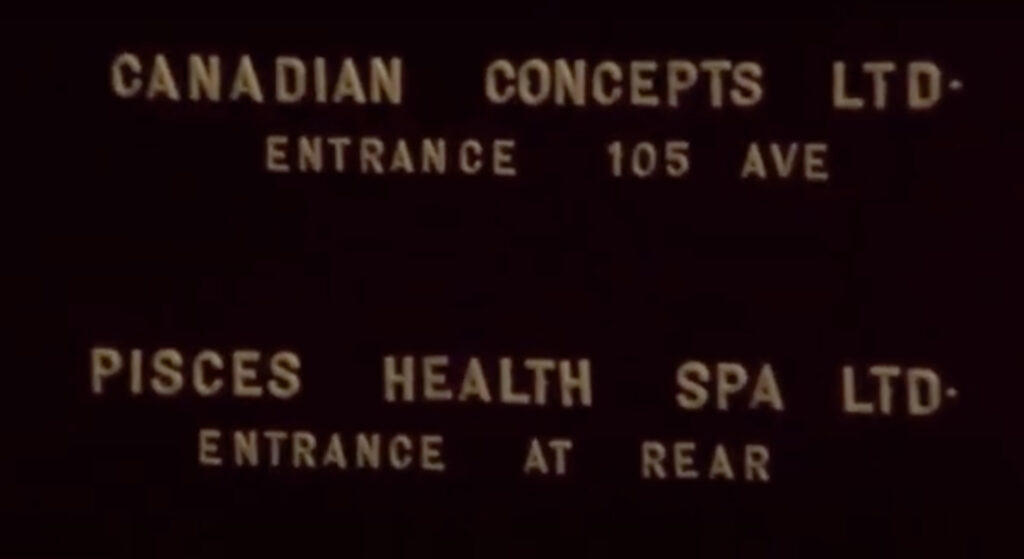

After the Pisces Health Spa opened in Edmonton in 1978, word spread quickly that it was the best-kept gay bathhouse on the prairies — and perhaps beyond.

The Pisces was not the first bathhouse in Edmonton, nor would it be the last. The notorious Georgia Baths had been in business for decades, and although not officially a gay bathhouse, it slowly became one with the advent of modern plumbing, as bathing and hygiene became common. A bathhouse in the prominent Gibson Block was queer enough that it merited a mention in the infamous Naive Homosexual guidebook that made the rounds in Canada’s queer community in 1970. The Gemini bathhouse, which began in a downtown basement, moved to a location on Jasper Avenue that had once been the home of Edmonton’s first gay disco, Flashback.

But all of these bathhouses paled in comparison to the Pisces.

The Beginnings of Edmonton’s Newest Bathhouse

According to men who visited the spa regularly, the place was spotless due to the detailed eye of John Kerr, the manager. He was a former choreographer known to the Edmonton community for his clever work directing the drag queens who comprised the Flashback Follies. John kept Pisces fastidiously clean, which resulted in a successful business; the spa boasted over 2,000 paid members at its peak — a membership list that would become very important in the days after the raid.

The Pisces Health Spa was the brainchild of Pat Fortier, who approached the prominent Edmonton neurologist Dr. Henri Toupin to finance the venture in 1978. Toupin agreed, but his initial investment was swallowed up in rising costs and, after Fortier left the business, Toupin found himself owning a bathhouse instead of being the silent partner he had agreed to be. His plan was to stay in the business until his initial investment had been recouped and then transfer the business to his lover, Eric Stein, and the new manager of the spa, John Kerr, a patient of his who had perhaps become a friend.

A Pattern of Raids

In February 1981, a series of bathhouse raids in Toronto called Operation Soap resulted in the second-largest mass arrest in Canadian history. Bathhouse raids had been happening in Toronto, Montreal, and Ottawa since 1968, but Operation Soap indicated an increased ferocity, as four bathhouses were raided on the same night.

As these raids were occurring, and as the queer community was voicing opposition to the overreach of police powers, fighting back with loud, angry protests in the streets of Toronto, an undercover operation was discretely underway in Edmonton. Beginning in February that year, pairs of young undercover police detectives — nine in total — were posing as members of Pisces Spa, spending weekend nights mingling, watching, and making copious, detailed notes concerning the activities — sexual and otherwise — of the men who gathered there for the purpose of sex.

