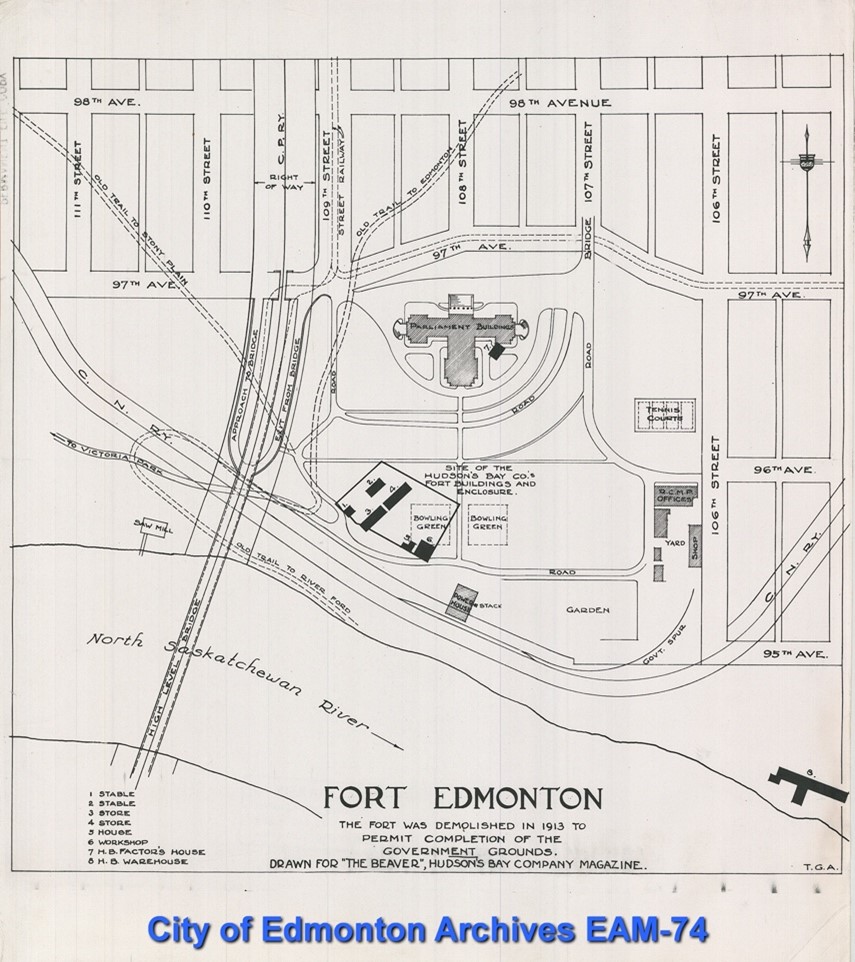

At the height of summer in 1838, Roman Catholic priests François Blanchet and Modeste Demers visited L’Fort des Prairies (Fort Edmonton) eliciting a wave of weddings and christenings. Marguerite’s sister Nancy (17) was married to Chief Trader J. E. Harriott who’d worked for their father over the years. With just Sophie (23), Marguerite (13) and little Adelaide (6) at home as Alexander was at medical school in Montreal and John Jr. was away working for the HBC, Louise had earned the luxury to simply enjoy all she had created. The servants stoked fires and set tables; the household mechanics worked with a clockwork efficiency. For teenaged Marguerite, it was a time to dream and consider her future. Of all the Rowand daughters, whose country marriages were bound by practicality or alliance, Marguerite may have been the first to truly choose her husband. Her father was made Councilor of Rupert’s Land in 1839, and he could have arranged any union she so desired. Instead, she waited, perhaps steadfast in the knowledge of her liberty of choice. Or perhaps she’d already chosen a certain young man attending the Academy at Red River, James McKay Junior – or as Marguerite called him, Jamie.

