I remember the first time I met Elba, mother of my close friend Yazmin (or Yaz as friends and family refer to her.) It was at Yazmin’s birthday party. Yazmin and I first met through community arts projects. We worked together to organize community events and eventually grew to become friends. Not only did we share a mutual love of community organizing, but we both grew up in immigrant families and were raised in Mill Woods. While her family was from Guatemala and mine from India, we share similar values. For one, both our cultures are known for their gracious hospitality. On Yazmin’s birthday, Elba had made plates of traditional Guatemalan food – pupusas and tamales. I was intrigued by the origins of these dishes, so I returned a few months later to chat with Elba about this and her journey to Canada.

I visited the Juarez-Maldonado family on a cold evening in February. Shivering, I ran the bell and was greeted with a hug from Yazmin. I could see her Mom, sister, and niece (a toddler at the time) over the stairwell, lounging around the living room. I jokingly told Yazmin that I was here to interview Elba and that we would have to chat later. Soon enough my plans were unraveled, and the interview turned into a casual conversation with Elba and her daughters, Yazmin and Ingrid (or Ali as friends and family call her).

As soon as I sat down, Elba greeted me with her big smile and plate full of food – none other than a plate of hot tamales. Elba’s gracious hospitality and smiling face reminded me of my Punjabi family – no one goes away hungry. Elba told me she felt shy about speaking English, “it is not very good” she said, her face blushing. I reassured her not to worry about it. Throughout the conversation, I apologized for my poor pronunciation of pupusas and tamales, and for taking up too much of Elba’s time. Elba is quick to forgive me; she goes to the heart of the matter – “Amrita, see the thing with food—tamales and pupusas—you can have them anytime, anywhere, with anyone.” Pretty simple. And that is where the story all starts.

Elba Maldonado fondly recalls moving on Febrero séptimo (7th of February) from her ancestral village in the province of San Marcos, Guatemala, to her mother-in-law’s home in the bustling city of Quetzaltenango where she then lived for seven years. “I could not believe that they were using forks and knives to eat their food,” she remembers. “Food is meant to be touched and felt with your hands.” Elba may as well have predicted her future in Canada. Through her family business she served up many “handheld” Guatemalan dishes like pupusas and tamales.

The Juarez-Maldonado family ran Los Comales Guatemalan, a restaurant on 97 Street and 108 Avenue in Edmonton, for 10 years before closing its doors in 2011. The family arrived in Edmonton as part of the second cohort of Guatemalan immigrants. Maldonado, her husband Jorge Juarez, and their five children lived in a shelter in Mexico for six months before arriving in Edmonton in 1994.

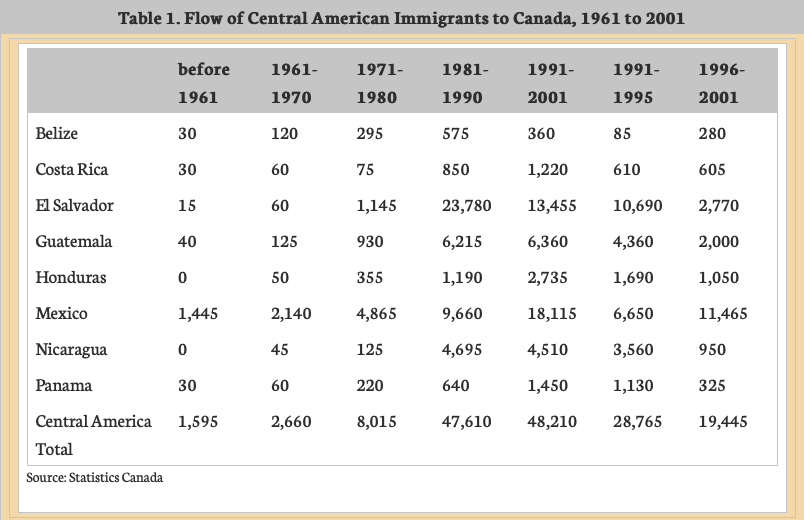

Guatemalans came to Canada in roughly two groupings: the first major wave migrated between 1981-1985 with more than 2,000 people arriving in Canada. This was double the total of the 880 people who had arrived between 1975 and 1980 in an earlier, smaller group which may have been a result of Canada’s 1976 Immigration Act, which added refugees as a distinct migrant category, amongst other reasons.[1] The second cohort came around 1991, when more than 2,000 Guatemalans arrived.[2]

Like many Guatemalans, the Juarez-Maldonado family lived under a succession of brutal military dictatorships and civil war before their arrival in Canada. Failed land reform policies led to an overthrow of Julio César Méndez Montenegro’s pro-democratic Guatemalan government in July 1970, after which, the country returned to a military dictatorship. Guatemala’s 36-year civil war began in 1960 as left-wing guerilla groups started battling government military forces. The country was under autocratic rule by General Miguel Ydigoras Fuentes, who assumed power in 1958 following the murder of Colonel Castillo Armas. The 36-year guerrilla movement ended in 1996 when the government signed a peace agreement with a guerrilla coalition, the Guatemala National Revolutionary Unity (URNG). During the 36 years of civil war, assassinations, kidnappings, violence, and oppression were part of the reality of everyday Guatemalans like the Juarez-Maldonados family.

