Part 1: Sally Atkins: Black Land / Black Gold

As the train pulled into the station at North Portal, Saskatchewan, Sarah Atkins had no idea if she would be admitted into Canada. Her daughter and son-in-law, Naoma Atkins Hooks and Sam Hooks, had made it across the border and on to Edmonton. But that was before a backlash against African-American riled the city in 1911. Powerful groups such as the Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire (IODE) drummed up fear about a “black peril.” The IODE wrote: “we view with alarm the continuous and rapid influx of Negro settlers.”

The arrival of people like Sarah Atkins, in the IODE’s opinion, would “have the immediate effect of… discouraging white settlement in the vicinity of the Negro farms and will depreciate the value of all holdings within such areas.”

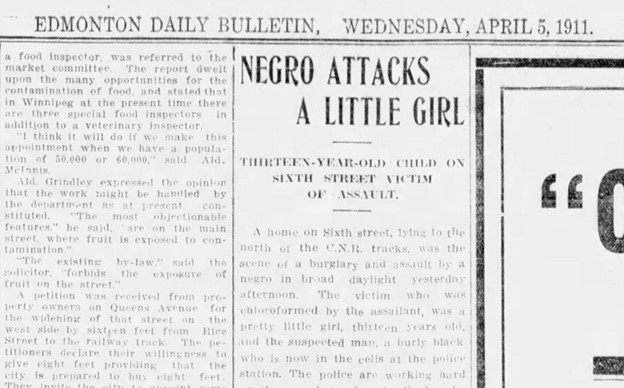

The fear-mongering had less of an effect on rural communities than it did in the city of Edmonton, where a full-blown racial panic was underway. Frank Oliver’s Edmonton Bulletin published a sensationalist account of an “attack” (code for rape) of a white girl by a black man on April 5, 1911.[1] According to the article, a 13-year-old girl was standing at the family stove when she saw a “burly black” with “his hands full of goods which he had collected in front of the house.”

The girl started to cry out, but the thief “seized her and in the struggle that followed her clothes were badly torn.” He muffled her cries with a chloroform-soaked handkerchief. She sank into unconsciousness and the man made off with the girl’s prized possession, a diamond ring. A positive identification of the suspect in a police lineup by the girl assured the Bulletin reporter that he had discovered “one of the worst outrages that has ever taken place in the city.”

The Edmonton Journal followed up on the story. A week later, it reported that the girl, Hazel Huff, had become distraught about losing the diamond ring. She feared a retribution from her parents and concocted a story about the attack. Seeing the hatred that the story unleashed, Huff recanted. “She did not dream it would cause the commotion it did,” the Journal reported on April 13. Huff “became frightened when the police arrested a negro, named J. F. Whitsue. Rather than see an innocent man in jeopardy for something he did not do, the girl confessed that she did it.”

This was the sort of story Sarah Atkins had seen before. In Oklahoma, these types of stories led to lynchings, and, a few years later, would be the proximate cause of the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921. Despite the escalation of anti-Black racism in Edmonton, Atkins was willing to take the risk.

Winter still hung in the air on March 25, 1913, with temperatures hovering around -20 as she stepped off a U.S. train for medical and financial inspections by border officials. Canadian immigration officials could send Atkins back for a minor illness or lack of money. Rigged medical exams and difficult financial requirements for people of African descent had slowed the entry of Black Americans to a trickle. Atkins had $120 in her pocket (around $3600 in today’s money and much more than the $25 federal requirement) and a daughter waiting for her in Edmonton. She was completely healthy.

Atkins and a few members of the Melton family (another Black Oklahoma family who would come to pioneer a famous downtown restaurant called Hattie’s Harlem Chicken Inn) caught a CPR train from North Portal to Edmonton. They had made it. Perhaps they breathed a sigh of relief, or braced themselves for another round of discrimination before setting out for the country. In the case of Sarah Atkins, Edmonton was supposed to be a temporary stopover while her daughter, Naoma, and son-in-law, Sam, waited for the land office to issue a title to their farm near Keystone (today, Breton), Alberta.

The city seemed to offer little in terms of security or opportunity for African-Americans. But no sooner did Sarah Atkins join her daughter and son-in-law on the farm in Keystone than a group of wealthy Oklahoman oilmen came looking for her in Edmonton. The men were accompanied by J.W. Robinson, a Pinkerton Detective Agent. They came bearing some incredible news about one of her children, a boy named Tommy Atkins.

