One hundred years ago my father stepped onto Canadian soil for the first time. It wasn’t until he passed away in 1988 that I researched how he came to stay grounded as a market gardener in Edmonton.

China was in turmoil in the mid-1800s with food scarcity, economic instability, crime, and political unrest. Dreams of a better life led to a mass departure to so-called lands of opportunity – referred to as “Gold Mountain 金山” triggering large-scale immigration to Canada with the gold rush in 1858.[1]

Between 1881 and 1885 a large influx of 17,000 Chinese labourers were recruited for the construction of the British Columbia portion of the Canadian Pacific Railway. Once Chinese labourers were no longer needed, the BC and federal governments passed discriminatory legislation aimed to keep the Chinese out of Canada.[2]

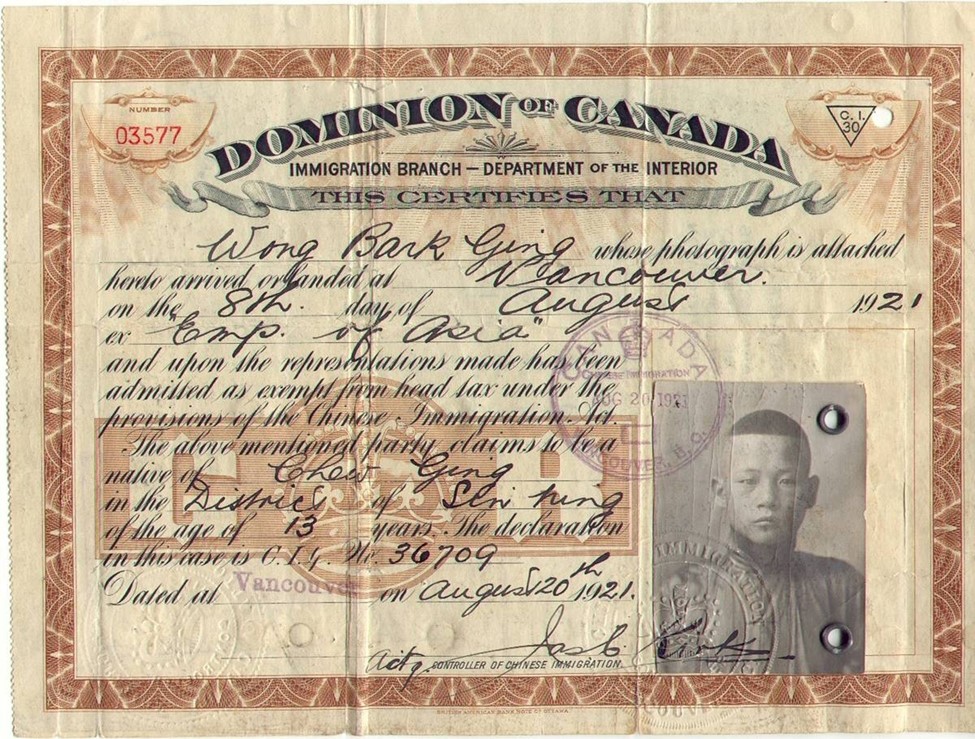

My father was born in the impoverished county of Hoisan 台山 (now Taishan) in southern Guangdong province in China often referred to as the “First Home of the Overseas Chinese.” Traditionally the oldest boy in Chinese families was destined to take care of his parents in their old age. My father, Wong Bark Ging 黃柏振, was the third-born and because he was the oldest son, he was chosen at age 13 in 1921 to go to Canada. Luckily, he was sponsored by a well-off merchant family otherwise he would have suffered along with the rest of his family.

Chinese intolerance was rife when my father arrived in Vancouver. The passenger list of the Empress of Asia showed that he was detained, it was only because he was listed as a student on the ship’s manifest and as a merchant’s son in the General Register of Chinese Immigration that he was spared from paying the onerous $500 head tax.[3]

After passing medical exams and interrogation at the immigration station, the merchant, who had eight children of his own, took him into his care. It is likely that my father initially worked as an unskilled labourer. He had little, if any, formal education in Chinese and none in English. Fortunately, his sponsor recommended he take English classes to get a grasp of this foreign language.

On July 1, 1923 the Chinese Immigration Act was enacted to functionally ban all Chinese from entering Canada and became known as “Humiliation Day” to the Chinese.

