, Mico Old Students’ Association.

Andy Edwards came from Trinidad and Tobago in the early 1960s. He studied engineering at the Northern Alberta Institute of Technology (NAIT) and became a member of the Alberta Society of Engineering Technologists. He was active in the community working to organize a community group called Edmonton Caribbean Cultural Association (ECCA).

“The Edmonton Caribbean Cultural Association “ECCA” which Mike Lancaster and nine others including myself [Andy Edwards], founded and incorporated in March 1978, after the then existing West Indian Society folded. ECCA represented people from all the Caribbean Islands who resided in Edmonton at that time. We participated in all of the cities Social, Cultural and Political activities”

“The group Caribbean Perspective, founded by Selwyn Jacobs in mid 1978. Between 1978 and 1980 this group produced 36 TV productions for the Capital Cable Television, the shows were about the Caribbean community in Edmonton, and also featured official government representatives from the various Caribbean Islands, as Guest Speakers”

Andy Edwards quotes courtesy of AndrewPatrickEdwards.com.

Selwyn Jacob being interviewed by Donna Coombs-Montrose, 2013

Watch

Trinidad-born Selwyn Jacob came to the University of Alberta in 1968 to pursue postsecondary studies in drama and film production. Part of the new wave of Caribbean student migration to Canada, Jacob was an early occupant of the “West Indian House” – today’s Timms Centre on campus – which pioneered West Indian culture and developed West Indian Week as a teaching and community vehicle for cultural integration. The WI House served as a coop/ community centre and home for all West Indians living in isolation. Several pioneering Caribbean groups were also formed and housed there, including Caribbean Ambassadors, Tropical Playboys and a steelband.

Video courtesy of the Alberta Labour History Institute.

One University of Alberta student remembered the importance of coming together at West Indian House, a fraternity-style house on the U of A campus:

“West Indian House, past Campus Towers. Jamaicans, Guyanese, Trinidad. Go to play ping-pong or cards, to cook as a group. We could always congregate there. House filled but couldn’t live [there]…. Through the Association we highlighted West Indian Week on campus. Collected crafts and displayed on tables. We also had music and we also would demonstrate a few of the dances e.g. limbo.”

The Black community within Edmonton is diasporic, consisting of descendants of the early pioneers, folks from Caribbean islands, and the many countries in Africa. Occasionally, these communities come together for events such as a draft play reading of West Indian Diary, written by Pat Darbasie and based on Dr. Jennifer Kelly’s research with Caribbean immigrants who arrived in Canada between the 1950s and 1970s.

Where is Home?

“I had to evaluate where home was and who I am. Home is where I am, where I choose to live, and I came to that point. But it was a soul searching because sometimes people ask you things. For the longest time, I used to tell people … only because they would ask me about Grenada and I felt very embarrassed because I didn’t know anything about it. And it was almost ‘what do you mean you don’t know?’ So, I can’t ask any more questions you know.

I also had this question what does that make you? Because when I think of home, I really do think about England and the question is ‘is it because it is home or is it because that is where my family are?’ And I come to the understanding it is home because that is where my family lived. My parents, my sisters, my aunt is there. So, home is where the heart is really and family lives. And then, this is home now. When I’m there, I say I’m going home now that I have my children here, and hopefully one day grandchildren. This is home now … home really becomes where the heart is. And I tell my children this. You guys will want to care. This is my home I chose to come here. This is my home of choice. Anybody who tries to tell me different things … I chose to come here. I had a home … I wasn’t a homeless – I chose to come here.”