Disclaimer: Please note that this piece references anti-Black violence, brutality, and white supremacy. A reference to a specific act of anti-Black violence appears immediately after the back & white advertisement for the Harlem Chicken Inn.

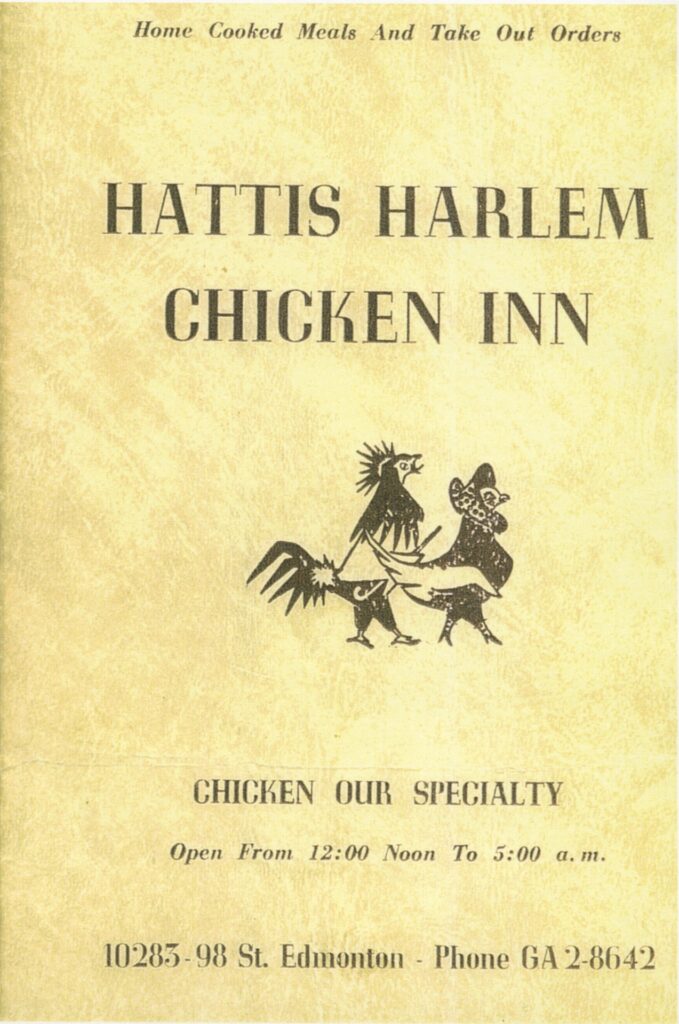

A brutalist hulk of a building occupies a landmark of Edmonton’s Black history. What is now a security post to the Court of Queen’s Bench was once the front door to Hatti’s Harlem Chicken Inn. Most folks who ate there, however, simply knew it as “Hattie’s place,” after its proprietor, Hattie Melton. The restaurant was a beacon for Southern and Soul food that attracted everyone from the Harlem Globetrotters to Mayor William Hawrelak. For a quarter century, Hatti’s was the city’s indispensable stop for African Americans visiting from the United States, as well as a career-starter for Black Edmontonians.

Melton’s life began with a series of hardships, first in Oklahoma and then in Amber Valley, Alberta. But before we delve into her remarkable life, it’s worth remarking how important foodways have been in maintaining Black culture. Afroculinaria writer and chef Michael Twitty has written that Southerners “use food to tell themselves who they are, tell others who they are, and to tell stories about where they’ve been.” Memory, celebration, mourning: all of these rites are marked with specific foodways.

In the case of Hattie Melton, many Southern staples were represented in her cooking, including corn fritters, barbecue, biscuits and gravy, and, most famously, fried chicken. These are labour-intensive foods when cooked from scratch. LeRoy Williams, Melton’s nephew, remembers frying the corn fritters. “The fritters were a signature,” Williams said. When other local restaurants noticed their popularity, they tried to duplicate the dish. But, according to Williams, “there was no comparison.”

Melton closely guarded her recipes, and for good reason. A series of chicken restaurants popped up in Edmonton in the 1960s, all attempting to copy Melton’s Southern fried style. Williams said that “Aunt Hatt”–as he affectionately calls her–had a sharp business acumen, yet also knew that she played an important role in providing work and food to the community. Dozens of Black Edmontonians counted on Melton for a job. At the Chicken Inn, the poor rubbed elbows with the rich; it might have been one of Edmonton’s only fully integrated spaces. It was also a gathering place for Edmonton’s biggest names in music, as Big Miller and Tommy Banks were both loyal customers.

Melton was born Hattie Robinson in Clearview, Oklahoma, in 1903. Her parents had come to Oklahoma–then called Indian Territory–from the Deep South as part of a movement to create a Black homeland for descendants of enslaved people.

Clearview was one of Indian Territory’s thriving Black townships, but Oklahoma statehood in 1907 spelled disaster. The same Jim Crow laws pushing African-Americans out of the Deep South were suddenly the law of the land in Oklahoma. In 1910, Oklahoma passed the “grandfather clause” into state law, making it nearly impossible for Blacks to vote. Oklahoma had the dubious distinction of being the only state to segregate phone booths.

A particularly brutal lynching in the nearby Okemah terrorized residents of Clearview. A mother and her 14-year-old son were hung from a bridge. Whites made postcards of the event and passed them out in Black townships. It was the final blow for many residents of Clearview. Hundreds of Black Oklahomans like Robinson’s family fled to Canada, where they were subjected to more indignities at the border. As more Blacks sought refuge in Canada, Canadian officials sought ways to block the migrants. Head taxes and arbitrary health inspections were imposed while, in Edmonton, leading citizens sought to exclude Black Americans.

