Henri Toupin was born in Legal, Alberta, on March 15, 1923. He acquired his B.Sc. in 1947 from the University of Alberta and his M.D. in 1949. He became a board-certified neurologist in 1957, actively practicing from that date at the Royal Alexandra Hospital and the General Hospital in Edmonton.

By the late 1960s, Dr. Henri Toupin was a renowned neurologist who was actively involved in Edmonton’s medical community. He was on the Board of Emergency Medicine and held the Chair of Neurology at the General Hospital. From 1965 on, he was an assistant professor of clinical neurology at the University of Alberta. He operated his medical practice from an office in Le Marchand Mansion and lived in a beautiful home on Saskatchewan Drive overlooking Hawrelak Park.

Dr. Toupin was also gay. He engaged with the gay community but, like many queer professionals of the day, did so discreetly because in 1970 Edmonton had its first gay bar, but it was still a city where homosexuality could be used to punish a person professionally.

John Reid, the man who would later open Flashback (Edmonton’s first gay disco), recalls his first meeting with Dr. Toupin at the Athabasca Hotel in Jasper in the early ’70s. Reid was in the earliest stages of coming out of the closet, and the friends who were helping him through that door — one of whom was the piano player at the hotel — introduced him to Dr. Toupin.

Once Reid had made his way to Club 70, Edmonton’s first and only gay bar at the time, he met Toupin again, and the two became friends. Reid recalls that Toupin was “a romantic — he was looking for a lover to spend his life with.”

When Eric Stein first spotted Toupin at Club 70, he grilled John Reid for more info. Reid quipped, “He’s a very nice man… stay away from him.” Stein responded, “I’m gonna’ marry that man.”

Toupin and Stein did become partners, first in life, and then in business. Stein had ideas for businesses to launch in Edmonton, and Toupin had the funds to make those dreams real. By 1978, Eric’s Framing had expanded to two establishments in the city.

In 1978, Toupin was approached by gay entrepreneur Pat Fortier with the idea to open a gay bathhouse in Edmonton. Toupin agreed that the city was in need of such a place for gay men to connect because the only bathhouses in Edmonton were ancient, run-down holdovers from the days of public steam baths. Fortier estimated he only needed $30,000 to build and open a new bathhouse; Toupin agreed to finance it, but he didn’t want to be involved in the business except as a silent partner and only until his initial investment was repaid.

As the spa was being constructed, the future of Toupin’s office at Le Marchand Mansion was suddenly in question; the building was slated for a major renovation, and its fate was unclear. Toupin decided to move his practice into the same building that was about to become the home for Edmonton’s newest gay bathhouse: The Pisces Health Spa.

Pisces Spa opened in 1978 and was soon touted as the most well-appointed bathhouse on the prairies; clean, well-run, and immaculate, it boasted a membership list of over 2,000.

But Fortier’s estimate of the final cost was unrealistic, and costs ballooned to $130,000. Soon after the spa opened, Fortier left the business, and Toupin reluctantly became the sole proprietor of Pisces. His plan was to get his investment back and then hand it over to his partner, Eric Stein, and to the new manager he had hired to oversee day-to-day operations — one of his patients, John Kerr.

At 1:30 a.m. on May 30, 1981, dozens of police raided the Pisces Spa after a months-long undercover investigation. While the police were hauling dozens of gay men out of the spa, police were also arriving at the Oliver-area apartment of manager John Kerr and at the home of co-owners Dr. Toupin and Eric Stein. All three of them were charged with “keeping a common bawdy house.” Their homes were searched for pertinent evidence: documents in Toupin’s home safe were seized by police, as well as sex toys and jars of Vaseline.