James McKay Senior was a Scottish born HBC steersman, his wife a Gladu born at Cumberland House. The McKays had been stationed at Fort Edmonton since 1818 and were kept on after the merger with NWC in 1821. James Jr. was born the winter after the flood. Marguerite and Jamie spent their infancy together, swaddled in pack-boards swinging from poplar limbs in the spring breeze. Jamie held space in Marguerite’s earliest memories.

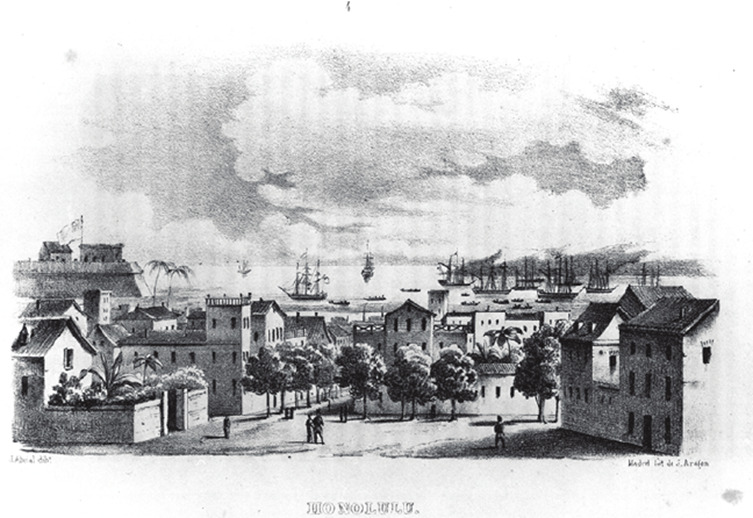

Nothing of much note occurred in Marguerite’s young life until the summer of 1841, when Governor Simpson travelled past on his ‘round the world tour’ funded by Queen Victoria. At the first invitation, John Rowand took his mighty leave for the Sandwich Islands. The party left Edmonton on July 28th, reaching Columbia River on August 20th and, department headquarters at Fort Vancouver five days after. From what would become Portland, they travelled by paddle-steamer (the Beaver) to Alaska then reversed down the coast to California, dillydallied in Monterey and enjoyed a Spanish ball in Santa Barbara. Once recovered of their revelries, Simpson and Rowand caught the Northeast trade wind on January 27, 1842, sailing into Honolulu harbor (Island of Oahu) on February 12th.

As representatives of the Imperial Crown, the ship’s passengers were welcomed by a throng of cheering locals. It seemed to Rowand the entire island attended their arrival. In re-telling the story to his children, he often remarked at the weight of the tropical air, how the succulent perfume of frangipani necklaces warmly bestowed upon each visitor would linger, clinging to the skin for days. The sounds of strange birds calling out uninhibited and the overwhelming multiplicity of greens washed upon the shore of Marguerite’s dreams ever after. Governor Simpson and the delegates enjoyed rooms at the royal palace in the cool uplands of Nuʻuanu Valley, a cluster of lofty thatch buildings, roofs edged with fern leaves. The main building had ceilings some 40 feet in height with a row of chandeliers suspended from the center-beam. John had never encountered such a fusion of culture and engineering, of tradition and innovation. In the days that followed, the group visited various plantations (salted fish, coffee, indigo, salt, sugar, and molasses were common exports) and stood atop Punchbowl Hill.

Marguerite loved her father’s tales of girls with flower crowns dancing in swaying skirts, about standing at the edge of an extinct volcano and, hearing whale-songs echoing from the channels between islands. In late March, John found himself in Lahaina (Island of Maui) with the envoy to King Kamehameha III where he was lavished with gifts of fragrant lei and a multitude of plaited grass baskets heaped with treasures of the coral isles: plaited smooth Makaloa mats, a collection of conch, several whale teeth and vertebra, a pouch of raw pearls from the oysters of Puʻuloa (Pearl Harbour), and some sticks of the increasingly rare Hawai’ian sandalwood. Simpson and his party languished at Kaniakapūpū, the King and Queen Kalama’s summer retreat, surrounded by members of Hawai’i’s alii, or ruling class families. John met the King’s nephews, Kamehameha IV, Kamehameha V and their little sister, Victoria Kamāmalu.

