A common misconception is that Edmonton’s first Chinese settlers were fleeing an anti-Chinese mob in Calgary, centred around an incident involving a laundry worker with smallpox. In truth, they arrived two years earlier. But the true story and the myth both point to the importance of laundries in the lives of Edmonton’s first Chinese immigrants.

Cafes and laundries were common businesses for Chinese pioneers to start in Western Canada. After the completion of the Canadian Pacific Railway in 1886, many Chinese workers became unemployed. From 1872 and 1948, British Columbia [CC1] passed many discriminatory laws that prevented Chinese people from working in other railway companies, ferries, waterworks, gold gravel and drainage, dam and tunnel construction, mining, heating, and logging.[1] With few options, many Chinese workers were forced into service and labour jobs. Entrepreneurial Chinese pioneers started restaurants or laundries, and employed their fellow countrymen.

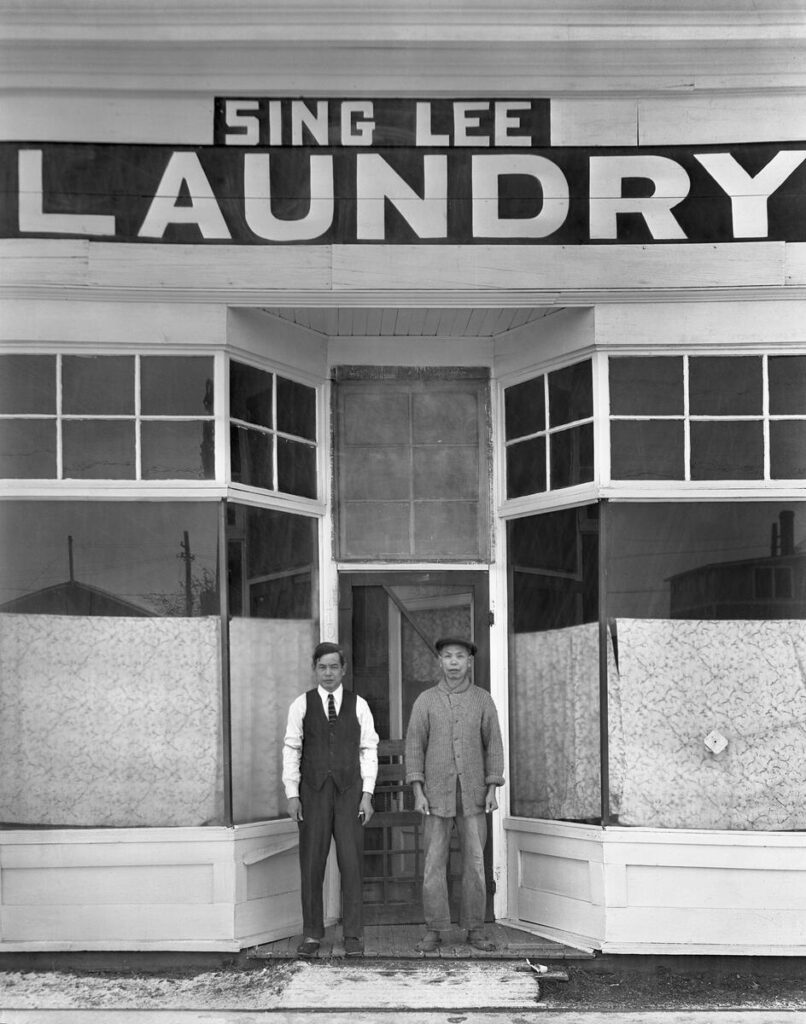

Laundries were relatively easy to start during this time, because they did not require a lot of money for expensive equipment. This was before the advent of washing machines, so everything was laboriously hand-washed. A successful operation only required dedication and a willingness for extreme hard work and harsh working conditions. Laundries could also be operated with relatively few English skills, as most of the transactions were relatively straightforward.