The Edmonton Police Service has always maintained that the sting operation was inspired by a complaint from a member of the gay community: Fred Griffiths. Griffiths admitted that he had filed a complaint, being disgusted by the goings-on at the bathhouse even though he had never been inside. He finally entered the bathhouse at the urging of the police, who used him as a civilian informant. His reports about what went on inside the spa provided the insider evidence necessary to allow the investigation to begin.

But the fact that the raid was part of a series of raids across Canada that year, coupled with the history of regular bathhouse raids nationally since the decriminalization of homosexuality in 1969, suggests that this pattern of police harassment was already a tried and tested form of intrusion. Indeed, by the time the Pisces was raided in May 1981, dozens of raids had occurred across Canada between 1969 and 1981, resulting in hundreds of arrests. It’s important to view the 1981 raids in that context, as the Pisces raid was far from the first. That year was different, however, because it had the distinction of being the year that the Canadian queer community began to resist.

Infiltration

An owner of an adjacent business with a window overlooking the back-alley entrance to the Pisces was enlisted to allow his location to be used for months as a surveillance centre. From there, spa patrons were surreptitiously photographed and filmed coming and going from the premises, and license numbers of cars parked nearby were recorded.

The detectives’ notes reveal that the focus of the investigation was the common areas such as the dark room, the steam room, and the jacuzzi, where group sex supposedly occurred. After the first detective who had volunteered for the operation completed his first visit, it became apparent that the detectives would be more effective if they were in pairs, so afterwards the detectives would arrive as couples, present their membership cards, and pay the cover charge, which allowed them the cover story of being partners meeting at the spa.

Once inside, the detectives would share a room and change into the obligatory uniform of bathhouse cruising — a white towel around the waist — and move through the spa on the lookout for anything sexual. They made pages of notes on everything they saw, heard, and even smelled. Descriptions were explicit, sometimes with dialogue, from detailed accounts of sex acts with multiple partners to the sounds of a couple of men in the next room, to the men laying on the small beds in the small rooms with the door open, masturbating.

These notes — almost pornographic in nature — describe an active bathhouse, but in a few cases, they reveal how the young detectives viewed the men they were investigating. In addition to the detailed notes of the sex they witnessed, conversations they noted reveal men discussing where they were from, how they became gay, and other small talk. In the notes, there is a layer of judgement, mixed with flashes of empathy towards the members of the spa.

The detectives were greeted as regulars by the men working the front door. At one moment, one of the detectives had forgotten his membership card, which was needed to gain entry to the spa. He was allowed in despite his error, but he and his partner were scolded for not following protocol — just as any ordinary member would be — with the attendant in charge of admittance portentously warning, “We don’t want what happened in Toronto to happen here.”

The attendant’s comment shows that the Edmonton gay community was hyper-aware of the social climate within which they operated and knew that there was more than a chance of a similar event transpiring in Alberta, which was several years behind the rest of the country in terms of acceptance of gay lives.

A Close Call

There were even moments when the entire operation was nearly upended: one evening, the detectives were recognized by a patron of the bathhouse — a prison guard who knew them. Not only did he attempt to make contact with the detectives within the spa, he even followed them out of the bathhouse and into the alley to talk to them. What they discussed is unknown as that part of the detectives’ notes are redacted and no further references to this guard appear, inspiring questions as to what happened to him: was he warned to stay clear of the premises for a while? Or was he reassured by a lie and continued as before?

One night, while buying sex aids at the front counter, one of the detectives makes a reference to the fact that he and his “partner” are celebrating an anniversary. As they left the spa hours later, the attendant working the front door wished them a happy anniversary.

Middle-of-the-Night Machinations

At 1:30 in the morning on May 30, 1981, the detectives made one last undercover visit. At the same time, across the street, in a parking lot adjacent to the railyard, several dozen police officers gathered, awaiting orders from the Chief of the Morality Department.

The undercover detectives waited to give each other a prearranged signal; when that happened, one of them stepped behind the counter. The attendant shouted that the man wasn’t allowed behind the counter. As the detective’s partner held open the front door, 40 Edmonton police officers and a dozen RCMP stormed inside. As the officers burst in, one of them turned the music that always played inside up loud, which deliberately covered the sounds of the police as they made their way through the bathhouse, headed for their assigned rooms, and kicked in any doors that were locked. They stormed in in pairs, and each set was in charge of gathering the men in two specific rooms.