Now fifteen years of age, my father’s future became more uncertain. He may have wished to return home, but his meagre earnings could do little more than sustain himself with food and shelter. His mindset had to be in survival mode. Undeterred with his limited English skills, he had enough confidence to strike out on his own. By 1924, my father was in Alberta, taking a circuitous route working in mining camps, cookhouses and farms. In his farming village in China, my father would have gained some experience growing food – an advantage in becoming a market gardener here.

He worked and sent remittances home to help his family whenever he could. Eventually news came that his family arranged a bride for him as was the custom at the time. He had enough savings to return to his ancestral village in 1930 to marry Young See.[4] However, because of the Chinese Exclusion Act, he returned alone in May 1931 into Canada’s Great Depression with up to a third of the labour force out of work.[5]

Anti-Chinese sentiment and limited economic opportunities meant that Chinatowns supported each other with food, shelter and social activities. Chinatowns were a space protected from much harassment experienced by the Chinese outside of Chinatown.

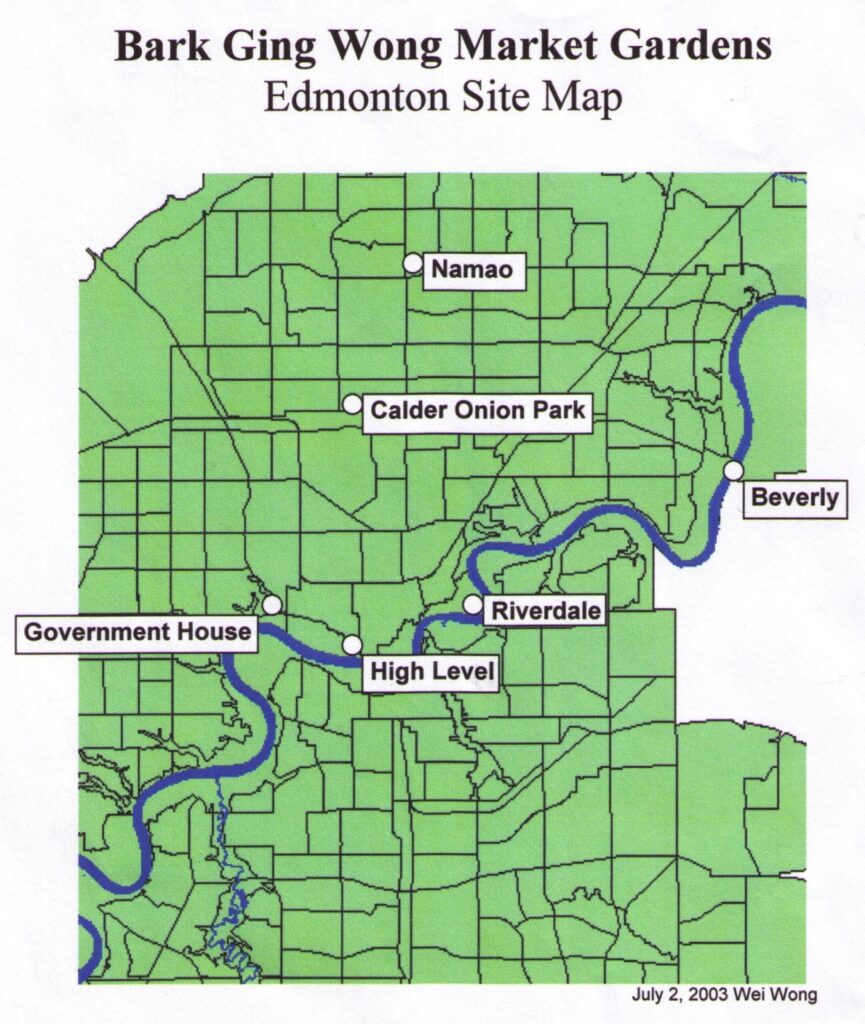

Market gardening offered men like my father a bit of independence – to be their own boss and take control of their own destiny. Away from the stifling quarters of Chinatown, Bark Ging lived on the land where he gardened, along the fertile banks of the North Saskatchewan River. Chinese market gardens operated on both sides of the North Saskatchewan River; countrymen Gee Gut farmed in Walterdale and Hong Lee had a market garden adjacent to the Victoria Golf Course.[6]

