“The government can make all the laws they want, but they can’t stop people from going on strike… You could get the army out and march them to work, but can you make them work? No. You can threaten people. Maybe you can threaten to kill somebody if they didn’t work. But if they accepted the threat and said, fine shoot me, you still can’t make them work.” – Margaret Ethier, President, United Nurses of Alberta, 1980 – 1988.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Alberta’s nurses voted in favour of strike action on several occasions to push for improvements in pay and working conditions. The province saw the first strike by hospital nurses in 1977, with nurses from seven hospitals including Edmonton’s Royal Alexandra Hospital and the Edmonton General Hospital taking to the picket lines. In April 1980, nurses at 79 Alberta hospitals went on strike. The 1982 strike involved nursing staff at 69 Alberta hospitals. The strikes were successful in generating some improvements for nurses. However, by the end of the 1982 strike, Alberta’s Progressive Conservative government was gearing up to push back.

In 1983, Premier Peter Lougheed’s government passed Bill 44 making it illegal for hospital employees, including nurses, to strike. When Lougheed’s successor Don Getty’s government met the United Nurses of Alberta (UNA) for contract negotiations in 1987, strike action was prohibited. Perceiving the nurses’ union to be in a weaker bargaining position, the government decided to pursue significant rollbacks of gains made by the UNA during the legal strikes of previous years. This resulted in messy, months-long negotiations with the UNA, which had a policy of not giving in to rollbacks.

During a UNA meeting in January 1988, many nurses expressed their dissatisfaction with the government offer on the negotiating table, but unlike previous years, if they were to go on strike, they would be breaking the law. The UNA decided they would hold a vote in which they would pose the following question to their members:

“Are you willing to go on strike for an improved offer?”

The Labour Relations Board was quick to respond, declaring that holding a vote on strike action would in itself be considered illegal. This had the unintended effect of galvanizing support for a strike among UNA members; suddenly the predominantly female group of professionals were being told that they weren’t even allowed to have a vote.

Heather Smith (UNA President from the 1988 strike to the present day) said, “I thanked the chairman of the Labour Relations Board several years later for his ruling because if he had not ruled that it was illegal to even hold the vote, we would never have got the overwhelming turnout we had for the vote.”

The vote was held on the morning of January 22nd 1988. Bev Dick, who later served as UNA 1st Vice President, recalled that voting at Edmonton’s Misericordia Hospital took place in a motorhome because they were unable to hold the vote inside the hospital as they had for past legal votes.

“It was parked across the street from the Misericordia and it was very cold, blizzarding, drifting snow, it was [an] ugly, ugly day. And nurses are walking across that huge front lawn at the Misericordia to cross the street to come and vote. And they were coming in hoards.”

