Velva Hueston moved to Edmonton with her mother in the early 1920s, after her father died in the 1918 flu pandemic when she was sixteen.1 To support their small family, Velva became a teacher, working at Jasper Place and Cromdale Schools and caring for her mother until her death in 1942.2 Shortly thereafter, in 1943, thirty-year-old Velva married Edward (Scotty) Thompson.

In most of the twentieth and certainly the twenty-first century, Velva’s story would have continued as normal from here, with nothing loud or scandalous happening in an otherwise distinguished teaching career. But by changing from Miss Velva Hueston to Mrs. Velva Thompson in between the spring and fall terms of 1943, the veteran teacher ran up against an illegal and discriminatory policy from the Edmonton Public School Board (EPSB)—and proceeded to change the course of history for generations of married women teachers in Edmonton.

This is the story of Velva Thompson and her fight for married women to teach.

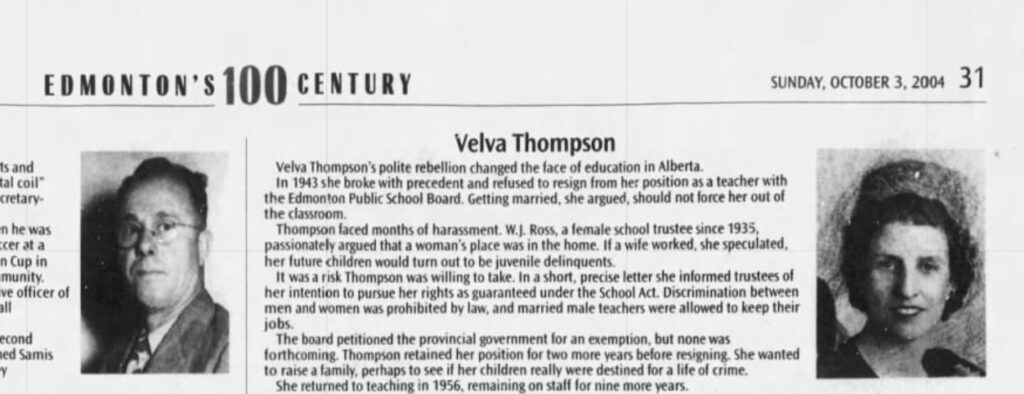

The Edmonton Journal. Page 31. Newspapers.com

A Friday phone call

A short time after the beginning of the fall scholastic year, Thompson received a Friday phone call from then-Superintendent of Schools, Ross Sheppard, informing her that she could not continue in her position as a permanent member of staff.3 The position of the EPSB was simple and clear: married women could not teach full-time. This policy had been in place since 1916. When a woman married, she resigned from her permanent teaching contract. She could reapply to work as a substitute teacher, but these positions had no guaranteed annual renewal and no incremental pay increases.4

This was the only option that Sheppard offered Thompson.5 The very fact that Sheppard had to spell this out for Thompson was unusual. “Most female teachers knew they were expected to resign as soon as they were married, and complied.”6 Men, of course, were not forced to make this decision.

A “forceful letter”7

Thompson had been prepared for this reaction. On the following Monday, she sent a short and clear letter to the EPSB Board of Trustees—not only refusing to step down from her permanent contract, but also rejecting the Board’s authority to make such a demand of her or any other married woman in the first place. She wrote, “I have sought advice on the matter and am advised that a school board has not the authority to pass any regulation requiring that women teachers upon becoming married shall automatically retire or be requested to give notice of termination of contract of engagement.”8

Thompson’s advice and support came from a number of women, including Jo MacNeill, her school’s principal (who was one of only a small handful of women principals working for Edmonton Public Schools) and Mina Johnston, the only woman serving on the Alberta Teacher’s Association (ATA) Executive at the time.9 Johnston in particular wanted to use Thompson’s case to advance the rights of women within the ATA, where her male colleagues were sympathetic to Thompson’s situation—but not on the grounds of equality between women and men. The men on the ATA Executive were more concerned about the question of tenure (that is, they believed that Thompson should not have her existing contract terminated unlawfully), with some even agreeing that married women should not be hired in the first place.10

In any case, Thompson framed her response to the EPSB directly along the lines of gender equality: “… with all respect I must take the position that it is my intention to abide strictly by my rights under the contract and under The School Act, which does not permit any discrimination as between men and women (Section 246).”11

The Board reacts

The reaction to Thompson’s letter was swift and loud, with “disapproval and harassment from both men and women.”12

“The superintendent never called me [again] but I did receive several calls from a senior secretary in the office telling me what an awful thing I was doing, and if I insisted on staying they could send me anywhere in the system,”13 recalled Thompson.

