Throughout Indigenous territories, histories, cultures and stories, there exist a number of locations that hold a special significance, apart from the usual sacredness applied to all things. The knowledge regarding these locations is often protected due to the ongoing effects of foreign intrusion and colonization policies. In contrast, there are locations and Indigenous stories that have become more predominant, however continue to be obscured in mainstream society. Amiskwaciwâskahikan is no exception to this process of obscurity and hidden histories. One such narrative being lost throughout the years is the story and understanding around the entering into Treaty No. 6 that occurred at Fort Edmonton on August 21, 1877.

The notion of Treaty was not a new concept when newcomers began to set foot upon Turtle Island, nor was it an uncommon practice. Often sought as a peace making endeavor to ensure coexistence in a space, two nations collaborate to each make concessions to ensure peace. In terms of North America, this process began and was solidified within the teachings and lifestyles of the Indigenous peoples of these territories. Acknowledging that the notion of ownership was only allotted to the Creator and other deities, Indigenous peoples operated under the law that everything upon this land was provided for our utilization; hence reciprocity and thankfulness must be maintained to ensure the utilization is maintained. Under this premise, land usage and resource extraction were often carried out under the mechanism of Treaty with other tribal nations to ensure co-habitation and co-existence.

Upon arrival of Europeans, Indigenous mechanisms and laws were utilized in interactions with early explorers and traders. Reciprocity, relationship establishment and inter-marriage became tenets in these initial engagements. Nation-to-Nation understandings became more prominent as European countries established settlements, and with the Royal Proclamation of 1763, a formal process for Treaty making would begin with the Treaty of Niagara in 1764. Through these processes, Indigenous mechanisms like wampum belt covenants and others would be married with foreign laws. Issues and practices utilized in this marriage would begin to cloud the process, and allow for concessions to be made that did not fit within the Indigenous paradigm or worldview.