Life as a laundry worker was extremely difficult. Workers’ hands would always be blistered, burnt, or bleeding from all the soaking and scrubbing with boiling water, soap, and caustic chemicals. There were also many competitors in the laundry business, both white-owned and other Chinese businesses. Every laundry had to focus on providing fast and high-quality service, often at the expense of its workers. Laundrymen would work 16-18 hour days, seven days a week. The going rate for this work would be around twenty-five dollars a month.[2] For most workers, their entire existence consisted of only working, eating, and sleeping.

Inside most laundries, you would find a counter where a worker would handle pickup and dropoff of items. Customers would drop off large bags of dirty clothes, bedding, tablecloths, and napkins. These laundries were an essential service for many of the white bachelors in the prairies, since this was the only way to ensure clean clothes and linens. When customers came to pick up their clothes again, their goods would be folded neatly and wrapped in paper.

Edmonton’s first Chinese settler was a man named Chung Kee, also known as Chung Gee and John Kee. On May 26th, 1890, he arrived by stagecoach from Calgary, accompanied by a man generally assumed to be his brother, named Chung Yan.[3] Chung Kee started a laundry at 428 Jasper Avenue (now 9725 Jasper Avenue).[4]

Chung Kee’s arrival in Edmonton is often mistakenly linked to an event in Calgary known as the 1892 Smallpox Riot. On June 28, 1892, a Chinese laundry worker in Calgary was found to be recovering from smallpox.[5] Panic spread that the highly-infectious disease was being spread through laundry. That August, a mob of about 300 men assaulted Chinese residents and tried to burn down several Chinese laundries.[6] Some Chinese laundrymen left Calgary during this turbulent time, and two unnamed Chinese men moved to Edmonton.[7] Chung Kee is often mistakenly believed to have been one of these men, but he had already been established in Edmonton for two years prior.

