While Alberta is often understood as a prairie province, Edmonton is nestled within a geographical zone known as aspen parkland: an ecoregion that exists as a meeting place between northern boreal forests and southern grassland. The hybrid nature of the Edmonton region contributes to its patchwork of natural features, including forested valleys and ravines; wetlands and riparian areas; swampy peatlands; and prairie grassland and shrubland[1].

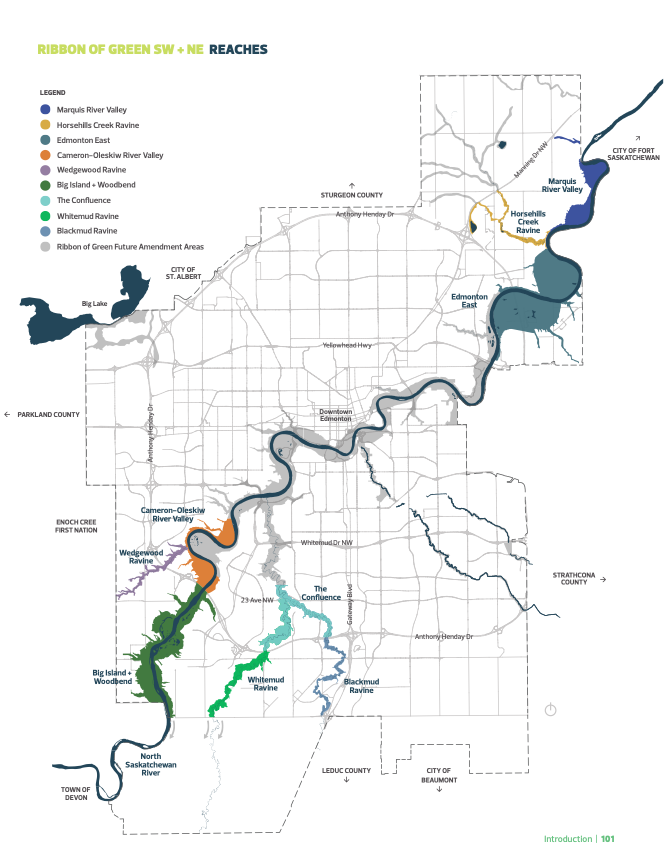

Amidst this patchwork, the 2008 Edmonton Biodiversity Report identifies the North Saskatchewan River Valley and Ravines System, our “Ribbon of Green,” as the backbone of the city’s ecological network. Being the largest, contiguous stretch of municipal parkland in Canada, the predominant position the River Valley takes in discussions of conservation is well-deserved. As Edmonton’s most defining feature, the River Valley is a vital wildlife corridor that links our city to other communities and strengthens our bond with our animal and plant neighbours. An undeniable presence to all those who live in proximity to it, the Valley acts both as a boundary and an extension to city life.

However, the centrality of the River Valley system, in both a physical and conceptual sense, has historically meant that the other natural features in our aspen parkland landscape have more easily fallen to the bulldozer and a collective drive for urban growth.

Nature and society are in a constant cycle of shaping and affecting one another. In the same way old buildings give us a material connection to the past, holding the memories of persons and events that took place, nature also bears the marks of our interactions with it. Without diminishing the importance of the River Valley, it is imperative that we protect and defend other pockets of natural space that equally contribute to our landscape. Despite not being quite as grand as the Valley, the tablelands also capture who we are as a city and how we got here.

A general disregard for the lands above the river has cost us the disturbance, if not the complete destruction, of many natural sites and the stories they held. Some of these lost sites contained big foundational stories, such as Kinokamau Lake: a former Metis settlement in Edmonton’s north-west whose history goes back to the time of the original fort and whose inhabitants were displaced towards the end of the 19th century. Kinokamau Lake has since been almost entirely drained and the area has been developed into an industrial quarter.

Other lost sites, while smaller in scale and more ambiguous in their cultural ties, have yet to be given a chance to tell their stories.

For this reason, I would like to bring your attention to one natural space whose history has been obscured: The Winterburn Woodland.

