Read “It’s in our veins,” Part 1

Immigration to a new community involves a dramatic change that can affect nearly every relationship, structure, or value in an individual’s life. Disconnection from one’s home country or community can cause feelings of loss and isolation. These feelings, although individually felt, may be connected to a “socially oriented necessity, connected to an urge to construct the immigrant community.”[1]

Immigrants seek to fill the need for connection to one’s home life and familiar traditions by engaging in sociocultural activities or artforms. Participating in dance forms from one’s home country “offers compensation for the life one has had to leave behind; it is a symbolic activity with the capability of representing everything one misses from the home country. It evokes particular personal memories as well as collective national sentiments.”[2] Studies conducted on students who had the opportunity to participate in folk dances from their Latin American home countries showed that participation in these cultural activities helped them to develop their own ethnic identity and awareness of their role in their non-Latino communities.[3]

During the 1970s, after the Chilean coup, more than one million Chileans left their country under the Pinochet regime, which continued into the 1990s.[4] There are currently so many Chileans living abroad, that even though Chile only has 13 official regions, there exists a virtual 14th region, called el exterior or el reencuentro, comprising of all Chileans living in different communities around the world.[5] In Canada, specifically, the Canadian government opened its borders to approximately 6,000 Chileans seeking asylum following the coup.[6] This influx of Chileans brought with them their own cultural experiences and values that shaped Canada for decades to come. Cafes opened to showcase Chilean music, soccer leagues were created, Latin dance groups were formed, and Chilean murals were painted on several buildings across the country.[7] All of these initiatives, and more, contributed to Canada’s current multiculturalism, but also served as a way for incoming Chilean and other Latin American immigrants to feel more at home. For Chileans living abroad, music and dance have been a popular and effective way to reconnect to the country they left behind. As was explained by Alex Rojas, through his exploration of salsa dancing and salsa music, he was able to reconnect to his Chileno identity and his Spanish mother-tongue. This is undoubtedly the case for many Chileans and other Latin Americans living away from their home countries.

In the lives of first, second, and even third-generation Latin immigrants, identity-affirming traditions are vital, as a symptom of living in foreign countries is substantial acculturative stress. This acculturative stress derives from exposure to or experiencing other cultural values, practices, and languages that differ from one’s ‘home culture’.[8] Sociocultural traditions, such as dance and music, are crucial because they serve as a reaffirmation of one’s home culture. Furthermore, they allow underrepresented groups to enact their identity in places where their cultures are typically silenced by a dominant group, or where they experience discrimination.[9]

Cultural activities and traditions can serve as a way of connecting to one’s heritage while abroad in a new community. For many Latin Americans, music and dance are two of the key mediums through which they can feel a stronger connection to their home countries. Not only can dance help new immigrants find a sense of familiarity and belonging, but it can also help second or third-generation immigrants get back in touch with a heritage that they may find otherwise difficult to access. Dance is not only a form of physical activity; it encompasses cultural histories, traditions and values. Therefore, in learning how to dance, one learns more about the cultural aspects of that particular group than is often realized. Alex Rojas feels great pride in being able to reconnect Latinos living in Edmonton to their roots through his dance studio, ETOWN SALSA.

Furthermore, non-Latinos who participate in cultural traditions such as salsa dancing can begin to identify more with Latin American communities. To emerge oneself in these types of activities is to radically transform one’s identity, leading to a better understanding of cultural values outside of one’s own. ETOWN SALSA encourages Canadians with no experience in Latin dancing to learn more about Latinx heritage and enjoy themselves while doing so. This sharing of cultural traditions leads to a more socially aware space in Edmonton, where the dominant culture is actively taking the time to understand more about groups that would otherwise not be in the spotlight.

