“Many times, we took three steps forward and five back…”[1]

How did a Royal Air Force (RAF) ground crew tech introduce computerization to the Alberta government? Bill Rogers had the right skills and serendipitous timing. He kick-started a computer revolution in provincial government work, which led to new career pathways dominated by women workers.

The Origins of Alberta’s Government Computer Programmers

It all began at Blatchford Field in 1945. The young Bill Rogers had put aside his accounting studies to serve in the war in England. He had experience with the RAF’s bombers, as a junior Aircraftman ground crew member, and was familiar with their computer systems.

A group of RAF personnel and computer scientists were stationed in Edmonton’s Siberia-like conditions to study air warfare issues. Bill set the scene:

“It was cold, and in the evenings, we would huddle around the heater in the barracks and talk. Some of the men were computer experts so we talked about the possibilities ahead for computers. It intrigued me and set off my imagination.”[2]

In 1948, having left the RAF, Rogers settled in Edmonton. He found a position to complete his Chartered Accountant (CA) designation where he articled for Keith Huckvale, the Provincial Auditor. By 1952, he had earned his CA and the Auditor’s ear.

Bill understood that it would be difficult to get computer programmers to understand government business needs. But the government could train its own workers to become programmers. Huckvale trusted Bill’s insight, promoted his idea, and appointed him as Director of Data Processing.

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, computers were behemoths. The mainframe computer comprised rows of data processing cabinets, containing hundreds of vacuum tubes, with data fed to them on hole-punched cardboard cards. Breakdowns were frequent.

The province already used mechanical accounting or tabulating machines to analyze data. A mainframe computer converted punched card data to magnetic tape. More automatic functions resulted in faster calculations.

Premier Ernest Manning approved the $1.25 million purchase of the IBM transistorized computer. The state of the art, room-sized equipment arrived in late 1961. Seventeen government employees, familiar with the processes of their departments, received five weeks of training in computer programming.

Between 1962 and 1969, Alberta computerized several aspects of provincial bureaucracy, including parts of the Motor Vehicles Branch and the Alberta Health Plan system. In 1970-71 the Alberta government digitized the production of Hansard, the daily record of proceedings in the Legislative Assembly, changing the turn-around time from three months to twenty-four hours.

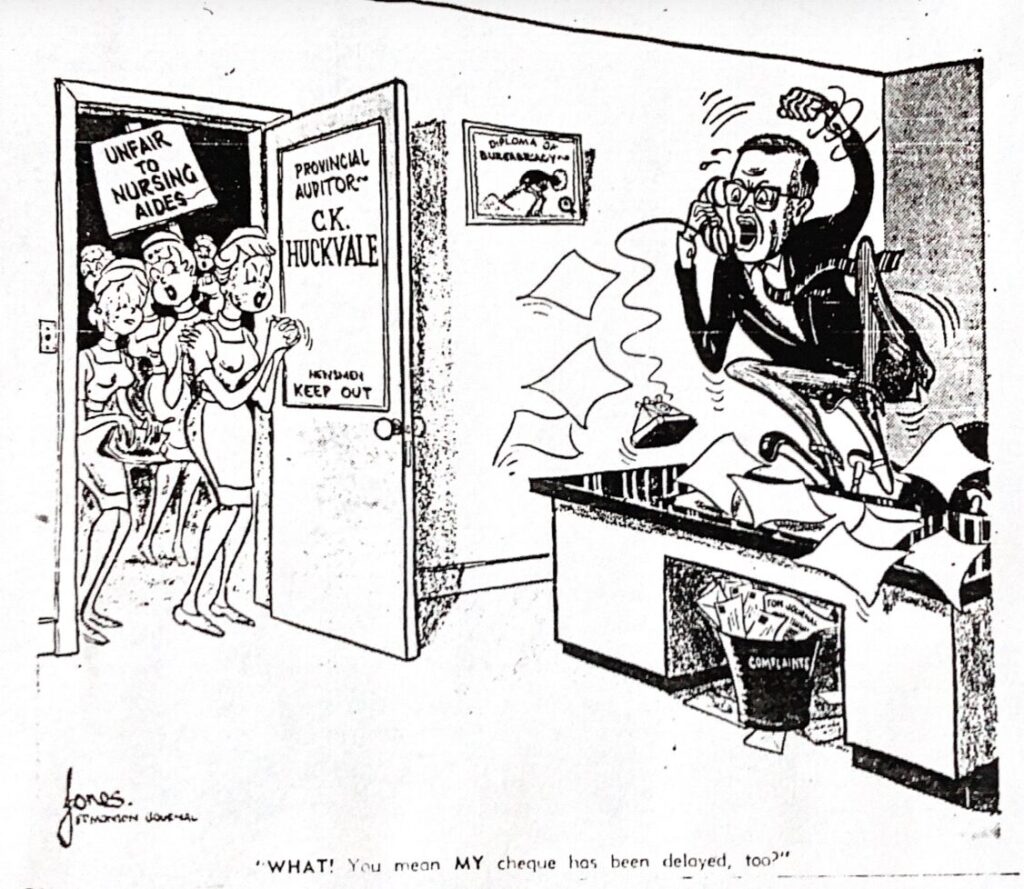

There were glitches in converting the civil service payroll from one cheque per month to two. Programmers were reported as working 24/7 to fine tune the system.[3] Auditor Huckvale denied that any payroll cheques were late.[4]

Computerization Depended on Women’s Labour

But programming is only half the story. A computer is useless without someone to enter the data. Who made those keypunched cards? The government recruited typists to operate the new machines, copying information from paper records onto punch cards. These workers were all women.