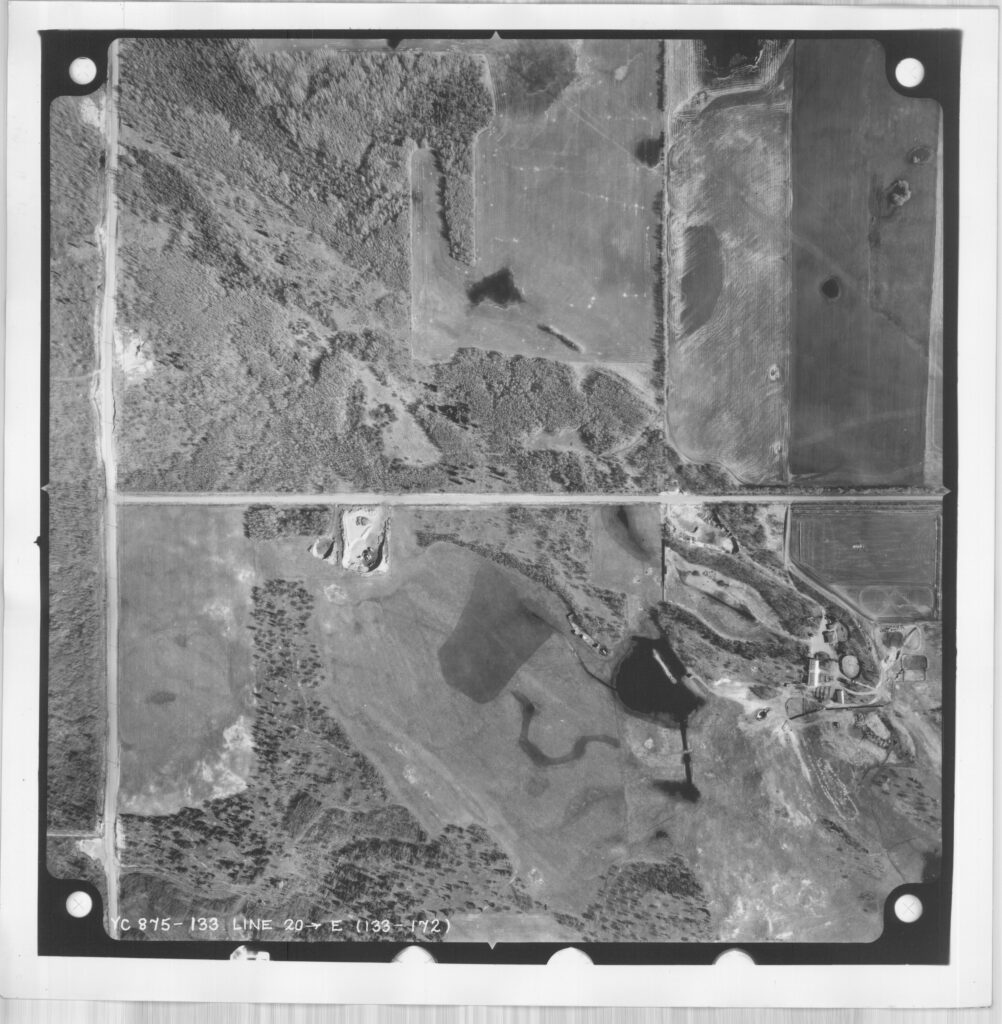

The Winterburn Woodland was a 46-hectare tableland forest that populated the lands south of Whitemud Drive, along 215 Street (Winterburn Road). The origin of the name “Winterburn” is ambiguous: one possible explanation is an old English term meaning “a stream dry except in winter”[2]; however, a more local explanation could refer to the burning of the muskeg in the area. Muskeg and other peatlands are carbon-rich environments, making them highly susceptible to fire when dry. They are known to smoulder for months, burning furtively throughout the winter under layers of ice and snow.

Today, only 8 hectares of the original Winterburn Woodland remain within Edmonton’s boundaries, as part of The Hamptons neighbourhood. Prior to its partial destruction, a 1993 study conducted by Geowest Environmental Consultants identified the area as one of 38 significant environmentally sensitive areas in the city, and one of 4 areas of regional significance, stating:

“The diversity of vegetation communities found within the Winterburn Woodlot is unparalleled within the [city’s] tableland area”[3].

Before development, the area was characterized by unique patches of vegetation, including upland layers of low-bush cranberry, raspberry, rose, and beaked hazelnut; and lowland wetland areas consisting of black spruce, larch, paper birch, and “extensive occurrences”[4] of lady fern and oak fern.

In addition to its plant richness, the Winterburn Woodland provided critical habitat for white-tailed deer and 33 avian species, including a pair of Cooper’s hawks, which were considered a vulnerable species in the 1990s, and one of the largest populations of western wood-pewee in the city. Precisely because of the area’s high species diversity, and the sensitivity of the local wetland hydrology, Geowest advised against further disturbances to the woodland, which, at the time of their report, had already been significantly degraded:

Significant portions of the site have previously been cleared for sand and gravel extractions and for rights-of-way. Today, portions of this cleared area [are] used as a dumping area for garbage… It is imperative that the ecological integrity of the site is maintained and enhanced because the site offers such a unique set of environmental conditions for education and research.

