Editor’s Note: In December 2024, ECAMP presented a story from a former A-Channel employee who decided to cross the picket line during a strike there. Adrian Pearce – a former employee who helped lead their union local through the strike – submitted this story in response.

On the morning of September 17, 2003, as the strikers began spilling out of A-Channel TV onto Jasper Avenue, my feeling was anxiety. We were shaken and indignant with our treatment on the way out. Searched one by one as though we were common criminals. It was then that we realized that our relationship with our employer had changed and perhaps would never be the same again.

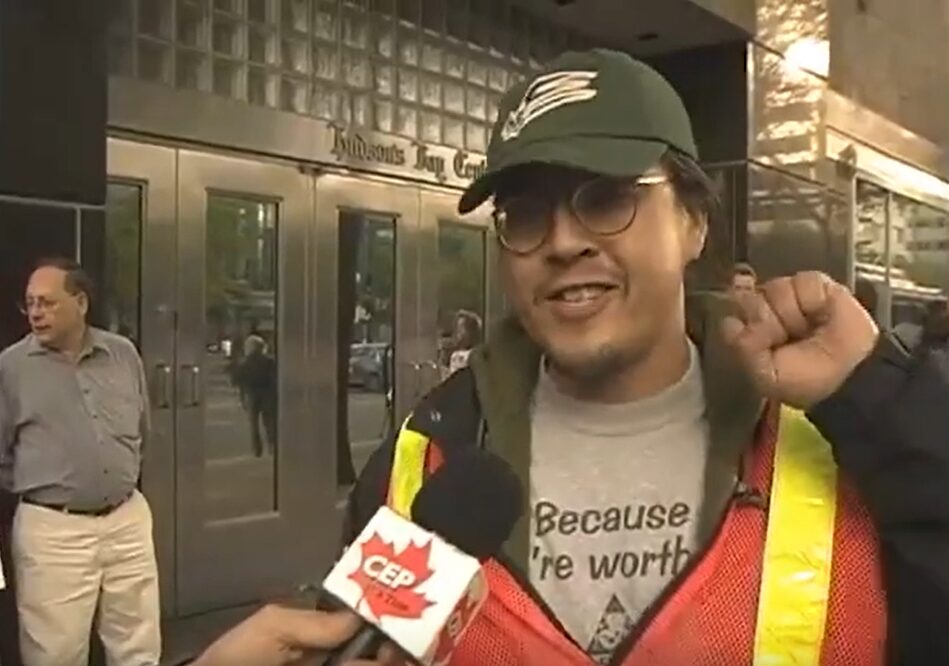

Our strike headquarters chairperson Alison Crawford had negotiated a space for us to use at Beaver House, across the street from the A-Channel parking garage. The disillusioned strikers made the short walk over there to begin picketing. A rep from the Communications, Energy and Paperworkers union had just arrived, armed with pens, markers, string and cardboard signs. Picket captain Shane Blyan soon had us at A-Channel’s front door and the strike was on.

That feeling in my gut lifted when I saw cameraman Nathan Gross wearing a picket sign that read “I CAN’T AFFORD A BIG BREAKFAST!” An ironic reference to A-Channel’s popular morning show. Seeing his sign made me laugh and I thought to myself that in spite of what might lay ahead of us, we were going to be alright. As the strike unfolded, the Big Breakfast lost a huge share of rating because all of us who made the show were out here on the picket line.

