Every day I am reminded of the strength and resilience, and the endless love and kindness, of our mothers and grandmothers. I have fond memories of visiting my grandmother on the weekend, settling in to a cozy home that felt utterly safe. She was kind and selfless and patient, and as I approach adulthood and aging with open arms, I find myself wondering what her life must have been like on the prairies in the early 20th century.

My mind turns to life on Reserve. Rural life isn’t easy for anyone, but for Indigenous women especially, it was often dehumanizing and unjust. You were not afforded opportunities to improve your status, and the government was focused on disenfranchising you and ending your culture at the cost of your children and grandchildren. What could you do to grant yourself some agency?

In the late 1930s, the Department of Indian Affairs recognized that one of the best ways to ensure community compliance under settler-colonialism was through observation and overseeing activities and clubs. This led to the rise of Homemakers’ Clubs on reserves, including in Edmonton-area communities like Saddle Lake and Maskwacis (formerly Hobbema).[1] Women would work on their knitting, make dresses, learn home sciences like canning and pickling, and receive lectures relating to childcare and sanitation.[2] These women met regularly, often in a church basement or public building, and got to work.

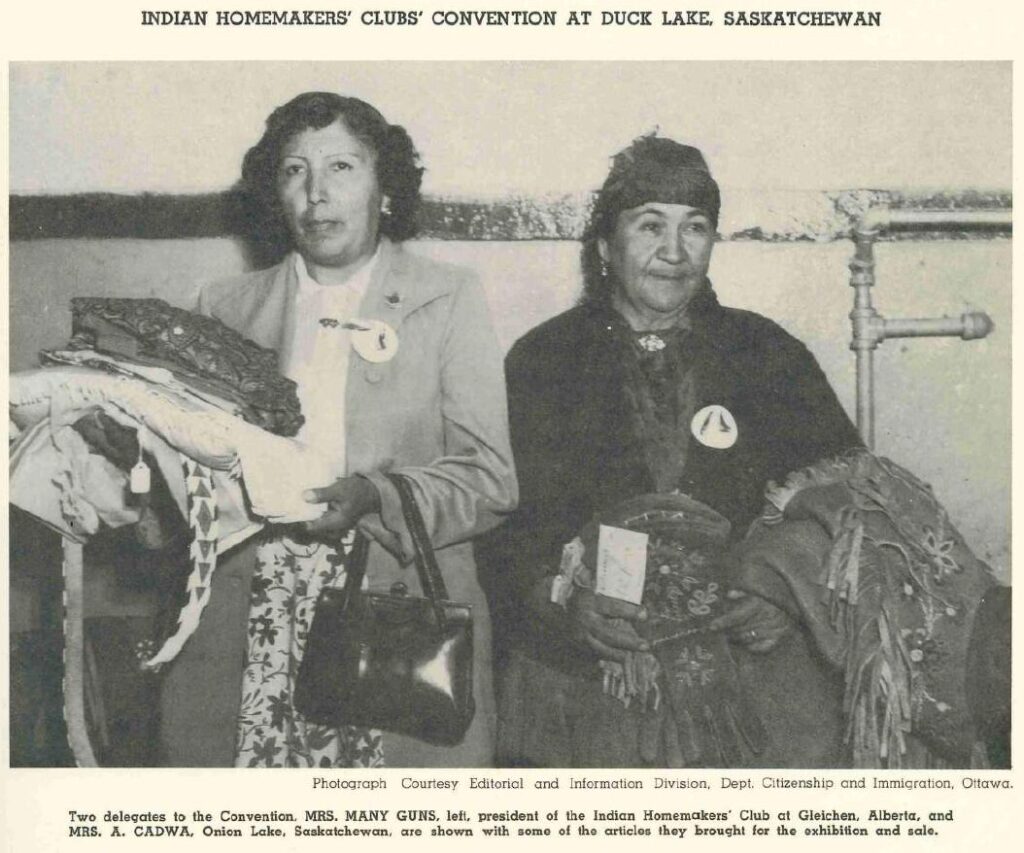

Josette Many Guns, president of the Gleichen Homemakers’ Club, alongside Mrs. A. Cadwa of the Onion Lake Homemakers’ Club showcasing their handicrafts at the Duck Lake Homemakers’ Convention in 1955. Photo courtesy of City of Edmonton Archives, from Charles Camsell Indian Hospital and Canadian Indians and Eskimos, Eighth Annual Pictorial Review, 1955.

