NOTE: this article contains historical but outdated and offensive language related to mental illness and neurodiversity.

Leilani Muir was born in Calgary on July 15, 1944 and grew up in rural central Alberta.

“Unloved, unwanted,”[1] Leilani was abused by her mother and called Tom or Marie rather than her real name.[2] In 1955, Leilani’s mother admitted her to the Provincial Training School for Mental Defectives (PTS) in Red Deer, later known as the Michener Center. A precondition was consent permitting sterilization, which Leilani’s mother gave.

Initially, no IQ test was administered; on the contrary, Leilani’s admission form included the words “seems intelligent,”[3] and one of the physicians suggested she suffered from emotional abuse rather than mental deficiency.[4] It was at the PTS that Leilani first learned her real name.[5] Leilani did well in school at the PTS.

Yet in 1957, following an eventual IQ test, the Eugenics Board declared her a “mental defective moron” and ordered her sterilization. In 1959, Leilani underwent a bilateral salpingectomy (cutting of the fallopian tubes) and a “routine” appendectomy. Leilani was told only that she was having her appendix removed.[6]

Leilani’s sterilization occurred under the premise of Alberta’s Sexual Sterilization Act, yet her surgery did not even conform to its regulations. The Act had two preconditions for sterilization: the individual had to be facing discharge from the institution, and they had to be “at risk of passing their ‘defects’ on to offspring.”[7] In many cases, Leilani writes, “the Board…took the law into their own hands.”[8]

Leilani left the PTS in 1965, “against medical advice,” to begin an independent life.[9] Subsequent IQ tests showed her to be of normal intelligence.[10] She married and divorced twice, and after learning about her sterilization through a medical test, spent years trying to have the damage reversed.[11] She then hired two Edmonton lawyers, and in 1996 she became the first person to successfully sue the Alberta government for wrongful sterilization. She was awarded $740,780, plus $230,000 for legal costs. In her decision, Justice Joanne B. Veit stated that:

“The circumstances of Ms. Muir’s sterilization were so high-handed and so contemptuous of the statutory authority…and…so little respected Ms. Muir’s human dignity that the community’s, and the court’s sense of decency is offended.”[12]

Leilani’s case opened the door for similar class action lawsuits. By 1999, the province had paid $142 million in settlement costs to over 700 victims.[13] After her lawsuit, Leilani legally changed her last name to O’Malley, in an act, she said, to “claim [her] identity.”[14]

In 1996, Glynis Whiting directed a documentary for the National Film Board of Canada called The Sterilization of Leilani Muir. In 2012, MAA & PAA Theatre staged a play called Invisible Child: Leilani Muir and the Alberta Eugenics Board. In 2014, Leilani Muir published her autobiography, A Whisper Past: Childless After Eugenic Sterilization in Alberta.

Leilani Muir O’Malley died on March 14, 2016.

The Sexual Sterilization Act

Early twentieth-century politicians in Alberta clung to outdated notions of genetics to further the cause of eugenic sterilization.[15] After the United Farmers of Alberta party was elected in 1921, the United Farm Women’s Association, concerned with “feeble-mindedness” in immigrants and accustomed to selective breeding of livestock on farms, “lobbied hard for a sterilization law.”[16]

The Sexual Sterilization Act became law in 1928. It was governed by a four-person Eugenics Board who made decisions on the sterilization of inmates in provincial mental hospitals and signed approval of each procedure. Five years later, Germany also implemented a eugenics policy.[17]

As Dr. Rob Wilson notes, “Most other jurisdictions, when they recognized the atrocities associated with the Nazi regime in the name of eugenics, backed off…. But in Alberta, the rates of sterilization seemed to just roll on.” Muir says that when Canadians heard her story, they were shocked. “People thought things like this only happened in other countries, or during Hitler’s time, but almost no one expected to read similar stories about our own country.”[19]

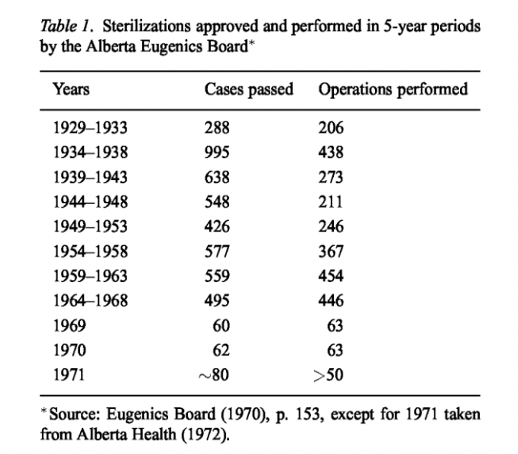

In 1937, the requirement of consent for sterilization was removed. This amendment “made virtually every inmate of Alberta mental institutions vulnerable to sterilization.” The Eugenics Board authorized the sterilization of 2,832 individuals.[21]

Sterilizations Approved and Performed by the Eugenics Board.

