The Alberta Penitentiary operated on Edmonton’s River Lot 20 from 1906-1920, where Clarke Stadium is today. It was the first federal prison in Alberta. Before beginning my research a few years ago I had no clue it existed, despite attending many football matches at Clarke Stadium over the years. People I have shared stories with have been surprised the Penitentiary existed. But they have been less surprised to hear of the appalling living conditions for prisoners.

It is difficult to tell the story of prisoner’s day-to-day lives using archival sources. In 1913 the Alberta Penitentiary held 206 prisoners. At this time, 195 prisoners were men and eleven were women. In total, 197 prisoners were identified as white, five as “negro”, two as “Indian”, seven as “Indian half-breed”, and one as “Mongolian.”[1] Theft was the most common crime prisoners were charged with, followed by manslaughter and murder.

Prisoners were not allowed to speak while in their cells. They were called by number instead of their name,[2] and were often punished during their prison sentence. A bread and water diet was one common punishment.[3] On special occasions prisoners were treated to celebrations with music.[4] One constant in prisoners’ lives was hard labour.

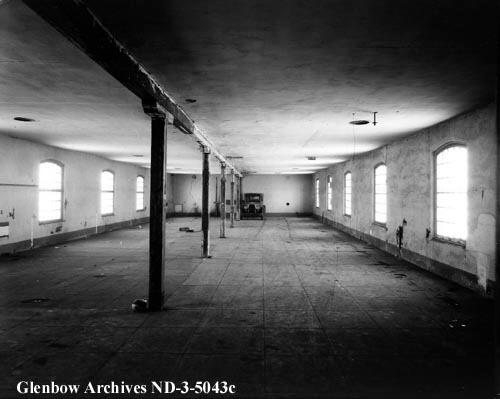

Forced labour was built into the Canadian prison system. According to the Inspector of Penitentiaries in 1915, unpaid labour of prisons was vital to the way prisons ran.[5] Forced labour was used to make many products which were sold to farmers, industry, or back to the government. Twine was one item produced by prison labour and sold to farmers for tying hay bales. Across Canada, penitentiary buildings were built by prisoners. An Edmonton Capital article from February 1911 details how the prison would be “one of the most up-to-date on [the] continent,” and glowingly reports that new buildings were “erected exclusively by convict labour”[6] using bricks and cement made by prisoners. In their reporting, local media positively observed that penitentiary labour was cheap and could be used to generate profit and useful products.

Farming was another type of forced labour. In the early 20th century, all Canadian federal prisons had a farm worked by prisoners. The Alberta penitentiary farm covered 45 acres in 1915, and prisoners prepared and planted another 35 acres the following year.[7] Prisoners farmed about 1500 acres across all prisons in Canada. From 1916-1917 the Alberta Penitentiary farm produced a net profit of $2,028 (approximately $40,000 CAD in 2025 money).[8] Prisoners grew a wide range of vegetables on the farm. These fed prisoners and staff, while extra was sold to local customers and stores. They also grew hay and green feed for livestock. A man named C. W. Brett oversaw the farm and many prisoners had previously worked as farmers before they were convicted of a crime.[9]

Many prisoners also worked in the prison’s coal mine. Coal was vital to the development of Edmonton’s economy. It was used to heat homes, power trains, and make household and industrial products. Prisoners began mining at The Penitentiary Mine in 1908, two years after the penitentiary opened.[10] Coal from the mine was used to heat the Alberta Penitentiary. It was also sent to the Stoney Mountain Penitentiary in Manitoba, and the Saskatchewan Penitentiary in Prince Albert. Excess coal was also sold to locals in Edmonton.[11] The Penitentiary Mine was vital to the federal prison system, providing coal for the heating needs of all three prairie penitentiaries. Large amounts of coal were available in the Penitentiary Mine. Warden Matt McCauley expected there was enough coal in just one seam to fuel the penitentiary for 25 years.[12] This was likely true. When the penitentiary closed in 1920, the site was valued at $1 million ($15.8 million in 2025 money) largely because there was so much coal left in the deposits.[13]

There was no shortage of coal mining work for prisoners. A prisoner who had previously worked as a minor guided the work during the first couple of years the mine operated.[14] After that, coal mining was supervised by the Chief Trades Instructor, John McDougal. During this time, anyone held in a federal institution was serving a sentence of at least 2 years for committing “major crimes”.[15] Prisoners at the Alberta Penitentiary were therefore thought of as quite ‘dangerous’ or ‘high risk’. When farming and mining, prisoners worked outside the walls of the penitentiary. Mining and farming labour was framed as a privilege given to well behaving prisoners.

While not all prisoners were put to work in the farm or coal mine, every prisoner had some type of job. Brick making, carpentry, blacksmithing, and stone-breaking were all common tasks. The latter was often used as hard labour to punish prisoners. Newspaper stories and government reports, framed prisoners as unproductive and immoral people. Forced labour was a way that prison officials wanted to “correct” them. According to Inspector of Penitentiaries Douglas Stewart, the role of prison officials in 1915 was to create a habit of hard work amongst inmates so that they would not commit future crimes.[16]

Even after it closed in 1920, the penitentiary became a site of a different type of forced labour. Some of the buildings were slowly taken apart through the 1920s and 30s to make way for sports fields. During the Great Depression of the 1930s, this work was done by city funded “relief labour” where unemployed and poor men were paid very little to do the physically demanding work of removing the large brick buildings.