The U.S. Consular Agent, a man named Hyatt Cox, conducted business out of the Hotel McDonald. A small group of businessmen, diplomats, and a private investigator tried to convince Atkins to go back to Oklahoma. Atkins, they said, had a chance to become one of the richest Black women in the nation. If she would just come back to Oklahoma and take part in a lawsuit against an oilman, she stood to receive millions. Most of her children had sold their land in Oklahoma to finance their move to Canada under duress. But her boy Tommy’s land was swindled from her. And it was located in the richest oil patch in the world. [2]

Atkins told her daughter in law that she hated the cold in Alberta. The cabin in Keystone was cramped, and Sam and Naoma had more children on the way. As she pondered this extraordinary offer, Atkins must have contemplated the path her life had taken, from slavery to freedom, from poverty to potential riches, from the oil patch of the present (Oklahoma) to the oil patch of the future (Alberta).

Up from Slavery to a Dream Deferred in Edmonton

Sarah Atkins was born in 1852 in Missouri as Sallie Porter1. Her enslaver was most likely a man named John S. Porter of Saline County, although it is hard to be certain since slave schedules in the United States only listed enslavers by name and not the enslaved. Saline County had been populated by settlers from the Old South hoping to transform Missouri into a plantation economy, but during Atkins’s childhood, that initiative had turned into a violent conflict, eventually leading to her emancipation in 1863.

In 1870, Sally (or Sallie) Atkins married an older widower named Richard Atkins, who many people in north-central Missouri referred to as “an Indian.” Richard had a light complexion, and was said to have been brought to Missouri from Indian Territory (what is now Oklahoma) as a young child. Richard worked odd jobs for former enslavers in Missouri in the 1870s, soon realizing that Reconstruction would result in a different form of oppression.

The reality of Jim Crow included an prohibition on interracial marriages. The part-Native American Richard and the African-American Sarah decided to reconsider Richard’s kinship networks to the Muscogee Nation in Indian Territory. Richard’s mother told her son that his father was a tustenuggee (warrior) who had become a Captain of the Lighthorse in the Muscogee Nation. This man’s name was Thomas Atkins and he was, in the words of the Muscogee Chief, Pleasant Porter, “a bit of a wild fellow.”

Richard left Sarah and their children in Missouri, lighting out for the town of Coweta or Wagoner in the Muscogee Nation (just southeast of present-day Tulsa, Oklahoma). The Muscogee National Council was wary (then, as now) of people from the States claiming blood ties to the Tribe. The Muscogee (also known as the “Creeks”) had been removed from their traditional homelands in Georgia and Alabama on a trail they called “The Road of Misery.”

After considerable debate, Richard was enrolled in Cheyaha Town, populated by “Muscogee by blood.” Richard voted in every Muscogee election and became a well-known figure around the town of Wagoner. Richard called for Sarah and their children to come join him. Indian Territory seemed like a haven of racial diversity and tolerance at first. Black Creeks (“estelvste”) served in the Nation’s Supreme Court, the House of Kings, and the House of Warriors. But the mixed-race society based on Native American customs was upended by the advent of Oklahoma statehood, which sought to impose white supremacy in every aspect of society–from the ballot box to the train car.

This pattern would repeat itself in Canada only a decade later. Freedpeople (the name for formerly enslaved people of the Five Tribes) carved out a unique cultural identity in Oklahoma. They built arbors and homes like the Muscogee. Most spoke Mvskoke as a first language; they wore moccasins, beads, and textiles common among other Muscogee. Freedpeople belonged to ancient tribal towns and sung hymns in Mvskoke; they blended Indigenous ceremonies around the corn busk with elements of Christianity. The mix of African, Indigenous, and white patterns of culture caught visitors from Canada by surprise.