Emma Minde was born in 1907 and raised in Saddle Lake, about 170 km northwest of Edmonton. In adulthood, she was a newcomer to Maskwacisihk when she married Joe Minde, a farmer, and joined his family. Moving from her home reserve to Maskwacis meant adapting to a new home, a new community, and new responsibilities. In a series of conversations with Frida Ahkenatew published in 1997, Emma described what life was like as a new wife in Maskwacis.

She recounts that women were always working, sewing clothing for themselves and their children, by hand or by sewing machine.[3] When their husbands were away, they’d drag back their own firewood and chop it to length for the fire.[4] She recounts that nearly all the women had a vegetable garden, where they grew potatoes and carrots.[5]

Laundry was done by hand with a washboard and tub, the water carried from a slough or well to boil over the fire.[6] Many women did beadwork, adorning jackets, moccasins, mittens and other clothing with beads to make some money.[7]

“They really made everything, the people did not buy very much, spending money to buy clothes for themselves,” Emma says.[8]

Despite the hard work, Emma fondly recalls the joy and kindness that persisted.

“People used to laugh so much long ago, telling one another stories, telling one another stories about everything, just as I am telling you. People would often talk about good things and also remind one another, what work they were doing at their homes.”[9]

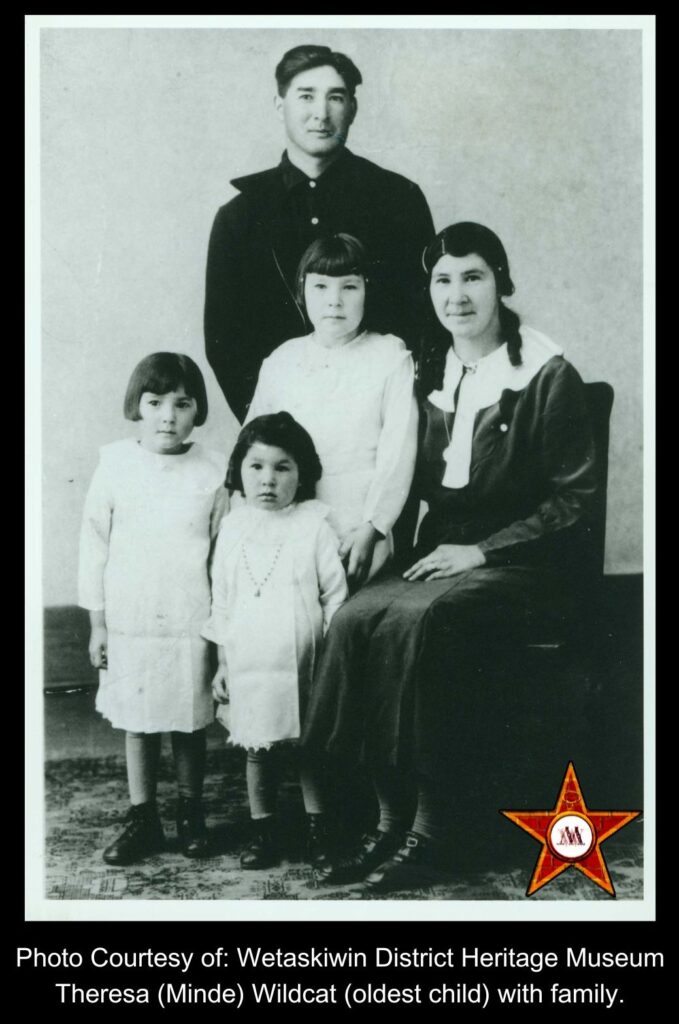

Emma Minde (right) with her husband Joseph Minde and children, including Theresa (Minde) Wildcat, c. 1930s.