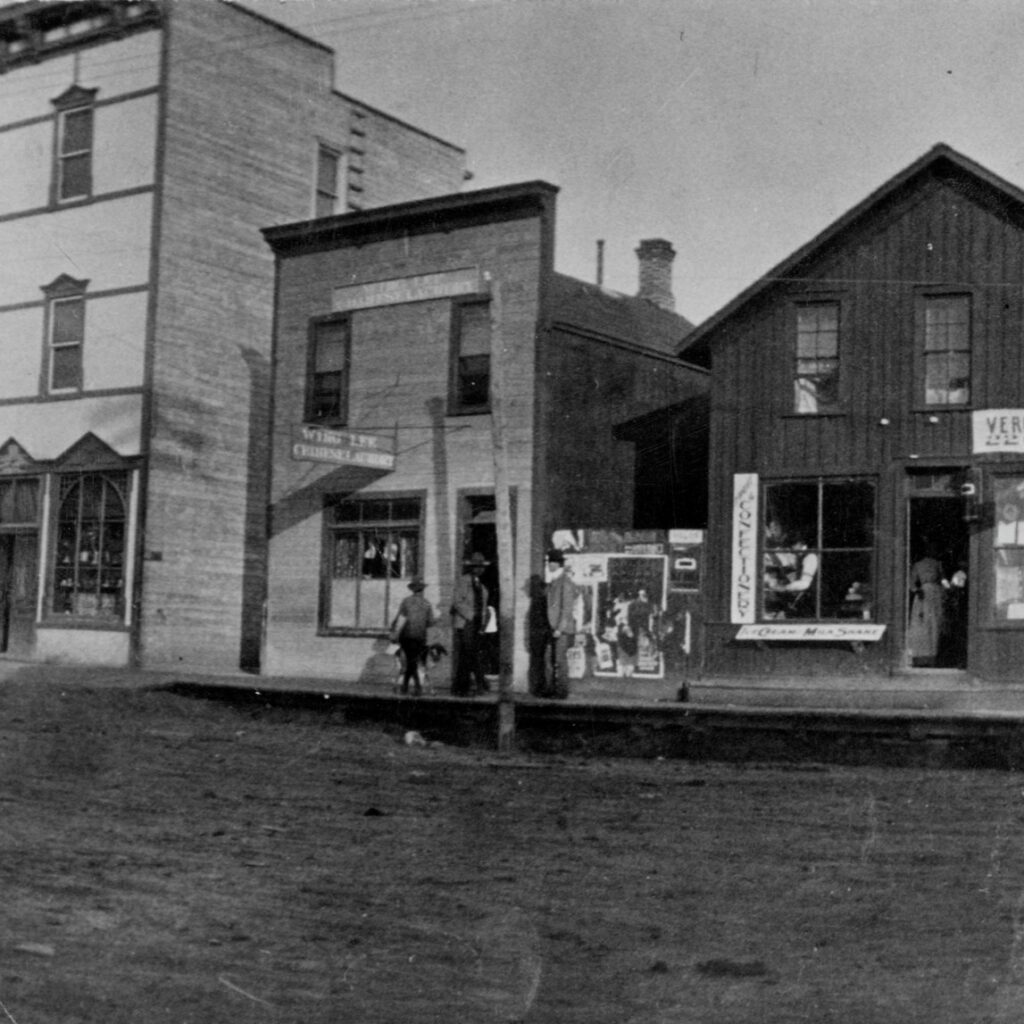

By 1911, there were 130 Chinese residents in Edmonton. Other hand laundries they ran included Wo Lee, Lee Sam, and Wing Lee Chinese Laundry. As the population grew, Edmonton’s first Chinatown formed on Rice Street (101A Avenue) between Namayo Avenue (now 97 Street) and Fraser Street (98 Street) on the edge of downtown.[8] This Chinatown would eventually be destroyed in the 1980s with the construction of Canada Place.[9]

Due to exclusionist policies like the Chinese Head Tax, it often cost an exorbitant amount for Chinese settlers to bring their wives and children to Canada. Chinatowns were often bachelor societies, and many of these bachelors worked in laundries as opposed to cafes where families could operate together.

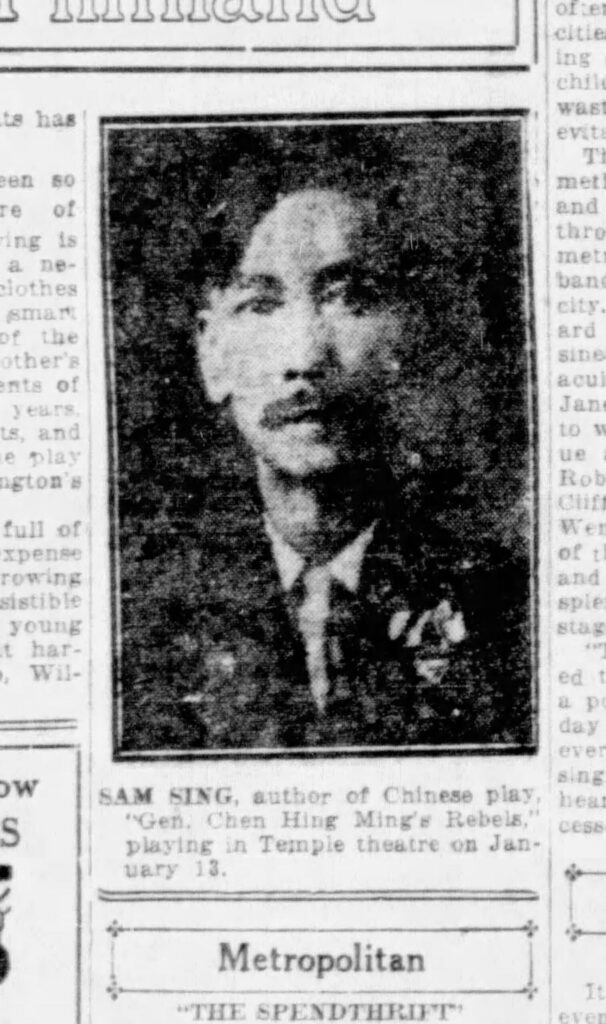

Another laundry was started by Sam Sing Mah (馬光珠) also referred to as Sam Sing, or “The King of Chinatown.” Born in China around 1864, he emigrated to Canada in 1889. A large and strong man who stood nearly six feet tall, he worked as a builder. He lived in Victoria for ten years, moved to Saskatoon briefly, and finally settled in Edmonton in 1899.[10]

