For 70 years, Mike’s News Stand was an Edmonton institution. For most of that time, it operated from a storefront at 10062 Jasper Avenue, and its animated neon sign was a famous downtown landmark.

The sign, with a legs-crossed man reading the Toronto Star Weekly and with one leg that swung back and forth as if by magic, was erected above the entrance in 1934. “News…Smokes,” the sign shouted to Jasper Avenue passersby. Now, it hangs proudly once again as part of the Neon Sign Museum on the side of the Telus building on 104th Street and 104th Avenue.

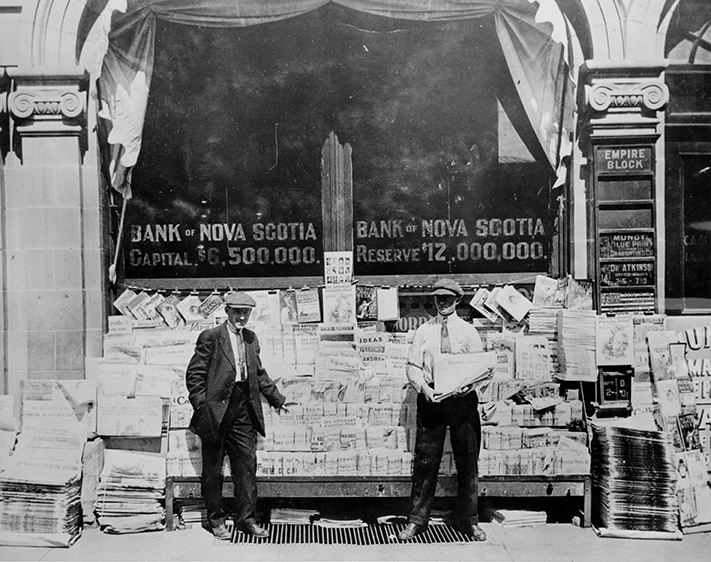

- Mike’s News Agency, 1908, showing John Michaels and Bob Wright. City of Edmonton Archives, EA-10-1587.

- Mike’s News sign in storage, 1998. Photo by Lawrence Herzog

The store itself opened for business on Tuesday, December 5, 1916, and was called Mike’s News and Tobacco Stand. Named for its owner John Michaels (who everybody knew as Mike), it was billed a place where citizens could send magazines or periodicals and smokes to boys on the front, fighting in the First World War.

Mike’s quickly became the place to go to hear the local gossip, the fascinating exploits of the bush pilots who gathered there and catch the latest sports scores. Each day, newsboys would fan out from the store along Jasper Avenue, shouting “extra, extra, read all about it!”

Michaels was only ten years old when he began selling papers on New York’s Lower East Side in 1901. When he landed in Edmonton in 1912, he had just turned 20, and it was natural that he kept on doing what he had done so enthusiastically in the Big Apple.

He and fellow newsboy Bob Wright set up operations on the corner of Jasper Avenue and First Street (101st), becoming one of Edmonton’s earliest and most successful newsboys. When the weather was bitterly cold, as it often was in the winter, the two young men would work a half hour outside and head inside for an hour to thaw out.

As an entrepreneur of unbridled energy, he began selling pennants at the Eskimos and Dominions hockey games at the Edmonton Arena, which later became the Gardens. He landed contracts to distribute papers to other newsstands from the three dailies – the Bulletin, the Journal, and the labour paper called the Capital.