This need for socialization is deeply human, and essential to women who were often relegated to the isolation of the home. They looked for opportunities to interact, to meet and chat and work on projects together. Many found them in the Homemakers’ Clubs and annual club conventions.

Emma Minde became president of the Hobbema (Maskwacis) Homemakers’ Club. She wrote about their work in Camsell Arrow, a publication by staff, patients, and others connected to Edmonton’s Charles Camsell Indian Hospital.[10]

The Hobbema club was founded in 1941, and had a membership of 30 women by 1955. Meetings were held once every two weeks, she explained, and discussed topics like education, “cooperation with missionaries and teachers at schools,” and more.

The club held a bingo in December of 1954, and used the proceeds to buy fifty gifts for “Hobbema Indian patients” at the Charles Camsell Indian Hospital “to bring them cheer and thrills for the Christmas season.”

Emma recalls that many hours were spent on charitable work between November 1954 and January 1955. She lists the sewing projects the group worked on over the winter, including making 36 sheets, 20 baby gowns, maternity belts, laundry bags, and diapers. These were made for the local Hobbema Indian Hospital.

Club members kept busy in the spring with sewing and mending clothes to be distributed by missionaries to other reservations, with clothing including summer and winter coats, children’s clothes and baby layettes.

As Emma recounts, the months of May and June were focused on beaded crafts and sewing for the upcoming Calgary Stampede and Edmonton Exhibition. Members created women’s and children’s dresses, scarves, beaded belts, embroidery, table cloths, pillow cases, men’s cowboy shirts, quilts, and “Indian design rugs.” She finished her letter by acknowledging that she was also president of the Ermineskin Residential School 4H club, where 28 girls were learning about clothing and etiquette.[11]

The many women of the Saddle Lake Homemaker’s Club. Photo likely from the 1950s, unknown photographer. Photo courtesy of Library and Archives Canada, R216, RG10, Box number: 3678, item 5383538.

At this point, you may notice a dilemma. While these groups were formed by Indigenous women, they had little agency in its direction or purpose.

Women wanting to organize a club needed to first seek the approval of the often male-dominated chief and council, who then had to submit a band council resolution to Indian Affairs.[12] Indian Affairs did not provide funding for these clubs – the costs were covered by the band accounts. Despite this, the popular narrative was that these women were being provided for by Indian Affairs because they could not provide for themselves.[13]

Homemakers’ Club Conventions were opportunities: a place where women were able to get to know each other, to share reports on their clubs, and to discuss shared issues and challenges in their communities.[14] They were aware that these issues were systemic, leading towards a greater understanding of the need for political organization.

The decline of Indian Homemakers’ Associations wasn’t universal across Canada. The 1960s saw the increasing organization of political groups led by Indigenous women, many of whom started their advocacy through homemakers’ clubs.[15]

The British Columbia Indian Homemakers’ Association was created in response to the lack of agency these women had in improving life on reserve and the reluctance of Indian Affairs to accept the changing mandates and purposes of the groups.[16] While the British Columbia homemakers’ clubs were adapting to include political advocacy, members in Alberta and Saskatchewan abandoned the clubs and instead created new Indigenous Women’s organizations.[17]

By 1969, there were only nine active Homemakers’ Clubs in Alberta, but there were twenty-six Indigenous women’s political organizations.[18] The simple conclusion is that these women had become fed up with Indian Affairs, had recognized the role they already played in their communities as leaders, and wanted a better life for themselves, their families, and their communities.

