As of this writing, Michael is one of the few men charged as a “found-in” to speak publicly on the record about the events of May 30, 1981.

Michael had moved to Edmonton only a year before the raid. He was already active in the queer community and was at the Pisces Spa when the 56 police officers entered the bathhouse in an organized raid that swept 60 members of the gay community into a web of scandal, shame, and persecution. Michael remembers: “The police raided about 1 o’clock in the morning; they came in — a crew of them. They also had a camera filming at the same time. They came down the hallway. They were filming everything… the cameras going everywhere.”

These startling images of the state invading a private space four decades ago still cause alarm. The raid was a coordinated attack on queer safe spaces, the latest in a national series of such raids, and dozens of men — including Michael — had their lives turned upside down, in some cases altering the course of their lives.

“So then they arrested everyone, and took a picture of everyone with a number — or I think it was a number — and then… they let everyone get their stuff and then started filling up paddy wagons and taking them to the old court house.”

The courthouse was ready for them. At a 5 a.m. hearing, the men were held without being allowed legal counsel.

“Then they had somebody else, a court official, who indicated that they were going to question everyone individually — and that’s when a number of people started saying, ‘Wait a minute — What is this? – Everyone individually? What’s going on? We need to talk to a lawyer.’”

“They repeated the same thing again almost word for word. ‘We’ll call your name.’ At that point, there was quite a bit of tension and worry. And they did that — I would say for 8 or 10 people — one at a time. I don’t know if anyone knows exactly how many.”

The men were interrogated at the courthouse about what went on in the bathhouse. Even though they were told at that time that nothing they said could be used against them, there were no guarantees that what they said couldn’t be used against everyone else.

“… and then the same guy came back and said, ‘Everyone can go; you got your tickets for your court date.’”

An advertisement for GATE from the Womonspace newsletter, May 1984, volume 2 number 5, page 6. Accessed via the Rise Up Feminist Archive at https://riseupfeministarchive.ca/wp-content/uploads/WSN-may-1984.pdf.

“I was part of the Defence Committee. And we met with the lawyer a number of times, to work through what the case might look like and what information could be gathered. Actually, there were a whole slew of meetings about all that. And we did some things to raise some money. We never raised very much, and the lawyers involved never got paid very much.”

While the media breathlessly covered the proceedings as they wound their way through the courts, Michael was involved in another purely Edmonton-style protest. Part of the annual Klondike Days celebrations involved a whacky and wet event on the North Saskatchewan River called the Sourdough Raft Race. In July 1981, the race showcased a special float: the S.S. Pisces 2, featuring an outhouse — and Mr. Phair in the flesh, campily dressed as a bright yellow rubber duckie. The floating protest was featured on the front page of the Edmonton Sun.

By the time Michael’s court dates came up, his defence counsel, Shelley Miller, convinced Michael he was ready to present his own case in court. The cases were all very similar as the charges of being found in a common bawdy house were applied to every man found in Pisces that night; Michael had seen many of the trials, so he did his own defence.

“And lost… I was found guilty. And then for the sentencing, you can do things about your character — so I did that and I was sentenced. To tell you the truth, I don’t even remember what, but I appealed it. A couple of us did. Shelley had said she thought I should try and so I did. And then to the appeal court. It was probably over a year later before that actually took place. […] Then you wait for the verdict on that to come down. And they gave me an unconditional discharge.”

The charges were removed from Michael’s record as if they had never existed.

“I think there were a couple of others that that had happened to too; I’m not quite sure. By that point, the whole scene had ended, was over, and no one was paying attention anymore. There was never anything in the media with any of the appeal stuff. I mean, it was a year plus later. That was old history… except for us individuals.”

It’s often been stated that 1981’s bathhouse raid inspired a whole new energy of gay activism in Edmonton. One need look no further than the example of Michael Phair to see that claim realized. Inspired by the events he had witnessed, Michael became a leader in Edmonton’s LGBTQ2S+ activist community. From that day forward, he has been at the centre of nearly all the movements and landmark moments that illustrate the progress of queer Edmontonians as the struggle for equality and empathy moved forward.

Michael began working closely with GATE and being involved in every facet of queer life in Edmonton. It was around his dining room table in Oliver that the idea came to launch Edmonton’s first LGBTQ choir, Edmonton Vocal Minority, which is still creating music 40 years later. He was instrumental in the formation of Gay and Lesbian Awareness (GALA), which, in addition to advocating for equality, produced summer events like picnics and dances — even a croquet match in Rundle Park between the leather queens and the drag queens in the years pre-Pride Parade.

In 1983, at its annual Coronation Ball, the Imperial Sovereign Court of the Wild Rose honoured Michael with the John DeSmit Citizen of the Year award. The group is the Edmonton chapter of the International Imperial Court System, a group of drag organizations that flourished up and down the west coast.

Edmonton’s queer community was about to face its most significant and deadly challenge yet as the spectre of the plague decade loomed over our city. As one of the original founders of the AIDS Network, Michael became a persistent and effective champion of persons living with HIV, working for both the AIDS Network and HIV Edmonton to raise awareness and use his influence to better the lives of those excluded from the care and compassion of society.