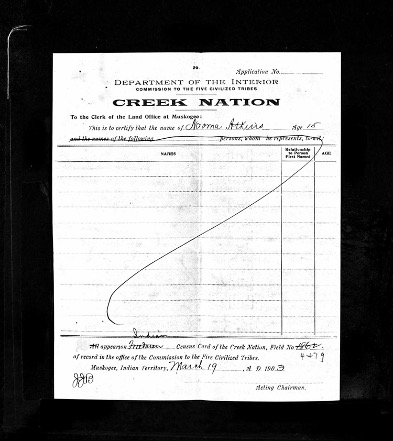

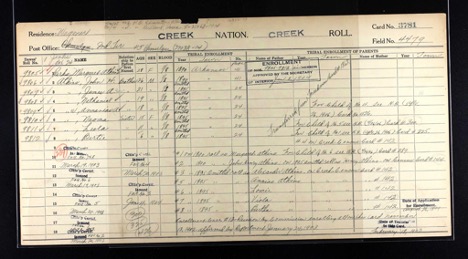

Naoma Atkins, who would later retire in Edmonton, selected an allotment next to her brothers and sister in Tiger Township, near Okmulgee in 1903. An inkling of the confusion to come regarding the Atkins family is apparent on Naoma Atkins’ enrollment card in the Muscogee (Creek) Nation. Where it is written “Freedman census card,” someone crossed out “Freedman” and wrote “Indian.” Other such confusions dot the paperwork, as colonialist administrators guessed at degrees of Indigenous and African blood in a mixed-race society.

At the same time, Black Oklahoma newspapers were advertising Canada as a country which promised land “absolutely free to every settler.” The land was perfect for wheat, barley, and oats. And, thankfully, there was no cotton. For people like Sally Atkins, the mere sight of cotton fields triggered a feeling of dread. Atkins’ son-in-law, Willis Day, would speak for many in the family when he told a writer, “I never want to see another field of cotton.”[3]

One of Richard and Sally’s twelve children fell ill with a mysterious liver disease after a long day of picking cotton. This boy, Thomas, was the only child not to survive into middle age. The other eleven children remember him well. His older brother, Ananias, sat by his bedside as Thomas grew sicker. A week later, the boy was dead. As the dream of Black and Indigenous homeland in Oklahoma faded, many Blacks went to Canada, while others followed a leader named Chief Sam to a colony on the west coast of Africa.

Richard Atkins died in 1898, leaving Sarah Atkins alone to fight for her rights for her children to be recognized as Muscogee citizens. The scrawling notations on the Atkins’ family Creek Nation Census Roll stands as a testament to the dilemma, their migration to Canada only adding to confusion. This roll notes the denial of tribal citizenship, the successful appeal to that denial, and then, in pencil, near the entry for Post Office, “Maidstone, Saskatchewan, Canada,” referring to the home of Nancy Atkins Taborn, another of Sally’s children that opted to leave Oklahoma.

Put together, the Atkins family still owned a large swath of fertile land, some of it perfect for farming, and some of it rich in mineral wealth. This led to a brief period of prosperity that rested on a tragic paradox, as noted by the Freedperson descendant Dr. Alaina Roberts in her book, I’ve Been Here All the While: Black Freedom on Native Land. Roberts writes that the allotment of tribal land allowed a measure of Black prosperity, but this was “part of the broader theft of Indian land that also led to the loss of much Native sovereignty, culture, and language” in Oklahoma.

Allotment, in other words, might have created unprecedented wealth for some Freedpeople, but it was only made possible by the dismantling of tribal governance and an Indigenous system of land tenure that emphasized the commons.

The second decade of the 20th century brought an explosive transformation to Oklahoma, as the heart of the petroleum industry, the geographical centre of the vast Mid-Continent Oilfield. Sally Atkins, shortly before immigrating, watched as some of her friends and neighbours came into fortunes that sounded like fantasies. Weighing against her decision to immigrate was the story of another Black woman from around Okmulgee, Sarah Rector. By 1913, Rector had become a celebrity, the “Richest Black Girl in America.” Luther Manuel, another boy Atkins had known, was pulling in around $10,000 a month (around $300,000 in today’s dollars)[4].

Considering the possibilities of immense wealth in Oklahoma, why did Sally Atkins give up everything to help her children build a log cabin covered in tar paper in the wilds of Alberta? For every Sarah Rector or Luther Manuel, it seems, there were dozens of nightmarish stories involving Freedpeople and their land. One set of Freedman siblings were dynamited in their sleep when their mother refused to sell their property to oilmen. Lynchings were so common in Creek and Okfuskee Counties that newspapers often ran stories about them in columns below stories about the peach harvest.

The first wave of Black migrants to Edmonton detected a mixture of curiosity and disdain from the white elites. They weren’t entirely welcome, but no one was driving them out at gunpoint either. This started to change, as the Edmonton Board of Trade, Frank Oliver, and Imperial Order of the Daughter of Empire, launched a campaign to bar Black immigrants to Canada. The Hazel Huff fake news story set the entire city on edge.