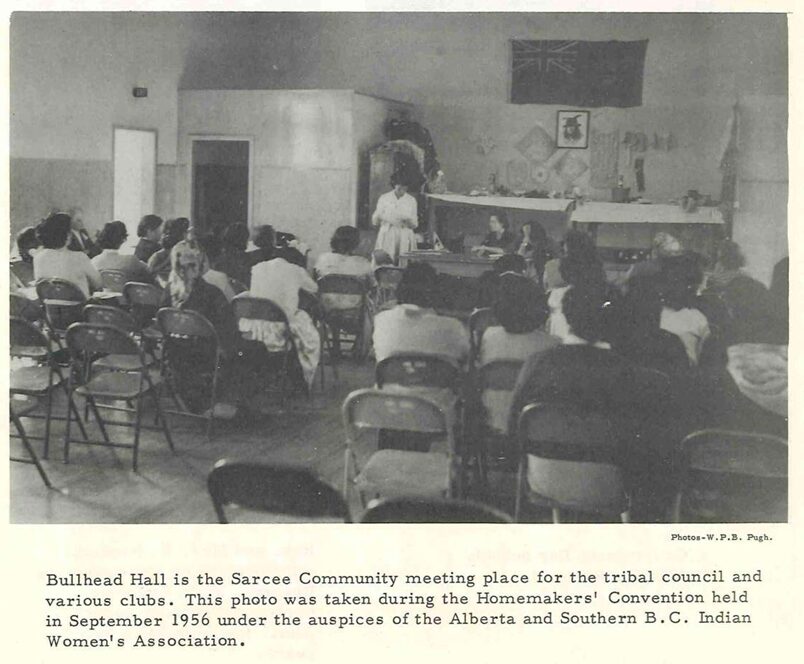

Bullhead Hall at Tsuu’tina (Sarcee), taken at the 1956 Indian Homemakers’ Convention for BC and Alberta. Photo courtesy of City of Edmonton Archives, from Charles Camsell Indian Hospital and Canadian Indians and Eskimos. Tenth Annual Pictorial Review. 1957.

In the modern era, we continue to face many of the same hardships as our grandmothers. Food insecurity, poverty, systemic discrimination. We can learn from their example by seeking out new skills and pastimes, volunteering with community organizations, and working together to seek a better future.

In this way, our grandmothers passed on their love and kindness to us. From their example, we can find ways to overcome our modern challenges.

Language note: The terms used throughout this article are not reflective of the diverse and distinct groups of Indigenous peoples across the prairies. Many terms used historically are discriminatory and outdated, including the term “Indian.” Many communities listed have since been renamed in the many years since this period in order to properly reflect the language and terms used by their inhabitants.

However, in the interest of historical accuracy as well as to honour the many proud indigenous people who resonate with the term, it is being included when directly mentioned by Indigenous and non-Indigenous people and organizations.

Maarsii!

References

Dempsey, Pauline. “Homemakers’ Club Convention For Alberta and BC,” The Camsell Arrow, Sept-Oct 1956. 49-50. City of Edmonton Archives. https://cityarchives.edmonton.ca/the-camsell-arrow-22.

Government of Canada. “CANADA DEPARTMENT OF CITIZENSHIP AND IMMIGRATION REPORT OF INDIAN AFFAIRS BRANCH FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDED MARCH 31, 1953.,” Library / Indian Affairs Annual Reports, 1864 to 1990, item number 33952, Library and Archives Canada. Accessed October 17, 2024. http://central.bac-lac.gc.ca/.redirect?app=indaffannrep&id=33952&lang=eng.

———. “CANADA DEPARTMENT OF MINES AND RESOURCES REPORT OF INDIAN AFFAIRS BRANCH FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDED MARCH 31, 1940.,” Library / Indian Affairs Annual Reports, 1864 to 1990, item number 33266, Library and Archives Canada. Accessed October 17, 2024. http://central.bac-lac.gc.ca/.redirect?app=indaffannrep&id=33266&lang=eng.

