“Leve! Leve! Et puis…hurrah!”! (Get up!, Get up! And then…hurrah!)

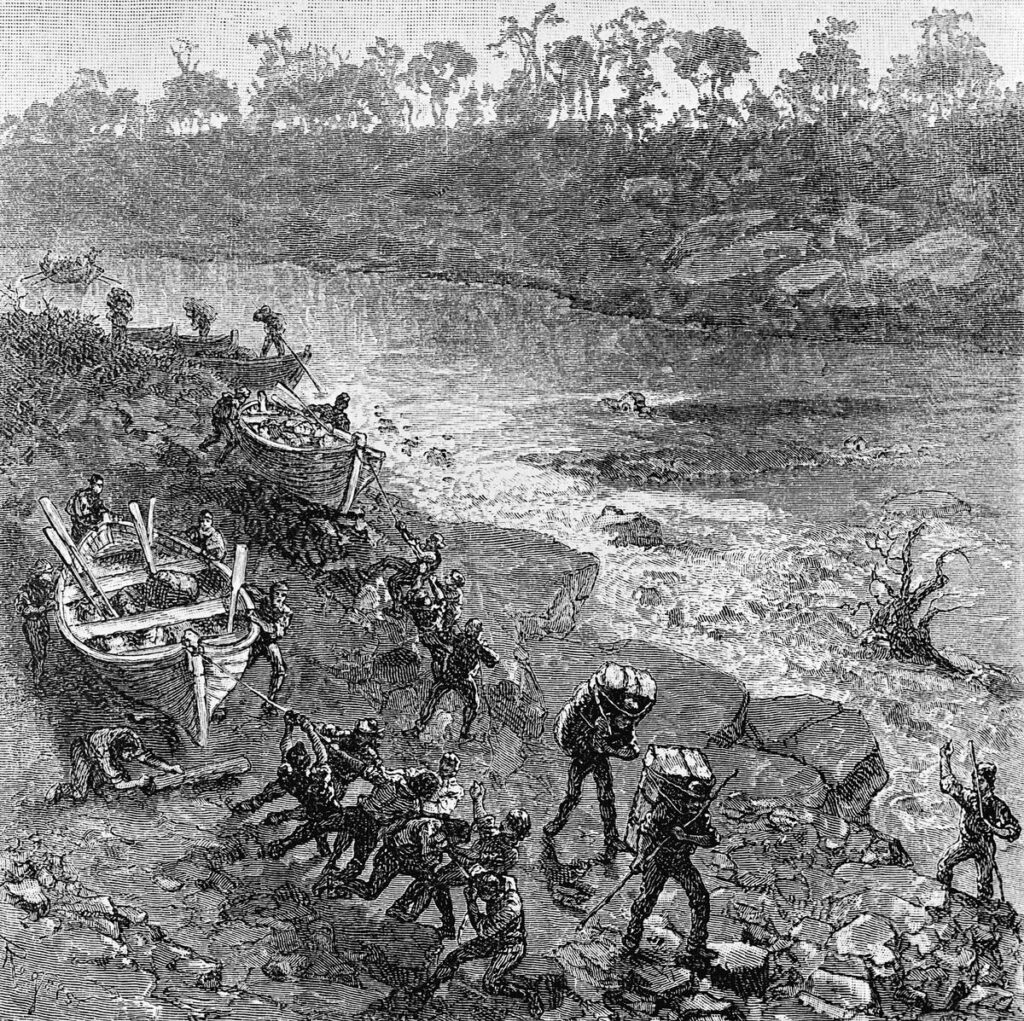

This was the call that roused the Hudson’s Bay Company’s Saskatchewan Brigade from their brief slumber, usually around 3am. It was another grueling day of pulling oars and carrying bales for the Badgers, or “Braroes” (for so the Saskatchewan Brigade called themselves), over portage. The furs they carried were traded for at Forts like Edmonton and rowed down the rivers to the Bay, before the Braroes faced the still-harder work of getting next year’s trade goods back up-river before the waters froze.

Courtesy of Library and Archives Canada 4105217

Leve! Leve! was the call that roused the Métis, Orkadians, and Canadiens[1] in the Brigade to work – but one can imagine it also rousing them to a consciousness of their power. A call to realize that the Company’s concern for profits would rarely, if ever, coincide with a concern for them and their wellbeing. Not unless they “got up” and demanded it.

In 1853, the Braroes shipping furs from Fort Edmonton combined their voices to argue with their superiors. It was called a Combination: not quite a strike, not quite a mutiny, but very much a show of strength and unity. The main issues in question: whether a labourer in debt to the Company was permitted to renege on his contract, and whether labourers had to pay to rent horses they used to do Company work.[2] On one side the Braroes, on the other the Company Officers – including famous Edmontonian John Rowand.

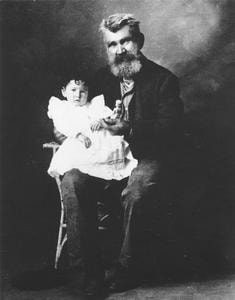

Courtesy of University of Calgary CU181364

“Leve! Leve! Et puis…hurrah!”

