Oh, Geneva, here you are! I wondered if I was ever going to find you. I’ve never searched for a grave in the Edmonton Cemetery before, and the snow we had this morning covered up your flat granite marker, so I didn’t see it at first.

No gravestone ever reveals the breadth and depth of a person’s life, but I wanted yours to trumpet your accomplishments: first female professor at the University of Alberta, passionate Classics instructor, champion of women’s rights, adoptive mother. But all the inscription says is “Geneva Misener – Forever Loved in Memory – 1876-1961.” Someone even got the year of your birth wrong; you were actually born in 1877 in Wainfleet, Ontario, the second child and only girl among your four brothers.

The more I’ve read about the paths you blazed 100+ years ago, the more I’ve wished that your life hadn’t ended just as mine was beginning. I admire your determination to advance women’s rights and freedoms at a time when neither was assured. As we lose ground on some of the progress you made, the opportunity to chat with you would help me to learn more about the sources of your energy and persistence.

The University of Alberta hired you as its first female professor and advisor to female students in 1913, the same year it conferred its first degrees. You were thirty-six years old, armed with impressive academic credentials and extensive teaching and administrative experience. Eliza Fitzgerald, one of Canada’s first female university graduates, lit your passion for Classics when she was your teacher at Niagara Falls Collegiate Vocational Institute. In 1894, you followed her path to Queen’s University, where you earned a B.A. and M.A. in Classics and the gold medal in Greek and Latin. You headed to the University of Chicago to pursue a Ph.D., graduating summa cum laude in 1903 when you were twenty-six years old. Professors William Gardiner Hale and G.L. Hendrickson, whom you worked with there, commented on your “unusual” academic ability. The former praised your “brilliant” doctoral examination, and the latter predicted that you may “reasonably aspire to the highest positions available in this country.”[1]

I wish I could have attended one of your classes at Assiniboia Hall or in the newly built Arts Building. Dr. Paul Shorey, one of the professors you worked with at the University of Chicago, said that when you taught a summer class there on Greek history, you “awakened enthusiasm and retained interest of a class of teachers many of them much older than [your]self.”[2] I imagine you standing at your lectern, a woman “slightly built, with twinkling brown eyes and a quick, friendly smile,” intriguing your students with “the charm of classics, the hidden romance in old world life and customs, [and] the mysteries revealed by present day excavations.”[3] Maybe you told your students stories of your postdoctoral adventures in Europe. You studied at the University of Berlin and, “on horseback…penetrated desert sections of the old land,” attending lectures on archeology and visiting dig sites in Italy and Greece.[4]

Teaching Classics was not your only passion. You fought for women’s right to vote, to pursue higher education, and to combine a career and marriage. Not long after you arrived in Edmonton, you debunked the myth that women shouldn’t be allowed to vote because their literacy rate was lower than men’s. In fact, the opposite was true. You used your position as education convenor for the National Council of Women to promote lifelong learning. You criticized the view that, for women, marriage should take priority over pursuing a career. In 1919, at the first meeting of the Canadian Federation of University Women (CFUW), which you co-founded, you stated, “marriage and a profession may go hand in hand for a woman as for a man.”[5] At later meetings, you advocated for equal pay for equal work for women and men, and helped to establish a scholarship for academic women traveling abroad.

You were a living example that women are capable of balancing domestic responsibilities and careers. Although you never married, you cared for your mother in your Garneau home for fourteen years. You adopted your nieces when they were five and three years old and you were forty-nine, a brave and selfless step at a time when society frowned on single parenthood.

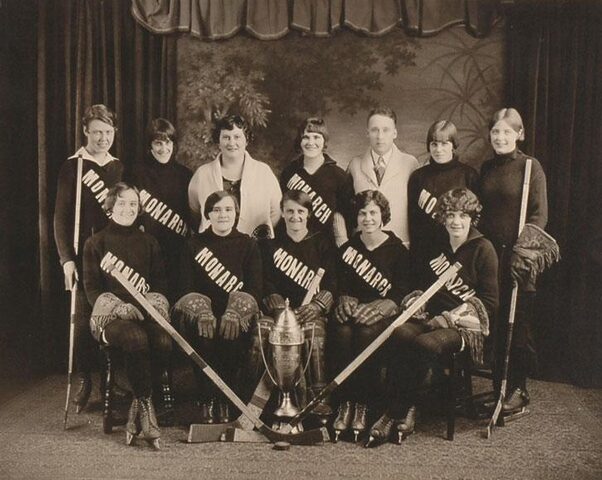

Who knows where you found the time, but you loved to skate, swim, golf, horseback ride, hike, and garden. As an advocate for women’s sport, you introduced women’s hockey to the Alberta Amateur Hockey Association in 1925. You became the Association’s first female vice-president, and donated the Misener Cup, the women’s hockey senior championship award.

Unfortunately, in 1943, a war-related upswing in technical, engineering, and medical programs contributed to declining enrollment in U of A Classics courses. You lost your battle with the University’s Board of Governors to maintain your academic position and moved to Vancouver after the war. Undeterred, you continued to deliver Classics-related talks in the community and to work with the CFUW. You were also involved with the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation, forerunner of the New Democratic Party, and researched public health in Canada. When you were seventy-three, you travelled around the world for eleven months, exploring social and political conditions in the South Pacific, Asia, the Middle East, and Europe.

I’m sad that your accomplishments have garnered so little attention in Edmonton, Geneva, and that so few tangible signs of you remain. Besides your gravestone, I found a small information marker on 90 Avenue and 110 Street in front of the empty lot where your home was located. Five scholarships have been established in your name, two at Queen’s, two at the U of A, and one through the CFUW. Yarniversity, an online knitting community run by sisters and U of A alums Cynthia Hyslop and Barb Barone, honors you with knitting patterns for a Geneva Misener vest, hat, and mitts. For Cynthia, hearing how one female academic fought for women’s rights and freedoms is “now more inspirational than ever. [But] paying attention to these [rights and freedoms] is a constant: we can’t take them for granted. ”[6] Perhaps your most important legacy for 21st century citizens, Geneva, is that when the odds of achieving change seem insurmountable, one person’s determination and positive action can make a difference.

Note: The headline quote is attributed to Dr. Geneva Misener quoting Dr. Paul Shorey, University of Alberta Archives.

[1] Dr. Geneva Misener, quoting William Gardeiner Hale and G.L. Hendrickson, University of Alberta Archives

[2] Dr. Geneva Misener quoting Dr. Paul Shorey, University of Alberta Archives.

[3] “Prof. Geneva Misener Sees Alberta in Lead of Adult Education Movement in Dominion,” Edmonton Journal, April 26, 1937; “Excavating excites interest in the Classics,” Edmonton Journal, July 27, 1931. https://www.newspapers.com/article/edmonton-journal-long-article-on-misener/150864824/

[4] “Ancient Romance for Excavators,” Waterloo Region Record, August 15, 1931. https://www.newspapers.com/article/waterloo-region-record-travel-and-urging/150524503/

[5] Katie Pickles, “Colonial Counterparts: The First Academic Women in Anglo-Canada, New Zealand and Australia,” Women’s History Review 10, no. 2 (2001): 288, https://doi.org/10.1080/09612020100200573

[6] Cynthia Hyslop, online conversation with author, December 2, 2024.