I was intrigued when our family physician, Dr. Max Dolgoy, told me that my father was one of his earliest patients and that he worked on a market garden south of the General Hospital near the High Level Bridge. Local historian Tony Cashman recounted in his article entitled High Level the Bridge That Refuses to Fall that “the Royal Glenora Club sits on the site of the former Chinese market garden.”[7]

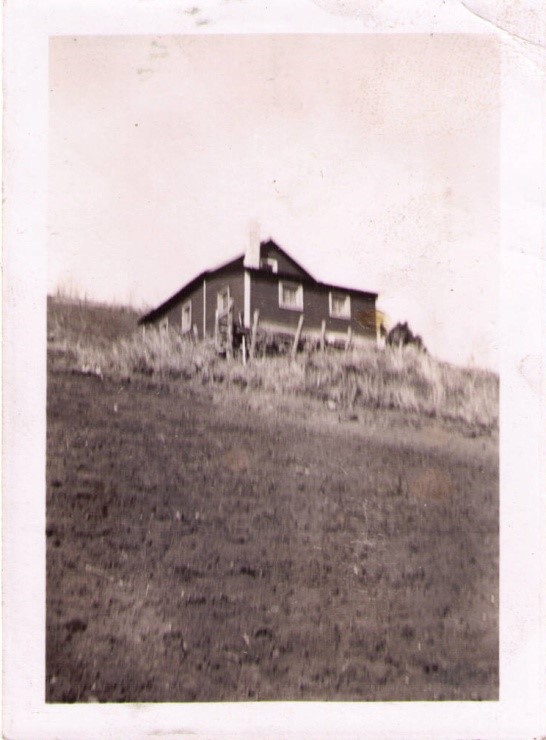

When World War II started in 1939 my father had the same address as Hop Woo, the market gardening partnership he had with Lung Kie Chew in Riverdale.[8] By 1947 he gardened and lived in a house on the hillside near Government House where he befriended Ernest Stowe, the Chief Provincial Gardener. This friendship led to an advantageous arrangement to use city water for his garden.[9]

