Every summer since I was a kid, my dad and I would take road trips across Alberta. It became an annual summer vacation in which he shared stories of the bridges he built in his career as a part of the Alberta Public Service. Having been raised in India, he is a colourful storyteller. The pride is evident in his voice in the way he describes bridges as a curve in the road or a span over a river. As I grew up the journeys continued, and now he takes my kids too, sharing his legacy as a civil engineer. These bridges remain as monuments across the prairie province, connecting communities not just through concrete and steel, but through care, service, and memory.

Canada’s labour migration is often narrated through the lens of economic contribution: newcomers as workers filling gaps in the labour market, contributing to GDP, or bringing “skills” to receiving societies. Yet this framing overlooks the full scope of labour that immigrants undertake, both formal and informal, as they rebuild their lives in new contexts. Migration is rarely just about moving from one place to another; it is a process of reconstruction: of identities, of homes, of communities, and often, of entire cities. This labour extends far beyond the economic, encompassing the often invisible and undervalued social labour required to create community, sustain cultural continuity, and foster mutual care in settler-colonial contexts like Canada. The story of Dilip Dasmohapatra, an Edmonton-based civil engineer and long-time community organizer, exemplifies this broader understanding of migration. His is a YEG origin story of building bridges literally, through infrastructure across Alberta, and socially, by helping lay the foundations for Edmonton’s South Asian community.

History & Migration

Dilip was born in 1944, during the end of the Bengal Famine in British India.[1] His early years were shaped by scarcity and struggle, but also by the determination of his family to pursue education as a path to stability. After earning his degree in Civil Engineering from Calcutta University, Dilip joined India’s Military Engineering Service (MES), where he designed and constructed infrastructure across the country including significant public projects like the Port Blair Naval Base wharf in the remote Andaman Islands.

This work trained him in the material reality of nation-building, but it was the chance to migrate that offered new possibilities. In 1969, Dilip arrived in Canada, part of a wave of South Asian immigrants who arrived after the exclusionary immigration policies based on race were lifted in 1962.[2] He faced many obstacles in moving from Andaman to Edmonton. Arriving in Canada at this time meant confronting the labour barriers that awaited newcomers in a still deeply Eurocentric Canadian workforce.

When my dad first arrived in Edmonton, he noticed everything – not just the skyline, but the specifics that most people might overlook. He recalled that Edmonton was a small city then, with fewer than half as many people.[3] The Royal Bank building on Jasper Avenue and 101 St, since torn down, was the tallest structure in its vicinity.[4] He noted the Le Marchand Mansion could be seen clearly from the south side. He even remembered the exact prices of things: a 1,200 sq. ft. bungalow cost around $14,000 to $16,000, rent for a two-bedroom apartment was $110 per month, and gas was $0.25 per imperial gallon, it cost just $4 to fill up a tank. A full-time professor’s annual salary was $15,000.

What makes these observations “signature Dilip” is the way they reflect his deep curiosity, attentiveness, and long view of the world around him. He has always paid attention to the small details that speak to larger patterns economic trends, urban development, and social change. He sees cities not just as places, but as systems. Growing up, I came to see how his mind worked: curious, reflective, and strategic. These are the qualities he passed on to me not through lectures, but through his way of moving through the world. He taught me that noticing things matters. That the shape of a building, the cost of rent, or the direction or name of a street can all tell you something about who we are, what we value, and how we live together.

Engineering Alberta: Labour on the Land

Dilip enrolled as a graduate student at the University of Alberta, where he completed a Master of Science in Engineering in 1972. During his time at the university, he was an active member of the India Students’ Association. The association organized community events, including Bollywood film screenings on Saturday evenings, which were held at the Physics Building and the Tory Turtle. At the time, the South Asian population residing north of Red Deer was estimated to be approximately 1,500.[5]

In the early 1970s, despite his qualifications and professional experience, Dilip found it difficult to secure engineering work in Edmonton. Racial discrimination impacted his career trajectory despite the fact that he had completed his master’s in engineering at the University of Alberta. In his first opportunity at the Government of Alberta, he was told by senior management on the hiring committee that “they do not hire East Indians”.