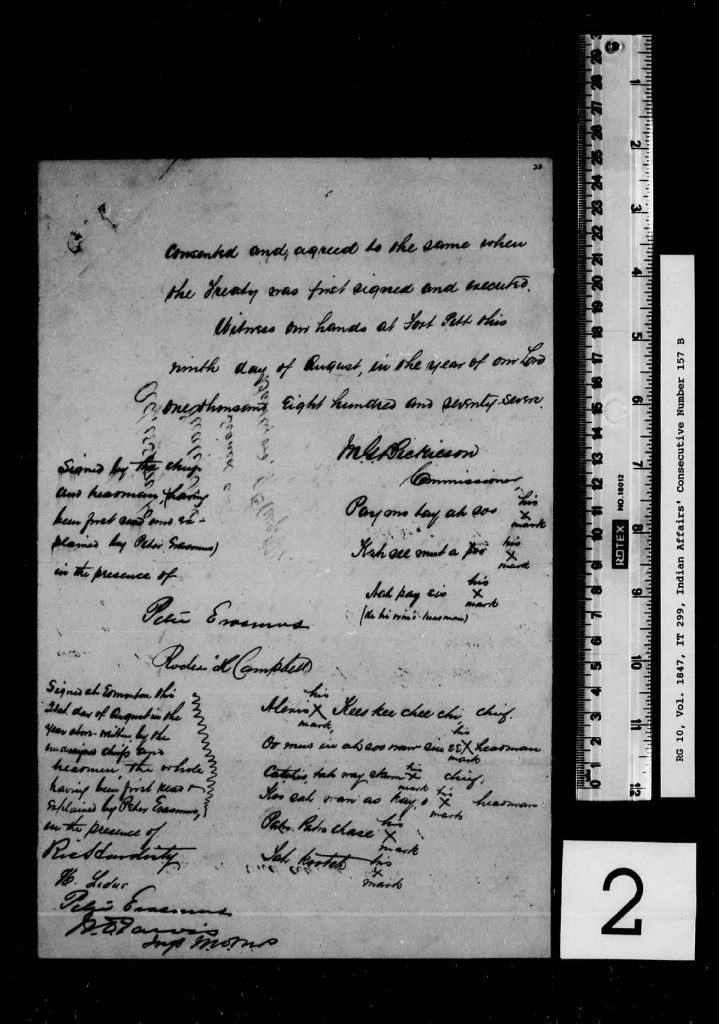

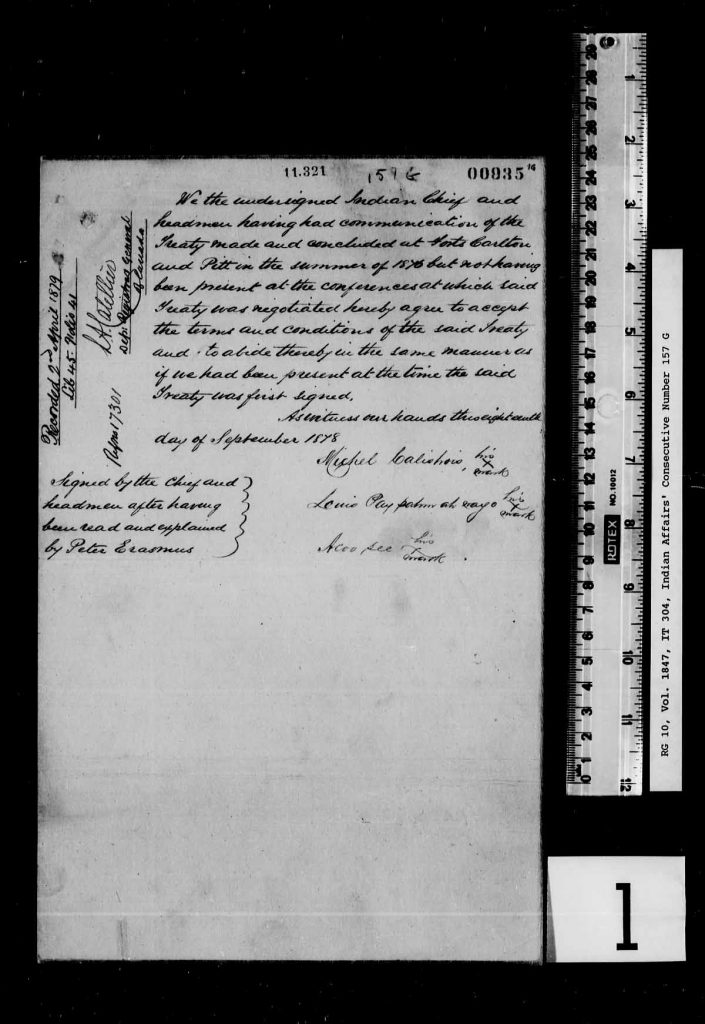

In terms of Amiskwaciwâskahikan, it lies within Treaty No. 6 territory, which stretches from the foothills of the Rocky Mountains to the Western borders of the province of Manitoba. There are over 70 First Nations that reside within the Territory, ranging from a myriad of language groups including Dene, Sioux, Cree, and Anishinabae. The terms of the Treaty were negotiated at Pêhonân, or Fort Carlton, the place where they waited to make Treaty, on August 23, 1876. Following the format of previous numbered Treaties, Treaty No. 6 included specific concessions requested by leadership influenced by events of the time and promises made by the Treaty Commissioner Alexander Morris, of the most well-known is the Medicine Chest Clause.