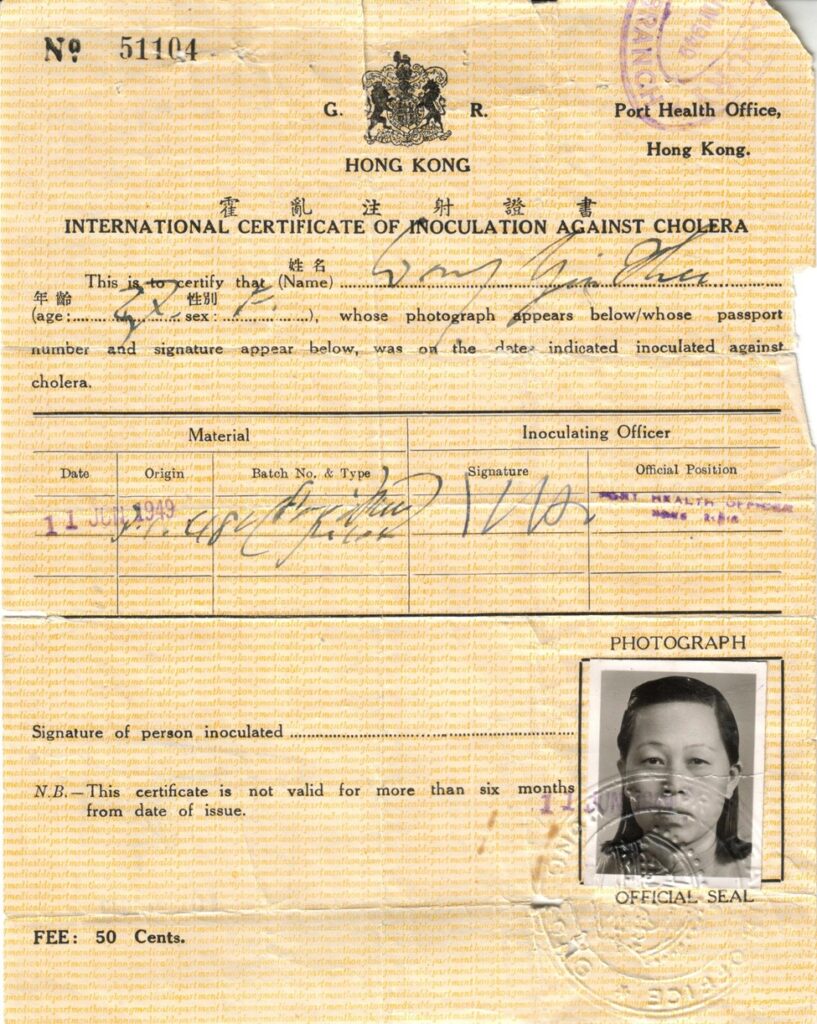

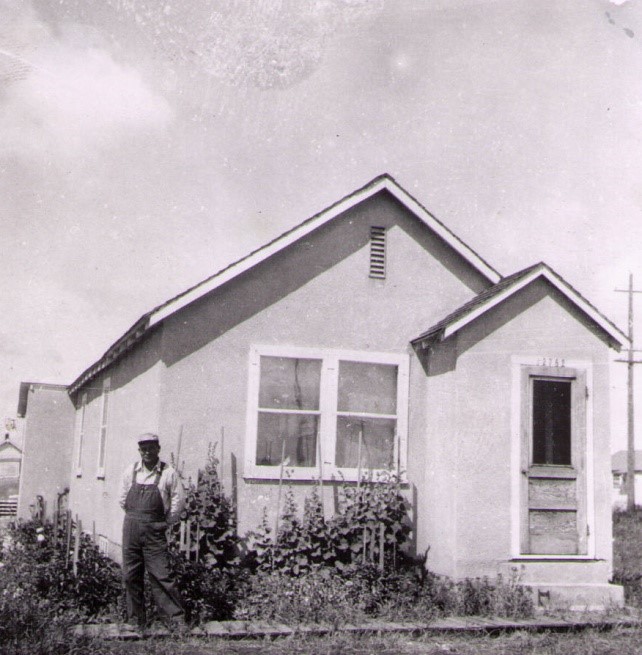

The discriminatory Chinese Exclusion Act was finally repealed on May 14, 1947 making it possible for Young See to join Bark Ging in 1949, eighteen and a half years after they were married.[10] Before her arrival, my father’s dwelling was moved to his 10-acre market garden in Calder. As Bark Ging’s solitary life came to a close, this was where he and Young See started their family.[11]

It was in 1954 that I came into this family and in 1956, with dreams of better prospects for his growing family, my father rented an additional 20 acres across the Clover Bar Bridge down on the river flats (at the bottom of present-day Sunridge Ski Area). We commuted from Calder through the old Town of Beverly and I was too young to contribute much but had the freedom to “help” scatter seeds like radishes and dig holes to plant squash seeds.

When spring planting was done, an array of irrigation pipes delivered water to our major crop of cabbages and other vegetables. My most vivid memory took place in early autumn. Our Chinese vegetables like bok choy and gai choy matured into tracts of bright yellow flowers. Dwarfed by the lofty stalks, it was an adventure to romp between the rows.

In 1958 we moved from Calder to Dovercourt commuting to our Beverly farm for another year or so. The gross income of $13,375.66 was the best year in our market gardening operations. The Calder market garden, locally known as Onion Park (named for our self-seeding onions) is now the Lauderdale Off-Leash Dog Park.[12]

The Calder house was moved again – this time to 10 acres of uncultivated land located north on Highway 28. This property became our Namao farm where I spent fifteen summers working alongside my family.[13] The land was in its natural state so we burned off the brush and the weeds. My father cut furrows the entire length of the farm using our Ford tractor with a two-bladed plow. After the exposed soil dried, a disc harrow was pulled to break down the clumps of soil. A wooden harrow was used to further break apart the soil to a finer texture before it was ready for sowing.

For the early crops of radishes we scattered seeds by hand. Vegetables with small seeds such as beets, carrots, dill, green onions, parsley and spinach, as well as Chinese vegetables like bok choy, suey choy, gai choy and gai lan were planted in rows using a push-seeder.

For days we planted acres of seedlings one by one in a grid about eighteen inches apart. One of us would use an empty tobacco tin on the end of a sturdy stick to deliver a dose of water to each plant.