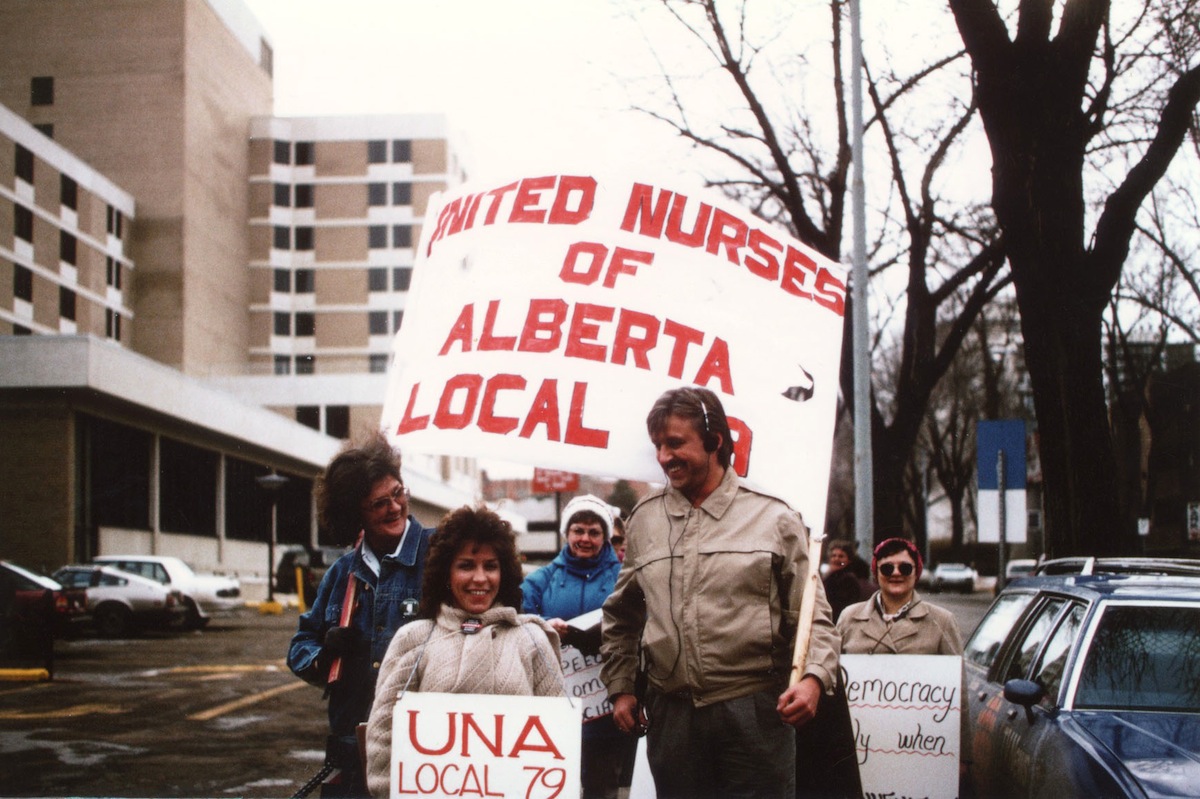

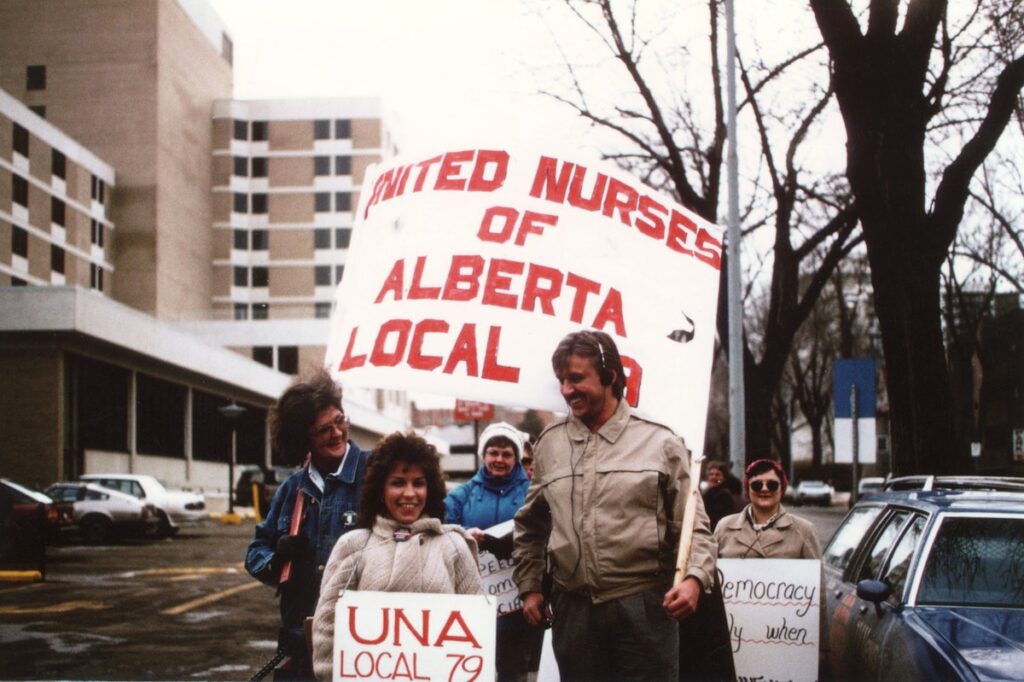

Seventy-six percent of the membership voted in favour of going on strike, affecting 11,400 nurses in 98 hospitals across the province. The strike began on January 25th and lasted 19 days. Those were long days for the nurses on the picket lines, who by the end of the month were facing not only the lows temperatures of -30°C, but also the threat of fines and jail time. One striking nurse, Cynthia Perkins recalled, “I said to my husband, ‘don’t you dare come out and bail me out if they put me in jail. You leave me in there!’”

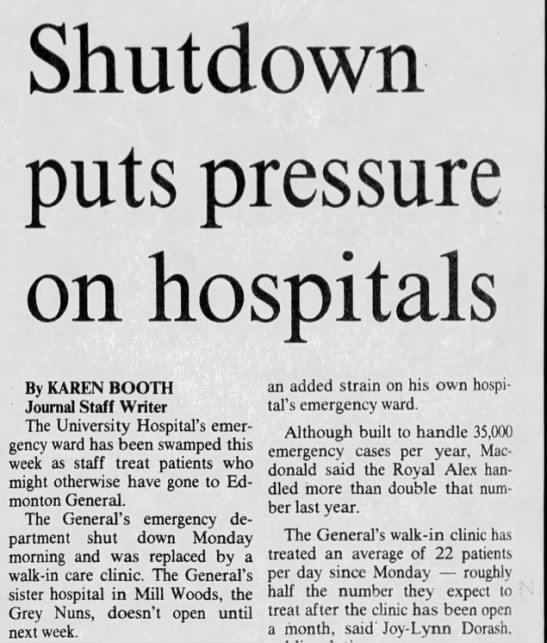

Elective surgeries were cancelled, patients were moved to other healthcare facilities, doctors and other hospital staff worked long shifts trying to keep departments running and many patients were sent home early. The only fully-functional hospital in Edmonton was the University of Alberta Hospital where the nurses were part of a different union.

Public opinion around the strike was divided. Media reports underscored the tensions. Rod Larsen (then Alberta Hospital Association Vice President of Employee Relations) claimed the nurses were, “holding hospital patients to ransom.” Alec Jenkins, a University of Alberta economics professor, argued that the government needed to end the strike by bankrupting the UNA through hefty fines. “A nursing union which retains a large wad of money is like someone with a couple of sawed-off shotguns in his house… It seems to me the intention is to break the law.” College of Physicians and Surgeons Registrar Roy le Riche described the 1988 nurses’ strike as “no different than terrorism” adding, “I did not believe that nurses in their business careers could sink to such depths of degradation. If you are going to place self always before service, you shouldn’t be there.”

Not all of le Riche’s colleagues agreed with his assessment of the situation. Calgary doctor Noel B. Hershfield was among the medical professionals who declared their support for the nurses, writing: “There is no reason why nurses should not go on strike if all of their methods of obtaining what they consider to be their proper financial rewards fail. After all, doctors in this country have done so… There is ‘no aura of mystery’ about the suggestion that nurses are being discriminated against because they are women.”

Margaret Ethier, UNA President during the 1988 strike, noted that a raft of penalties were levied at the nurses due to the illegality of their actions. “First of all, before we even hit the bricks, there were a number of different fines and contempts for having held the strike vote when we were told not to.”

On January 27th, 1988 the UNA was charged with criminal contempt. On the same day, individual nurses began receiving charges of civil contempt, which came with the threat of $1,000 fines and jail time. Over 75 such charges were laid against individuals by the end of the strike. Hospitals across the province also began firing nurses who refused to cross the picket line and return to work.