“I established a laundry, which I later fitted up with modern machinery,” he told an Edmonton Journal reporter. “It was the first steam laundry in Edmonton.”[11]

In 1907, Sam Sing Mah opened up an import store called Kwong Lee Yuen (“Store of Big Profit”), which sold Chinese groceries and herbs at 9705 101A Avenue. This store also functioned as a gathering place for Chinese settlers. Throughout his life, he was known as an important community member for Edmonton’s Chinese community and a personal friend to many policemen, detectives, and judges. He was also a playwright and local president of the Chinese Nationalist League of Canada, an extension of the Kuomintang.[12]

In the early 20th century, Chinese laundries far outnumbered non-Chinese laundries in Edmonton.[13] But as steam-powered laundries gained popularity, Chinese hand laundries could not compete since most could not afford the technological upgrades. Hand laundries also could not survive for long with the eventual inventions of laundromats, home machines, and dry cleaners.

Due to the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1923, Chinese immigration was banned for a period of 23 years. This caused Edmonton’s Chinese population to decline steadily, and Chinatown on Boyle Street became depopulated and other stores and establishments took over.[14]

Even though Chinese hand laundries no longer exist today, they were a unique and integral part of early Canadian prairie settlements. Before 1940, a Chinese hand laundry could be found in almost every hamlet and town across Alberta. These services were invaluable to the greater frontier community, and should be acknowledged and celebrated.

[1] Helen Kwan Yee Cheung, Mercantile Mobility: Chinese Merchants in Western Canada (Edmonton: University of Alberta Library, 2022), 21).

[2] J. Brian Dawson, Moon Cakes in Gold Mountain (Detselig Enterprises Ltd, 1991), 62.

[3] “Local,” Edmonton Bulletin, May 31, 1890, https://archive.org/details/EDD_1890053101; David Chuenyan Lai, Chinatowns: Towns Within Cities in Canada (University of British Columbia Press, 1988), 92.

[4] Ken Tingley, “North of Boyle Street: Continuity and Change in Edmonton’s First Urban Centre,” Nov 2009, https://www.edmonton.ca/public-files/assets/document?path=PDF/5.6_A_BOYLE_RENAISSANCE_Historical_Review_final_FEB10.pdf

[5] Dawson, Moon Cakes in Gold Mountain, 29.

[6] Dawson, Moon Cakes in Gold Mountain, 31.

[7] Brian L. Evans, The Other Side of Gold Mountain: Glimpses of Early Chinese Pioneer Life on the Prairies from the Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection. (University of Alberta Libraries, 2010), 27. (“Edmonton Chinatown,” Edmonton Chinatowns 1900-2013, Simon Fraser University, https://www.sfu.ca/chinese-canadian-history/edmonton_chinatown_en.html

[8] Lai, “Chinatowns: Towns Within Cities in Canada,” 92.

[9] Wallis Snowdon, “Fighting for Change in Chinatown,” CBC News, CBC, Nov. 21, 2022, https://www.cbc.ca/newsinteractives/features/fighting-for-change-in-chinatown

[10] Dawson, Moon Cakes in Gold Mountain, 171.

[11] “Sam Sing Is Friend and Adviser To Edmonton Chinese,” Edmonton Journal, August 14, 1935.

[12] “Widespread Interest Is Being Evinced in Local Chinese Plays,” Edmonton Bulletin, January 11, 1923, 4. In the 1910s, a group of Chinese Edmontonians apparently formed an assassination squad to kill General Yuan Shikai, who had proclaimed himself the new emperor of China. Chinese National Party members in Edmonton considered it a betrayal of the 1911 revolution. In 1982, Toi-shan Society President Bing Mah said Sam Sing Mah may have been the one to ask for the squad’s formation. Bing Mah’s uncle was a member of this unit, which disbanded after arriving in Beijing in 1916 because Yuan was already dead. “Assassination squad trained here,” Edmonton Journal, November 12, 1982, B3.

[13] Dawson, Moon Cakes in Gold Mountain, 231.

[14] Lai, Chinatowns: Towns Within Cities in Canada, 92.

—

Special thanks for Connor Mah for assistance in finding images of Sam Sing Mah.