“Leilani Muir Versus the Philosopher King: Eugenics on Trial in Alberta” p. 188.

The Act tended to “single out people…who lacked power. There were more women than men…more people living in rural than urban centres…more persons of East European and Indian and Metis origin; people who were immigrants to the society…. It was the most vulnerable people who were dealt with under this statute.”[22]

The Sexual Sterilization Act was finally repealed in 1972 by Peter Lougheed’s provincial government.

University of Alberta’s Ties

The University of Alberta was implicated in the eugenics program. Board members were nominated by the university Senate, and president R.C. Wallace urged “that the time had come ‘to make eugenics not only a scientific philosophy but in very truth a religion.’”[23]

John MacEachran, founder of the Departments of Philosophy and Psychology and the University’s first provost, served as chair of the Eugenics Board from 1929 to 1965[24] and signed approval for Leilani’s sterilization.[25] After MacEachran’s retirement, the Departments of Philosophy, Psychology, and Education offered awards in his name. When MacEachran died in 1971, the Department of Psychology began the MacEachran Memorial Lecture Series.

Margaret W. Thompson, professor of genetics (who later worked at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto and received the Order of Canada), also served on the Eugenics Board and testified at Leilani Muir’s trial. At the trial, she wrongly claimed that heredity is the “overwhelming factor” in determining intelligence[26] and admitted that the board also took it upon themselves to approve sterilization of those they thought incapable of “intelligent parenthood.”[27] While the Advisory Council of the Order of Canada received a petition to revoke Dr. Thompson’s appointment, they declined to do so.[28]

In 1998, after Leilani Muir’s lawsuit, a Department of Philosophy committee formed to examine MacEachran’s involvement with the Eugenics Board. The committee determined that the board “acted unethically and unprofessionally not only by the standards of the present but by the standards of its own time” and recommended that the department cease awarding honours in MacEachran’s name.[29]

The Famous Five

Also implicated in the Alberta eugenics movement were the “Famous Five,” who helped garner “personhood” status for white and Black women in Canada in 1916[30]. These women were Louise McKinney, Henrietta Muir Edwards (no apparent relation to Leilani Muir), Irene Parlby, Emily Murphy, and Nellie McClung.

Murphy argued “that mentally defective children are ‘a menace to society, and an enormous cost to the state’” and that “‘mental defectiveness is a transmittable hereditary condition.’”[31] The Famous Five are celebrated in Canadian history, and parks in Edmonton’s river valley are named after them.

Leilani Muir Foot Bridge

In 2011, the footbridge crossing the North Saskatchewan River between Louise McKinney Park and Henrietta Muir Edwards Park was informally named the Leilani Muir Foot Bridge in a Works Festival project. Small plaques were affixed to the railings and remained there until 2016.

During the intense public effort I helped lead to save this footbridge, also known as the Cloverdale footbridge, from demolition for an LRT bridge, Lou Morin, who had helped Leilani write her book, contacted me to ensure I knew Leilani’s story.

The footbridge was demolished in December 2016, nine months after Leilani Muir’s death.

After the LRT bridge construction was completed and the area reopened to the public without reference to Leilani Muir, the Riverdale Community League and I coordinated the placement of a memorial bench in Louise McKinney Park. It is made with wood from the original footbridge and affixed with a plaque commemorating Leilani Muir and her connection to this place.

Note: As of date of publication of this article, the bench is still undergoing approval and construction. Hopefully it will be in place in later 2023.

References & Resources for further reading

“The Role of Oral History in Surviving a Eugenic Past.” In Beyond Testimony and Trauma: Oral History in the Aftermath of Mass Violence. Ed. Steven High. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2015. 119-38. Print.