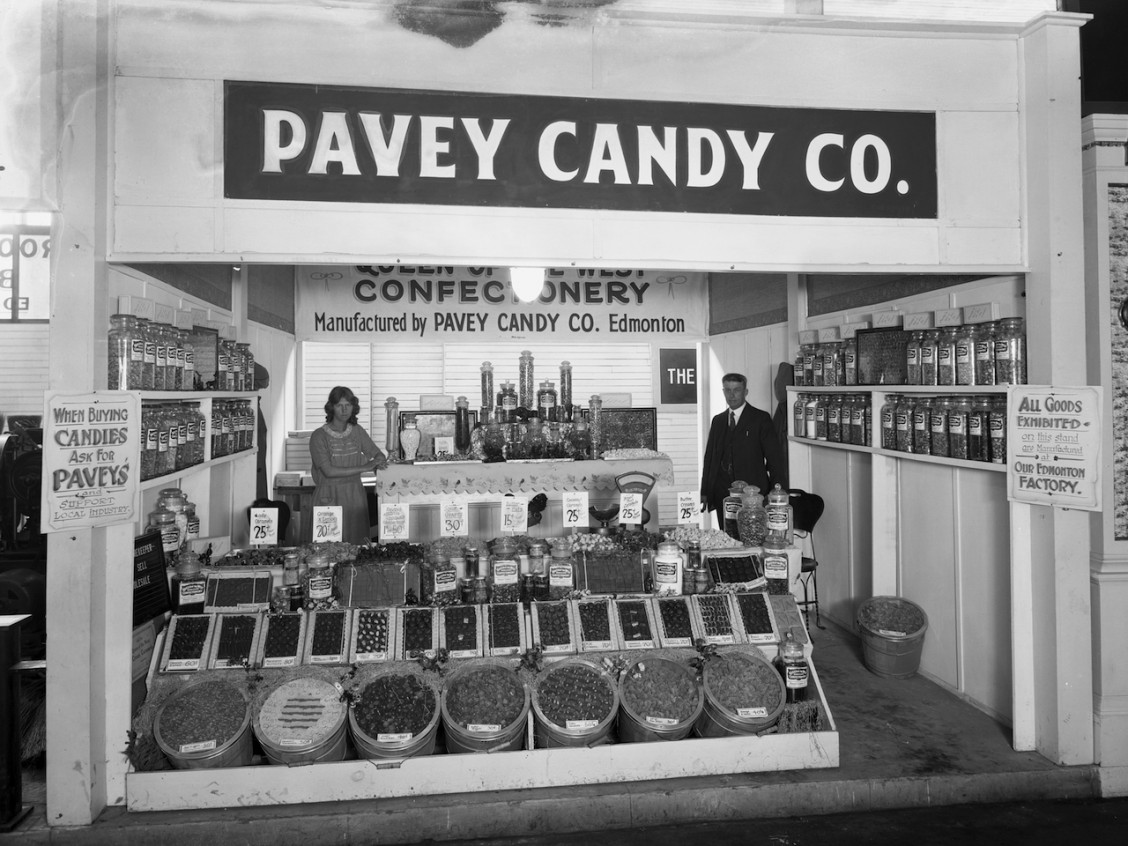

Business was good, and he prospered. Edmonton was, after all, a city where most everybody had come from somewhere else, and there was a lot of demand for printed news of the world.

“Old country papers!” he would cry out at the throngs coming and going. “Your hometown paper from all over Canada and the United States – Chicago Blade and Ledger, Calgary Eye Opener, Toronto Star…”

Throughout his life, Michaels never lost his Brooklyn accent and expressions. He was a born hustler who knew how to make a buck, and had a hell of a time doing it.

In 1913 he approached the Edmonton Journal for sponsorship help and organized the Newsboys’ Band as a way to curb juvenile delinquency. He raised money to purchase instruments and donated some of his own. Over the next 20 years, more than 1,800 newsboys played their way through its ranks.

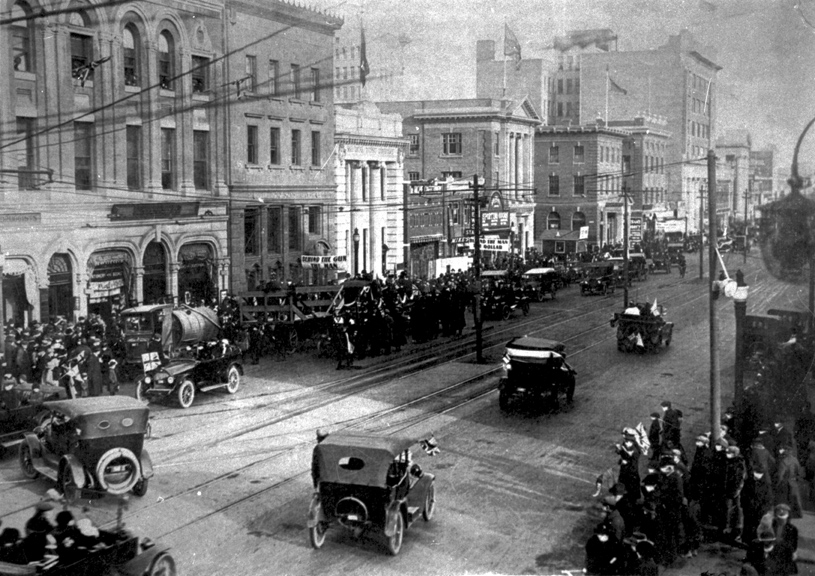

- Edmonton Journal Newsboys’ Band, 1913. City of Edmonton Archives, EA-744-1

Tickets at Mike’s started operations in 1918, selling tickets for local sports events including hockey, football, basketball and baseball. Michaels was a fanatical sports fan, and around 1920 he had a special telegraph wire run to the store, so that on game days he could receive telegrams from distant rinks or fields and keep up-to-the-moment with the scores.