We know this morning cry only because it was recorded in the journals of Father Albert Lacombe.[3] Few other sources from this time provide such colour. Surviving records from the 1850s are overwhelmingly from the Company’s point of view – concerned with reporting tasks the men (and rarely, the women) were engaged in, the quantity and type of furs traded, the amount of debt accrued by labourers, and – unfailingly – the weather.

Few accounts from non-Company sources survive: voyageurs, Métis country-wives, First Nations trappers. History from this period is like a York boat’s oar, pulled with a groan against the current if you want to explore any narrative not firmly in the HBC’s grip.

The story of the Braroes and their combination comes from none of the main parties, but two very different narrators.

(Image courtesy of Galt Museum & Archives P19754242000-2)

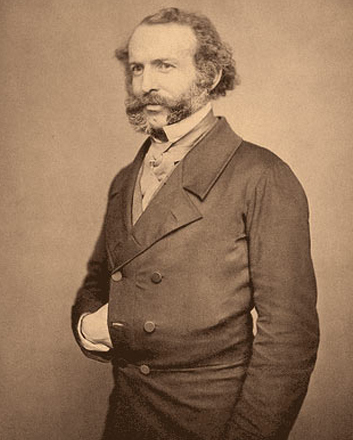

(Image courtesy of Royal Institution, via Wikimedia Commons)

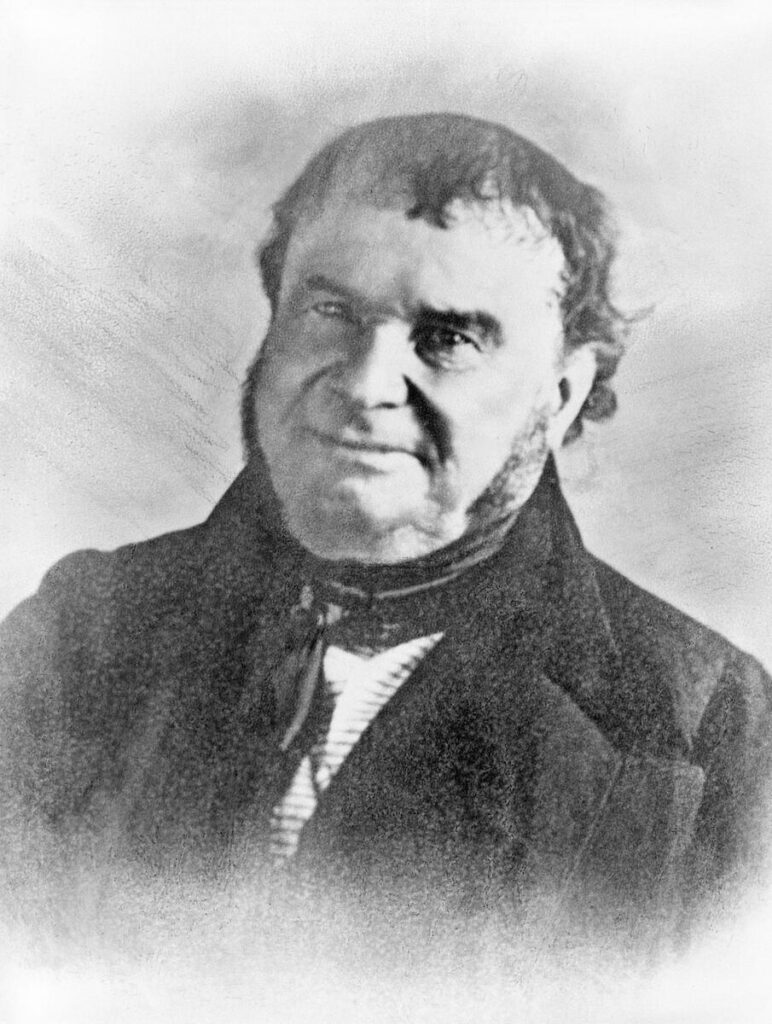

Two of the key players in the Combination that Gladstone and Rae identified were John Rowand and Cornelius Coghlan, both of Irish descent from Montreal, but with very different career paths.

If he ever wrote about his experiences, it has not survived – nor has a photograph.

“Leve! Leve! Et puis… hurrah!”

Usually when the Saskatchewan Brigade heard the morning cry, they had few choices but to comply. The non-natives among them were far from home. If a voyageur were in debt to the Company, which many were, their passage out of Rupert’s Land was thought by the Company to be…negotiable.

So when the Braroes began to near the Bay in 1853, a dilemma arose when labourer Cornelius Coghlan announced his resignation. He and his Edmonton-area boat crew refused to depart Norway House and continue on until he was granted leave to return home immediately, regardless of his contract. Moreover, John Rae’s account suggests that Coghlan threatened to shoot anyone who opposed him!

