In February 1943, the Soviet Union won the Battle of Stalingrad, turning the tide of the war on the eastern front. US and Allied troops retook the strategic island of Guadalcanal from the Japanese, a major tipping point in the Pacific theatre. Nazi Germany declared “total war” on the Allies, mobilizing its entire economy and society in reaction to defeats in the east and in North Africa. And Margaret Littlewood arrived in Edmonton.

The twenty-six-year-old Torontonian was an excellent pilot and flying teacher, with over a thousand hours in the air and an instructor’s licence from the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF).[1] But even with this extensive experience and a military-approved licence, the RCAF made no exception: it rejected women pilots out of hand.[2]

Some of these pilots—like Helen Harrison, who had 2,600 hours of logged flight time and was routinely passed over for men with less than 150 hours of experience—gave up on flying in Canada. Some were told that they could work as secretaries and cooks and telephone operators on the ground and joined the RCAF Women’s Division. Its motto? “We Serve That Men May Fly.”[3]

But Margaret Littlewood had another idea:

“I didn’t bother to apply to the RCAF because I already knew the answer … I didn’t want to let all that training and knowledge go to waste so I wrote to all ten of the Air Observer Schools (AOS), which were run by civilians. I said that I could relieve a man for other duties and suggested that I could be a flying instructor or a Link Trainer (instrument flight simulator) instructor. I received nine refusals.”[4]

Margaret got her tenth and final reply in January 1943 in a phone call from renowned WWI flying ace Wop May, who was in charge of Air Observer School (AOS) No. 2 in Edmonton: “How soon can you be out here?”[5]

Learning to Fly

Margaret’s love of flying began in 1938, when she was twenty-two years old. She was working an unfulfilling job in Eaton’s mail order department when she became friends with Marion Gillies, whose father Fred ran a flying school based at Toronto’s Barker Field. Fred took them up in a Piper Cub monoplane—Margaret’s first flight—and let her take the controls. She was hooked.

Margaret got her private pilot’s licence in August 1938 and earned her commercial licence in October 1940. In January 1941, she became the third Canadian woman with an instructor’s licence (Marion was the first).[6] Shortly thereafter, she started teaching at Gillies Flying Service full-time, and Fred turned over the management of the flying school to Margaret and Marion. They had a roaring business of men who wanted to join the RCAF, most of whom had no problem with a woman instructor.[7] In fact, Margaret and Marion received gifts from their grateful students, including boxes of chocolates and jewellery.

Unfortunately, everything changed in the fall of 1942. Gillies Flying Service was forced to shut down because of wartime fuel rationing, and Margaret found herself out of a job. Until, that is, one of her students suggested that she apply to the civilian-run Air Observer Schools, part of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan.[8] A few months later, she was on her way to Edmonton …