Minde, Emma. “Report of the Catholic Indian Women’s Homemakers Club of the Hobbema Indian Reserve,” The Camsell Arrow, May-June 1955. 8. City of Edmonton Archives. https://cityarchives.gov.edmonton.ab.ca/the-camsell-arrow-33.

Minde, Emma. Kwayask ê-kî-pê-kiskinowâpahtihicik = their example showed me the way: a Cree woman’s life shaped by two cultures, edited by H. C. Wolfart and Freda Ahenakew. University of Alberta Press, 1997. http://peel.library.ualberta.ca/bibliography/7449.html.

Nickel, Sarah A. “Making an Honest Effort: Indian Homemakers’ Clubs and Complex Settler Engagements.” in In Good Relation: History, Gender, and Kinship in Indigenous Feminisms, edited by Sarah Nickel and Amanda Fehr. University of Manitoba Press, 2020.

Nickel, Sarah A. “Sewing the Threads of Resilience: Twentieth Century Indian Homemakers’ Clubs in Western Canada.” in From Suffragette to Homesteader: Exploring British and Canadian Colonial Histories and Women’s Politics through Memoir, edited by Emily van der Meulen. Fernwood Publishing, 2018.

Scott, Duncan C. “Circulars Relating Education.” 243, April 17, 1926. Reference code PR1971.0220/9076, Provincial Archives of Alberta. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://searchprovincialarchives.alberta.ca/circulars-relating-education

Steinhauer, Margaret and Miss W.R. Broderick, “Indian Homemakers’ Club Convention,” The Camsell Arrow, July-Aug 1953. City of Edmonton Archives. https://cityarchives.gov.edmonton.ab.ca/the-camsell-arrow-22.

[1] Sarah Nickel, “Sewing the Threads of Resilience: Twentieth-Century Indian Homemakers’ Clubs in Western Canada,” in From Suffragette to Homesteader: Exploring British and Canadian Colonial Histories and Women’s Politics through Memoir, ed. Emily van der Meulen. (Fernwood Publishing, 2018), 166.

[2] “CANADA DEPARTMENT OF MINES AND RESOURCES REPORT OF INDIAN AFFAIRS BRANCH FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDED MARCH 31, 1940.,” Library / Indian Affairs Annual Reports, 1864 to 1990, item number 33266, Library and Archives Canada. Accessed October 17, 2024. http://central.bac-lac.gc.ca/.redirect?app=indaffannrep&id=33266&lang=eng.

[3] Emma Minde, Kwayask ê-kî-pê-kiskinowâpahtihicik = their example showed me the way: a Cree woman’s life shaped by two cultures, ed. H. C. Wolfart and Freda Ahenakew. (University of Alberta Press, 1997). 83.

[4] Minde, “Their Example,” 81.

[5] Minde, “Their Example,” 83.

[6] Minde, “Their Example,” 107.

[7] Minde, “Their Example,” 75.

[8] Minde, “Their Example,” 25.

[9] Minde, “Their Example,” 121.

[10] Emma Minde, “Report of the Catholic Indian Women’s Homemakers Club of the Hobbema Indian Reserve,” The Camsell Arrow, (May-June 1955): 8. https://cityarchives.gov.edmonton.ab.ca/the-camsell-arrow-33

[11] Minde, “Report”, 8.

[12] Sarah A. Nickel, “Sewing the Threads of Resilience: Twentieth Century Indian Homemakers’ Clubs in Western Canada.” in From Suffragette to Homesteader: Exploring British and Canadian Colonial Histories and Women’s Politics through Memoir, ed. Emily van der Meulen (Fernwood Publishing, 2018), 91.

[13] Nickel, “An Honest Effort,” 91.

[14] Nickel, “An Honest Effort,” 96.

[15] Nickel, “An Honest Effort,” 97.

[16] Nickel, “An Honest Effort,” 97.

[17] Nickel, “An Honest Effort,” 97.

[18] Nickel, “An Honest Effort,” 97.