June Coljee worked as a key punch operator.[5] The women clocked in at the beginning and clocked out at end of each shift (8:15 to 4:30) and for bathroom breaks. On Wednesdays, they stayed until 9pm to help with the ever-increasing workload, as more government business was converted to the computer. By 1972, these workers had mandatory overtime of twenty hours per week. If you didn’t want to work such long hours, you were out.

The government also had special rules for women workers. Single women had a one-year probation period with no pension status then entered a women-only pension plan. If they married, they were not eligible for a pension. That rule changed in 1966, possibly to increase the number of contributors to the general pension plan.

Pregnancy was against the terms of employment, so most women tried to hide their pregnancies with clothing choices. One worker told of how she had casually mentioned another’s pregnancy at coffee break and realized with horror that she could have caused the dismissal of her colleague. The rule led to a sense of alienation rather than the usual comradery of a workplace.

The key punch operators worked in a factory-like setting. Despite the manager fighting to keep the eight-hour day, the new, larger key punch facility was staffed in two twelve-hour shifts. Key punch operators were selected for personality characteristics that predicted loyalty to a boring, stressful job – “punctuality, flexibility, responsibility and general intelligence.”[6]

Card trays of 3,000 cards were passed to workers and back to key punch “verifiers” for checking. It was very easy for the supervisor to track how productive each worker was. Workers with an error rate less than 2% were paid a monetary bonus, Cornelia Hagans reported.[7] But the reward amount was reduced for time on the job. This bonus system prevented talking on the job. But the noise of over 100 clanking key punch machines and later, the noise of the tape drives, made conversation impossible!

An article in the Harvard Business Review at the time reported that key punch operators were “nervous wrecks.”[8] Tranquilizers and aspirin were kept at workstations. Joyce Majnarich, the Alberta data centre manager, reported that the staff turnover rate was “horrendous.”[9] There was little room for advancement. The data centre of over 150 workers had one floor supervisor who held the position for over thirty years.

Joyce’s Story: From Cashier to Data Centre Manager

Joyce’s story is revealing. She started with the Provincial Government as a cashier, selling licence plates and renewing driver’s licences in the Motor Vehicles Branch in 1958. Joyce learned to operate a tabulating machine, became a key punch operator, and soon, the supervisor. In 1960, a memo came around the office asking if anyone wanted to train as a computer programmer. Joyce jumped at the chance.

Joyce became the assistant manager of the data centre and eventually, the manager. This was controversial; women were usually confined to the clerical ranks. She credits her personal ambition and Rogers’ forward-thinking ways.

From this position, Joyce saw the work environment in a new way and set about improving working conditions at the data centre. She insisted on applying scenic wallpaper and installing colour-coordinated light fixtures and machine covers, dividing the workspace by these coloured sections. She understood that a facility operating continuously had to be as visually pleasing as possible.

Despite the conditions, the workers interviewed for this history in 2006-7 remained proud of their work. They had pioneered the first use of a business computer in western Canada. Many of them were still in touch with each other decades after they had been colleagues on the project. A celebration, held in 1995, to honour the first programmers, saw 150 workers gather.

Today, 60% of people hold a powerful computer in their hands. Computer technology has progressed beyond military, scientific, and business uses. Individuals have become used to instant communications and access to information.

And men still dominate the computer field.

[1] Ralph Crouch, early programmer, quoted in Diana Coulter “At the dawn of the computer age, ‘It was so much fun’,” Edmonton Journal, October 21, 1995.

[2] Interviews with Bill Rogers, by Cathy Roy, December13, 2006 and January 3, 2007, at the Royal Alberta Museum. Bill lived from 1921-2013.

[3] “2 Alberta Computers Operate 24 Hours,” Edmonton Journal, April 16, 1962.

[4] “Auditor Denies Computer Late With Cheques,” Edmonton Journal, May 18, 1962.

[5] Interview with June Coljee, by Cathy Roy, May 24, 2007, at the Royal Alberta Museum.

[6] B. Van Weenen, “The impact of computers on office work”, in The Socio-economic Impact of Microelectronics, edited by J. Berting, S.C. Mills, and H. Wintersberger. Pergamon Press, 1980.

[7] Interview with Cornelia Hagans, by Cathy Roy, September 14, 2007, at the Royal Alberta Museum.

[8] I.R. Hoos, “When the computer takes over the office,” Harvard Business Review 38, no.4 (1960): 102-12.

[9] Interviews with Joyce Majnarich, conducted by Cathy Roy. May 4, May 24, and September 14, 2007 at the Royal Alberta Museum.

Bibliography

Cowan, Ruth Schwartz, “From Virginia Dare to Virginia Slims: Women and Technology in American Life,” Technology and Culture 20, no. 1 (1979): 51-63.