The Ident (identification) Department, with video cameras and still cameras, entered the spa along with the police, with their own assigned areas and tasks, recording the proceedings for evidence. Every man in the spa was told he was under arrest for being a “found-in” in a “common bawdy house.” He was warned that anything he said could be used against him. If the men tried to put on clothes, they were ordered to remain as they were until they had been photographed. Every man was photographed in whatever state he was in as he was rounded up — even if he was naked in the shower or lying on his bed in a jock strap or a towel — and once his identification had been logged, he was ordered to get dressed before being photographed again, this time holding a piece of paper with his name and information written on it.

It was extremely unusual to have a Crown Prosecutor present at any raid, but the Edmonton raid had two Crown Prosecutors present, surveying the arrests. Everything about the raid had been arranged beforehand in great detail, including having staff ready at the courthouse for an extremely unusual middle-of-the-night arraignment.

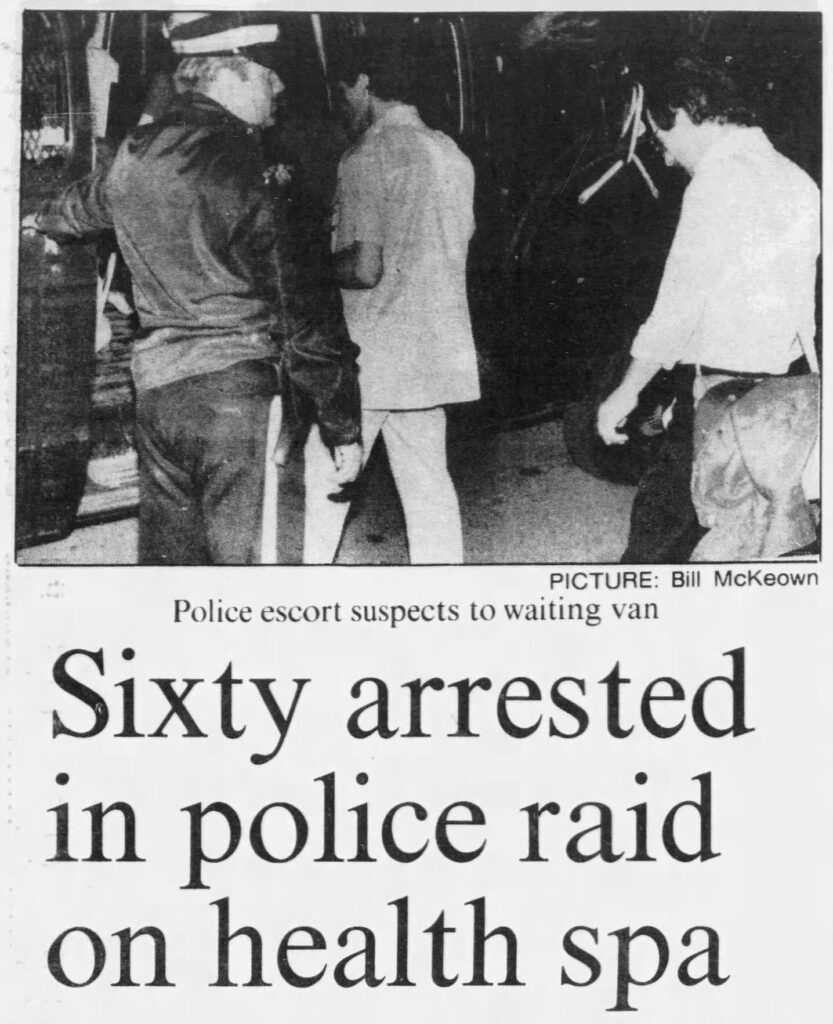

The men were filed out of the spa and into vans and police cruisers and driven to the courthouse, where a few were pulled aside and questioned, and no one was allowed counsel. It was close to daybreak when the 56 found-ins finally made their way out of the courthouse.

At the same time that dozens of police were swarming through the Pisces, arresting everyone inside, another team of police arrived at the Saskatchewan Drive home of Dr. Henri Toupin and Eric Stein. They were both arrested and charged with being “keepers of a common bawdy house.” As the officers executed a search of Toupin’s home, he asked them to not damage anything. Items were seized from their bedrooms — items like poppers and Vaseline — as if proof was needed that they were gay.

Police also arrived at the apartment of manager John Kerr, who was not working at the spa that night, and arrested him as well, driving him to the spa to answer questions. As Kerr arrived with the police, men were still being processed in the TV lounge and escorted to the waiting vans.

