In 2018, a new Edmonton park was opened and given the name “ᐄᓃᐤ (ÎNÎW) River Lot 11∞,” an appellation that evokes a variety of aspects of Edmonton’s history. One such aspect that many Edmontonians may not have known about, given their lack of memorialization until this park’s construction, are the river lots that once characterized much of the land in present-day central and eastern Edmonton. Originally farmed primarily by Métis people, the shape of these lots influenced the form of our city’s urban landscape, and the names of one-time owners – Fraser, Garneau, Groat – provide appellations for neighborhoods, roads, and other Edmonton landmarks. While many were sold as early as the late-nineteenth century and subdivided for urban development, in other cases, they would remain farmland until well into the 1950s, testifying to the dramatic changes the land now called Edmonton has gone through.

A marker at the entry of ᐄᓃᐤ (ÎNÎW) River Lot 11∞ Indigenous Art Park. Photo courtesy of the ECAMP Team, August 2020.

“iskotew” by Amy Malbeuf is one of the installations at ᐄᓃᐤ (ÎNÎW) River Lot 11∞ Indigenous Art Park. It “spells word “fire” in nehiyawewin syllabics. Photo courtesy of the ECAMP Team, August 2020.

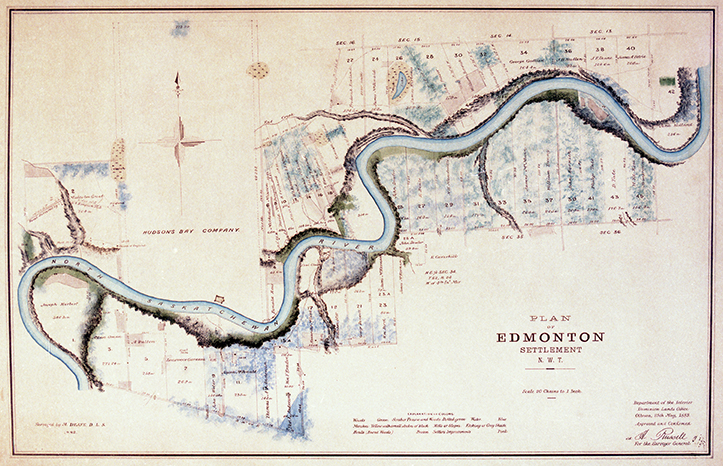

As the area’s fur trade was winding down, farming began to take on a greater importance in the lives of the people around Fort Edmonton. Many began staking claims to land in the Fort’s immediate vicinity, farming in a river lot fashion. A staple of Métis culture, this style of farming allowed for access to the river, wooded areas, cultivated land, and provided space for hay lands as well. While a rough (and unapproved) survey was undertaken by government surveyor W. F. King 1878, a more thorough government-approved survey in 1882 formalized the division of the land in terms of a river lot pattern, which is what the predominantly Métis population in the area at the time desired. The survey created 44 large lots across the banks of the North Saskatchewan, most of which stretched east of the Hudson’s Bay Company reserve lands. In many ways, the early history of these river lots is a history of the Métis and their kinship networks – marriage between the area’s families was common, as were friendship and support systems.

Image courtesy of the City of Edmonton Archives EAM-85.

The even-numbered lots on the north side of the river (the lots on the south side had odd numbers) were initially owned primarily by former Hudson’s Bay employees, and the distinctive survey was a result of the Hudson’s Bay reserve lands (see photo above). As Jan Olson notes in Scona Lives, there was a distinction between the histories of the north and south side river lots – those living on the north side of the river usually had closer relationships to HBC officers, and whatever land disputes there were (and there were land disputes!), the land rights of settled Métis families there were generally quite secure. On the river’s south side, however, issues relating to the land were at times more fraught, especially given the entanglements with the Papaschase Cree who lived in the area, some of whose members settled on these river lots and intermarried with Métis families.