The government was under mounting pressure to end the strike, and not only because of Albertans’ concerns about the impact on patient care. Calgary was about to become the first Canadian city to host the Winter Olympic Games, due to begin on February 13th. Thousands of athletes, coaches, media representatives and fans were descending on Alberta at a time when hospitals were already overwhelmed. Premier Don Getty cut short his California vacation at the end of January to deal with the escalating situation back home.

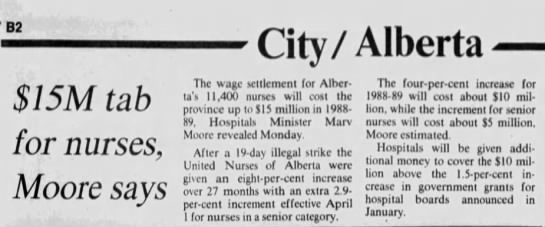

On Friday February 12th, 82% of nurses voted to accept an improved offer and return to work. While some were disappointed that substantial gains had not been made, others felt they had achieved their objective: no rollbacks. It set a tone that benefited the nurses during contract negotiations into the 1990s. Whether the government thought their strikes were legal or not, the message from the nurses was clear: they were prepared to fight for fair pay and working conditions.

Margaret Ethier said of the final outcome: “We won the strike. We didn’t make significant gains… But, it was a lot about respect. We did maintain that they had to respect us, to deal fairly with us. We’re not afraid, we will work together, and we’re tough.”

The UNA was ultimately slapped with $426,750 in fines as a result of the 1988 strike. Donations came in from other unions to help pay the huge sum. Margaret Ethier said, “I took home with me stacks of letters from people who would write in and say, ‘Dear Margaret, I’m just writing to you again because I think it’s so unfair what they’re doing to you. We’re only senior citizens, so we can’t afford too much, but I just want to send you another $50’. It’d just make you cry to read the letters.”

An Angus Reid poll conducted after the strike revealed that when it came the question of whether the government should be allowed to ban strikes for essential workers, public opinion hadn’t changed. 52% of Albertans agreed with the strike ban for nurses.

When Calgary’s Winter Olympic Games began on Saturday February 13th, all but one of Edmonton’s hospital emergency departments were open again. Staff at the University of Alberta Hospital were exhausted after almost three weeks of being Edmonton’s only fully-operational hospital. The emergency department was temporarily closed so that burnt-out employees could take a break.

Josephine Boxwell © 2021

Sources

Boehm, Bob, Nurses Eager to Get Back to Work. The Edmonton Journal, February 13th, 1988.

Hershfield, Noel B., Viewpoint: The Alberta Nurses’ Strike. The Canadian Journal of Gastroenterology Vol 2. No. 2 June 1988 pp. 89-90.

Howse, John, Alberta’s Defiant Nurses. MacLean’s Magazine, February 8 1988.

Interview by Alberta Labour History Institute with Margaret Ethier, 2003.

Journal Staff Writers, Hospitals ‘Cope’ Without Nurses. The Edmonton Journal, January 26th, 1988.

Kent, Gordon and Morningstar, Lasha, Gov’t Seen as The Key to Settling Nurses’ Strike. The Edmonton Journal, February 9th, 1988,

Moysa, Marilyn and Gold, Marta, New Talks as Nurses Set to Strike. The Edmonton Journal, January 24th, 1988.

Retson, Don and McLeod, Kim, Hospitals Continue Firing Striking Nurses. The Edmonton Journal, February 11th, 1988.

United Nurses of Alberta, Remembering Alberta’s 1988 Nurses Strike. February 12th, 2013.

United Nurses of Alberta, UNA History. 1977-2017. 2017.

United Nurses of Alberta Local 1 Peter Lougheed Hospital Calgary, UNA 25 Years of History (1988).

Zdeb Montgomery, Chris, Emergency Departments Open Again. The Edmonton Journal, February 14th, 1988.