(Geowest, 1993, p.140)

On May 25, 1998, the City of Edmonton approved The Hamptons Neighbourhood Structure Plan and, consequently, the plan to bulldoze the majority of the Winterburn Woodland. At the time, the corporate landowners, Carma Developers Ltd. and The Grange Property Corp., claimed to have conducted their own geotechnical study of the site and recommended preserving only 4.5 hectares of the northwest portion of the woodland, excluding the wetlands entirely. Their argument was that preserving the wetlands would not be economically viable or sustainable, and the wetlands would not integrate well with the proposed urban development. Speaking in opposition to the woodland’s destruction, Patsy Cotterill, a botanist and member of the Edmonton Natural History Club, appeared before Council to advocate for the preservation of a larger portion of the natural area. Cotteril asked that more studies be done on the wetlands to retain it for further educational and recreational use. In the end, the corporate landowners were successful in arguing for a smaller natural reserve.

After the public hearing in which the majority of the Winterburn Woodland was given over to private development, Cotterill was quoted in the May 29, 1998 issue of the Edmonton Examiner: “That woodland has existed something in the order of 2,000 years.” Whether or not this was the exact age of the woodland, Cotteril’s statement is a sharp reminder of the permanence of losing natural areas and the knowledge they hold. After all, individual trees alone may live for hundreds of years, and generations of trees may live within the same site for more than that, having been interacted with and tended to by generations of people in turn. Unfortunately, once cut or dug up, history cannot be regrown.

While the Winterburn Woodland has been stripped of its original size and richness, the fragment that remains may still have something to tell us. It’s worth noting that the Winterburn Woodland’s potential Indigenous context did not seem to factor into the debate over its development apart from a general awareness of the fact that it extended into Enoch Cree Nation.

When it comes to discussions of conservation in dominant Canadian and American institutions, an assumption that is often made is that the nature we want to protect is incidental wilderness, pure and untouched by humans. Or at least only partially disturbed wilderness that would be better off without further intervention. Something that is often missed in these arguments is that there are, in fact, few natural landscapes that have been completely unmarked by human passage.

Untangling the contentious history of the USA’s national parks, and this myth of wilderness, Ojibwe writer David Treuer states:

“The North American continent has not been a wilderness for at least 15,000 years: Many of the landscapes that became national parks had been shaped by Native peoples for millennia… The idea of a virgin American wilderness—an Eden untouched by humans and devoid of sin—is an illusion.” [5]

The truth is human touch is not inherently anathema to a thriving landscape. As Treuer points out, the reason European colonists perceived North America as an overflowing garden and later sought to isolate and preserve its most abundant areas in the form of national parks was directly due to Indigenous peoples’ land use and stewardship practices.

However, the expansionist growth of North American cities, rooted in colonial systems and structures, has historically encouraged a single type of relationship between humans and the land: one that is extractive and selfish as opposed to reciprocal and restorative.

If we set aside for a moment the fact that all of Edmonton is built upon Indigenous land, knowing that the area of West Edmonton that the Winterburn Woodland grew in was all originally part of Enoch Cree Nation, the “unparalleled” richness of this former forest is a signal that this land was most likely cared for and cultivated in an intentional way to develop the unique vegetative patchwork it once contained. Although only a piece of it remains of what it once was, I believe the Winterburn Woodland is still worth protecting and remembering.

Footnotes

[1] Edmonton Biodiversity Report, 2008, p. 10

[2] City of Edmonton, 2004, p. 347

[3] Geowest, 1993, p. 137

[4] Geowest, 1993, p. 137

[5] Treuer, 2021

List of Sources

City of Edmonton. (2004). Naming Edmonton: From Ada to Zoie. University of Alberta Press.

City of Edmonton. (2008). Biodiversity report.

Geowest Environmental Consulting Ltd. (1993). Inventory of environmentally sensitive and significant natural areas: City of Edmonton.

Loyie, F. (1998). West-end woodland will fall to bulldozer’s blade. Edmonton Journal, May 26 1998.

Kohut, K. (1998). Woodland faces bulldozer. Edmonton Examiner, May 29, 1998.

Treuer, D. (2021). Return the national parks to the tribes. The Atlantic, May 2021. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2021/05/return-the-national-parks-to-the-tribes/618395/. Correspondence, Patsy Cotteril, November 11, 2021, Edmonton, AB