The Queen of the Link

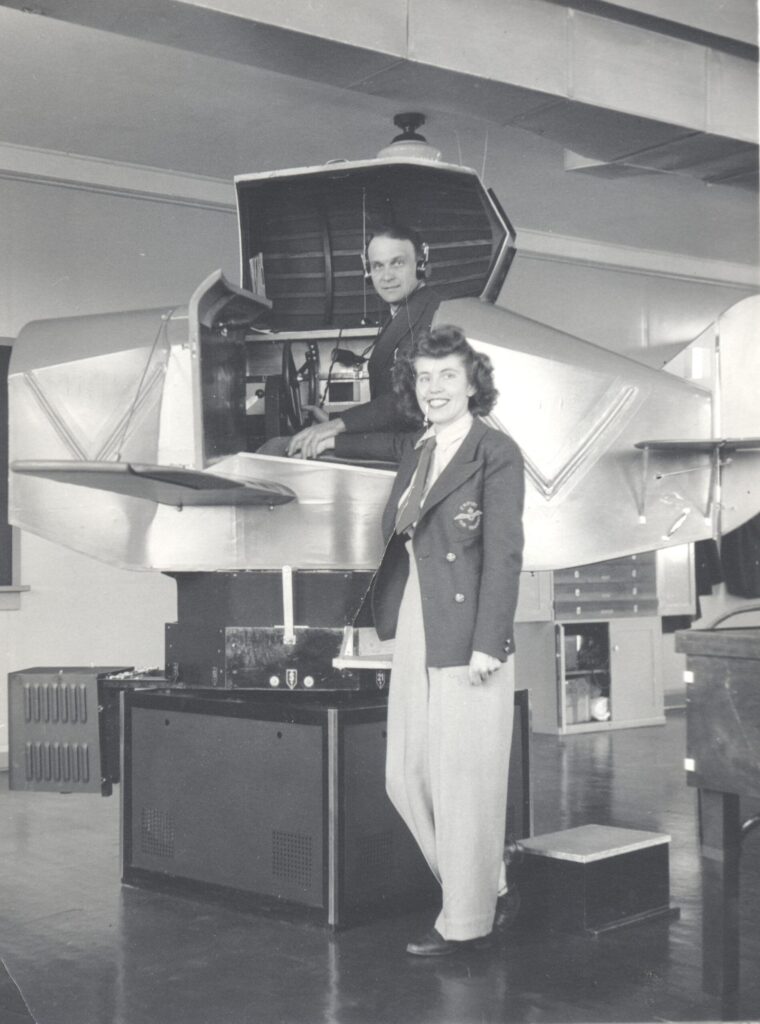

By the time she arrived in Edmonton, Margaret Littlewood had over a thousand hours of flight time.[9] But she had never used a Link Trainer, the flight simulator machine that she was going to be running for students at AOS No. 2—indeed, she had never even seen one.

She showed up at work on her first day confident in her skills, but nonetheless a little nervous. Those nerves were quickly brushed aside by the no-nonsense Wop May, who gave her a brief tour of the station and then dropped her off in the Link room to learn on the job.[10]

“He was not a man to dilly-dally with problems,” Margaret recalled. “He thought I was qualified and he didn’t care that I was a woman. He had always been an aviation pioneer and proved it again by hiring me: the only woman Link Trainer instructor in Canada during the war.”[11]

Wop May wasn’t afraid to go against the prejudices of the day when it came to building a qualified staff. He had also hired Albert and Cedric Mah, two Chinese-Canadian brothers who were rejected from the RCAF, as pilots.[12] He assured the experienced airmen that Margaret was “a highly qualified pilot” and even recommended her to speak at public functions. Reporters were pleased to feature this unique character and dubbed her the “Queen of the Link.”[13]

The Link Trainer itself was a sophisticated flight simulator for its time.[14] The aviation equivalent of a mechanical bull, it prepared pilots for dealing with a bucking airplane in difficult conditions.[15] It also taught them how to fly blind, using only their instruments to guide their aircraft.[16]

“The greatest satisfaction of my work was knowing every time I gave the signals and pointed out a mistake to the boys, that it might save their lives when they got lost coming home in bad weather,” Margaret recalled.[17]

Of course, it was not all fair winds at AOS No. 2. As the only woman pilot on the base, Margaret heard “her fair share of wisecracks and comments due to her gender,” and she learned that, before she’d arrived, “the men had laid bets that I was some old dame with a hatchet face and size twelve shoes!”[18]

Over time, however, Margaret won them all over with her “exceptional teaching skills and down-to-earth personality.”[19] She not only earned the respect of her male colleagues, but also became the favourite of multiple pilots, with one grizzled bush pilot phoning ahead to check that she was working before coming in to train.[20]

Over the next fifteen months, Margaret trained approximately 150 pilots on the Link Trainer, logging over 1,200 hours of training time.[21] She continued to learn not just about the Link, but also took courses in astral navigation and aerial photography—and even got to practise dropping an (inert) incendiary bomb during one of her many flights with the base’s pilots.[22]

After the War

In May 1944, AOS No. 2 closed, and Margaret transferred to Ferry Command in Dorval, Quebec, which coordinated pilots flying aircraft between North America and Europe.

After the war, her dream was to become a commercial airline pilot. But the airlines, much like the RCAF, refused to hire women pilots. Nevertheless, in 1949, Margaret decided to train with instructors at the Edmonton Flying Club and obtain the Public Transport Licence.