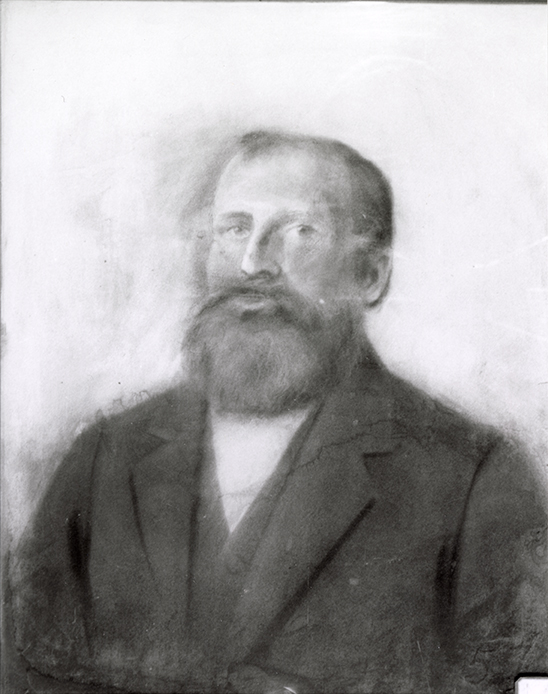

One south side river lot owner who lived relatively peacefully was Joseph McDonald, a Métis homesteader who settled on what became River Lot 11 (which, today, would be bounded by roughly 106th street and Calgary Trail). McDonald had a long familial history in the area – his father, Donald McDonald, worked as a steersman at Fort Edmonton before eventually moving to Red River, where Joseph was born. Joseph McDonald began homesteading on this land in 1878, apparently by an agreement personally made with the Papaschase Cree. According to a newspaper biography of him, he traded a gun and, with some other considerations, concluded this arrangement with the band. A similar understanding allowed Laurent Garneau to settle his nearby river lot, number 7 (from present-day 112th to 109thSt.), and indeed, the relationship between the Garneau family and Chief Papaschase was very close. When, in 1885, Garneau was imprisoned for his previous involvements with Louis Riel, Papaschase personally took care of Garneau’s family.

Sketch of Joe McDonald, 1890. Artist unknown. Photo courtesy of the City of Edmonton Archives EA-10-2972.

Portrait of Garneau family, c. 1910. Back row – Larry, Louis, Victoria, Alex, Charolotte, Archangel Front row – Edward (Ned), Eleanor (Mother), Millie, John, Laurent (Father). Photo courtesy of the City of Edmonton Archives EA-58-4.

Other south side families faced struggles relating to their Indigenous identities, especially with the pressures of Métis scrip and the 1885 rebellion – Métis scrip was a one-time payment of either money or land that, in the eyes of the Canadian government, extinguished the person’s Indigenous land rights. Scrip was notorious for its convoluted process and unethical nature. Many families on these south-side river lot farms, including the family of William Meaver on River Lot 15 (bounded by present-day 99th St. to 101 St.), Charles Gauthier and his son on River Lot 17 south (99th St. and Mill Creek Ravine), George Donald and Betsy Brass of River Lot 21 (91st to 95th St., in the present-day Bonnie Doon neighborhood), took scrip. Some of the families that were members of the Papaschase band either took scrip (as Brass herself, who was a woman of mixed Cree/Saulteaux ancestry did), or joined the Enoch band, as William Ward’s family (of River Lot 13) did. As settlement increased, many Métis families of this period would leave to places such as St. Paul des Métis, St. Albert, Tofield, and Cooking Lake.

Clockwise from left: 1) Driscoll and Knight Map of the City of Edmonton 1912. Image courtesy of the City of Edmonton Archives EAM-78. 2) An altered magnification of the Plan of Edmonton Settlement circa 1882 to highlight river lots 6 to 20. 3) A magnification of the Driscoll and Knight Map of the City of Edmonton 1912 to highlight the McCauley neighbourhood. Image courtesy of the City of Edmonton Archives EAM-85.

After the river lots were surveyed, some of this land was rapidly swallowed up by Edmonton’s rapid growth. Sparked by the Hudson’s Bay Company subdividing and selling off the lands of its reserve, this was especially true on the north side of the river, where Edmonton’s subdivision and neighborhood development had, by 1912, converted most of the land to urban spaces. Aspects of the river lot survey itself can still be seen today: for example, the unusual angle of the McCauley neighborhood is a result of how river lots 6 to 20 were surveyed, which abutted the old lands of the Hudson’s Bay Reserve; on the south side of the river, University Avenue’s unusual angle is also a product of this survey.

Right: An altered Google Maps image highlighting University Avenue. Image created by the ECAMP Team.

