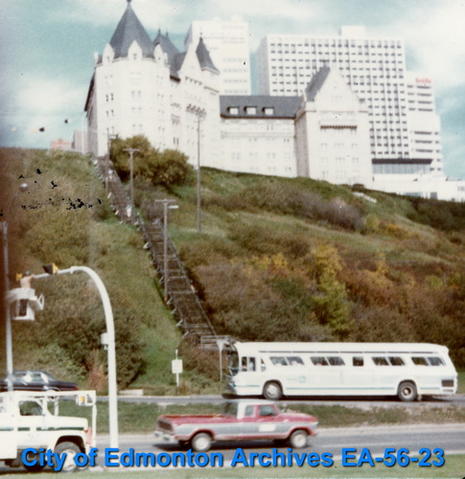

MacDonald Drive has overlooked the river valley from Edmonton’s earliest incarnation, marking the south edge of downtown, a steep bank plunging to the valley below. A very short piece of road (only two blocks in length), it’s prominent in many of the early black and white cityscapes of downtown. The grand Hotel Macdonald marks its eastern end, and the water tower that rose on thick steel pillars behind the Edmonton Journal building marked the other end, before unceremoniously ending at 102 street. This was the end of downtown, with no way down but steep paths. One block from the actual city centre, it was for all intents and purposes, the end of the road.

It was a dignified strip of Edmonton real estate in the daylight, hosting the elegant Edmonton Public Library, and the burgeoning Alberta College campus, as well as the stately McDougall Church.

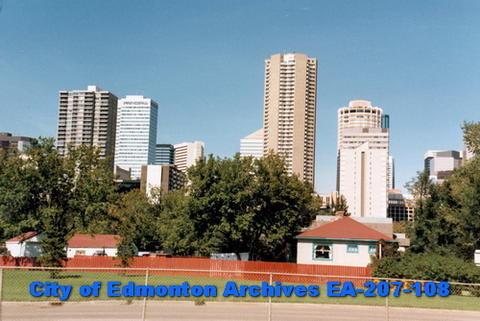

In 1966, the edge of the downtown riverbank began a radical transformation with the addition of the Edmonton House tower, followed in 1969 by the Chateau Lacombe, and the new Bellamy Hill Road plunging between hotels to the floodplain below. The Edmonton Public Library was razed to make way for two giant AGT towers, the tallest of which was completed in 1971 (for years, the tallest building in Edmonton).

It’s difficult to determine when exactly this strip of downtown became known as a place for gay men to meet, but by 1969 the short strip of road already had a reputation, indicated by a unique document that was making the rounds in Canada – a guide to being gay in Canada, created and compiled by Roedy Green, leader of the Vancouver chapter of Gay Alliance Towards Equality. The Naive Homosexual was an unofficial handbook to assist gay men struggling with questions about being gay.

This amazing document contained something that must have been a momentous discovery for the lucky folks who were able to get their hands on it – listings of all the locations in Canadian urban centres where LGBTQ2S+ people could safely and discretely meet others like them.

Through the 1970s and even into the early 80s, it was not only a place to meet potential sexual partners, but it was also a place to buy and sell sex. Depending on the year, sex workers of various genders could be found lining the sidewalk.

MacDonald Drive had attributes that made it perfect for such an activity: all the buildings that lined the street were closed at night; there were only buildings on one side which meant far less chance of being surprised by someone appearing for violent purposes; and it was a one-way street starting in 1971, which meant the cruising car traffic moved in one direction circling repeatedly. Sex workers and cruisers alike could worry less about who was approaching behind them.

It is no surprise that the closest apartment buildings – The Arlington, The Pallisaides, the towers on 104 Street, and the Avord Arms a few blocks north – were filled with renters from the LGBTQ2S+ community, because this whole area took on a very queer flavour as downtown relaxed into its 70s persona. Even the first Empress of Edmonton resided with a gaggle of queens in a large rental house at the bottom of Bellamy Hill.

The newly-built hotels added travelling strangers to the mix. Gay travellers staying at the Hotel Macdonald, the Chateau Lacombe, Edmonton House or even the adjacent Greenbriar, found that the opportunity to discretely sample the locals was simplified by the proximity to an active cruising area right across the street.

