Would you be surprised if I told you that Edmonton’s schools were a more prominent contributor to Edmonton’s 1918 influenza response than the city’s hospitals?

Wait, you might say- weren’t schools closed during the 1918 epidemic? Yes, they were.

And so were churches, theatres, and cinemas- and anywhere else large numbers of people might congregate. Since classes were cancelled, Edmonton’s school buildings were available for other uses and a handful were transformed into operational headquarters for volunteer organizations which looked after sick and suffering Edmontonians.

“Epidemic Influenza,” or “Spanish flu” as it is sometimes erroneously called, arrived in Edmonton in mid-October 1918 and raged through the city for weeks before slowing down (but not ending) in December 1918.[1] During those two-and-a-half-months more than 10% of Edmonton’s population reported getting sick. The city’s Medical Health Officer estimated that there were hundreds more unreported cases.[2]

As people became sick, households across the city fell into desperate situations with no one to do the daily chores necessary for survival: caring for small children, making fires to keep the house warm, chopping wood or shovelling coal, cooking, washing dishes, doing laundry, running errands, and of course, nursing any members of the household who were sick.

People of any age could contract this highly contagious influenza variant.

This Edmonton Bulletin description of the Calder railway community illustrates how incapacitated many neighbourhoods were:

“No district in the city was harder hit by the influenza epidemic than Calder, and in no district have more energetic, whole-hearted and self-sacrificing efforts been made to combat the disease….It is a region of small homes and large families.

When it is stated that at the peak of the epidemic no less than ninety-eight families were quarantined for influenza and that in many cases every person in the household, numbering from six to eight, was down with the disease, the magnitude of the problem to be dealt with will be appreciated.” [3]

“How Nurses and Relief Workers Fought the Epidemic in Calder,” Edmonton Bulletin, Nov 15, 1918, p.3.

What could be done to help the city’s households manage and survive? Community-minded Edmontonians volunteered to help their neighbours, but the number of people who needed care was so large that relief efforts had to be coordinated so volunteers didn’t get overworked and become sick (though many did anyway) and to be sure that no one died because they couldn’t get help (though this happened too).

Two weeks into the epidemic, Mayor Evans and the city’s clergymen organized a community-care scheme which divided the city into 15 “relief districts.”

Neighbourly help in each district was provided by volunteers, most of them women, and coordinated out of school buildings. Anyone in the city could telephone their local relief district to request assistance of any kind, and the Edmonton Bulletin newspaper reported the goings-on of the relief districts in great detail. The Queen Alexandra School served as relief headquarters for everything from the CPR tracks (today’s Gateway Boulevard) westward to the river.

“On entering the office one is impressed with the systematic manner in which things are arranged. Lists are kept of those who have volunteered in any way to help and then as a case is reported the person in charge is able to secure immediately the people best suitable to render aid. Some volunteer to do chores, washing, supplying certain kinds of food or cooking food, in fact, almost every kind of assistance imaginable.” [4]

“How Influenza Is Fought At Queen Alexandra School,” Edmonton Bulletin, Nov 18, 1918, p.3.