Immediate Aftermath

The media recounted the raid the next morning with enthusiasm. The headlines were large and loud, and the televised news joined the chorus. In particular, one egregious overstep was made by CFRN (now CTV) news, who showed the names of the found-ins on the six o’clock news — a move that was met with outrage and charges of double standards and that created a real sense of panic among the found-ins.

The members of the gay community stepped forward in solidarity. Both Flashback and Edmonton’s other principal gay bar, The Roost, offered space for the found-ins to meet and plan their legal strategies. A group of lawyers met the men at the bars to talk them through their options. One of these was Shelley Miller, a young lawyer who ultimately represented the majority of the found-ins. The Gay Alliance Towards Equality (GATE) became a source to provide info on what plans were underway to assist and support the found-ins, to spread the word about the next steps for the men arrested, and to assuage concerns from men all over the province who called GATE to inquire about the plans for the 2,000-name membership list that had been seized in the raid and which featured prominently and ominously in the myriad media reports. Once CFRN showed the names of the arrested found-ins on the news, there was a tangible and not-unfounded fear that the membership list could be released, publicized, and used to pursue further legal harassment of the spa clients who were not present on the evening of the raid.

As the community worked to create a unified response, their solidarity was undone by the sudden news that Toupin, Stein, and Kerr had pleaded guilty to being keepers of a common bawdy house. Toupin’s plea was in response to his obligation to his professional association to shield it from being dragged through the scandal, and Stein and Kerr followed suit — something Kerr regretted later. One by one, many of the found-ins then prepared to plead guilty. Shelley Miller, who defended over 40 of the other men charged as found-ins, recalls that she had one client she was hopeful would be acquitted, and he was the first one to face a judge. But when that client was found guilty as charged by the court, the dominoes began to topple.

Silence: No Longer an Option

As the trials proceeded through the summer months, it became apparent that instead of forcing the gay community to retreat into the shadows, the perceived overreach of the arrests had emboldened the community to resist. Not only was there a protest in front of city hall to draw attention to the injustice, but real outcry came from the frustrated community. The formation of a Privacy Defence Committee was one of the responses to the raid, as Doug Whitfield of GATE sprang into action. Another cheekier, more visible — and purely Edmontonian — form of protest was the creation of a floating protest for the annual Klondike Days Sourdough Raft Race. The S.S. Pisces 2, featured on the front page of the Edmonton Sun, refused to be silent and took its place among the rest of the floats with a pink triangle for a sail.

Despite the efforts of the defence counsels, once Toupin and his team pleaded guilty, there seemed little point in fighting the charges for the found-ins. In the end, the majority of them pleaded guilty and paid their fines. Oddly, the fines varied from person to person. One of the few men to fight the charges and take the appeal to its final conclusion was future queer icon and political pioneer Michael Phair, who ultimately received an unconditional discharge, meaning there was no record of him ever being arrested. But few heard that part of the Pisces story, because by the time his appeal had wound its way through the legal system, it was over a year later, and nobody cared anymore.

Later, stories circulated of men who had been forced to leave their small towns and men who had disappeared rather than appear in court. To this day, the majority of the surviving found-ins have never spoken on the record of their experiences.

After the raid and court cases, what remained was a sense of frustration and outrage that would become a prominent characteristic of the Edmonton gay community. In June 1982, the city’s first Pride events began. There was no parade, but several small events grouped together to honour the theme “Gay Pride Through Unity” attracted 250 people. These events grew into Gay and Lesbian Awareness Week around 1984. It would be a decade after the raid before the first Pride Protest/Parade would take place, infamously featuring people with bags over their heads to protect their identities. Official support finally arrived in 1993 when Mayor Jan Reimer proclaimed Gay and Lesbian Pride Day.

But the complacency was in the past — and the outcry subsequent to the Edmonton raid and others in Canada has been recognized as the ignitor of a new era of activism in Canada’s queer population.

Darrin Hagen © 2021

Read about some of the individuals who were at the Pisces Health Spa that night and how the raid forever changed their lives.

Part 2: After the Pisces Bathhouse Raid: Millie – I’m Number One

Part 3: After the Pisces Bathhouse Raid: Dr. Henri Toupin – Dignity in the Eye of the Storm

Part 4: After the Pisces Bathhouse Raid: Michael Phair – LGBTQ2S+ Activist and Community Leader

Part 5: After the Pisces Bathhouse Raid: John Kerr – Dance for Gramma