Today, the family remembers the struggles of their less fortunate countryfolk. Combining their family’s culinary and artistic talents, they work towards bettering life for Guatemalans while feeding the hungry bellies of Edmontonians. Elba and her five grown children—daughters Leslie, Ali, Yazmin, and sons Carlos and Jorge—regularly prepare mass quantities of tamales and pupusas for church events and fundraisers for Communities at Play, a non-profit started by Yazmin that promotes equality, diversity, solidarity, and empowerment for young people in Guatemala.

As I chow down on my rice filled tamales in the Juarez-Maldonado’s inviting and beautiful home, with Yazmin’s traditional Guatemalan artwork lining the walls, I listen to the women speak about Ingrid’s experiences working at Los Comales Guatemala. She picks up her one-year-old daughter, Analia, as she recalls the challenges of being a child of first-generation immigrant parents.

“While other kids were heading to the mall after school, I would take the bus from O’Leary High School to my parents’ restaurant on 97th,” she says. “I remember doing my homework between customers, cleaning, and prepping. Most nights I got home well past midnight.” Ingrid pushes up her glasses. Ali has an air of seriousness. Although she is the youngest of the Juarez-Maldonado daughters, she could be mistaken for the eldest. She quietly listens intently to her elder sister, Yazmin.

Yazmin’s brown eyes light up as she chimes in. “I didn’t help that much, but Ali knows how to cook the best.” Ali smiles with a full grin. It is in moments like these you know you are sitting among family. Elba has her own take on tamales and she’s firm about it. “Well, you need to be careful with your money,” she reminds me, pressing her hands on her traditional floral print apron- something that looks like it was bought in a market in Guatemala. She explains that I should wrap my tamales to-be in aluminum because banana leaf is too expensive. It was only a few years ago that banana leaves became available for purchase at some of Edmonton’s Latin markets, such as those on 118 Avenue. She admits, however, that wrapping in aluminum may compromise the flavor.

Tamales are a traditional Mesoamerican dish made of masa or dough (starchy, and usually corn-based) filled with meats, cheeses, fruits, vegetables, chilies or any preparation according to one’s tastes, steamed in a corn husk or banana leaf. Elba prefers to fill the tamales with maiz (corn) and pieces of meat—leftover turkey from Canadian Thanksgiving, chicken, or, less often, pork. She often tops her tamales with sauce.

Maiz, I discovered, is an auspicious crop. Yazmin and Elba explain that “in Guatemala, maiz is placed at the middle of the home and a prayer is made for bringing such a great harvest. The best corn seeds are redistributed.”

Some diversity exists between varieties of tamales. In Guatemala, they are prepared with corn flour rather than corn. Elba admits that the tamales she makes now are not as fresh and tasty as what is made in her ancestral village. “We ground the corn from the fields from scratch,” she says. “It smells amazing.” A wide smile comes across her face, as she recalls it, “Oh, nothing like it!”

Dinner at the Maldonado-Juarez home would not be complete without discussing pregnancy cravings. Yazmin is expecting her first child in November. “I am craving pupusas,” she says. Elba and Ali understand. I am a bit a confused. Ali goes on to chat about periods of her life where she craves home cooking. I completely understand – I crave a bowl of my Mom’s dahl (lentils) and rice from time to time. There is something about traditional foods that is comforting! Elba goes on to tell me about the differences between pupusas and tamales.

Pupusas are a traditional Salvadorian dish made of thick, handmade corn tortillas prepared with a variety of fillings including cheese, ground seasoned pork, and beans. She prefers to fill them with mozzarella cheese (Elba says I can go to Superstore for this!), black beans, turkey, chicken, or pork. Elba coyly admits that she did not know how to make a pupusa until she arrived in Canada. “I learned how to make this from the Salvadorians at my church,” she says.

Like the Guatemalans, the Salvadorian community in Edmonton also escaped political instability and violence. By the mid-1980s, the Salvadorian community outnumbered the Chileans as the largest legal and undocumented immigrant group from Central America in Canada. The Salvadorians made up approximately 70% of immigrants from Central America between 1982 and 1987. By 1987, 22,283 Salvadorans were living legally in Canada most of whom were young males working in the ‘underground economy.’[3]

Almost 50,000 Salvadorians had already settled in Canada when the Juarez-Maldonado family arrived, compared with approximately 18,000 Guatemalans. The Salvadorians welcomed Elba and her family by helping with their many settlement needs. According to Elba, this included teaching them how to make a very tasty pupusa. In addition to the pupusas, Elba also learnt much about the ‘hidden customs’ of living in Canada. She says, “you learn about what is expected here in Canada, how people talk and act with each other here, how to open a business, what people like to eat here –a lot of things that my family did not know. The Salvadorian community helped us and we, our family, we wish to help others that experienced what we did.” Both of Elba’s daughters nod in agreement.

As I start to getting ready to leave, Elba tells me that I cannot leave without some tamales to take home to my Mom. I tell her that I will be back, soon, with some Indian food, but that I first needed to learn to make it just as my Mom does.

Amrita Gill © 2021

[1] Garcia, Maria Cristina. (2006, April 1). Canada: A Northern Refugee Central Americans. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/canada-northern-refuge-central-americans

[2] Garcia, Maria Cristina. (2006, April 1). Canada: A Northern Refugee Central Americans. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/canada-northern-refuge-central-americans

[3] Garcia, Maria Cristina. (2006, April 1). Canada: A Northern Refugee Central Americans. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/canada-northern-refuge-central-americans.