The continued harassment only strengthened Thompson’s resolve.14 She recalled in a later interview that initially “she had no intention of stirring up any trouble; she was hoping that the School Board would leave her alone and she would be able to continue to teach at her school.”15 Indeed, we can see this no-nonsense attitude in both her direct and precise letter, and also in the historical retellings of her story—one of which calls her letter “polite, but firm,”16 another of which dubs her whole struggle with the school board a “polite rebellion.”17

The emphasis on Thompson’s politeness in retellings of her story is patronizing – as if she only won her battle by being good-mannered and well-behaved to her oppressors, and a nasty woman would not have deserved to have her rights recognized. It also points to Thompson’s specific position in society and her privileges as a white, middle-class woman; she had the ability to push back within the formal channels of the colonial education and legal systems and be taken seriously. It’s easy to imagine other women with more marginalized identities being less successful, were they even to be employed as teachers in the first place.

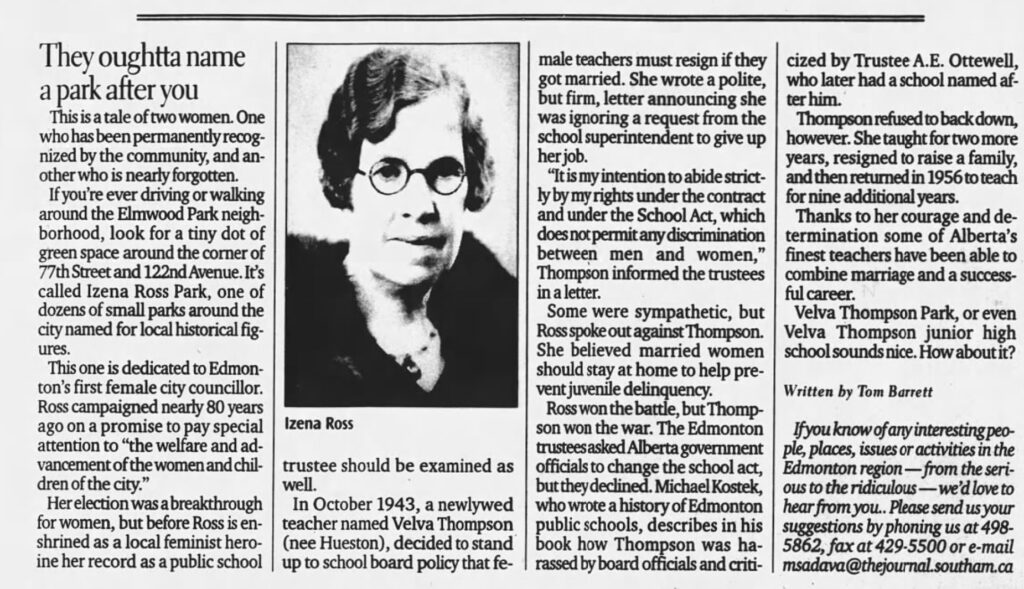

Much of the historical record highlights one critic of Thompson in particular: Izena Ross, a school board trustee from 1935 to 1945. She had herself made history twenty-two years earlier, when she became the first woman elected to Edmonton’s city council.18 That ground-breaking attitude seemed to disperse when she took her position, however, as Ross “passionately argued that a woman’s place was in the home. If a wife worked, she speculated, her future children would turn out to be juvenile delinquents.”19

That Ross’ opposition is often highlighted in historical profiles and retrospective articles also says more about the tellers of this story than their subjects, considering that several other male school board trustees were also upset by Thompson’s letter. This included Albert Edward Ottewell, who Thompson recalled having a particularly flabbergasted take: “Keeping house is a full-time job. School teaching is a full-time job. Married women school teachers must be a race of superwomen.”20

Ottewell has a school named after him,21 and so does Ross Sheppard. Velva Thompson has not yet received the same honour (nor has Izena Ross, for that matter).