Hawai’i State Archive. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

The sounds of laughter and children’s voices must have drawn him homeward. Sunkissed and satiated, John Rowand set sail aboard the Vancouver in April 1843, aiming to be back for the start of another HBC year. Governor Simpson’s envoy would be instrumental advocates of Hawai’ian independence and the British and French governments formally recognized the Kingdom of Hawai’i on November 28, 1843. Now and again, Marguerite’s father would start his evening story, “when I was the Envoy Extraordinary with the Minister Plenipotentiary to your Majesty…” and everyone knew the yarn would be tropical, nautical, rolling with sea monsters and waves the height of the clouds.

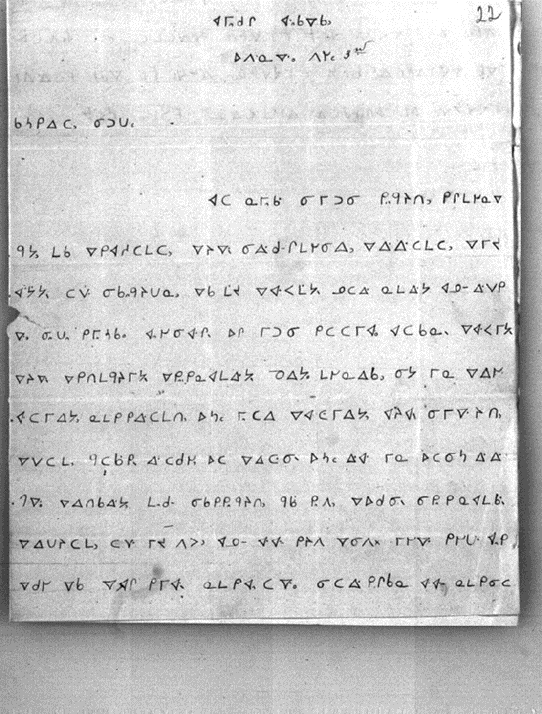

Chief Factor John Rowand returned to his family at Fort Edmonton, and a district rife with food shortages and the loss of horses from the harshest of winters. Temperatures had gone below minus fifty. Missionaries of every variety had also established themselves on the prairies. Despite having taught his daughters to write in syllabics, John was less than pleased to find Reverends James Evans and Robert Rundle still intruding, even faithfully, upon the Fort community. John felt too much time was taken up on faith and saw it as a distraction from work. At the behest of his most pious child, Rowand acquiesced, allowing the construction of a small chapel. Here, Sophie Rowand who could sing hymns like an angel, scratched out each and every syllabic of her ecclesiastical inquiries with the precision of a prayer.

“Although it is hopeful as we write to… also my younger sibling. But we are concerned (troubled) how we should say it to you. We are poor (unfortunate) we do not know very much here where I am. It is nice (good, beautiful) for me it is probably different how Kise’Manito (God) thinks about us, that is why we…”

It was also sister Sophie who convinced Marguerite to begin writing Jamie, as a way of practicing the fledgling Cree script. Early correspondences were simple descriptions of daily life at the Fort, the weather, about the abundance of hazelnuts and berries that year, and renderings of stories told by her father. Marguerite swiftly became an astute wordsmith, surpassing her sister in both speed and translation between Cree and other tongues. Each spring and fall, her letters to Jamie followed the rivers and cart trails they both knew so well, narrowing the leagues between them.

Census records of 1843 show that the McKay family had settled into farm life at Red River, James Sr. having retired a few years prior. Noted are two older sons and five more below 16 years, as well as two daughters. Jamie was still attending Red River Academy, but clearly had plans of his own. The era of old west fur traders and exploration was evolving into a new era of settlement and agriculture. For Jamie, the land was a greater force; it called him back at every instance. He preferred to ride and snowshoe, hunt and trap, often staying out along the Assiniboine for days unaccompanied – -a habit that vexed his mother terribly. What she didn’t understand, was that Jamie wasn’t ever truly alone. On the land, he saw the world through two sets of eyes, his own and that vision which he shared with Marguerite: a love of the land itself. The childhood sweethearts remembered a simpler time, when the animals were abundant, and communities weren’t strewn continent-wide. The bison population had slowly dwindled since the 1830s when the beaver ran out, other commercially viable animal populations were already diminished. Jamie understood this trajectory and so, he relished in the visages of a withering ecology. And always, after each foray, he tucked a letter into the mail packet of the next westbound brigade.