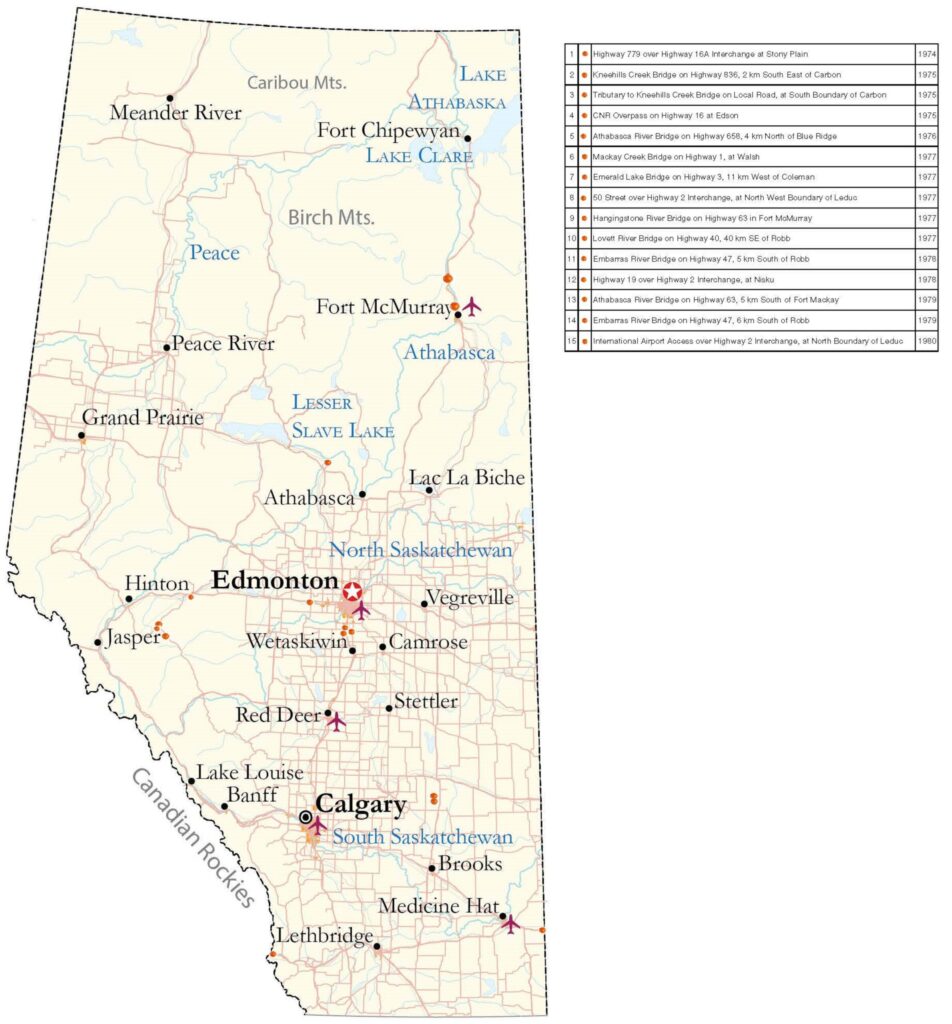

In 1973, his perseverance paid off: he was hired by Alberta Transportation as a Bridge Design Engineer. This marked the beginning of nearly four decades of contribution to Alberta’s physical landscape. Dilip was part of the workforce responsible for designing highway bridges and overpasses, playing a direct role in connecting the province’s growing urban centers and rural communities. He designed and managed projects like the Highway 779 over Highway 16A Interchange at Stony Plain and the Athabasca River Bridge on Highway 63 (5 km South of Fort McKay).