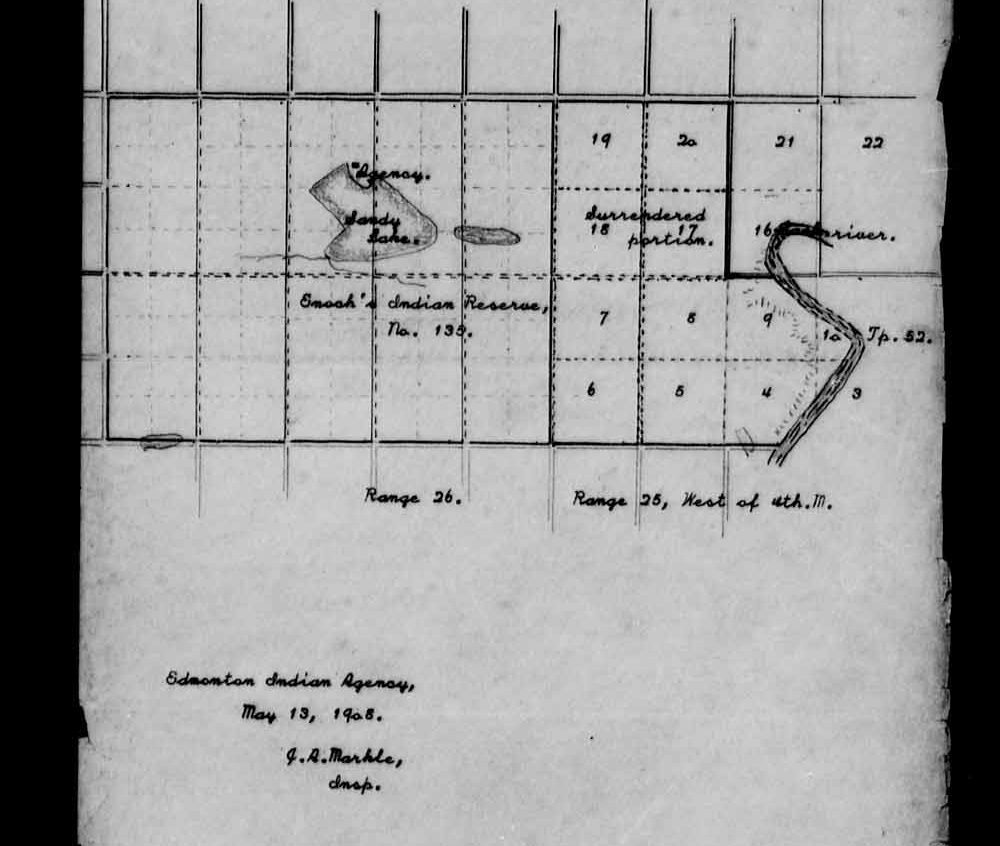

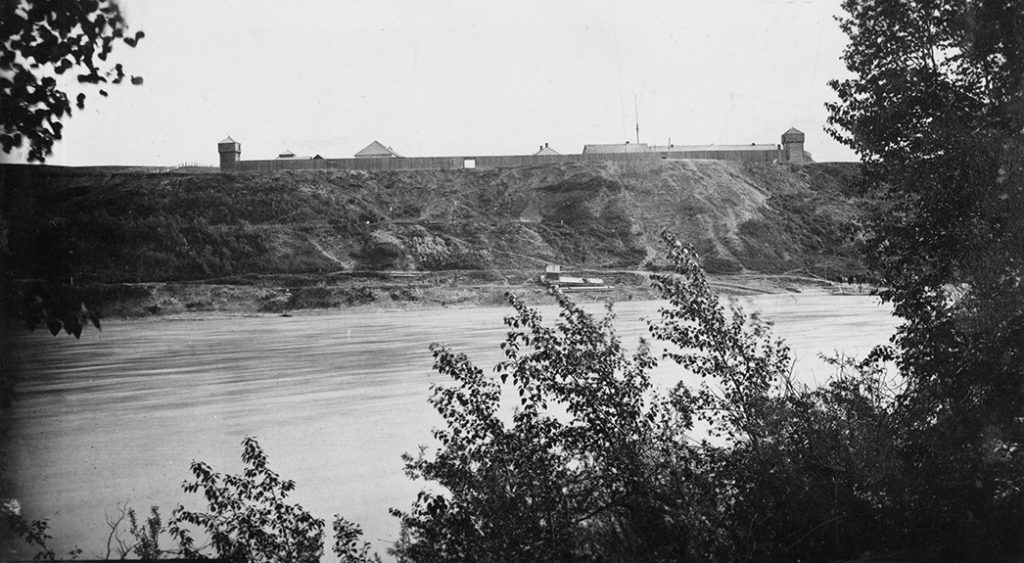

Adhesions took place on August 21, 1877 for six Chiefs including Alexis Kiskicihcîs (Keeskeecheechi), Omôsisinîy (Oomusinahsoowawsinee), Cacâstawaskam (Catchistahwayskum), Kosawanaskayo (Koosahwanaskayo), Pahpahcîs (Pahpashchase) and Takoc (Tahkootch), at Fort Edmonton. Hudson Bay Company Journals tell of an impoverished, starving people awaiting adhesion to these foundational documents. Beginning on August 6, 1877, the Fort began recording that “a few Stonies came along begging for grub”, and again on August 8th, “about 20 Stonies arrived they brought a few fur [and] some on a begging tour”. Statements such as this further highlight the lack of resources due to the depletion of the buffalo, and the emphasis required on adhering to Treaty.

As the summer of 1877 continued to drag on, “the Indians [continued] coming in one after another””… “flocking in every day for their annuities”. On August 18, 1877, M. G. Dickieson, the commissioner appointed to deal with Treaty No. 6, began to camp at what was known as the Barracks, which could be todays Ft. Saskatchewan. In a very business like approach, the recorder stated, “[Dickieson] will be up on Monday”. Further details were included in the August 19th entry, stating that Dickieson and Colonel Jarvis would be arriving from the Barracks, the former paying off the Indians, whom were arriving from all quarters. According to the archival documents, with the arrival of David Laird, formal payments began on August 21, 1877 with the St. Anne and Lac La Nun Stonies being paid off. With the annuity payments came increased commerce within the Fort, those present attempted to barter with the Indigenous peoples and some eventually selling horses to the tribes.