“It was the highest licence you could get, and I decided I was going to get it simply to prove to myself that I had what it took to become an airline pilot … It took me a year of studying and saving and I only got it through sheer stubbornness, knowing I could never use it.”[23]

Margaret was only the third woman in Canada to earn this licence.[24] She was asked by the Edmonton Flying Club to stay on as a part-time teacher, but she decided to quit flying in 1954 and instead went on to have a long career with the Ministry of Transport in Edmonton.[25]

In 1976, Margaret received the Amelia Earhart Medal from the Ninety-Nines (an international organization of women pilots set up by Earhart herself) for her important work on advanced flying training.[26] She may not have been able to break through all the barriers she wanted. But she left her mark on Canada’s aviation history. And the trail she helped blaze opened the door for other women – including Alberta-born Rosella Bjornson, who, in 1973, became Canada’s first commercial airline pilot.[27]

[1] Shirley Render, No Place for a Lady: The Story of Canadian Women Pilots, 1928-1992 (Winnipeg: Portage & Main Press, 1992): 28-29.

[2] Ted Barris, Behind the Glory: Canada’s Role in the Allied Air War (Markham, Ontario: Thomas Allen Publishers, 2010), 293.

[3] Barris, Behind the Glory, 77, 79.

[4] Barris, Behind the Glory, 79.

[5] Barris, Behind the Glory, 295.

[6] Jen Eggleston, “Canadian Aviatrix #61 – Margaret Littlewood (1916-2012),” Randomly Generated, updated May 24, 2022, https://randomlygenerated.ca/blogs/canadian-aviatrix-project/canadian-aviatrix-61-margaret-littlewood-1916-2012.

[7] Eggleston, “Canadian Aviatrix #61,”71.

[8] Barris, Behind the Glory, 294.

[9] Render, No Place for a Lady, 80.

[10] Major Bill March, “BCATP profile: Margaret Frances Littlewood,” Department of National Defence, Government of Canada, May 12, 2016, https://www.canada.ca/en/department-national-defence/maple-leaf/rcaf/migration/2016/bcatp-profile-margaret-frances-littlewood.html.

[11] Render, No Place for a Lady, 79.

[12] “Albert Mah,” Heroes Remember – Canadian Chinese Veterans, Government of Canada, last modified January 25, 2022, https://www.veterans.gc.ca/en/remembrance/those-who-served/chinese-canadian-veterans/profile/maha.

[13] Render, No Place for a Lady, 81.

[14] March, “BCATP profile.”

[15] “Link Trainer,” Alberta Aviation Museum, accessed, June 7, 2025, https://albertaaviationmuseum.com/collection/aircraft-collection/link-trainer/.

[16] “Woman Link Trainer Instructor Here, One of Only Two Believed in World,” The Edmonton Journal, June 22, 1943, 9.

[17] Barris, Behind the Glory, 296.

[18] March, “BCATP profile”; Render, No Place for a Lady, 80.

[19] Barris, Behind the Glory, 295.

[20] Barris, Behind the Glory, 296.

[21] Eggleston, “Canadian Aviatrix #61.”

[22] Render, No Place for a Lady, 80-81.

[23] Render, No Place for a Lady, 153-154.

[24] Render, No Place for a Lady, 154.

[25] “Margaret Littlewood Obituary,” Legacy, February 10, 2012: https://www.legacy.com/us/obituaries/legacyremembers/margaret-littlewood-obituary?id=44636442.

[26] Greg Sigurdson and Bill Hillman, “062 of 150: Margaret Littlewood – Link Trainer Instructor,” 150 Vignette Series – British Commonwealth Air Training Plan Vignettes, 2017, https://www.hillmanweb.com/150/13bcatp.html#62.

[27] “Rosella Bjornson,” Alberta Order of Excellence, accessed June 7, 2025, https://www.alberta.ca/aoe-rosella-bjornson; Margaret Littlewood was the only woman Link instructor in Canada during the war, but she was not the only “aviatrix” to make history flying in Edmonton. For more information about remarkable Canadian women pilots, check out No Place for a Lady: The Story of Canadian Women Pilots, 1928-1992 by Shirley Render (available for free on openlibrary.org). Or explore Jen Eggleston’s fantastic “Aviatrix Project” about The First 100 Canadian Women Pilots, which builds on Render’s research.