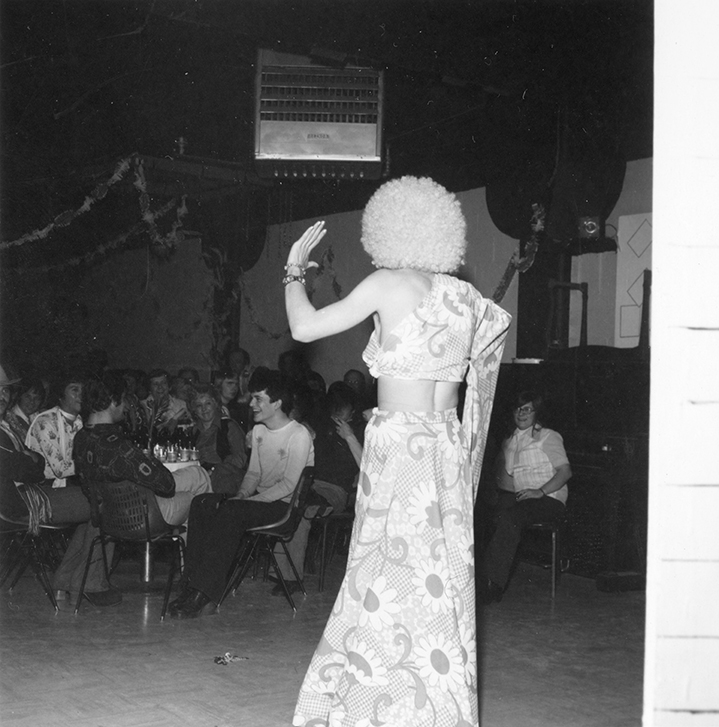

In the 70s, the reputation of this strip grew, becoming not only a place for cruising for and selling sex, but it also a gathering place after the only gay bar in town – Club 70 – closed for the night. Revellers would head to The Hill and socializing that occurred into the wee hours. On weekend nights several groups could be seen hanging out in different spots, socializing, as the traffic circled past – sometimes stopping just to visit and gossip with the groups on the sidewalk. It would not be out of the question to witness a drag queen or two strolling post-performance, audaciously strutting her stuff. There was safety in numbers.

The actual cruising zone moved, shifted and morphed over the years as police “cleanups” pushed the action around. For a while, The Hill would be empty because the cruising had moved a block or two west, taking root in the alleys between 102 and 104 Street, or the nearby parkades. Sometimes the action was centred around Veteran’s Park across from the Edmonton Journal. In the late 1980s, 104 Street was where the straight men cruised, and The Hill was where the gay men cruised, but – all things being relative – all kinds of cruising occurred in all the alleys between those locations.

The late 70s-early 80s were undoubtedly the heyday of The Hill. By 1978, Edmonton had 3 gay bars and many gay organizations. That was also the year that the Pisces Spa opened, adding another all-night option for the socializing gay male.

In 1980, The Dapple Gray Cafe opened on 102 Street at the spot where MacDonald Drive ended, creating an all-night bright moment on a dark stroll for those less inclined to cruise on the street, as well as a safe place to escape to if things got scary. Higher visibility for the community that used The Hill meant there were moments of danger. The heightened activity had some dark consequences.

In the summer of 1980, warning posters went up on the lampposts lining the area. Gay Alliance Toward Equality (GATE) was asking gay men not to hang out at The Hill anymore, or at least cautioned vigilance, because incidences of antigay violence were on the rise. There are reports of van-loads of gay-bashers arriving on the scene, pouring out of vehicles, armed with chains or baseball bats, sending cruisers scattering into the dark alleys, away from the danger. There are also reports of the queers fighting back, chasing homophobes away.

Mark – the guy with the white eyebrow – was famous on The Hill and had not only a large following but some influence over some of the rougher characters that populated it. He had been working there since his early teens and recalls the legendary rumble that occurred circa 1980.

“I was there the day that the last set of f*ggot beaters marched down to the Hill, in a group of about 50 to 75 – from the hood, and the hood back in my day was down at 95th Street. They would come down to the Hill to beat the f*gs up. We all used to sit on the steps where the McDougall Church was, right on MacDonald Drive. There were steps for the side entrance of the church, and we all used to sit there. It was kind of like a congregation spot for all gay people. And I remember being there one day, and there was a couple of queens there, and all the hustlers. And we heard a rumour that there was a group of 75 people coming down. They were going to beat us fags senseless. So, everybody grabbed whatever they could for a weapon. Like, we’re pulling up chain link fence rods right out of the earth. Anything that people could get – two by fours, broken bottles… I remember one Queen – he had just bought a pair of these clog high heels. Can you imagine how hard it is to break? He totally took his shoe, and he wrecked his shoe beating it over this guy’s head.”

That may have held off the gaybashers for a spell, but the violence wasn’t over.