On August 22, 1877, Pigeon Lake tribes arrived for payment of annuities and adhesion to Treaty. The following day, Dickieson completed the payments of annuities and headed back to Battleford. The anticipation and emphasis on the event waned as the days passed and representatives of the Crown continued to leave. By August 25, 1877, “The Stonies left to their destinations” and the very business approach of Treaty, taken by those in the Fort, subsided and the daily grind resumed. Both parties would leave this momentous occasion with different interpretations and experiences. Indigenous leaders would go on to understand the process as an entrance into a sacred covenant with a respected and unquestionable Queen Mother. Non-Indigenous would interpret the process as a simple business transaction, no less important than a “paying off”.

Neither perspective is necessarily inaccurate in regards to the lens applied, however one cannot negate the spiritual aspect of the process that elevates beyond the two world views. In this sense, it is important for all to try and understand and interpret the covenants through the others lens. It is under this approach that engagements and projects like the Indigenous Peoples Experience at Fort Edmonton show great promise. By partnering with First Nations leaders and Elders, Non-Indigenous peoples can begin to explore how best to acknowledge this adhesion site as one of the key locations to the establishment of this territory. Until this happens, the adhesions of Treaty No. 6 in Edmonton will continue to exist in the hearts and minds of Indigenous people who retain the knowledge. Knowledge waiting to breakthrough the haze of skewed history and educate mainstream society on its spirit and intent.

Rob Houle © 2016

Sources:

Hudson Bay Company Archives File No: B.60/a/40 fos.17-21.

Copy of Treaty No. 6 between Her Majesty the Queen and the Plains and Wood Cree Indians and other Tribes of Indians at Fort Carlton, Fort Pitt, and Battle River with Adhesions.