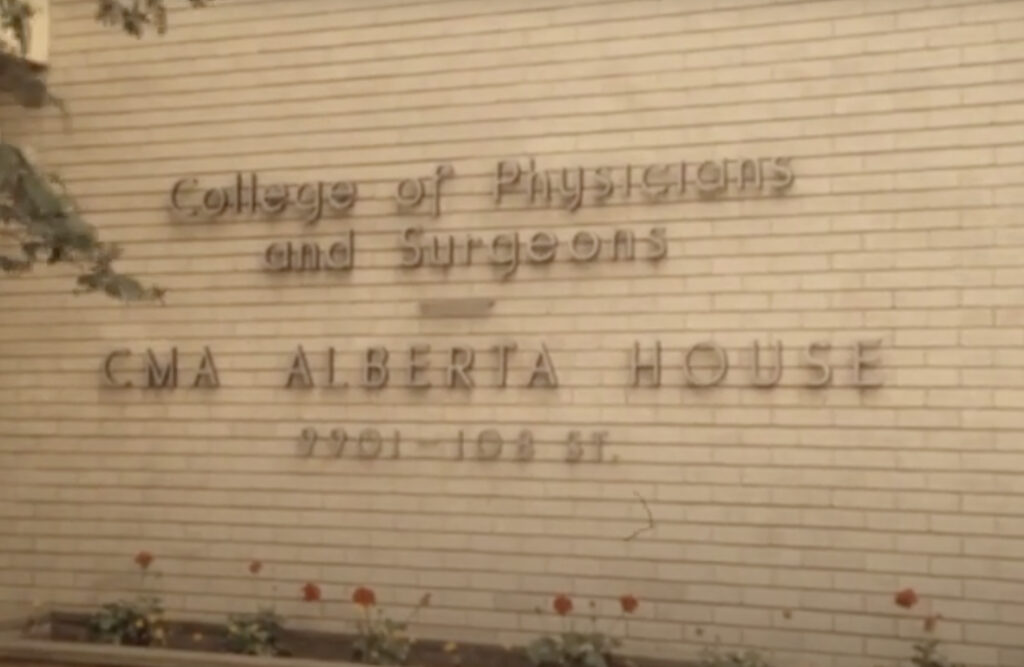

Toupin pleaded guilty to the charges of keeping a common bawdy house, ostensibly to avoid dragging his profession through the mud; he was a member of the Alberta College of Physicians and Surgeons and had a professional obligation to shield the organization from the scandal. Stein and Kerr, being represented by the same lawyer as Toupin, followed the same legal advice. Their guilty pleas shocked and upset the other “found-ins” as it was a very different tactic from what had been successfully applied in the Toronto bathhouse raids in the weeks leading up to the Pisces raid. There, all the bathhouse owners had pleaded not guilty, meaning charges against the found-ins were ultimately dropped. Kerr had always maintained that he didn’t consider himself guilty but had pleaded guilty on legal advice.

Toupin’s guilty plea triggered a disciplinary hearing, and on June 5, 1981, the Alberta College of Physicians and Surgeons met to hear evidence and to decide what action to take in response to his plea. His defence counsel for both the Pisces raid charges and the medical hearing was Robbie Davidson, who also represented Eric Stein and John Kerr in the raid charges.

Davidson recalls the details of the College hearing: “I called character evidence that was unbelievable — I mean basically, the disciplinary panel and the lawyer representing the College were emotionally moved — as was I — by the evidence that was heard: evidence from parents who had had their children treated by Dr. Toupin successfully for serious neurological disease, and they didn’t care what his gender was, and they didn’t care that he’d been convicted of an offence. They thought he walked upon water.”

“An order of nuns that testified… and understand how they must have felt at such a trial, but the nuns said the same thing: he’d given selflessly to them; he donated charitable hours; he performed unbelievable surgeries… they certainly made it quite clear objectively that it didn’t impact upon their opinion of him whatsoever as to his good character.”

As Davidson presented to the assembled appellant jury 40 years ago, “He has been ostracized by members of the homosexual community. They think Henri Toupin’s a coward… Now Henri Toupin finds himself almost friendless, appears a shattered man. He wants to practice medicine, and hopes that after today he will be able to practice medicine.”