The EPSB tries to change the law

Despite their displeasure with Thompson, the Board recognized that in this case their hands were tied. Mrs. Velva Thompson would be allowed to teach; however, they weren’t about to let any more women march through the door that Thompson had kicked open. The Board resolved to ask the provincial government to amend the School Act, requesting an explicit exemption to discriminate against married women:

“Whereas this Board is of the opinion that it is in the best interests of family life and the community in general that a married woman teacher should not continue to hold a permanent appointment, terminable only at her own pleasure, THEREFORE, BE IT RESOLVED: That the Minister of Education be requested to so amend the Alberta School Act to provide that any School Board may terminate, upon marriage, the contract of any woman teacher who marries while holding a continuous contract with the Board.”22

In November 1943, the Board brought this resolution to the Alberta School Trustees Association (ASTA, not to be confused with the Alberta Teachers’ Association), who approved the resolution and sent the request to the provincial government in January 1944 on behalf of all the school boards in Alberta. They even provided their own draft amendment, a simple 42 words that the Ministry of Education could cut and paste into the School Act, nullifying the rights of married women teachers across the province:

“Notwithstanding any of the provisions of this Act a Board may terminate the contract of employment or the engagement of any married women as a teacher by giving such married women thirty days notice in writing of its intention to do so.” 23

Unfortunately for the EPSB and ASTA, there had been another recent case that reaffirmed the gender equality language of Section 246 of the School Act. In July 1943, a judge had ruled in favour of a woman teacher who was being forced to retire at 60 (men could work until they were 65), plainly stating that “Section 246 of the School Act really did mean what it was intended to mean.” 24

This decision reinforced the position of Thompson and her allies, making it clear that the law was unambiguous. The provincial government dismissed ASTA’s requested amendment, allowing other women to follow the trail that Thompson had blazed.

Thompson’s case was also aided by the historical moment in which she chose to take her stand. With World War II still raging in Europe after four years, there were severe labour shortages in Canada, including in the teaching profession.25 Schools were understaffed, and the availability of better-paying jobs led to enough teachers quitting that the federal government mandated that no teacher could leave their post unless they were enlisting in the armed forces in June 1943.26

Following her victory, Thompson stayed on as a teacher for two more years. She then took 11 years off to raise a family—her own choice, on her own schedule. She returned to teaching in 1956 and taught for another nine years at Coronation and Westminster Junior High School before retiring for good.27

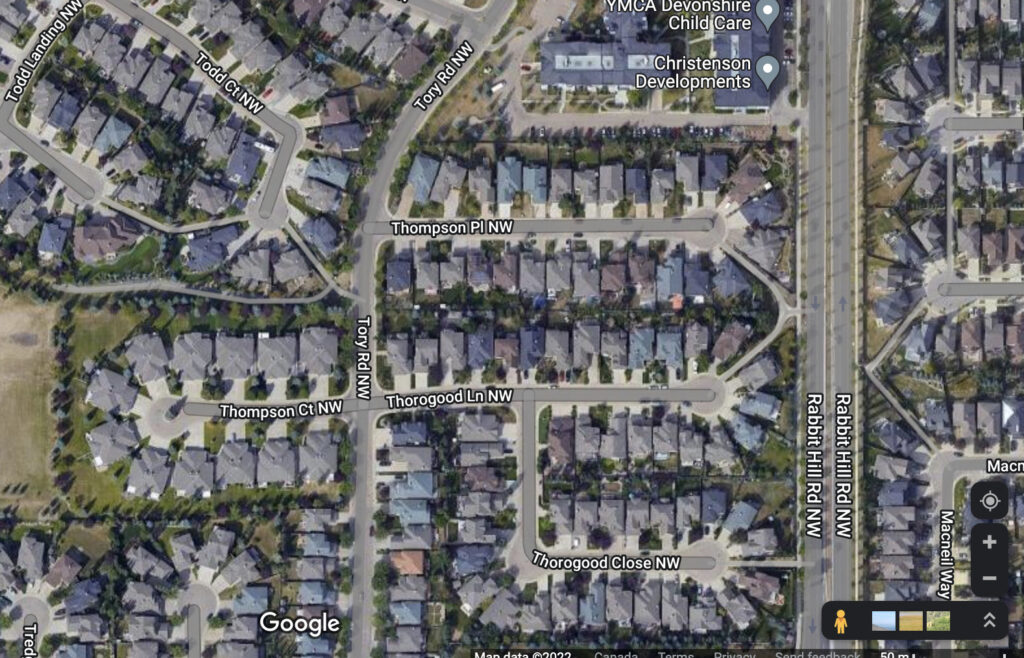

While she still hasn’t had a school named after her, the City of Edmonton eventually added Thompson’s name to its reserve list,28 leading to two small roads named after her in Terwillegar. 29

Perhaps the most striking part of Velva Thompson’s story is how simple it is. Our history is full of heroes who are rightly celebrated for the years and decades of struggle and sacrifice that they undergo to achieve their goals. Thompson, by contrast, wasn’t an experienced, lifelong activist. She didn’t fight for a change in legislation or organize a grassroots political movement or lead a campaign with massive protests to overturn an unjust law. She simply looked at the law as it already existed, knew her rights, and had the audacity to insist that her society actually live by the ideals that they’d committed to on paper.