He would read the updates aloud using a megaphone to customers inside the store and, sometimes when the crowds got really large, to those assembled on the front sidewalk. Fans could also phone 22020 to get the latest scores, and thousands of Edmontonians knew the number by heart.

Michaels parlayed the success of Mike’s News Stand into some other ventures including bowling alleys, mines and aircraft. When the Depression hit in October 1929, he began the tradition of serving Christmas dinner to ex-servicemen at the Montgomery Legion. Many of them were homeless.

For his efforts during both world wars, Michaels was bestowed with the Order of the British Empire. In recognition of his efforts to supply reading material to Canadian and American army personnel during the Second World War, he was awarded the Medal of Freedom, the highest U.S. award to civilians. In 1945 he was named by the Junior Chamber of Commerce as Edmonton’s Citizen of the Year.

With its ancient worn linoleum floor, tin ceiling, varnished wood magazine and newspaper shelves darkened by time, distinctive fragrance and cacophony of sounds, Mike’s News Stand was a singular experience. The floors creaked under the coming and going of customers, and the tang of Cuban cigars and pipe tobacco hung in the air. The storefront had housed a shooting gallery in an earlier existence and had bullet holes near the ticket office sign to prove it.

- Display window, Mike’s News Stand, April 17, 1947. City of Edmonton Archives, EA-600-21a

- Interior of Mike’s News, 1949. City of Edmonton Archives, EA-160-1369

At its peak, the store carried some 3,500 different magazines and more than 20 non-English newspapers. Staff set aside titles for regular customers, stuffing them into one of 400 marked “pigeon holes” at the back of the store. Customers could browse as long as they liked, and some were renowned for reading at their leisure and then dog-earring the page they finished at so they could resume when they returned.

In a Journal story commemorating the store’s 50th anniversary in 1966, writer Toni Ross noted that “whenever anything happened, Mike’s was the place to go to rehash the event.” It was a place where “bush pilots stood about the potbellied stove and charted courses over new areas,” and “citizens stood in zero temperatures to watch hockey scores of the 1920s posted on a huge billboard after they had been rushed through by direct telegraph wire.”

Bob Wright, the longtime manager, remembered when reinforcements for the 49th Battalion were marching by on Jasper Avenue on their way to battlegrounds of the First World War. “Mike ran out and shouted, ‘Hey, Scottie, your old country mail is in.’ He dashed out and handed the paper to the soldier, saying: ‘Man, you can pay me when you come back.’” Nearly four years later, the soldier came to Mike’s to pay for his paper.

Michaels retired in 1957 and died in 1962 at the University Hospital at the age of 71. He was survived by his wife Ruth and daughter Audrey Lovelace. The neighbourhood of Michaels Park at 38th Avenue north of Whitemud Drive, 66th Street to 76th Street, was later named by the City in his honour.

When the Edmonton Exhibition Association revamped ticket sales in 1976, Mike’s took a heavy blow. It was the most popular ticket vendor in town, and business tumbled. The Michaels family sold the business in August 1978 to Arnold Sacher.

“Our most sincere thanks to all of our customers, some of whom remember us for many of our 62 years in the same location,” read a newspaper ad that ran in local papers on August 18th. “Our gratitude to the loyal staff who will continue to serve you and to Mattie Harvey and her family at Mike’s Ticket Office who have afforded us a long association.

“It will be business as usual,” the ad concluded, “only the ownership will change. To the new owners, we wish more than 62 rewarding years.”

Two years later, with plans afoot to demolish the building Mike’s had long called home and construct gleaming new Scotia Place, the news stand relocated to a sterile cubicle in the Metropolitan Building at 10162 101st Street. The landmark sign, counters and some of the old fixtures went with it, but the spirit of the old place didn’t.

Ruth Michaels told a Journal reporter that it was too bad the old store had to close. “I suppose it’s one of those things called progress,” she said at the time from her retirement home in Hollywood, Florida. “Sometimes I wondered how the place has stood up this long.” She said the secret to the success and the longevity was “simply because we gave personal attention to the individual. Johnny knew practically everyone personally.”

The store returned to Jasper Avenue in January 1983 in the Melton Building at 103rd Street, and then moved again to a retail frontage at 10119 101 Street. But business continued to drop, and the end came in April 1986. Wire and wooden display fixtures were hauled out, and Mike’s closed its doors for good.

The landmark sign, which had long outlasted the Toronto Star Weekly it advertised, was donated to Fort Edmonton Park and stored at the city’s artifact centre for the next 25 years. It was restored by New Look Signs and returned to a place of pride on the street in 2014.

© Lawrence Herzog 2015