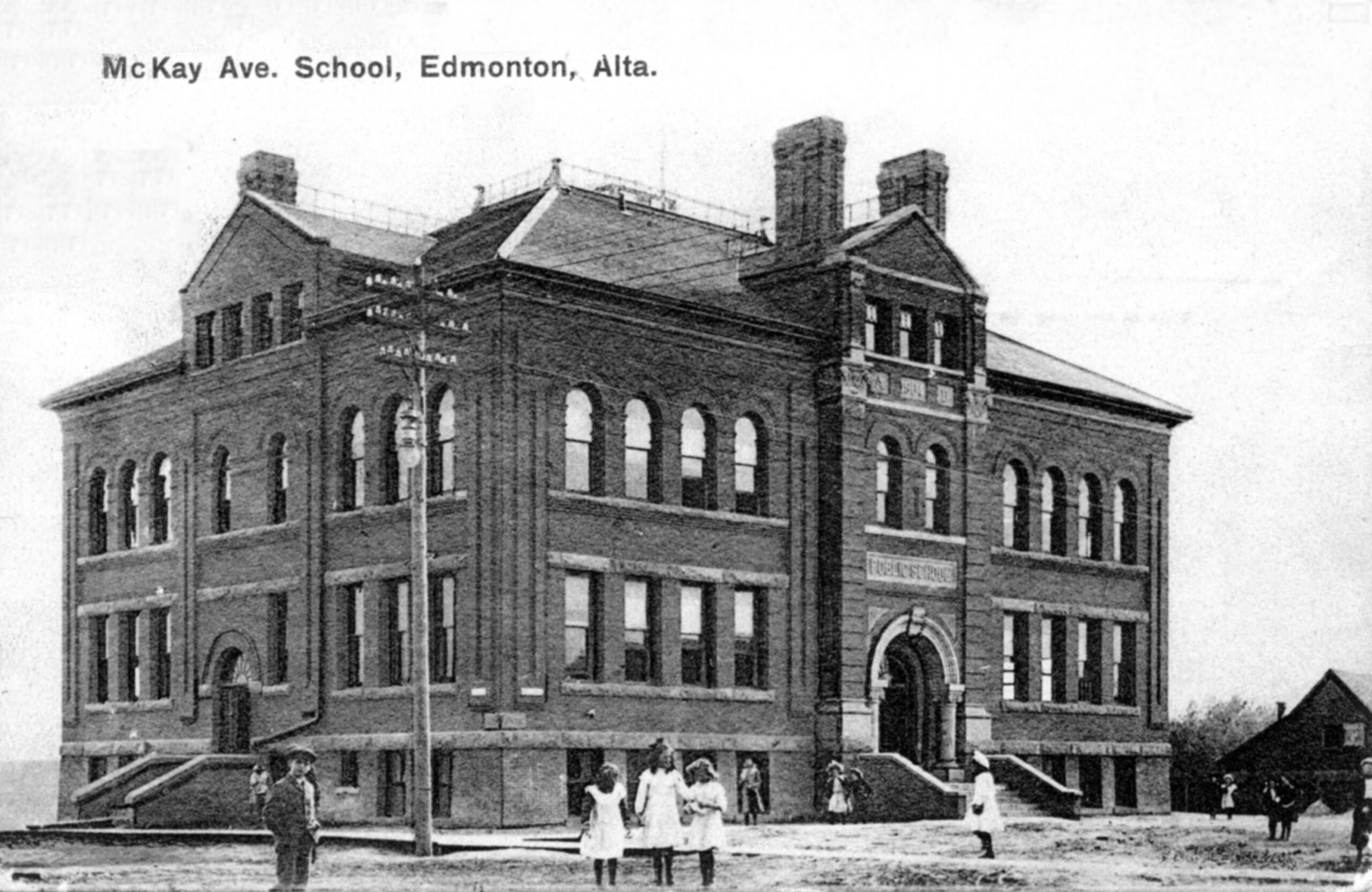

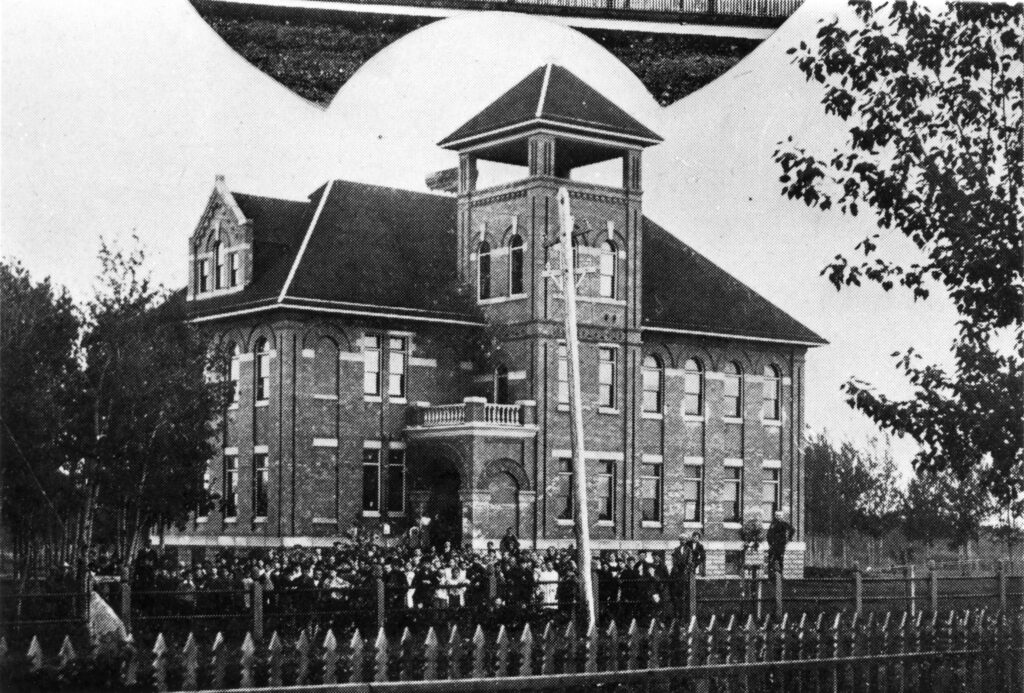

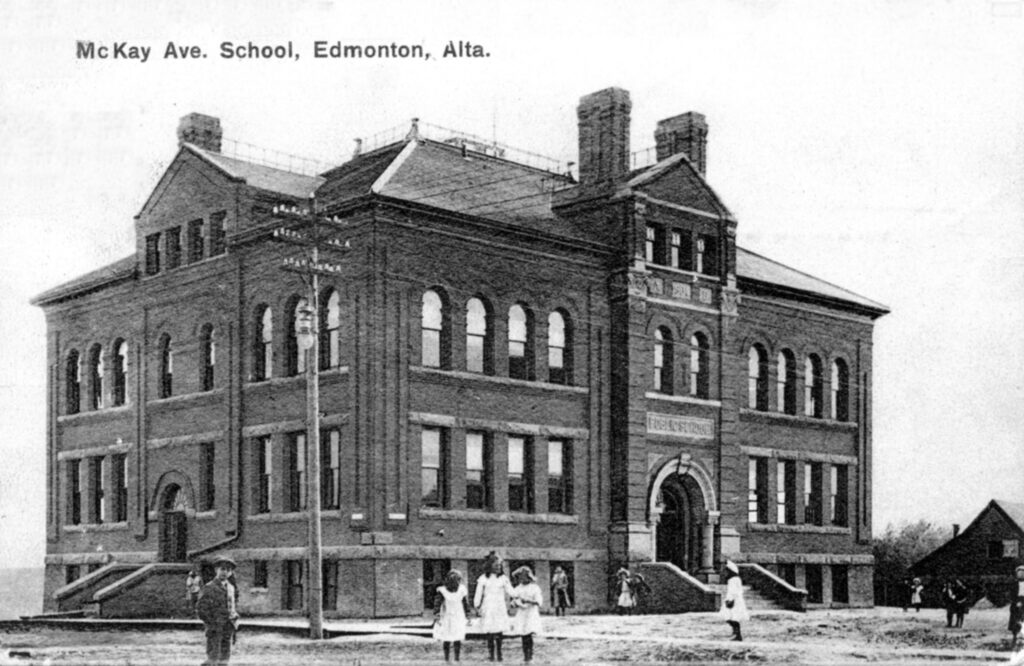

North of the river, the McKay Avenue school relief station reported that their volunteers had already responded to over 400 calls for help in the first two weeks.

“[The ladies of the McKay Avenue School relief district want] to give full and unstinted credit to the people of the district who have so nobly and generously responded to every call for assistance. Were nurses needed to care for stricken ones, they were forthcoming. Was help needed to carry on domestic establishments where the heads of the family were down with the ‘flu, it came at once. Were babies to be tended, meals cooked, rooms swept, beds made, fires lighted, ashes carried out, medicines brought, errands run, no sooner suggested than done. It has been an unfailing help.” [5]

“Relief Work Being Done at the McKay Avenue School,” Edmonton Bulletin, Nov 15, 1918, p.4.