Thompson ultimately successfully resisted pressure to resign, arguing that she had the right to remain in her position under the provincial School Act (which nominally promised non-discrimination based on sex, although the culture remained sexist as ever).

As such, her story holds a powerful lesson for all of us. Anyone could have done what Velva Thompson did. It just took someone with her courage to risk rocking the boat a little bit, to be the first to take a stand.

Bruce Cinnamon. (2022)

REFERENCES & RESOURCES

[1] Velva Thompson (1903-1993). Edmontonians of the Century, 2004, page 77.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Velva Thompson’s letter to the Edmonton Public School Board of Trustees, 4 October 1943. As excerpted in A Century and Ten: The History of Edmonton Public Schools, 1992. Michael Kostek. Page 340. Available through EPSB Archives and Museum.

[4] Women Teachers in Edmonton Public Schools, 1940-1950. Collette Alice Oseen. University of Alberta, Fall 1985. Master of Education thesis. Page 147. Available through University of Alberta Library. – “In contravention to the Provincial school Act, from 1916 onward EPSB followed the policy that upon marriage a woman must resign her position. Married women teachers could only reapply as substitute teachers; their positions were renewed annually and they received no increments.”

[5] Velva Thompson’s letter to the Edmonton Public School Board of Trustees, 4 October 1943. As excerpted in A Century and Ten: The History of Edmonton Public Schools, 1992. Michael Kostek. Page 340. Available through EPSB Archives and Museum.

[6] A Century and Ten: The History of Edmonton Public Schools, 1992. Michael Kostek. Page 340.

[7] “Fact #117 – Women’s History Month & Velva Thompson. 140 Years 140 Facts, 2021. Available through EPSB Archives and Museum.

[8] Velva Thompson’s letter to the Edmonton Public School Board of Trustees, 4 October 1943. As excerpted in A Century and Ten: The History of Edmonton Public Schools, 1992. Michael Kostek. Page 340.

[9] Women Teachers in Edmonton Public Schools, 1940-1950. Collette Alice Oseen. University of Alberta, Fall 1985. Master of Education thesis. Page 151.

[10] Ibid. Page 152.

[11]A Century and Ten: The History of Edmonton Public Schools, 1992. Michael Kostek. Page 340. Available through EPSB Archives and Museum.

[12] Naming Edmonton: From Ada to Zoie, 2004. The City of Edmonton. Page 304.

[13] A Century and Ten: The History of Edmonton Public Schools, 1992. Michael Kostek. Page 340. Available through EPSB Archives and Museum.

[14] Women Teachers in Edmonton Public Schools, 1940-1950. Collette Alice Oseen. University of Alberta, Fall 1985. Master of Education thesis. Page 151. Available through University of Alberta Library. – “However, the badgering of Ross Sheperd [sic], the superintendent, who threatened to move her anywhere in the city if she did not resign, and the support of MacNeill and Johnston, prompted her to allow her name to stand.”

[15] Ibid. Page 151.

[16] “They oughtta name a park after you.” Tom Barrett. The Edmonton Journal, 16 November 1999, page 18.

[17] “Velva Thompson.” The Edmonton Journal, 3 October 2004, page 31.

[18] “They oughtta name a park after you.” Tom Barrett. The Edmonton Journal, 16 November 1999, page 18.

[19] “Velva Thompson.” The Edmonton Journal, 3 October 2004, page 31.

[20] A Century and Ten: The History of Edmonton Public Schools, 1992. Michael Kostek. Page 340.

[21] “They oughtta name a park after you.” Tom Barrett. The Edmonton Journal, 16 November 1999, page 18.

[22] Women Teachers in Edmonton Public Schools, 1940-1950. Collette Alice Oseen. University of Alberta, Fall 1985. Master of Education thesis. Pages 149-150.

[23] Ibid. Page 150.

[24] Ibid. Page 149.

[25] Ibid. Pages 148-49.

[26] Ibid. Page 148.

[27] Velva Thompson (1903-1993). Edmontonians of the Century, 2004, page 77.

[28] “Pioneer against sexual discrimination lauded by council.” Ron Chalmers. The Edmonton Journal, 28 July 2001, page 21.

[29] Naming Edmonton: From Ada to Zoie, 2004. The City of Edmonton. Page 304.