And yet, African-Americans, many of Native American descent, started to reshape the city. Sally Atkins’ granddaughter by marriage, Gwen Hooks, wrote about this era in a book called The Keystone Legacy: Recollections of a Black Settler.

At first, the Black immigrants had to pitch a camp in the city near Immigration Hall. Some of these new arrivals had suffered through slavery. There was little appetite to settle in Edmonton itself. Gwen Hooks wrote:

Most of the black families lived around 97th and 101st streets. Edmonton was a rough male-dominated–a city where many women fell into prostitution, some out of desperation, others because that profession was one of the few open to women that offered financial opportunities. Young women, new to Edmonton, were particularly vulnerable. Women’s groups did what they could to protect girls arriving in Edmonton. Through the YWCA, booths were set up at the train station to meet incoming women new to Edmonton and escort them to decent quarters in which they could spend the first few nights until they could establish themselves. The YWCA had renovated an old barn behind their building to serve as a special dormitory for young women to stay temporarily.

It is a lamentable fact that much of this history has been erased or neglected. We know from oral histories (and Hooks’ book) that many Black families lived in McCauley, setting up businesses, a church, and attending school. Yet this history is entirely missing from Edmonton Historical Board’s history of the neighbourhood.

Ready for the Country

Even as Black migrants faced increasing hostility in Edmonton, they found the peace and freedom they sought in the countryside. And this brings us to another contradiction impossible to avoid in consideration of the extended Atkins family. They were African-Native American people unwittingly recruited into a settler colonial regime in Canada that was actively seizing traditional lands of Indigenous peoples and undermining their nations’ sovereignty. This led to some interesting interactions between Indigenous people around Keystone and the Atkins women. As Mark Hooks said, “Being part Creek, [my mother-in-law, Naoma Hooks] spoke Cree fluently. When natives came by the homestead, she often conversed with them in their own language.”[5] Whatever kinship that might have been felt between the Muscogee Atkins and Cree hunters around the homestead would be cast in a totally different light when it came to the official Canadian policy. “Indians could hunt out of season,” Hooks wrote. “[I]n the States, we were considered Indians and the Canadian government representatives themselves referred to us as Indians on occasion.”[6]

It is not until the Atkins’ story is reread within the context of anti-Indigeneity within Canada, however, that all of this makes sense. None other than Frank Oliver himself sounded an alarm about the element of Indigenous ancestry within the Black population. One of Oliver’s agents wrote back to say that many of the migrants, “were mostly half breed lndian negroes.”[7]

Naoma Atkins, Nancy Atkins Taborn, and others who were enrolled in tribes in Oklahoma quickly learned that, in Canada at least, they were settlers. That status afforded them certain rights and privileges denied to Indigenous people under the Indian Act. It prevented their children from being shipped off to residential schools. But it also meant that an important line of cultural heritage, linking rural Alberta to Oklahoma, and then all the way back to the southeastern portion of North America was severed. The culture of the estelvste (African Creek), heavily influenced by Mvskoke foodways, spirituality, and music survived the Road of Misery from the Southeast to Oklahoma, but it did not survive (at least in any public form) the climate of anti-Indigeneity in Canada.

Part 2: Turning Back on the Road of Misery: Sally Atkins from Edmonton to Oklahoma

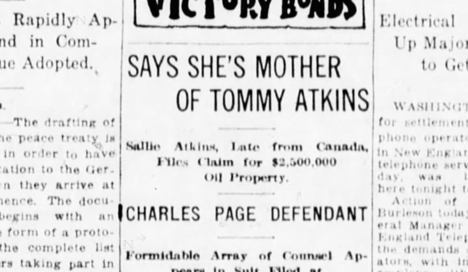

As Sally Atkins was settling into a new life in a cab in Keystone, news about a certain Tommy Atkins graced the headlines of newspapers in the southwestern United States. “The Story of Tommy Atkins to Be Told in Supreme Court — Did He Really Exist? — Millions Involved” went one such headline.

