He established the practice of “neighbourhood unit” planning. And, borrowing a popular urban design feature from his native land, he implemented the city’s first dozen traffic circles, then known as roundabouts.

From its formative days, Edmonton had been designed on the grid system, with streets running north to south and avenues east to west. That system, with its block upon block of identical streets, made for easy route-finding, but also encouraged traffic to flow through residential areas.

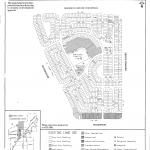

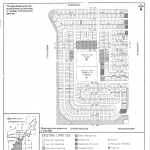

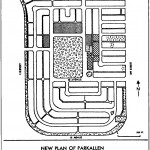

Dant introduced a “town planned” design approach with curvilinear street patterns leading to school and community league sites and green spaces at the heart of the neighbourhood. Crescents and cul-de-sacs replaced row-upon-row streets. Housing was a mixture of mostly single detached dwellings, with some rowhouses and low-rise apartments.

The design kept through-traffic away from the heart of the community, making the streets safer for pedestrians and reducing noise and air pollution. At the same time, the curvilinear street and laneway pattern was a more efficient use of land than the traditional grid pattern, but wasn’t so convoluted that visitors would get lost looking for an address. It also encouraged walking and social interaction.

Some of the first Edmonton neighbourhoods to be designed this way were Parkallen, Sherbrooke and Dovercourt. I grew up in Sherbrooke, and it was a fabulous place to call home. In those days, we used to play road hockey for hours on end, and seldom had to contend with cars because Dant’s design limited access points.

The neighbourhood has arterial roadways as its boundaries, with 118th Avenue to the south, 125th Avenue to the north, 127th Street to the east and St. Albert Trail to the west. That makes travelling to and from the neighbourhood easy and convenient.

Back then, the intersections at the northwest and southwest corners of the neighbourhood had Dant’s two-lane traffic circles. We used to marvel at their simplicity, and ability to move traffic counter-clockwise around a centre island without stops and starts.

There were always a few drivers (often from out of town) that couldn’t grab onto the concept that vehicles inside the circle had the right of way and how they could leave the circle safely once they were in it. Round-and-round-and-round they went like a carousel. When there were crashes, they were usually less severe sideswipe or rear-enders rather than head-on or T-bone collisions that occur at intersections.

Of the 12 arterial road traffic circles constructed in the 1950s, most had four entry and exit points, but the circle north of Bonnie Doon Mall had five. The one situated at the northern end of Princess Elizabeth Avenue at 101st Street and 118th Avenue was elliptical and fed by two additional local roadways. They’ve gradually been vanishing, replaced by interchanges and plain old signalized intersections.

When he came to Edmonton, Noel Dant brought with him not only lessons learned from his native England, where he studied architecture and town planning, but also a North American perspective gained from schooling on this side of the Atlantic. He graduated from Yale and Harvard and then went to work designing subway stations for the new Toronto Transit System and, in 1949, was hired as a Senior Town Planner for the Chicago Planning Commission.

That’s when the offer from Edmonton came to establish and lead the city’s first planning department. In 1949, Edmonton was a city filled with promise and the excitement of a prosperous future. He was just 35, eager for a new challenge, and Edmonton was it. The discovery of oil east of Leduc in 1947 and the post-war baby boom were stoking the engines of growth, and major industries were expanding and drawing workers by the thousands.

With cheap gas and lots of jobs, car ownership was exploding, putting plenty of pressure on road and transportation systems. Between 1945 and 1951, vehicle registrations in Alberta nearly doubled from 130,000 to more than 250,000. Edmonton responded with new roads and suburbs. Because the city owned much of the vacant land at the edges of the already developed neighbourhoods, it had control over new urban development from initial planning through sale and construction.

Through the 1950s, Dant’s formula was repeated in more than 40 inner-ring suburbs that were built just outside the city’s rectilinear core. Before long, Edmonton’s planning achievements were gaining professional acclaim, and Sherbrooke was cited by the American Society of Planning Officials as a model of good subdivision design. Planners across Canada began looking at Edmonton’s strategies and trying to emulate their success.

The Federal Building, completed in 1955, was originally slated to be built on land donated by the city at the west end of market square (where the Stanley A. Milner Public Library now resides), but Dant convinced decision makers otherwise. He envisioned a government centre stretching from the legislature between 107th and 109th streets north to 100th Avenue. History shows that his vision would be fulfilled.

Dant left Canada to work as a regional planning officer in Accra, Ghana, between 1955 and 1960. He returned to Canada then and became the Provincial Planning Director with the Department of Municipal Affairs until his retirement in 1979. Among his accomplishments was the outer ring road, which he convinced Edmonton City Council to adopt in principle in 1965.

He died in Edmonton in 1993 and in 2004 was named as one of the 100 Edmontonians of the Century.

© Lawrence Herzog 2015

Article header image:

Traffic circle at Groat Road and 111th Avenue and Westmount Shoppers Park, 1955.

Photo supplied by Inglewood Business Association.