Land speculation and different timings of land sales and subdivisions made urban development a patchwork. On the south side of the river, as the Calgary & Edmonton Railway was being built at the start of the 1890s, subdivisions around these railway lines meant that the town grew with it and the owners that sold at this time became very wealthy. By the turn of the twentieth-century, many other river lots around present-day Old Strathcona began to become urbanized – River Lot 5 became the initial land grant for the University of Alberta, purchased in 1907 from Mrs. Annie Simpson and her daughter; at about the same time, River Lot 3, immediately west, was sold to a land development syndicate, which became the Windsor Park neighborhood. By 1928, almost all of Edmonton’s river lot farms had become urban land, neighborhoods which no longer saw livestock walking about them but instead thousands of settlers.

However, not all of the river lot farms had become urbanized land at this point in time – some of the farms in what is today south-east Edmonton would remain farmland until well into the 1950s. One river lot in which this was the case, and which also exemplifies the extensive American settlement that occurred in Alberta, is Daniel Webster Warner’s farm. Warner was raised in Iowa and would settle on River Lot 39 – at the heart of today’s Gold Bar neighborhood – in 1899. He cleared a reported 100,000 feet of lumber on this property, where a variety of crops were grown and livestock – notably, cattle and hogs – were kept. The Warner family built a large brick house on this property in 1913, which was known as the Gold Bar Farm. Warner became involved in politics as a United Farmers of Alberta MP, and participated in many farmer’s organizations.

Warner’s farm and neighbouring farms in what is today Edmonton’s east side were subdivided as early as 1912, but with a severe economic downturn the following year, the First World War, and then the Great Depression, it would not be until the 1950s that urban development actually occurred in this part of Edmonton. River lots neighboring the Gold Bar Farm, notably lots 35 and 37 to the west which were owned by Joseph M. Holt, were annexed by the City in 1954 and became the neighborhoods of Fulton Place and Capilano. In 1956, the Gold Bar Farm was also annexed by the City of Edmonton. Much of River Lot 43 to the east, meanwhile, became the Strathcona Refineries. With these annexations, the last of the southern river lot farms disappeared beneath urban development.

“ᐄᓃᐤ (ÎNÎW) River Lot 11∞ Indigenous Art Park, August 2020. Photo courtesy of the ECAMP Team.

View of the river valley from ᐄᓃᐤ (ÎNÎW) River Lot 11∞ Indigenous Art Park. Photo courtesy of the ECAMP Team.

“Preparing to Cross the Sacred River” by Marianne Nicolson. Photo courtesy of the ECAMP Team.

Of course, there are many other stories related to these river lots. Like Edmonton’s wider history, there are layers of stories that have too often been understood as separate narratives, but in fact can only be understood through their interrelation. The Edmontonian seeking a reminder of the old river lots and these different layers of history can find one just north of the Strathcona and Garneau neighborhoods at the place we started this story – ᐄᓃᐤ (ÎNÎW) River Lot 11∞. Here, one can quite directly experience this quality of the land now called Edmonton (but which, as this park reminds us, has many other names) – contemporary Indigenous art is spread throughout ÎNÎW Park, and the nehiyawak (Cree) word ÎNÎW means “I am of the Earth;” the name is also a reminder of Joseph McDonald and the river lot (11) that this land at one time was, as well as the history of Métis people in this place; trees briefly obscure and then reveal views of the City’s downtown as cars winding along the road provide an aural reminder of Edmonton’s rapid urbanization, and the settlement of peoples from different parts of the world here. The park demonstrates that these histories extend into the present and are interrelated to one another, intersecting, forming this place.

Connor Thompson © 2020

Suggested Reading

Gilpin, John F. “The Edmonton and District Settlers’ Rights Movement, 1880 to 1885” in Swords and Ploughshares: War and Agriculture in Western Canada ed. R. C. Macleod. Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 1993. 149–172.

Olson, Jan. Scona Lives: A History of River Lots 13, 15, and 17. Edmonton: Missy Publishing, 2016.

Trevor Donald, Dwayne. “Edmonton Pentimento: Re-Reading History in the Case of the Papaschase Cree” Journal of the Canadian Association for Curriculum Studies 2:1 (2004) 21–54.

Suggested Viewing

Matt Hiltermann, “Reading Métis History into the Landscape of Edmonton,” Edmonton City as Museum Project, June 25, 2020.