Of course, it was not just household chores Edmontonians needed help with. Thousands required nursing care, but the enormous demand could not be met through ordinary means. The solution to the problem was found in a system of volunteer nursing similar to the 15-district neighbourhood relief plan used for household needs.

The city was divided into four ‘nursing districts’ with headquarters in King Edward, Victoria High, Calder, and Oliver Schools. There were only a few trained nurses available in the city to help with district (rather than hospital) nursing care. They took charge and provided direction to countless volunteers.

Not only were there not enough beds in hospitals, but there also were not enough nurses.

Nursing headquarters were complex organizations: the centre at Victoria High boasted not only a linen room, supply store and dispensary which provided nurses with whatever they needed for visits, but also a laundry room run by high school girls, a “disrobing room” where outdoor clothes could be changed and disinfected, day and night dormitories for the nurses and volunteers, and a convalescent room for volunteers who were recovering from exhaustion or illness. These nursing centres were very large: Victoria High had a dining room which served 100 people at each meal. [6]

The relief district organized out of Westmount School had additional challenges because this part of the city lacked some city services. Providing relief care in this district involved “a tremendous amount of work, especially as the houses are so very scattered and also as the accommodations are limited, having in so many instances no water, light and other conveniences.”[11] The relief committee also undertook some unusual chores in Westmount: “As the man who delivers water to this district has been stricken with influenza, the committee has undertaken to look after him, to water the horses, milk the cow and generally look after his welfare.”[12]

Food was an integral part of all nursing and relief centre work. Oliver School (which was especially busy because it functioned as both a relief and a nursing district headquarters) ran a kitchen and collected donations of food. Women’s domestic expertise was celebrated in newspaper reports of relief work. Oliver School’s kitchen, for example, was reported to be “under the able supervision of Miss Johnstone, domestic science teacher.”[7]

Automobiles were desperately needed to aid relief work. In the Highlands the relief centre’s “nourishment department” delivered food by automobile, sending out soup each noon and baskets of food each evening to families in need. One volunteer called Mr. Jimby, “ran his car constantly every day for a week”[13] as part of the influenza relief efforts.

Many women offered generous donations of supplies, food, and linens made in their own homes. The outpouring of support impressed the newspaper writers: “The people of the community seemed to vie with each other as to who could send the most and best supply of cooking, soups and other essentials. Many delicacies were also sent in for the nurses themselves who were doing such excellent work in helping the sick and suffering.”[8]

Although many people were eager to donate goods to help, it was not always easy to find enough volunteers to provide care in the homes of the sick. Edmontonians were understandably concerned about getting sick themselves.

The newspaper was filled with calls encouraging women (and occasionally also men) to volunteer, even comparing ‘flu volunteer work with joining the army to fight the Great War (1914-1918). One writer urged Edmontonians to overlook the danger and be heroic:

“It is dangerous- undoubtedly. So is overseas service; yet that did not hinder enlisting to any large extent. It would be better to have the ‘flu than to carry through life the uneasy feeling that by your indifference you allowed some other woman to die; or children to go hungry. If ever you intended to do a heroic thing – do it now! Phone headquarters. They’ll tell you what you can do!!” [9]

“What the ‘Flu is doing to us,” Edmonton Bulletin, Nov 2, 1918. p.3

Relief and nursing organizations were household supports, not hospital replacements. The city did have a number of hospitals, including an emergency influenza hospital operating out of the University of Alberta’s Pembina Hall. Many people who were very ill were treated at these hospitals by nurses, volunteers, and doctors. City doctors did their best to visit their patients at home and provide care. The article’s focus on the relief work hosted out of schools doesn’t mean that the professional medical and nursing establishments were irrelevant or insignificant in the “fight against the ‘flu” as the newspaper called it.

Rather, the work coordinated in school buildings demonstrates an innovative way of providing care for an exceptional volume of people who needed help. It also highlights the tremendous, but usually unacknowledged, role of caring work and domestic labour – generally provided by women- in supporting those suffering from illness.

