Before the decriminalization of homosexuality in 1969, the University of Alberta’s queer community was similar to those everywhere else in Canada: closeted, underground, invisible. The closest thing LGBTQ students had to representation were academic panels where their professors discussed their deviance. “When little Johnny and George experiment with homosexuality, this does not mean they will grow up to be perverts, a panel agreed Tuesday,” notes a Gateway article from 1965. “The panel said homosexuality is not a mental illness; rather it is a personal problem… the perversion should be accepted by society, but it should be accepted like cancer is.”

In the fall of 1971, a young activist named Michael Roberts arrived in Edmonton. He set about establishing a chapter of the gay rights group he’d been involved with in Vancouver: the Gay Alliance Toward Equality (GATE). Although not strictly a student organization, GATE’s headquarters were campus-adjacent and its 15 members were mainly students and faculty members. Meetings and social events took place off-campus, but members of GATE organized discussion panels at the university and visited classes as a kind of queer show-and-tell (meet a real live homosexual!).

In its early years, GATE was predominantly a gay male organization. This was due in part to the establishment of lesbian feminist groups like Womonspace, but also because of its controversial poster featuring two naked men. The posters were continuously torn down and defaced, so GATE members continuously printed more and put them back up, refusing to be made invisible. The design was eventually changed to show two androgynous figures, and one of the new lesbian members suggested mixing condensed milk in with their flour paste, which cemented the paper to the walls for weeks.

GATE was never an activist organization, but many of its members engaged in political activity. In 1978, they protested notorious anti-gay bigot Anita Bryant when she visited Edmonton. This protest prompted the spin-off of the Edmonton Lesbian and Gay Rights Organization (ELGRO), a short-lived group which was the first queer organization to register as an official student club. GATE migrated across the river in the late 1970s (eventually becoming the Pride Centre). Its departure and the implosion of ELGRO left a vacuum at the U of A—space which would be filled by its first true queer social group.

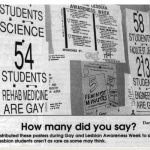

In September of 1984, 75 students formed GALOC: Gays and Lesbians On Campus. Their first major initiative was the publication of The Pink Triangle: a queer-oriented Gateway supplement which included articles on queer Christianity, being gay and Asian, and how to be a straight ally to LGBT people, among other topics. The following year, GALOC launched Gay and Lesbian Awareness Week (GALA), the U of A’s first pride celebration. The festivities were small—a screening of a Harvey Milk film, an info booth in HUB—but they generated a lot of attention. By 1990, GALOC’s annual membership had grown to over 100 students. GALA had become an understood tradition. And then on March 15, 1990, GALOC asked students across campus to do one simple thing—and everyone lost their minds.

For the fifth annual GALA week, GALOC requested that all students who believed in the equality of their LGBTQ peers wear blue jeans to show their support. The backlash was instantaneous. A number of openly bigoted students went nuts that the gays should have the temerity to choose such a mainstream piece of clothing as their symbol. Even those students who claimed to support gay rights complained that they felt manipulated into showing this support against their will.

In effect, GALOC forced people to stop sitting on the fence. You couldn’t just carry on as usual, ignoring GALA week but saying you supported gay rights. You had to make a choice: wear your blue jeans as usual and be a visible ally, or wear something else and reveal your true homophobia. This ultimatum made people furious. More importantly, it made the entire campus think about and talk about gay and lesbian rights for one day—something that had never happened before, and hasn’t happened many times since.

GALA week would’ve kept rolling merrily along if it weren’t for one sticking point; GALOC’s bisexual members were tired of being sidelined. In 1993, they forced the group to change GALA into B-GLAD: Bisexual, Gay, and Lesbian Awareness Days. This led to the inevitable conclusion that the name “GALOC” itself was not inclusive enough. So on its tenth anniversary in the fall of 1994, GALOC officially rebranded as LesBiGay UofA (say it aloud and hear the groan-worthy pun). Nobody really liked LesBiGay, so its members reconvened in the new year and negotiated a name that everyone could live with: OUTreach. The U of A’s current queer student group came into being at a magical moment. A 1995 article remarked on “an explosion of queer groups” on campus, including the Edmonton Vocal Minority choir, the Front Runners track club, and the Queer Academy coalition. Over the years, OUTreach expanded B-GLAD to include a kissing booth, the Queers At The Top party in RATT, and drag races across quad. Starting in 2002, they organized an annual drag show performance and fundraiser called Gender Bender at the Powerplant. After lapsing for a few years, B-GLAD was revived as Pride Week on campus in 2013.

Today, LGBTQ+ students enjoy a multitude of services, community spaces, and social groups at the U of A. But no matter how they organize themselves, generations of queer students have made sure that they will always be visible on campus—adding rainbow hues to the green and gold.

© Bruce Cinnamon 2015