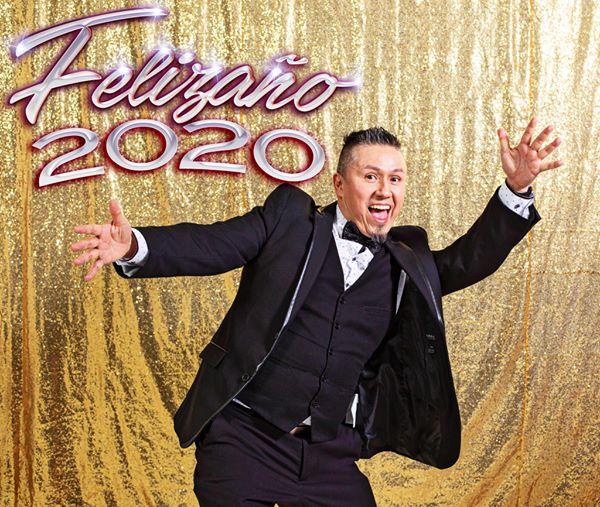

ETOWN SALSA currently offers classes to fit the needs of a variety of dancers. The dance styles taught include salsa, bachata, merengue, Latin line dancing, mambo, cumbia, and cha-cha-cha. ETOWN SALSA provides private lessons, as well as group lessons for single dancers and couples, and they even teach dancing outside of their studios at local schools and corporate events. Apart from hosting dance lessons, ETOWN SALSA performs at Edmonton venues such as the Orange Hub, Sherbrooke Hall, Mezza Luna Nightclub, Azucar Latin Nightclub, and countless more. Additionally, ETOWN SALSA collaborates frequently with a local band, Rumba Caliente, to host Latin dance and music events in Edmonton at venues like the Rec Room in South Edmonton Common. Every year since 2015, ETOWN SALSA has hosted a Latin-themed New Year’s Eve Party at the Renaissance Hotel attached to the Edmonton International Airport. This event includes dance lessons, a live band, Latin-inspired cuisine, multiple DJs, and ample room for dancing. Since this event started, it has grown in popularity every year, as more Canadians and Latinos alike are drawn to the festive celebration.

After conducting research on this matter and seeing the influence that ETOWN SALSA has on dancers of all ethnicities, we feel that it is essential to support cultural activities provided by minority groups. This support can help immigrants feel more welcomed and at home in a new community, while also encouraging locals to learn more about their new neighbours.

Miguel A. Priolo Marín & Nieva W. Srayko © 2020

Click to read “It’s in our veins,” Part 1: Edmonton Dance Schools and Latin American Identity.

[1] Knudsen 2011, 71.

[2] Knudsen 2011, 75.

[3] Meeker 2016.

[4] Knudsen 2011.

[5] Knudsen 2011.

[6] Simalchik 2004.

[7] Simalchik 2004.

[8] Meeker 2016, 123.

[9] Meeker 2016, 124.

Sources Cited

Bosse, Joanna. 2008. “Salsa Dance and the Transformation of Style: An Ethnographic Study of Movement and Meaning in a Cross-Cultural Context.” Dance Research Journal, 40 (1): 45-64.

Flippin, Laura. 2013. “Salsa Remixed: Learning Language, Culture, and Identity in the Classroom.” Working Papers in Educational Linguistics, 28 (2): 74-91.

Hosokawa, Shuhei. 1999. “‘SALSA NO TIENE FRONTERA’: ORQUESTA DE LA LUZ AND THE GLOBALIZATION OF POPULAR MUSIC.” Cultural Studies, 13 (3): 509-534. DOI: 10.1080/095023899335202.

Indiana University Bloomington. 2015. “Sharing Latino culture through dance.” Video, 1:53. https://youtu.be/IlIhbX21jts.

Knudsen, Jan. 2001. “Dancing cueca “with your coat on”: The role of traditional Chilean dance in an immigrant community.” British Journal of Ethnomusicology, 10 (2): 61-83. DOI: 10.1080/09681220108567320.

Meeker, Angela. 2016. “Just Showing Our culture”: Latino/a Students Constructing Counter- Stories Through Baile Folklórico.” Dissertation, San Francisco State University.

Raska, Jan. (n.d.). “Canada’s Response to the 1973 Chilean Crisis.” Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21. https://pier21.ca/research/immigration-history/canada-s- response-to-the-1973-chilean-crisis.

Salinas, Eva. 2018. “How the Chilean coup forever changed Canada’s refugee policies.” The Globe and Mail. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/politics/escape-from- chile/article14176379/.

Simalchik, Joan. 2004. “Chilean refugees in Canada: home reinvented.” Canadian Issues, (3): 52-53. https://login.ezproxy.library.ualberta.ca/login?url=https://search-proquest- com.login.ezproxy.library.ualberta.ca/docview/208699251?accountid=14474.