The 1821 merger of the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) and the North-West Company (NWC) harkened an era of unfettered commerce and aspirations of permanency across the continent. Trail construction at Athabasca Pass, leading to points west via the Columbia River, bolstered the importance of Fort Edmonton as a major player in the transcontinental movement of goods. Recognizing its strategic placement along the Hudson Bay bound, swiftly flowing super-highway, the company designated Edmonton the headquarters of a newly crowned Saskatchewan District.

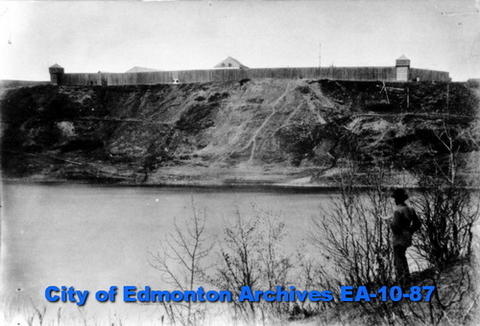

With the surge in the Fort’s prominence, as though to test human roots freshly set, the river gave warning. In spring of 1825, the North Saskatchewan tendered a mighty deluge; within hours glacial water rose clear across the river flats. Gathering what they could, the entire community clamored to the high banks above. They watched the waves amble across their freshly turned gardens, across grain fields and through buildings. Early hay for the horses drowned in the wash out; all the timbers stored for boatbuilding floated away. Some say it was an ice jam that caused the surge. Indigenous folks remarked they’d never seen the flow so high. The river was so rageful that brigades returning west from York Factory faced newly emerged sandbars and other, unperceivable dangers below the surface of the milky churning water. For Chief Trader John Rowand, the flood was an encompassing reminder of the river’s potency and a noteworthy occurrence to mark the birth of another daughter.

Image courtesy of the Archives of Manitoba, C1875, N21448.

Marguerite Rowand, sometimes recorded as Margaret, was born in late summer of 1825 amidst the reconstruction of the waterlogged Fort. After the flood, trees closest to the riverbank stood partway in the wet for a time. The inundated stockade walls and log hewn buildings were upright in most places but thoroughly saturated. The space was uninhabitable. Accordingly, families and fort employees raised tents on the bluffs above. The last weeks of Louise’s pregnancy with Marguerite were spent in this canvas community perched over the soggy flats. With John away at York Factory all summer, Louise and her children John Jr. (13), Sophie (10), Alexander (8), Nancy (6) and Henry (4) were reliant upon the network of kinfolk through this liquescent calamity. Once the water abated, everyone worked through the summer evenings to ensure the refurbished Fort was stocked and winterized. Louise, although full-term, would have carried her share of the work with grit and enthusiasm.

Marguerite Rowand was only a babe when her father became HBC Chief Factor in charge of a district covering much of present-day Alberta and a good portion of Saskatchewan. John Rowand was known to be a stern and industrious master at Edmonton House, wielding his power with equal measures good judgement and grand ambition. As a father, John was recorded as warm and protective toward his children– his daughters, especially. Louise and her husband understood their younger daughters were growing up in an era of great change for women; the eldest sisters were of the land, skilled by their grandmother’s hands to subsist and quite capable in guiding their fur trading husbands about the continent. The younger daughters were skillful too, but in new ways; their mother-tongue of Nēhiyawēwin (Cree, ᓀᐦᐃᔭᐏ) remained the primary mode of communication, but Michif, French and English were making headway in their linguistic matrix. Before mid-century, the younger Rowand daughters would read and write — literate women whose roles were also becoming increasingly domestic, hedged in by European social norms. The Rowand sisters knew the lore of the land, but they also learned to manage a large household and excelled at needlepoint. Marguerite knew how to skin a rabbit as easily as she could recite a poem, her array of talents shaped by a social and cultural world that was rapidly changing.