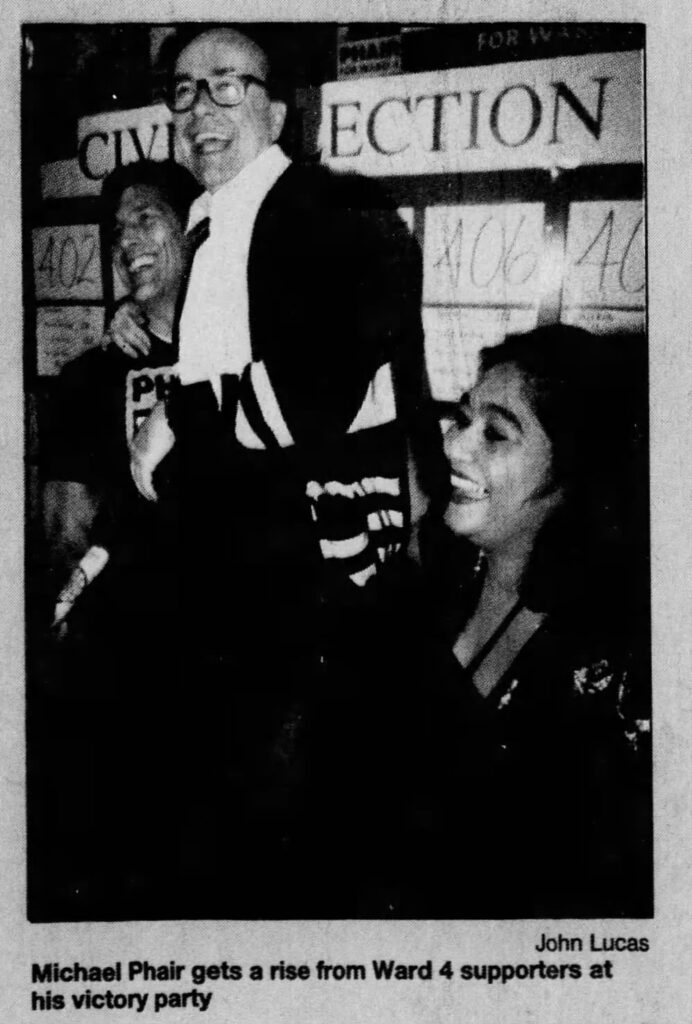

In 1992, Michael ran for — and won — a position on Edmonton’s City Council for Ward 4, becoming the first openly gay politician ever elected in Alberta. It was a watershed moment, not just for Edmonton, but for the province. For five successive terms (1992-2007), he represented the constituents among whom he lived, spearheading forward-thinking policies concerning the environment, diversity, and even Edmonton’s move towards becoming a non-smoking municipality.

Edmonton Journal, 25 October 1992.

In 1998, Alberta’s government had its homophobia challenged in the courts. Delwin Vriend had been a teacher at King’s College, and when he was fired for being gay, the impact of the queer community not being protected by equal rights legislation became clear. Vriend could not challenge the firing because it wasn’t against the law to fire gay people in Alberta. Vriend launched a case against the Alberta government to challenge this, and as the case made its way to the Supreme Court of Canada, Premier Ralph Klein, encouraged by the extreme right elements of the government like MLA Stockwell Day, dug his heels deeper into the entrenched homophobia that for decades defined this province. Klein threatened to invoke the notwithstanding clause to stop queer Albertans from being treated as equals. As one of the city’s most prominent gay figures, Michael became the target of homophobic harassment, receiving threats and horrific hate mail at City Hall intense enough that he was forced to take a short leave of absence from his duties on City Council.

The harassment had brought home — in a real and tangible way — how vulnerable even elected queer people were to the intolerance of Alberta’s anti-gay political stances. Eventually, Klein realized his battle against gay rights was pointless and backed down, allowing gay rights to be “read in” to the law of Alberta. Michael returned to his office in City Hall to serve for 12 more years, finally resigning from civic politics in 2007, whereupon he was often referred to as “the best mayor Edmonton never had.”

Although retired from politics, Michael didn’t retire from his life as an activist and a symbol of courage and dignity in Edmonton. Since 2007, he has been at the centre of many of Edmonton’s movements, been Grand Marshall of Pride Parades, and actively participated in every possible queer cultural event including the Edmonton Queer History Project. In 2015, he became the first LGBTQ2S+ person to have a school named after him, and in 2018, a park on 104 street — once the main artery for the LGBTQ2S+ community and home to the most prominent location of the GATE office — was named in his honour.

Watching Michael’s tenacity and enthusiasm for life over the past four decades, one gets the impression that he’s just getting started.

Darrin Hagen © 2021

Read Part 1: The Pisces Bathhouse Raid: Igniting Four Decades of Activism

Part 2: After the Pisces Bathhouse Raid: Millie – I’m Number One

Part 3: After the Pisces Bathhouse Raid: Dr. Henri Toupin – Dignity in the Eye of the Storm

Part 5: After the Pisces Bathhouse Raid: John Kerr – Dance for Gramma