At first glance, it seemed like a coincidence that Sally’s dead son had the same name as a mixed-blood Muscogee boy sitting on millions of dollars worth of oil. The two women who claimed to be Tommy’s mother, Nancy and Minnie Atkins, were from a Euchee tribal town far from Sally Atkins’ family. They were part of the same Nation–Muscogee–but from different tribal towns with different kinship networks. While Sally was of African descent, Minnie and Nancy traced their ancestry to a mix of white and Indigenous people. As oilmen battled each other to control the lease to his oil-rich land, Sally Atkins worked with her daughter Naoma to pick berries, greens, and wild mushrooms on their quarter-section near Keystone.

Then came news by way of the U.S. Consular Agent in Edmonton, Hyatt Cox. A pair of oilmen from the Gypsy Oil Company in Oklahoma canvassed western Canada, looking for Sally. They had gone from British Columbia to Saskatchewan, and were now in Edmonton. The men from the Gypsy Oil Co. were not the only people looking for Atkins. Pinkerton agents were also searching for her, employed by independent oil producers in Muskogee. Cox ran his business out of the Hotel Macdonald in Edmonton and made arrangements to bring Atkins to the city, where she would meet with several prominent Edmontonians. On June 9, 1917, Atkins signed a mineral lease to a little known man named L. J. Rosier. This lease was recorded in Edmonton, and then the men escorted Sally Atkins back to Oklahoma. As was common these days, men from the Pinkerton Agency provided the muscle, intimidation, and threats to enforce the schemes of the wealthy.

Sally’s children had dispersed around North America. Three of the twelve had come to Canada, some remained in Oklahoma, and others went to California. By 1929, however, they had all reunited around one lawsuit, initiated by Oklahoma attorney Charles West. The Atkins family, led by Sally, sued the millionaire oilman and philanthropist Charles Page for illegally appropriating Thomas Aktins’s land and mineral rights in Creek County, Oklahoma. The fair value of the property and mineral rights was just over $4 million. If Sally Atkins and her children prevailed, the man known as “Oklahoma’s Rockefeller” would owe them what would amount to around $70 million in today’s money.

Like Rockefeller, Page maintained a vast charitable network that burnished his image. His chief nonprofit institution was the Sand Springs Colony for Widows and Orphans, a nationally-respected home for people who had few options in a society without a real social safety net. Unlike Rockefeller, Page was reported to have donated all of his profits to his philanthropy, even making the “Sand Springs Home” as the inheritor of his vast fortune.

But was Page an absolutely selfless businessman devoted to the less fortunate, or was there more to the story? It was a question that the Tulsa Daily World investigated as the Atkins case unfolded. But the story was not simply a sensationalist news item, by 1930, it was the target of an FBI investigation signed off by J. Edgar Hoover.

Page’s right hand man, a former Indian Agent named Frank B. Long, was furious at Sally Atkins and her children. Long brought back the old accusation made by the other Richard Atkins, that the family was no Muscogee at all. “According to my files,” Long wrote, “this Richard Atkins came into the Indian Territory in the early 80’s from Missouri where he had been known as Richard or “Dick” Havens. He made some sort of a connection with the Atkins family down there and claimed to be an illegitimate son of old Thomas Atkins.”

Long thought Atkins’ case was far-fetched. “I’m willing to bet we know more about their client than they do,” he wrote to another attorney, C.B. Stuart. Page, Long, and company had already won a contentious lawsuit against the Muscogee Nation and the U.S. Attorney’s Office in 1915. The tribe–along with the federal government–alleged that Charles Page’s Tommy Atkins was a complete fiction, cooked up by a gullible Muscogee woman and a vast network of paid witnesses, who swore they saw Minnie Atkins with a baby named Tommy near Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, in the 1880s.

This latest lawsuit, by Sally Atkins, Black woman who had returned from Canada, backed by some small-town lawyers, felt like an easy win for Long and Page. Their correspondence brims with a mix of disdain for their adversaries and over-confidence in their legal strategy. They underestimated their rivals.

No one could question whether Sally had a boy named Thomas, but Page’s lawyers (who included an ex-Governor of the state), tried to argue that he wasn’t truly Native American. Sally Atkins’ lawyer brought forth the wife of a Muscogee judge, who remembered Minnie Atkins asking for annuity payments for her children. Minnie, presented with the opportunity to claim extra money for a son named Tommy, said she had no son by that name. Sally, on the other hand, had a mountain of evidence showing that, one, she had a son named Tommy, and two, that the Dawes Commission had allotted him land out in the western portion of Creek County, where many Freedpeople and rebels against the U.S. government received their lands. The claim was compelling to Judge Lucien B. Wright of Creek County. He put a $2 million bond on Charles Page’s businesses, and demanded a full accounting of all the oil wells, tanks, train tracks, and other industry built on the Tommy Atkins allotment so that it could be properly transferred to Tommy’s true heir, his mother, Sally Atkins, formerly of Edmonton, Alta.