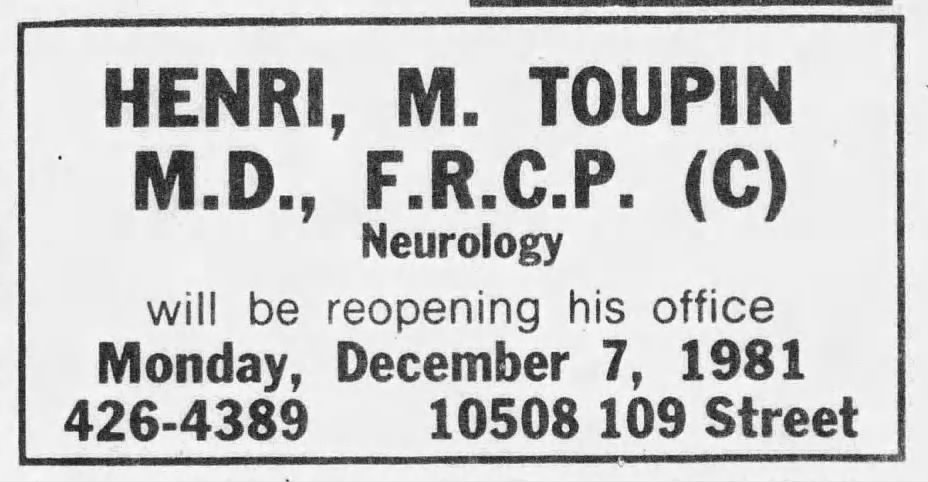

The two-hour hearing resulted in a six-month suspension of Dr. Toupin’s medical license for “bringing discredit to the profession through unbecoming conduct.” The College president also delivered a serious reprimand, and Dr. Toupin was ordered to pay the College’s legal costs.

Toupin’s secretary during those years, Cynthia Krys, recalls that after the hearing, Toupin called her and gave her direction to cancel clinics and advise the patients who had been booked where they could receive services. “He was worried about what his colleagues would think, as well as what his patients would think.” Toupin also expressed concern about Cynthia and his other office employee; Cynthia replied, “Don’t worry about us. We will be back in this office in six months.”

The Pisces trials proceeded through the courts all summer, with headlines blaring, and most of the found-ins eventually pleaded guilty to put the entire affair behind them. Some chose to fight the charges, and when that failed, they launched appeals.

Toupin used this time to attend Harvard and further his studies on the latest in neurology to apply these to his practice once he was back in business. He and Stein also spent time at the log cabin they had built by Lake Eden. Toupin would call Cynthia at the end of her work day and invite her out to the cabin for dinner.

As the six-month suspension ended, Toupin expressed concern about returning to work. Cynthia recalls, “He was worried about coming back to practice; he was worried that he wouldn’t have patients. And I said, ‘Don’t you worry — I’m going to open up the office November 1. Let’s start taking bookings, and we’ll see what happens.’ And I remember the first morning he was back, he phoned me before heading to the office, and he asked ‘Are any patients there? Do you have anybody booked?’ And I said ‘I do.’ So he came in, and we slowly resumed business as usual. But I think he was cautious — not just cautious but worried. His pride was hurt. And whether he was guilty or not, I think having his license suspended — that’s a big blow to a physician.”

For the most part, his patients didn’t seem to care what had happened; they respected his compassion and his skill.

But there was a noticeable change in Toupin. He pulled away from the social aspect of the gay scene — one in which he was only a casual visitor anyway — and for the rest of their lives, Toupin and Stein maintained a very low profile, entertaining close friends at their home or at the log cabin by Lake Eden. According to contemporaries, they were never seen in a gay bar again.