Newspaper reports contain hints about Edmonton’s diverse population in 1918.

Instances of poverty are recorded: one volunteer reported finding a family in a ‘shack’ on 111st where the mother and ‘innumerable other children’ were sick with the ‘flu, and that in the midst of the family’s ‘flu outbreak, the mother had given birth to another baby but had no clothing for the infant.

The Edmonton Bulletin writers also remarked, albeit often obliquely, on ethnic differences in the city.

Of McCauley, he wrote, “There is a peculiarity about the district, in as much as its population is somewhat of a mixed character, boasting of a good percentage of foreign names, but in spite of this the committee has worked admirably in every respect.”[10]

References to non-white citizens are few and far between and the newspaper’s apparent surprise at cooperation between different groups suggests tensions and prejudices scarring the city.

Edmonton’s 1918 influenza story is complicated and multifaceted, but despite the multiplicity of emotional and psychological scars it left on those who lived through it experiencing fear, suffering, sickness, and death, it left very few physical traces on our city’s landscape.

(Click on the image to engage with location links, map opens in a new window)

The bulk of influenza relief and nursing care was domestic in nature and performed by women, part of an ongoing legacy of invisible, and yet absolutely essential, labour keeping households and communities alive.

During the 1918 epidemic, however, that domestic work became more visible, coordinated at schools and reported on in the newspaper. So the next time you walk through your neighbourhood and see a heritage school, think about the temporary role they played in hosting courageous groups of (mostly) women who gathered and organized to help their neighbours with nursing work, childcare, cooking and cleaning in spite of fear and the very real dangers of a deadly epidemic.

Suzanna Wagner. (2022)

[1] The 1918 influenza epidemic which affected Edmonton so severely in fall 1918 and winter 1919 was the second wave of a four-wave global influenza pandemic. The first wave- which spread across the world in the spring of 1918- was relatively mild and did not create any large-scale need for organized help or nursing care. The second and most serious wave engulfed the world from approximately September 1918 to March 1919 (the exact dates vary depending on location). After a spring and summer apparently free of influenza, the virus returned in fall 1919 to winter 1920 for its third wave, once again disappearing over the spring and summer only to come back for the fourth and final wave in fall 1920 to winter 1921. Globally, the third and fourth waves were less severe than the fall 1918 “second wave” which explains why this multi-year pandemic is often called “the 1918 influenza pandemic.”

[2] As 1918’s writers shortened the word “influenza,” they generally added a preceding apostrophe. This historical spelling as a recognition of the importance of contemporary written sources in preserving this story.

[3] “How Nurses and Relief Workers Fought the Epidemic in Calder,” Edmonton Bulletin, Nov 15, 1918, p.3.

[4] “How Influenza Is Fought At Queen Alexandra School,” Edmonton Bulletin, Nov 18, 1918, p.3.

[5] “Relief Work Being Done at the McKay Avenue School,” Edmonton Bulletin, Nov 15, 1918, p.4.

[6] It was not uncommon at the time for families in a comfortable economic situation to hire ‘private duty’ nurses to care for a sick family member at home. In the midst of the epidemic crisis, however, monopolizing the few available private duty nurses was seen as unacceptable.

[7] “Oliver Relief Centre Committee Returns Thanks,” Edmonton Bulletin, November 25, 1918, p.4.

[8] “Oliver Relief Centre Committee Returns Thanks,” Edmonton Bulletin, November 25, 1918, p.4.

[9] “What the ‘Flu is doing to us,” Edmonton Bulletin, Nov 2, 1918. p.3

[10] “Fighting the ‘Flu at the McCauley School,” Edmonton Bulletin, Nov 14, 1918, p.3.

[11] “Devoted Work at Westmount Relief Centre in Fighting Flu,” Edmonton Bulletin, Nov 19, 1918, p.4.

[12] “Devoted Work at Westmount Relief Centre in Fighting Flu,” Edmonton Bulletin, Nov 19, 1918, p.4.

[13] “Flu Epidemic Handled Thoroughly at Highlands,” Edmonton Bulletin, Nov 18, 1918, p.4.