His labour, both intellectual and practical, shaped the infrastructure that Albertans rely on every day.

Building Community: Voluntary Labour and Collective Care

Dilip’s labour did not end when he clocked out of his engineering office. As a new immigrant in the 1970s, he experienced firsthand the isolation and dislocation that many South Asians felt in Edmonton. Rather than accept this as inevitable, Dilip, like many of his peers, set about organizing spaces for cultural connection and collective support.

In 1976, Dilip became one of the founding members of the Council of India Societies of Edmonton (CISE), an umbrella organization that helped unite Edmonton’s growing and diverse Indo-Canadian community. This work, from coordinating cultural celebrations like India’s Independence Day to advocating for newcomer support services, was rooted in the same principles that defined his engineering career: laying foundations, connecting people, and solving problems.

In the years that followed, Dilip also supported the creation of other community institutions like the Edmonton Bengali Association and Image India. He helped organize Diwali, Durga Pooja celebrations, and other events that brought together Edmonton’s South Asian families. His volunteer labour extended to logistical tasks like organizing functions at venues such as community league halls, collecting donations, cooking rasgullas and, more importantly, nurturing relationships.

Labour, Place, and Belonging

By the time he retired in 2011, Dilip had spent nearly four decades as a professional engineer with the Province of Alberta, a career that required technical skill, dedication, and resilience in a workplace where few South Asians were present early on. He had spent those same years working to ensure that future generations of South Asians in Edmonton would have a community to belong to, one that would recognize and celebrate their cultural heritage.

Legacy of Labour

Today, the organizations Dilip helped establish including CISE and the Edmonton Bengali Association remain active and important hubs for South Asian Edmontonians. CISE is celebrating its 50th year anniversary in 2026 and an official record of CISE has been filed in the City of Edmonton Archives in 2025. This is one of the first South Asian organization fonds that have been formally inducted in the City of Edmonton Archives. Dilip’s story is a reminder that bridging Alberta is not a passive process. It requires work: in workplaces, on construction sites, in kitchens, in community halls, and in conversations. Dilip has spent more of his life in Edmonton than in India. For my dad, the bridges he built were more than concrete and steel, they were pathways to belonging, for himself and for others.

[1] Anjali Bhayana, “Malnourishment by Design,” Healthy Debate, September 21, 2022, https://healthydebate.ca/2022/09/topic/malnourishment-by-design/

[2] Paula Simons and Clare Clancy, “On point: Fifty years ago, Canada changed its immigration rules and in doing so changed the face of this country,” Edmonton Journal, June 29, 2017, https://edmontonjournal.com/news/insight/on-point-fifty-years-ago-canada-changed-its-immigration-rules-and-in-doing-so-changed-the-face-of-this-country; Ida Beltran Lucila, “Filipino Pioneers of Edmonton,” Edmonton City as Museum Project, June 29, 2022, https://citymuseumedmonton.ca/2022/06/29/filipino-pioneers-of-edmonton/; Jeannette Austin-Odina, “Once a Teacher, Always a Teacher,” Edmonton City as Museum Project, August 30, 2021, https://citymuseumedmonton.ca/2021/08/30/once-a-teacher-always-a-teacher/.

[3] City of Edmonton. Population History. Edmonton, Alberta. [Accessed August 26, 2025] https://www.edmonton.ca/city_government/facts_figures/population-history

[4] “Royal Bank Building To Open Officially At Ceremony Friday,” Edmonton Journal, February 11, 1965, Newspapers.com.

[5] Province-level data is available in Statistics Canada, 1971 Census of Canada, Population Ethnic Groups, Table 2: Population by Ethnic Group and Sex for Canada and Provinces, 1971. Catalogue Number 92-723 in Statistics Canada [database online]. 2003. https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2017/statcan/CS92-723-1971.pdf Accessed August 22, 2025.