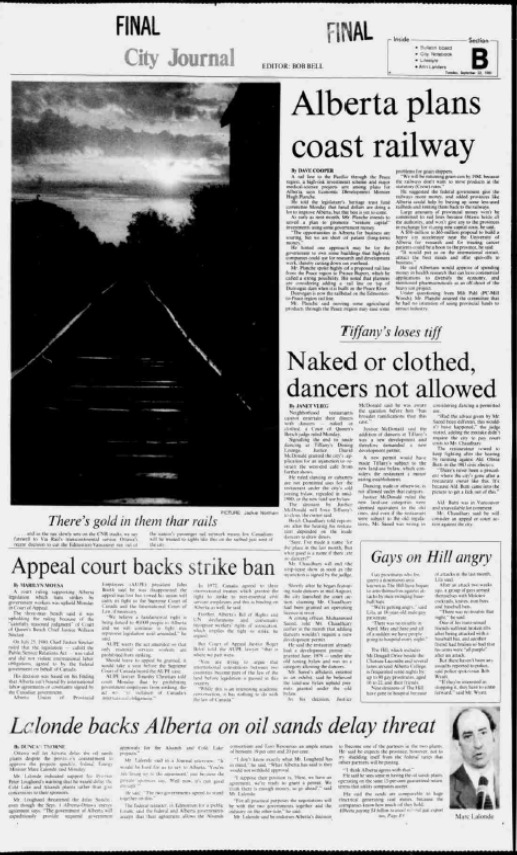

In 1981, the city had been regaled with nonstop negative media coverage of the gay community because of the hysteria surrounding the Pisces bathhouse raid. This heightened visibility led to an adverse reaction, and in September of 1981 the Edmonton Journal ran a story called “Gays On The Hill” which told of a series of gaybashings involving men swinging baseballs bats, leading to 9 cruisers and sex workers requiring hospitalization for the injuries sustained during violent attacks. In an interview with one of the sex workers, it was reported that denizens of The Hill had begun to arm themselves with knives, iron bars, baseballs bats and Molotov cocktails. The 18-year old sex worker said, “We’re getting angry. There was no trouble in April, May or June and all of a sudden we have people going to the hospital every night.” (The intense coverage of the Pisces Raid in both newspapers and every TV and radio station began on May 31 and had been running all summer.) Injuries included broken ribs, purple bruises covering one trans sex worker’s arms, and one man was hospitalized with severe skull injuries.

Police spokesman Bob Wyatt told The Journal that no attacks had been reported to police. “If they’re interested in stopping it, they have to come forward.”

Despite the violence, The Hill retained its dark allure. Things were still active in the mid-80s, although the party had gone indoors to the three gay bars that Edmonton now boasted, one of them open as late as the after-hours party spots that peppered downtown.

In 1986, the gay community learned that a staff member at Flashback had been murdered by a trick that he had taken home after his shift at the bar. Several patrons at the club had seen the man Louis Verseghe had left with – one of them was one of Edmonton’s drag queens, Lori St. John (John DeCarlo). Later that week, DeCarlo was on his way to work at Appleby Restaurant (formerly the Dapple Gray). Cruising past The Hill on his route, he spotted the murderer that he had witnessed leaving Flashback two nights earlier. The murderer was posing as a hustler, so DeCarlo pretended to be interested and talked the man into joining him at Appleby’s. Once the man was seated, DeCarlo excused himself and used the restaurant’s phone to call the police. The murderer was found guilty, and later that summer, at the annual Coronation Ball, DeCarlo was honoured by the community with a special citation for bravery.

In 1990, the shocking and violent story of sex worker Matthew Boyes grabbed headlines. He was picked up in a cab by 51-year old Patrick Haas – a client he knew from an earlier encounter – and went to Patrick’s downtown apartment. A neighbour testified that she heard a loud argument around 2 AM. An hour after that, Boyes was in a late-night downtown restaurant near The Hill, in an upbeat mood, and told the waitress he had just killed someone. She noticed blood on his hands. Later that evening, he assaulted a man who was looking for a taxi, and was picked up by police, charged and released. Back at Patrick’s apartment, a friend noticed that Patrick’s newspaper hadn’t been picked up and became concerned. He opened the apartment door and saw blood in the room and Boyes sleeping on the couch. He called police, who arrested Boyes. Also in the apartment, in the bathroom, was the body of Patrick, dead from 22 stab wounds. Eventually Boyes entered a guilty plea to manslaughter, and was sentenced to 8 years in prison, with the judge remarking on the “brutal, savage, senseless butchery” of the attack.

By the mid-1990s, anti-gay violence was one of the many reasons street cruising began to wane. The AIDS epidemic was also striking this city with a vengeance. There could still be hustlers found on The Hill, and homophobic violence still occurred – sometimes in reaction to big news stories about gay rights – but cruisers found other ways to mingle. Access to the internet transformed the way men connected for sex, and today the area is a quiet and picturesque street with historic information signs. Even for those who were there decades ago, it’s difficult to imagine how the strip appeared when it was a magnet for late night club-goers, on the hunt for a different kind of scenery.

Today, high above the smooth quiet river and the ever-present traffic maze, the view of the valley can still impress.

Darrin Hagen © 2022

See also: ECAMP Podcast S02E01 | Heritage Trees & Gay Cruising in the 1980s by ECAMP podcast | Listen online for free on SoundCloud