The last half of the 1820s was a soggy affair, as the river kept reminding folks of their precarious arrangement. Another deluge occurred in 1827. And in 1830, the river washed away the foundations of the growing village once again. A half decade of flooding finally convinced Marguerite’s father to move the entire structure up the hill for good. Permanent footings two hundred feet by three hundred feet and twenty feet high were set on an upper terrace with a clear view of the river below. It took some years to build the grand Fort as it is shown on postcards and in paintings. By the time Marguerite’s sister Adelaide was born, in winter of 1832, Edmonton had become a bustling little berg on the prairies. With its population swelling each spring and autumn as the York boats arrived from forts beyond, the HBC hustled its trade of dry-meat, boats and fur throughout the 1830s. The Rowands were surrounded by a community of mixed and Métis families, all connected by business, marriage, and cultural alliances. Celebrations to mark births, deaths and holiday occasions were lively affairs resplendent with food, fiddles, and jigs.

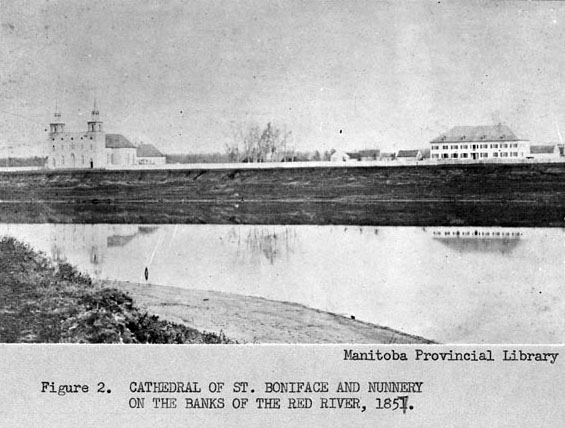

Although Marguerite’s parents were not especially religious individuals and were never married by the church, it was the social standard at the time to educate one’s children more formally as there weren’t many teachers on the continent. Thus, the Rowand daughters were likely sent to the girls’ school at St. Boniface convent, a Roman Catholic institution at Red River Settlement. HBC sons often went to Red River Academy which later to became St. John’s College. The distance by trail and waterway was approximately 900 miles (1,450 kms) on horseback, York boat or ox cart. It was a formidable journey through woodlands deep enough for an ambush and grassland skies so wide the brightness made one wince. Young Marguerite traversed these terrains many times. That first year she would have been quite little, a tear-stained cheek resting on her sister’s shoulder as each pull of the oar marked a mile further from home. Settling into hard-soled shoes, scratchy wool blankets and endless church sermons would have been quite a change for a small person. It was always an adjustment at the end of the term too. As the homeward bound cart squealed onto the rutted westbound trail, Marguerite must have wondered if she’d always be moving, then standing still, then moving; forever shifting spaces? The cycle of school seasons kept on until that terrible day in 1835, when an accident killed Marguerite’s teenage brother Henry. Compounded by the deaths of the eldest daughters, Madelaine in 1833 then Marie-Anne earlier in the year, their father was quite shaken and arranged for the children to return to Fort Edmonton immediately. Marguerite, now 10 years old, was escorted home with sisters Sophie (20) and Nancy (16). The daughters returned to find construction of the ‘Big House’ in full swing. Soon it would be furnished, complete with fine bone china and glass windows shipped across the prairies in a matrix of molasses. It was their very own metropolis, their Fort Sans Pareil.

Jenna Chalifoux © 2021

Further Reading and Sources

Reade, Dylan. “The Inundation – The North Saskatchewan Flood of 1825.” Alberta History, vol. 68, no. 2, spring 2020, pp. 2+. Accessed 24 Nov. 2021.

Flood Frequency Analysis North Saskatchewan River at Edmonton https://open.alberta.ca/dataset/027ef1fa-fe2a-4ac9-8e1b-b5425a25131b/resource/04a75f46-f251-4593-8f4a-c7dd0e2552f4/download/flood-frequency-analysis-north-sask-river-at-edmonton-1990.pdf

High and Dry (Interactive Map) https://www.arcgis.com/apps/Cascade/index.html?appid=0beff069efb34f68af2c195c3e2a8746