Page’s lawyers posited that racial mixtures did not exist in Thomas Atkins’s tribal town. “Euchee town was different from the other towns in the Creek Nation,” Frank B. Long wrote. With one or two exceptions there were no kinky haired families in Euchee town; that Euchee town was almost wholly free from negro taints.”

Ideas about racial purity were recent constructs in Oklahoma, and this one was contradicted by the tribe’s own records. Sally Atkins was awarded close to $4 million in 1921 by Judge Lucien B. Wright in a Creek County courtroom. This former Canadian migrant, fleeing persecution in Oklahoma, had returned and showed one of the state’s most powerful people to be engaged in a massive fraud. Indeed, later cases showed that the Sand Springs Home was operating as a for-profit corporation in order to secure Charles Page a tax break.

Almost as soon as she shocked the world with her victory over Charles Page, however, a bribery scandal threatened to destroy Judge Wright’s career. Page, furious at the ruling, sought to destroy the judge who brought it about. Page’s newspapers printed stories of Judge Wright hanging out on his porch, sipping bootlegged whiskey with grifters who bribed him to award Native American lands to shady characters in the oil industry. One Oklahoma newspaper went so far as to say Judge Wright planned an assassination of Charles Page. The judge was later acquitted on all charges, but the accusations led to a retrial, first in the Oklahoma Supreme Court, and later in the United States Supreme Court, of Sally Akins’ case.

A year after the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, Sally Atkins returned to a courtroom one more time, to testify about her missing son, Thomas Atkins. Nothing she could say could overcome the original findings of the Dawes Commission in 1902. The boy, according to this quasi-judicial body, was the son of a nameless “white man,” and a Muscogee citizen, now deceased, named Minnie Atkins. Minnie, before her mysterious death, deeded Tommy’s land to Charles Page’s Sand Springs Home, which became the owner of the land and its vast riches.

The Sand Springs Museum today features a permanent exhibit on the philanthropist and oilman Charles Page. A small panel features a photo of Minnie Atkins, an Indian Boarding School survivor, shortly before her death in 1919. Nothing in the museum or the vast land held by the Sand Springs Home attests to the alternative, plausible history of this place, a history that winds from Indian Territory to Edmonton, to a farm near Leduc, and then all the back to the erstwhile Oil Capital of the World, Tulsa, Oklahoma. Naoma Atkins Hooks, having spent most of her life on a farm in Keystone, retired to an Edmonton neighbourhood just north of Commonwealth Stadium. She lived in a tidy, one-story brick cottage, just down the street from Hatti Melton, the proprietor of Hatti’s Harlem Chicken Inn from the 1940s until the 1960s. Melton, like Atkins, had many opportunities to go back to Oklahoma and rekindle the dream of a Black homeland, but stayed put in Edmonton, despite a climate of racism in the city. Naoma Atkins Hooks died in 1965, and was buried at Beechmount Cemetery in Edmonton.

Footnotes

[1] https://citymuseumedmonton.ca/2021/05/24/sustained-opposition-to-black-immigration/

[2] During World War I, around 20% of all North American petroleum originated in this narrow stretch of land known as the Cushing-Drumright Oilfield in eastern Oklahoma, an area smaller than the city of Edmonton.

[3] Gwen Hooks, p. 8

[4] For a fuller context of the Freedpeople, please see this ECAMP series.

[5] Hooks is probably mistaking “Cree” for “Creek” here. “Creek” is a name Europeans gave to a loose confederation of southeastern Indigenous peoples, now referred to by their traditional name, Mvskoke. Mvskoke and Nehiyaw are unrelated linguistically, but may have several words in common.

[6] p.55

[7] Mundende, Darlington Chongo. “African immigration to Canada since World War II.” (1982).

Please note: as of February, 2024, Dr. Russell Cobb’s book The Ghosts of Crook County: An Oil Fortune, A Phantom Child, and the Fight for Indigenous Land, which tells the full Tommy Atkins story, is now available for pre-sale.

- Atkins told the Dawes Commission that her “right name” was Sarah, but everyone called her Sallie or Sally. ↩︎