Conclusion

The injustices of prison labour in Edmonton did not end when the Alberta Penitentiary closed in 1920. In 2025 Edmonton has one of the highest concentrations of prisons of major cities in Canada.[17] In their great book, Solidarity beyond bars: Unionizing prison labour,[18] Jordan House and Asaf Rashid argue that work as a moral good, and a way to produce profit, are still key ideologies behind the Canadian prison system. When the Alberta Penitentiary operated, prisoners were paid nothing. Now, prisoners are paid pennies per hour to produce products that are sold at a significant profit. This work is hard, demanding, and not desirable. There are about 3,400 spots for prisoners in and around Edmonton, and many of them continue to labour under forced conditions every day.

[1] Douglas Stewart, Hughes, W. S. Ministry of Justice, Annual Report of the Inspector of Penitentiaries (Ottawa: 1913), 111, https://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/lbrr/archives/csc-rmjpc-1913-eng.pdf.

[2] The Edmonton Capital, “Musical Program at Penitentiary” The Edmonton Capital, November 7, 1911, http://peel.library.ualberta.ca/newspapers/EDC/1911/11/07/7/Ar00709.html?printable=true

[3] Douglas Stewart, Ministry of Justice, Annual Report of the Inspector of Penitentiaries (Ottawa: 1915), https://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/lbrr/archives/csc-rip-1915-eng.pdf.

[4] The Edmonton Capital, “Musical Program at Penitentiary” The Edmonton Capital, November 7, 1911, http://peel.library.ualberta.ca/newspapers/EDC/1911/11/07/7/Ar00709.html?printable=true

[5] Douglas Stewart, Ministry of Justice, Annual Report of the Inspector of Penitentiaries (Ottawa: 1915), https://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/lbrr/archives/csc-rip-1915-eng.pdf.

[6] The Edmonton Capital, “The House of Correction” The Edmonton Capital, February 13, 1911, http://peel.library.ualberta.ca/newspapers/EDC/1911/02/13/3/.

[7] Douglas Stewart, Ministry of Justice, Annual Report of the Inspector of Penitentiaries (Ottawa: 1916), https://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/lbrr/archives/csc-rip-1916-eng.pdf.

[8] Douglas Stewart, Ministry of Justice, Annual Report of the Inspector of Penitentiaries (Ottawa: 1917), p. 6 https://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/lbrr/archives/csc-rip-1917-eng.pdf.

[9] Douglas Stewart, Ministry of Justice, Annual Report of the Inspector of Penitentiaries (Ottawa: 1916), p. 140 https://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/lbrr/archives/csc-rip-1916-eng.pdf.

[10] Taylor, Richard Spence. 1971. Atlas: Coal-Mine Workings of the Edmonton Area. Spence Taylor and Associates.

[11] Douglas Stewart, Hughes, W. S. Ministry of Justice, Annual Report of the Inspector of Penitentiaries (Ottawa: 1914), https://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/lbrr/archives/csc-rip-1914-eng.pdf.

[12] The Edmonton Capital, “Have A Coal Mine At Penitentiary” The Edmonton Capital, July 11, 1910, http://peel.library.ualberta.ca/newspapers/EDC/1910/07/11/5/Ar00502.html?query=newspapers|coal|%28date%3A1910%2F07%2F11%29+AND+%28publication%3AEDC%29|score.

[13] Edmonton Journal, “$1,000,000 Value Placed on Site of Penitentiary” Edmonton Journal, Sept 25, 1920, p. 7.

[14] The Edmonton Capital, “Have A Coal Mine At Penitentiary”, 1910.

[15] Douglas Stewart, Ministry of Justice, Annual Report of the Inspector of Penitentiaries (Ottawa: 1915), https://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/lbrr/archives/csc-rip-1915-eng.pdf.

[16] Douglas Stewart, Ministry of Justice, Annual Report of the Inspector of Penitentiaries (Ottawa: 1915), https://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/lbrr/archives/csc-rip-1915-eng.pdf.

[17] City of Edmonton. “Fiscal Gap: An assessment of factors contributing to the City of Edmonton’s operating and capital funding shortfalls”, 2024. https://pub-edmonton.escribemeetings.com/filestream.ashx?DocumentId=236515

[18] House, Jordan, Asaf Rashid. Solidarity beyond Bars: Unionizing Prison Labour. Fernwood Publishing, 2022.

Further Reading

House, Jordan and Asaf Rashid. Solidarity beyond Bars: Unionizing Prison Labour. Fernwood Publishing, 2022.

Pasternak, Shiri, Kevin Walby, and Abby Stadnyk, eds. Disarm, Defund, Dismantle: Police Abolition in Canada. Between the Lines, 2022.

Ormandy, M. Theft, Death, and Disappearance: The Alberta Penitentiary, 1906-1920. Active History. 2024. https://activehistory.ca/blog/2024/09/12/theft-death-and-disappearance-the-alberta-penitentiary-1906-1920/