Despite the hardships, new Black townships thrived. Hattie Robinson’s family moved to Amber Valley but, just when things appeared to be calming down, Robinson’s parents both fell dangerously ill. Robinson was sent away to Calgary as a teenager, where she boarded in a rooming house run by Peter Melton. Melton’s brother Bob had started a restaurant called the Chicken Inn, which catered to Black railroad workers. Author Cheryl Foggo wrote that the Chicken Inn was a “raucous place” with jazz, liquor, and dancing–and delicious food, of course.

Hattie Robinson married Peter Melton and started cooking at the Chicken Inn. The marriage to Melton proved difficult. Melton was remembered by Jimmy Melton as something of a solitary workaholic with a temper. At some point Hattie and her daughter Myrtle decided to leave Calgary, and head out for a new life in Edmonton where they moved into a modest brick bungalow east of downtown. The house still stands on 86 street, almost literally in the shadows of Commonwealth Stadium.

At the time, few professional opportunities were open to Black people in western Canada. Jobs on the railways and in meat-packing plants were common, but few entrepreneurs dared risk starting a business in Edmonton, which was known for its institutional racism. Even after the Ku Klux Klan’s influence had ebbed elsewhere in the 1920s, the organization remained powerful enough in Edmonton that in the 1930s, Mayor Dan Knott maintained a close and open relationship with the white supremacist organization. Many Black people lived near Borden Park, but had to endure segregation at the park’s pool, among other places.

To put all of this into context, Hattie Melton was a single Black woman opening a business on her own at a time when de-facto segregation was the norm and white supremacists dominated local politics. The deck was stacked against her. It is possible—the records are not clear—that she was the first Black woman to own her own business in the city. Melton started advertising in the Edmonton Journal in 1948, and quickly attracted a following. The influx of thousands of American soldiers provided a boost to the restaurant as well.

Southern food, as the food writer Michael Twitty states, is an umbrella term that includes soul food, and both were represented as Hatti’s. Hot tamales, corn fritters, and fried chicken provided a taste of home to Southerners.[1] Melton’s restaurant moved several times from the 1940s until the early 1970s, when it finally closed up shop. Each move represented a higher level of visibility for Melton and greater acceptance from white Edmonton. The last iteration of the Harlem Chicken Inn was located a block from City Hall, on the corner of 98 Street and 103 Avenue. LeRoy Williams remembers serving chicken to Mayor Hawrelak several times.

Taking a cue from Calgary’s Chicken Inn, Melton saw an opportunity to turn her place into a night spot as well as a restaurant. The centre of Black Edmonton’s social life was Shiloh Baptist Church, which hosted suppers, dances, and a variety of events apart from church services. As many African-American scholars have noted, the push and pull between the sacred and the secular is a hallmark of the Black American musical tradition. With Shiloh, Black Edmonton had the sacred; Hatti’s provided a public space for the secular—jazz, blues, and soul.

The hours of the restaurant attested to its popularity among city’s musicians and nightlife goers. For years, the restaurant’s hours of operation ran from noon to 5:00am.[2] It became a hub for a burgeoning jazz and blues scene in Edmonton: Clarence “Big” Miller and Tommy Banks were both repeat customers and huge fans of the restaurant. Debbie Beaver has stated that Banks picked up his love for jazz while hanging around the restaurant. Gospel musician LeVero Carter told the Royal Alberta Museum podcast that Melton’s restaurant was a venue for up and coming local musicians, but the food was the main draw. Carter told the podcast: “We used to say ‘slap your grandma in the face,’ it was so good!” When Pearl Bailey came to play at the Northern Jubilee Auditorium in 1961, she stopped in at Hatti’s Harlem Chicken Inn, as did the Harlem Globetrotters. Black American players from the Edmonton Football Team, also hungry for a taste of home, were repeat customers.

The Harlem Chicken Inn had become a successful business, but Melton saw her mission as one of social uplift. Williams, along with many other Edmontonians, got his first job at Melton’s place. Everyone around town knew they could count on Melton for a meal, and on at least one occasion, a hungry resident took advantage of her generosity. Police reported to the Journal that a man walked in the front door, grabbed a plate of steak and potatoes, and then fled out the back door to consume the meal.

By the end of her life, Melton had created a rare inter-racial institution that incubated a local music scene and lent this Northern city some Southern flavour. And yet, when she died in 1969, there was little public acknowledgement of her impact on the community. Although Melton had advertised in the Edmonton Journal for a quarter-century, the newspaper ran news of her death as a small announcement, rather than an obituary.

There are no public signs, plaques, or street names commemorating Melton or her landmark restaurant, and yet the collective memory of “Hatti’s place” remains anchored in the minds of those lucky enough to have savoured the food or worked in the kitchen of Hattie Melton.

Dr. Russell Cobb © 2021

Read The Last Black West: Oklahoma Freedmen Seek Refuge in Alberta, Part 1.

Read The Last Black West: Oklahoma Freedmen Seek Refuge in Alberta, Part 2

[1] Hot tamales might seem like an outlier to the uninitiated in Southern foodways, but these cornmeal delights have been a feature of the landscape in places like Mississippi and Texas since the 19th century.

[2] “Hatti’s Harlem Chicken Inn,” Intangible Alberta podcast, February 2, 2020.