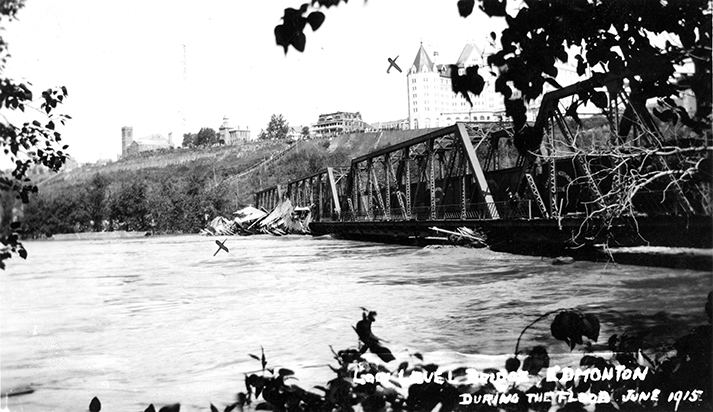

On June 29, 1915, the North Saskatchewan River flooded Edmonton’s river valley. The river had flooded before, of course, but a few factors increased the impact in 1915. Not the least of these was the sheer volume of water rushing down the river. At the its highest point, the Edmonton Bulletin estimated that the river rose to over 42 feet above the low water level (four feet higher than the flood of 1899, previously considered the worst flood in Edmonton). Impressively, the waters began to rise an estimated one foot per hour on Sunday the 27th of June. While thankfully there were no recorded lives lost or serious injuries sustained, by the time the flood began to recede, irreparable damage had been done, and the face of Edmonton’s river valley had been changed forever.

The events surrounding the flood tell us a great deal about what Edmonton looked like in 1915. For example, the Bulletin reported that tens of thousands of people (many of whom had lost their homes in the flood) stood at the top of the valley to watch the disaster. Picturing the number of people watching from the banks, we can also picture the size of Edmonton’s population in 1915. Edmonton was a sizeable city, with a population of just over 59,000, but tens of thousands of people would have represented a very sizeable portion of the population.

We can also look through the lens of the flood to understand industry in Edmonton in 1915. The river valley had developed considerably since the flood of 1899 to become a hub of industrial activity in Edmonton. It bustled with a variety of businesses that had successfully set up shop, including coal mines, brick yards, lumberyards, gold mines, breweries, and boat builders. The Bulletin remarked that none of these businesses carried flood insurance, with insurance providers either being unequipped to provide it, or finding so little interest in Edmonton that they could not provide it.

Small neighbourhoods of working class homes also peppered the valley, with workers wanting to live close to employment. By the time the flood was over, 2,000 Edmontonians had lost their homes, with 700 houses severely damaged and 50 swept away completely. Most of the people who lost their homes were members of Edmonton’s growing working class, and could hardly afford replacing their homes and belongings.

The damage to the businesses and homes on the river valley was estimated by the Bulletin to total three-quarters of a million dollars, all without flood insurance. Those who had invested heavily in river valley businesses saw enormous losses. John Walter, who had been made wealthy by his river valley investments, saw the total destruction of his lumber business, ruining him financially. Walter was quoted by the Bulletin as saying he expected the flood waters to recede far earlier than they did, and one of his neighbours later remembered Walter repeating as the flood progressed that “it’ll nae come o’er the banks”. It would be rare today to find businesses and homes in the valley without flood insurance, but in 1915 it just wasn’t considered necessary.

Further, we can understand advances in technology by looking at what conveniences Edmontonians missed after the flood. As a result of the disaster, the Rossdale Power Plant flooded and the Waterworks Plant also ceased operations. The Bulletin reported that “apart from damage to property, the most serious blow to the city was the complete cessation…of the power, water, and light service…Citizens had to go to bed by the aid of candles”. Many people, when trying to imagine what 1915 would have looked like technology-wise, would guess that going to bed by candlelight was a daily occurrence for most people. Not so! The fact that the Bulletin reported the lack of access to power, water, and light as the most serious blow aside from property damage, tells us how important these technologies had become to Edmontonians in a relatively short period of time. The outcry, in fact, sounds much like what it would be today if similar outages occurred.

Today, we don’t have many homes or businesses directly in the river valley, but at the turn of the twentieth century, city planners saw no reason to give up valuable industrial space with access to a vital waterway. In 1907, architect Frederick G. Todd wrote to the Edmonton City Council and the mayor of Strathcona that “perhaps no one thing is more important for large cities or cities which are assured of a great future than that they shall early secure open spaces for the benefits of future generations”. The open space that Todd had in mind was the river valley. Council saw the space as vital to industrial development, though, and in a rapidly growing city this seemed indispensable. Todd’s suggestion was largely ignored until the devastation of the flood.

After the flood of 1915, however, city officials started to pay more attention to the idea of a mostly empty river valley. Later in 1915, the Alberta government moved to adopt Todd’s line of thinking in principle going forward. By 1933, Edmonton had established zoning bylaws to protect the valley from industrial development. Today, we have the largest continuous stretch of urban parkland in North America, with our river valley encompassing over 7,400 hectares of land. This open land allows for enjoyment of the beauty of the river valley, but it also shows respect for a river that’s liable to flood. The North Saskatchewan has jumped its banks in Edmonton 20 times in the last 150 years, and the open space serves as important protection for the city when this happens.

After the severe floods during the summer of 2013, the government of Alberta banned future developments in the province’s floodways–the areas of land most susceptible to “100 year floods” (floods that tend to happen in the area every 100 years). While Edmontonians have largely avoided building in these floodways since 1915, some parts of Rossdale and Riverdale are in the fringe zone area, and some newer condominiums in Cloverdale were recently built right in the floodway.

The flood of 1915 was vital to the process of shaping Edmonton into the city we know today. Our river valley may not look the same, nor be under the same protections, had the flood not devastated it. In addition, we can also use the flood and the events surrounding it as a lens for understanding Edmonton as a city in 1915.

Watch a short documentary about the flood here. The John Walter Museum commemorated the flood on June 28.

© Sally Scott 2015