According to Gladstone’s account, the Company clerks and John Rowand himself refused to let Coghlan resign without paying his debts. The Company conspired to surprise him and clap him in irons for the impertinence. This set off the hornets’ nest.

The other Braroes backed Coghlan. They insisted that he be set free, and while they were at it, they decided to try to resolve some of their other grievances:

- More tea and sugar (A luxury always in high demand by the men.);

- Relief as it pertained to the Company horse policy; and, as it happened…

- …a cup of rum! (Rum was controlled strictly by the Company and given out to the men on holidays or as a reward for their hard work.[4])

According to Gladstone, this last demand was too much for Rowand. He was said to tear open his shirt to reveal his bare chest, crying “Strike!” in an amusing choice of words to modern ears. “You can kill me, but you can’t frighten me!”

Rowand’s cry was dramatic, but they weren’t going to kill him, they just weren’t going to work. As Gladstone put it, they wanted his rum, not his blood! Rowand had no alternative. The boat had to depart. The Company acquiesced to all of the requests.

What happened to Coghlan? John Rae’s account tells a not-very-triumphant end of the Combination for him. While the other Braroes left with their tea, sugar, and rum, Coghlan was clapped in irons and sent to the clerks for “trial.” Rae records that “no very serious punishment was inflicted.”

Courtesy of University of Calgary/Glenbow Archives CU186480.

“Leve! Leve! Et puis hurrah!”

The mutiny was not the first time, or the last time, that workers in Edmonton would make their demands known – and not the first time they would succeed. The Company seemed to be in retreat in many quarters.

One challenge was the growth of the Métis Nation. Also called Otipemisiwak – the people who owned themselves – they would not bend the knee to an entitled monopoly. About the same time as the Combination, they were making their views about the trade known in Red River.

Shortly before the Combination, HBC territory West of the Rocky Mountains had already been cut in half, leaving Oregon in the hands of American settlers. Much of the rest was being organized into official British colonies. Were the prairies far behind?

Employees of the Company, it should be said, did not make bad money. Historian Michael Payne has pointed out that equivalent salaries in Britain were not quite so generous.[5] Nonetheless, the Company treasured control above all.

And their control over land, trade, and employees was soon to change dramatically. By 1869 they finalized the sale of Rupert’s Land to the Dominion of Canada, changing the history of the North-west forever.

It was an entirely different kind of wake-up call, with its own consequences.

Sources:

Rae, John John Rae, Arctic Explorer: The Unfinished Autobiography. Edited by William Barr. (Edmonton: The University of Alberta Press, 2019).

Gladstone, W.S. “The Life of an Old Timer.” Rocky Mountain Echo, 4 Aug. 1903.

Further Reading:

Anderson, Nancy Marguerite, The York Factory Express, (Vancouver: Ronsdale Press, 2020.)

Burley, Edith I. Servants of the Honourable Company: Work, Discipline, and Conflict in the Hudson’s Bay Company, 1770-1879. (Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1997).

Hamilton, Scott. “Dynamics of Social Complexity in Early Nineteenth-Century British Fur-Trade Posts” International Journal of Historical Archaeology. Vol. 4, No. 3 (September 2000), pp. 217-273.

Payne, Michael, The Fur Trade in Canada: An Illustrated History, (Toronto: James Lorimer, 2004.)

Raffan James, Emperor of the North: Sir George Simpson and the Remarkable Story of the Hudson’s Bay Company, (Toronto: Harper Collins, 2007).

[1] Métis are the post-contact Indigenous people of the prairies with a distinct culture and languages. Orkadians are from the Orkney Islands north of Scotland, and a prime recruiting ground for the HBC. Before 1867, “Canadians” or “Canadiens” was generally used by the HBC to refer to French-speaking settlers from Lower Canada (later Canada East).

[2] The Company’s philosophy was expressed by Baptiste Bruce, a York Boat guide who introduced a new recruit to the idea: when a man pays for a thing (in this case a tump line, or leather carrying strap), he is careful. The employees didn’t always agree. As related in W.C King and Mary Weekes. “York Boat Brigade” The Beaver Outfit 271.December 1940. Pp 24-26.

[3] Hughes, Katherine, Father Lacombe, the black-robe voyageur, (New York, Moffat, Yard and company, 1911). Pdf. https://www.loc.gov/item/11030051/

[4] John Rae wrote that boat crews “received on their arrival at the Depot, what was called a “regale” consisting of paint of not very strong rum, which old custom made them consider as a sort of right.” Rae, John John Rae, Arctic Explorer: The Unfinished Autobiography. Edited by William Barr. (Edmonton: The University of Alberta Press, 2019). Pg 53. James Raffan’s Emperor of the North: Sir George Simpson and the Remarkable Story of the Hudson’s Bay Company (Toronto: Harper Collins, 2007) contains many references to this practice.

[5] Payne, Michael, The Fur Trade in Canada: An Illustrated History. (Toronto: James Lorimer, 2004), 65-66.