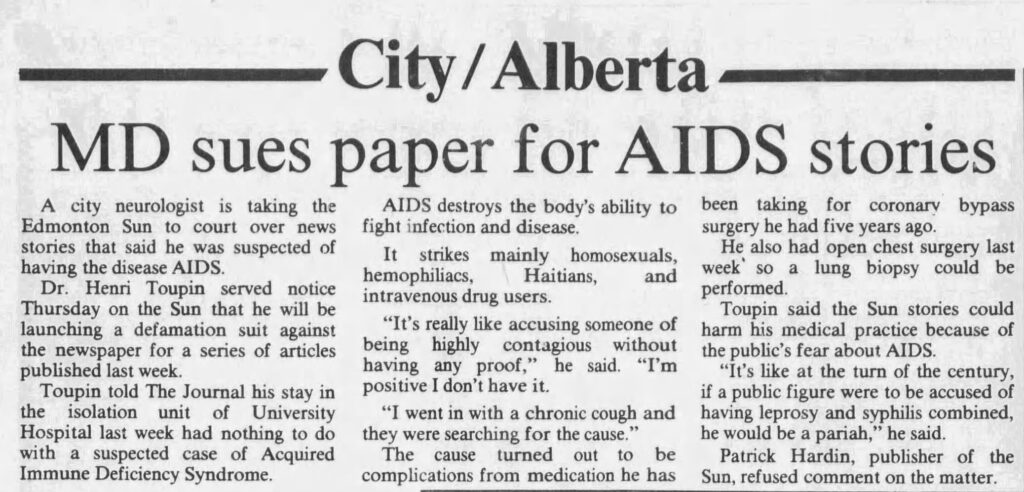

In 1984, Toupin experienced health setbacks and had heart surgery. Shortly after, he developed a cough in reaction to some of the medication and spent time in the U of A Hospital. In May 1985, the Edmonton Sun ran a story announcing that Dr. Toupin was rumoured to be Edmonton’s fourth case of AIDS. This was very near the beginning of Edmonton’s history with that plague of the ’80s, and the morality of “outing” someone with a disease had not yet been debated.

Not only was it a new and dangerous precedent to publicize private medical history, but the Edmonton Sun admitted in the story that Toupin hadn’t even received the results of the test yet. Of course, the story took the opportunity to revisit the Pisces raid one more time, dragging the sordid details back to the surface, as if to remind the reader where they had heard the doctor’s name before. Two more stories followed — one of them exploring whether a doctor with AIDS could transmit the disease to his patients (a grim reminder of how little was understood about this new and rapidly-growing health crisis).

Toupin sued the newspaper for $3 million dollars, citing that his character had been defamed. The Sun responded by demanding to know which parts of the three articles he claimed were false. However, on June 3, 1985, the newspaper printed a retraction that stated in part, “We wish to advise all readers that we now understand that Dr. Henri Toupin has been released from hospital and does not have AIDS. We retract any suggestion or implication that Dr. Toupin has AIDS. We also apologize to Dr. Toupin for any hurt and embarrassment which may have been caused to him by the publication of these articles.”

Toupin’s health declined, but he continued to work, albeit less and less, eventually from his bed while under care at the General Hospital, doing what he could to maintain his practice until his health was too fragile. Ultimately, the doctor passed away from complications due to AIDS on November 10, 1985, at the age of 63 years. Less than a year later, Eric Stein also succumbed to AIDS.

Shortly after Toupin’s death, the Henri Toupin Medical Foundation was formed by former colleagues. In 2006, the executors of Toupin’s estate endowed the foundation with a $3-million gift. The endowment supported two new research chairs: the Henri M. Toupin Chair in Neurology and the Henri M. Toupin Chair in Neurodegenerative Disorders.

In conducting interviews to learn more about Dr. Toupin, a man whose life had enormous impact on Edmonton, this writer was impressed by the recollections of his character. One after another, colleagues and friends remarked on his generosity, his intelligence, and his gentle spirit, even in the face of a storm of antagonism and controversy.

From his secretary and assistant Cynthia Krys, who worked in his office for years until his death in 1985: “I felt honoured to work with him. Not for him — with him.”

From Dr. Barbara Romanowsky, who was a character witness at Toupin’s hearing at the Alberta College of Physicians and Surgeons: “Lovely fellow. A gifted neurologist, quiet, non-assuming — just a nice man — and a very untimely death.”

From John Reid, owner of Flashback: “Very gentle, smart man and didn’t want to impose at all; he was a very sweet soul.”

From Robbie Davidson, defence lawyer for Henri Toupin during the Pisces trial and the College of Physicians hearing: “He was extraordinarily intelligent; he was extraordinarily courteous and polite in demeanour… He, in my mind, would be the definition of a gentleman.”

Darrin Hagen © 2021

Read Part 1: The Pisces Bathhouse Raid: Igniting Four Decades of Activism

Part 2: After the Pisces Bathhouse Raid: Millie – I’m Number One

Part 4: After the Pisces Bathhouse Raid: Michael Phair – LGBTQ2S+ Activist and Community Leader

Part 5: After the Pisces Bathhouse Raid: John Kerr – Dance for Gramma