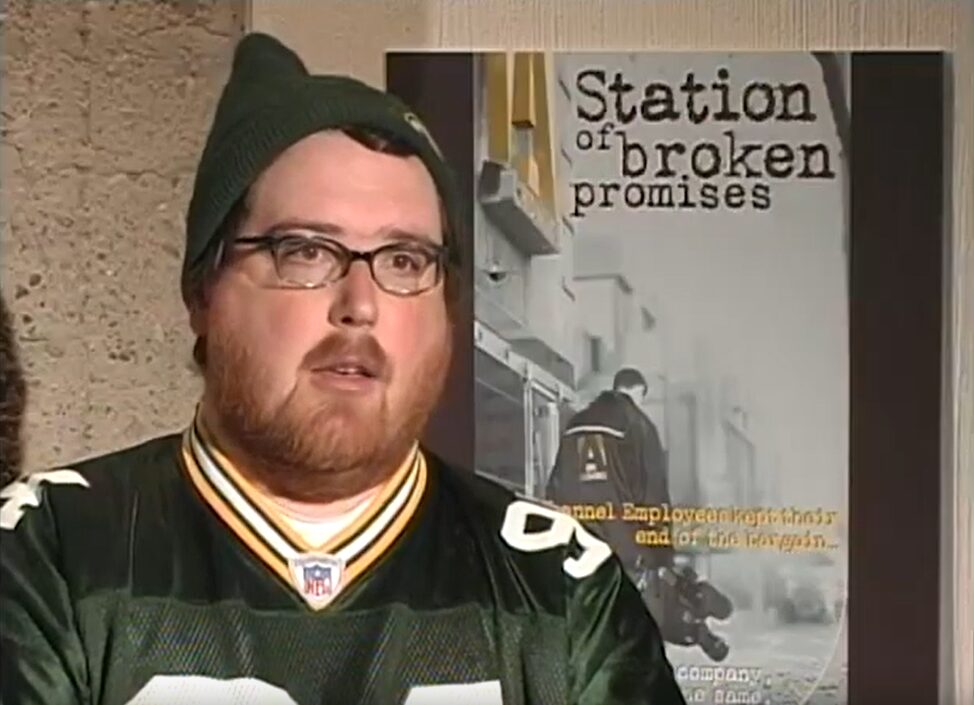

A year previously, in a scene right out of “All the President’s Men”, a news cameraman approached me in the dark, deserted station parking garage and said “I hear they’re starting a union here. What do you think of that?” He wanted to see which side I was on without showing his cards. I didn’t have to think. “We need a union! They way they treat people here is right out of the seventies!” In my short time at the station, I had witnessed managers yelling at employees and treating them like misbehaving children. I also discovered there was a caste system in place. A select few were paid higher wages, given time off to freelance and given preferential treatment that not everyone was entitled to have. Managers kept saying that wages and working conditions would improve, but after five years of waiting, some were calling it “the station of broken promises”.

They say the best recruiter for a union is bad management, so it was inevitable that A-Channel employees would organize. It was at a secret meeting with ten other employees that I understood what had to be done. I recognized Art Simmonds who I had worked with at CFRN as the union rep, and I knew him to be honest and a man of integrity. I knew then that I was going to be a part of this effort.

As we soon discovered, that was the easy part. CEP immediately applied to the Canada Industrial Relations Board for certification of approximately 100 employees. But the station’s owner, Craig Broadcasting of Winnipeg, wasn’t going to make it easy. They hired lawyers and a consultant to raise every objection possible to try to stop us. After 9 frustrating months, the Board issued a certificate to CEP.

Our group was relatively small so we became part of CEP Local 1900, which already represented workers at Global-TV and Corus Entertainment in Edmonton. I was elected chair of our unit within Local 1900 and a member of the local’s executive.

Bargaining dragged on for 16 months with the company refusing to even consider setting up a wage grid. This became a defining issue for our members and led to the eventual breakdown in negotiations. Despite the efforts of a federal conciliation officer, we were at an impasse. On September 11, 2003, union members voted to go on strike. Six days later, we were on the picket line.

The station immediately hired a strike-breaking company from British Columbia. We called them the “Goons!” They went intimidating us and recording our every move. They obtained court injunctions to stop us from picketing outside the parking garage or standing on the station steps. We were losing the legal battle.

But then, things began to change. I was invited to speak at a CBC union meeting and tell our story of the strike. When asked what we needed, I said we needed cameras so we could record what the strike-breakers were doing to us strikers. They donated enough money to cover the cost of 6 cameras and shortly thereafter, the tide began to turn for us. We filed an unfair labour practise complaint, detailing the strike-breakers’ bullying and provocation. We made our case with the help of lawyers Gwen Gray QC and Leanne Chahley who used video and other materials gathered by our smart strikers. Following a short hearing, the Canada Industrial Relations Board ordered the head of the strike-breakers to stay away from the strike. It was like cutting off the head of the snake and their power over us diminished significantly.

A-Channel’s daily broadcast was recorded every day by Gary Hart to find out which advertisers were still advertising on the station. We had many laughs watching the pitiful programming the station was producing without us.

We sent small teams to stand outside advertisers’ premises to distribute handbills to customers, informing them that the retailer was continuing to advertise on A-Channel. The effect on the station’s ad revenues was dramatic and greater than any of us expected.

By March 2004, it was clear that the station was suffering financially and many of our members were looking for progress towards a settlement. Management agreed to meet, and they finally accepted our concept of a pay grid that would over 4 or 5 years bring us up to comparable wages that workers were making at Corus Entertainment. We had a deal.

Going back into the station was a shocking experience. It was like going into a nightclub at night and then seeing the place in the light of day. Dog eared and shabby. The large windows looking out onto a busy Jasper Avenue were blocked off. The place looked like it had been under siege which I guess it had been for 166 days.

We followed the back-to-work agreement, but management did not. We were forced to work alongside replacement workers hired during the strike in violation of the back-to-work agreement. We filed a grievance and in arbitration, the station manager admitted that contravening the agreement was “a recipe for disaster”. A-Channel; was ordered to dismiss the replacement workers. No wonder we called the place “The Station of Broken Promises”.

All photos in this article courtesy of CEP History. Learn more from their A Channel Strike documentary: