In its 1966 annual report, the City of Edmonton Parks and Recreation Department described its purpose as facilitating “the development of the physical and mental well-being of all segments of the population of Edmonton during their leisure time.”

That same year, the city launched the Green Shack program, a still running free public recreational program that offers kids across Edmonton games, crafts, special programming and summer fun run by city staff. At the launch, 90 playgrounds had shacks running– a number that’s grown to 236 today sprinkled across the ballooning city boundaries.

With a bright blue uniform and first aid training, I was placed in Glengarry, a northside neighborhood park near an aging mall surrounded by schools. The park’s mature trees and vast playground layout made it bigger than most in town and brought an influx of families to visit, but what attracted most people was the water play feature. Three large concrete disks shot pressurized water into the air that fueled constant play, despite the dangers present for anyone unfortunate enough to fall onto the jagged surface.

Park programs are typically run with two Green Shack leaders who plan and offer a wide range of activities that anyone can access for free. As staff, we’d pour all the passion and excitement we could into planned theme weeks, sports tournaments and daily rituals for kids at the shack because we knew that every little effort spent to provide space for recreation meant a lot for the families and community we served. To generations of Edmontonians, the Green Shacks meant many things.

Crafts born out of creative impulse and cost, like 2-litre pop bottle rocket ship models or custom superhero playing cards let the hours fly by on endless summer nights. These are memories that live alongside loud cheering during ball hockey and soccer that was jokingly mandatory in an attempt to increase participation and involve kids who maybe couldn’t stand sports but enjoyed the Green Shack. Competitive four square was an especially popular game to burn time on long summer days, kids loudly smacking down large artificial dodgeballs into an opponent’s space for the winners to take home the coveted prize of daily bragging rights.

Photo supplied by author, Oumar Salifou.

My work in Edmonton’s downtown core at Central McDougall and Queen Mary parks, which are both nestled between communities full of hubbub, was illuminating. There was never a shortage of people: from large families with strollers and pets in tow, to homeless neighbours who used facilities near the playground to wash their hair, refresh and rest, and older couples passing by along their routine daily walk. Nowhere did it seem like the work we did at the Green Shack was more valued than in the downtown core; with an endless influx of kids and families, the shacks meant so much to the community.

Community

When I started a search for a better overview of Green Shack history in Edmonton, there wasn’t a definitive book or article that summarized or connected the program’s decades of history. What did arise was several stories throughout the years that speak to the shack’s impact, survival and the character of neighborhoods that house the program.

A Green Shack in the neighborhood of Athlone in 2018 suffered a devastating break-in that wiped out almost all supplies, one day before summer programs were slated to start. The response from community members was fast, coming together to gather needed supplies and donations so the shack could continue to operate and serve Athlone families. This testimonial to the localized value and love, as well as need, for community gather spaces, youth programming, and recreational activities.

Back in 2014, I split my work at the shack between two parks: mornings at Queen Mary and afternoons at Central McDougall because budget cuts threatened the existence of the Green Shack.

The crisis was sparked when the provincial government cut $275,000 from a jobs program that helped the city hire season park staff.

Cuts were about to be made to reduce shack hours and remove the program from unpopular park locations, but community members voiced their opposition which led to city council covering the budget shortfall with support from over 100 community organizations.

Green Shack supporters across the city, wrote passionate letters in the Edmonton Journal about the importance of shacks for neighborhood kids in a time where the responsibility for funding was neglected by several levels of government.

(Edmonton Journal, 2013. Image courtesy of newspapers.com archive)

Not Just a Wooden Shack

Earlier iterations of playground programs fluctuated how many parks received services which points to potential budget struggles throughout the history of Green Shacks. In 1977, Green Shacks only ran at 23 locations. Almost a century of Green Shacks is a testament to the communities that have fought to preserve free recreational services given the constant threats to the access and existence of programming.

Not always run during summer, in 2007 the city introduced Snow Shacks, a program based on the Green Shack concept but to combat the sometimes empty or boring holiday break and provide outdoor activities for kids during the winter.

For years after my time working at the shack I’d still regularly meet people who’ve grown up in Edmonton that have some personal memory of the program. In one instance a colleague confessed that he would visit the shack regularly to torment the assigned staff with pranks and other childish jabs with his siblings.