Early in 1847, Marguerite’s letter described a visit from artist, Paul Kane, and the wildfire skies, lit aglow with orange shimmer. She added her concerns about the river running low and put in writing her heartache over the Indians starving in their camps over winter. There was little pemmican to trade or share. The bison had largely abandoned their northern range, forcing the Crees to hunt further south. Conflict with the Blackfoot ensued. These were hungry, distrustful, desperate times. Marguerite held hope that her community would endure, but the loss of her mother in 1849 nearly sent her adrift. Louise Umphreville Rowand, matriarch and First Lady of the Fort had served the HBC with grace and compassion for four long decades.

After the funeral, John was quiet. Far too quiet. His daughters began to worry. Marguerite watched her father drown himself in his work. There was still some bison trade, and with cargo moving more by trail than by river, the logistics kept John Rowand’s head above water until July of the following year when his daughter Nancy died suddenly. Her children, ages 4 to 14, had lost their mother and grandmother. The waves of grief were unrelenting. It was Marguerite (23), Sophie (35), and Adelaide (17) who wiped tears and held little hearts in the flow. All the sorrow a river could contain sent on its path to the sea. In time, the currents became more navigable. Ripples of joy were felt across the ocean of ice and snow when John Jr. announced the birth of Adelaide II at Fort Pitt just before Christmas of 1852.

Tides were changing for Jamie, as well. Already an expert guide and interpreter he began working for HBC mid-season 1853 with postings at Swan River District, then Qu’Appelle Lakes and Fort Ellice in 1855 where the news of John Rowand’s passing set the Fort to stillness. He wrote Marguerite immediately, understanding the significance of the loss, offering to visit Edmonton at his earliest capacity. In the weeks following their father’s death, Marguerite and her sisters made arrangements to move east; John had willed his property at Red River to Marguerite and there was much to do beyond grieving. Intended as a space for John to retire, the two room, log-hewn cabin would be a marked adjustment from the Big House. With that in mind, Marguerite sent Jamie a fair-sized wooden box of items; a fine red shirt made of flannel, a pair of fur-trimmed moosehide gloves, a scrimshaw whale tooth, the horn of a bison polished to amber hues, feathers from a variety of birds tropical and otherwise, and John Rowand’s silver inkwell. She couldn’t think of anyone more suited to the gift.

Jenna Chalifoux © 2021

Further Reading and Sources

HAWAI’I (SANDWICH ISLANDS)

Mills, Peter. (2009). Folk Housing in the Middle of the Pacific: Architectural Lime, Creolized Ideologies, and Expressions of Power in Nineteenth-Century Hawaii. The Materiality of Individuality: Archaeological Studies of Individual Lives.

Daws, G. (1967). Honolulu in the 19th Century: Notes on the Emergence of Urban Society in Hawaii. The Journal of Pacific History, 2, 77–96. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25167896

HBC Sandwich Islands Miscellaneous Items 1834-1867

JAMES MCKAY

Metis Dictionary of Biography: Volume M

Manitoba Historical Society

James McKay Sr. HBC Service Record

PAUL KANE

MacLaren, I. S. (1989). “I Came to Rite Thare Portraits”: Paul Kane’s Journal of His Western Travels, 1846-1848. American Art Journal, 21(2), 7–4. https://doi.org/10.2307/1594539

SIR GEORGE SIMPSON

Letters of Sir George Simpson, 1841-1843. (1908). The American Historical Review, 14(1), 70–94. https://doi.org/10.2307/1834521