Alberta Association for Community Living. Hear My Voice: Stories Told by Albertans with Developmental Disabilities Who Were Once Institutionalized. Saskatoon: Houghton Boston, 2006. Print.

[13] CBC News. “Alberta Apologizes for Forced Sterilization.” CBC News. Nov. 9, 1999. Online. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/alberta-apologizes-for-forced-sterilization-1.169579.

[12] Court of Queen’s Bench of Alberta. Muir v Alberta. 1996. Online. https://www.canlii.org/en/ab/abqb/doc/1996/1996canlii7287/1996canlii7287.pdf.

Department of Psychology, University of Alberta. “Department of Psychology MacEachran Statement July 28, 2021.” Online. https://www.ualberta.ca/psychology/about-us/edi-in-psychology.html.

Devereaux, Cecily. Growing a Race: Nellie L. McClung and the Fiction of Eugenic Feminism. Montreal: McGill Queens University Press, 2005. Print.

Dyck, Erika. Facing Eugenics: Reproduction, Sterilization, and the Politics of Choice. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2013. Print.

[30] Asian women and men were not allowed to vote in Canada until 1948, and Indigenous women in Canada were not allowed to vote until the 1960s.

Elections Canada. “A Brief History of Federal Voting Rights in Canada.” Online. https://electionsanddemocracy.ca/voting-rights-through-time-0/brief-history-federal-voting-rights-canada.

Eugenics Archives. N.D. Online. https://eugenicsarchive.ca/.

Gibbons, S.R. “‘Our Power to Remodel Civilization’: The Development of Eugenic Feminism in Alberta, 1909- 1921.” Canadian Bulletin of Medical History 31:1 (2014): 123-42. Print.

Grekul, J., Krahn, H., & Odynak, D. “Sterilizing the ‘Feeble-Minded’: Eugenics in Alberta, Canada, 1929-1972.” Journal of Historical Sociology 17 (2004): 358-384. Print.

[7], [29] On July 28, 2021 (amidst protests against the killing of George Floyd in the United States), the Department of Psychology’s Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion Working Group posted a link to the MacEachran Report on its website and stated that “[t]he PEDIWG endorses the Report of the MacEachran Subcommittee in full, condemns eugenics and other racist and discriminatory ideas, and opposes the use of psychology to promote racist and discriminatory practices.”

MacEacheran Subcommittee. “Report of the MacEachran Subcommittee, Department of Philosophy, University of Alberta.” April 1998. Online. https://www.ualberta.ca/philosophy/media-library/maceachran_report.pdf.

Malacrida, Claudia. A Special Hell. Institutional Life in Alberta’s Eugenic Years. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2015. Print.

McLaren, Angus. Our Own Master Race: Eugenics in Canada,1885-1945. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1990. Print.

McWhirter, K. G., and J. Weijer. “The Alberta Sterilization Act: A Genetic Critique.” The University of Toronto Law Journal 19:3 (1969): 424–31. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/825049.

[18] Miller, Jordan, Nicola Fairbrother, and Rob Wilson, producers. Surviving Eugenics. 2015. Online. https://eugenicsarchive.ca/film/

[1], [2], [3], [5], [8], [14], [19], [25], [26], [27], [28]

[27]Thompson also encouraged experiments on the testes of Down’s Syndrome boys.

Muir, Leilani. A Whisper Past: Childless after Eugenic Sterilization in Alberta. Victoria: Friesen Press, 2014. Print.

Stahnisch, Frank W. and Erna Kurbegović, eds. Psychiatry and the Legacies of Eugenics: Historical Studies of Alberta and Beyond. Athabasca: Athabasca U.P.,2020.

Stote, Karen. An Act of Genocide, Colonialism and the Sterilization of Aboriginal Women. Black Point: Fernwood, 2015.

[4], [6], [10], [11], [15], [20], [21], [24], [31] Wahlsten, Douglas. “Leilani Muir Versus the Philosopher King: Eugenics on Trial in Alberta.” Genetica 99 (1997): 185–198. https://doi-org.login.ezproxy.library.ualberta.ca/10.1023/A:1018370806190.

[16], [17], [22], Whiting, Glynis. The Sterilization of Leilani Muir. National Film Board. 1996. Online. https://www.nfb.ca/film/sterilization_of_leilani_muir/

Wilson, Robert A. The Eugenic Mind Project. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2017. Print.