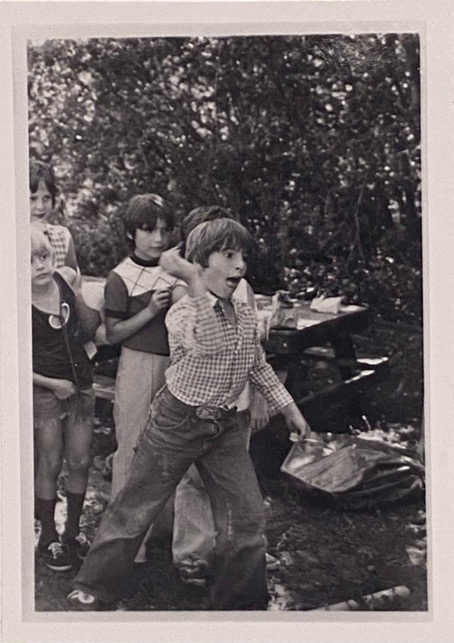

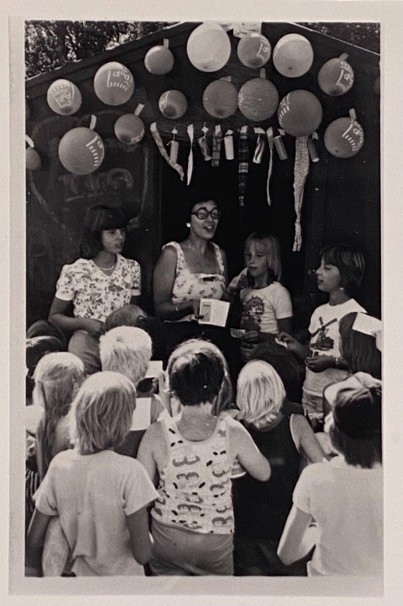

The amount of anecdotal and community hearsay about the Green Shack is in stark contrast to the available official histories and stories about the recreational service. Several department reports and news stories reveal some information, but the most abundant “official” resources are several early photos of park activities when the service initially launched.

Photos found in the City of Edmonton archives of shack activity during the 1960s are nostalgic depictions of joyous times that depict a variety of activities that haven’t changed. Attentive kids stand at the front of a shack waiting for instructions for the next activity.

Here, in the green spaces and neighbourhoods, we can’t help but be reminded that amiskwaciwâskahikan has been home to diverse Indigenous communities since time immemorial, their presence and stewardship stretches past settler history but also beyond our sometimes totalizing settler views about what community and relationship building mean in practice.

Based on these photos you might conclude that 1960s Edmonton was largely a homogeneous and white place; while that was true in some ways it also smothers historic realities at play like growing immigration and Indigenous claims to life on this land. These are complexities for myself and many in similar diasporic, culturally diverse, and ethno-racial communities across Edmonton, Alberta, and Canada.

Making new meanings in shared spaces

Near the end of my time working at parks I had an experience that typified the value and meaning that green shacks created for communities. I was at Glengarry park and a new group of kids asked me for painting supplies we kept on the highest shelf inside to delay the inevitable disaster of paint sprayed across every surface.

To prepare, I gave strict instructions that only the shack could be painted with a limited supply to minimize stains. Two of the kids focused on a corner to start plotting how to draw an image that wasn’t clear to me at first.

They painted with delicate attention and strict lines: Filled in lines with green, red, and bright white. By the time they were finished, an entire park bench and most of the green metal siding was coloured in paint. Most of the painting (and some mess for me to clean up) was done in the signature abstract style of 7-year-old kids. Looking back over to the corner of the shack, what immediately stood out were painted flags that I didn’t recognize at the time, but now know that they were depictions of the Palestinian flag.

The fact that a service as unassuming as the Green Shack was able to house so many meaningful experiences for me speaks to how far even a small amount of intention towards community building can go. Colonialism in amiskwaciwâskahikan and Palestine has suppressed cultural traditions, symbols and practices that form Indigenous identity on those lands: learning about these complexities and how to share and participate in everyday culture and community is something that was and still is threatened.

I reflect now on those moments and am finding a deeper meaning to the flags I saw that day.

Decorating the shack with paint was a necessary ritual when I worked for the program and a practice as old as the program’s origins in the 1960s. Edmontonians across the city of all ages remember and may reflect on memories and moments of place-making in little spaces, like their local park, their playground, and their neighbourhood Green Shacks. Countlessly paint, repainted, built, and rebuilt, through the years.

Whether or not documentation of community voices, youth memories, and diverse histories revolving around the Green Shacks have included the presence of diverse Peoples or knowledge does not erase the outlasting and ongoing contribution of our interlinked presence and knowledge. The growth of Edmonton as an urban centre through the last century and a half, only continues on. The layers of what our neighbourhoods, communities, and settlement history of this city means, starts in the smallest corners.

Oumar Salifou (2022).

What does the Green Shack mean for you?