On the hottest days we felt the heat of the earth burning our skin through our jeans. We scrambled to get the job done and hoped that rain would give the seedlings a chance at survival. After school and throughout the summers, we would eradicate weeds – a tedious undertaking using old rusty knives on our hands and knees. Many times, I raced my brother down the rows with two-wheeled hoes and inevitably scraped up a section of veggies, the unfortunate casualty of our races! Reprieve came when the weather was too wet to get on the fields – we rested at home.

Crops were ready for harvest in September and October. Typically, weekends were long working days especially Sundays as we processed large orders for delivery to wholesalers on Mondays.

The worst harvest I remember was after a light snowfall overnight with near freezing temperatures. Despite the inclement weather, it was urgent to fill the sales orders for cabbages. Dressed in layers, heavy coats, rain gear and rubber gloves, we found ourselves in the mucky field. The melting snow dripped off the ripe cabbage heads, pooling in the wrapper leaves near the ground. As the heads were cut, trimmed and dropped into wooden bushel baskets, we used the discarded leaves to form a pathway to keep the muck off our boots. As the weather worsened, we tried to work quickly but our hands went numb from the cold. It wasn’t long before I heard my father cussing a blue streak. He had sliced his hand badly. It looked terrible but he managed to wrap the wound with his handkerchief. There was no time to fuss so he just carried on.

Taking an entire day processing pounds of cabbages in rain or shine was exhausting. Each sack of cabbages was sewn up and then hefted onto the truck. I can still hear my father admonishing us, “Get an education so you don’t have to work like a mule.” We managed to scrape by a couple of lean years with net incomes of $587 in 1965 and $935 in 1971.

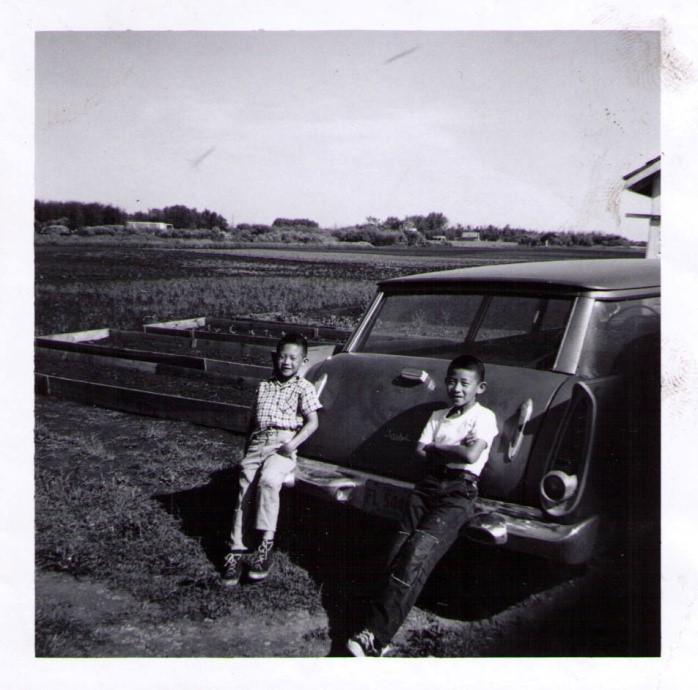

Across the road was the market garden of Gee Cheung (son of Gee Gut) who produced similar crops as ours. He had a son who would occasionally come over to play and we spent our time building a tree fort nestled in the southeast corner of the acreage, all while helping ourselves to wild Saskatoon berries growing nearby. We rode our bicycles to explore the rural roads and had the whole farm to practice driving after the crops were harvested.

In the off-season, my father never sought alternate employment. His source of entertainment was socializing and playing mah jong in the backrooms of merchant shops in Chinatown.

The Namao farm was finally sold on November 1, 1975 but true to form, my parents nurtured a backyard garden in their retirement.

Reflecting back, I heeded my father’s advice but I am still drawn back to his former market garden sites, half of which are still open to sun and sky, where I feel a special bond with the earth.

Ging Wei Wong © 2021

[1] The term Gold Mountain was used by the Chinese to refer to locations where gold was discovered in the 1800s. Specifically in the context of North America, it was the name used for California and British Columbia. Gold Mountain

[2] Between 1885 and 1923, more than 82,000 Chinese were forced to pay an exclusive, Chinese-only head tax. Starting with $50 in 1885, increasing to $100 in 1900, then $500 in 1903 the federal government collected more than $23 million that the Chinese could ill-afford.

The Chinese Head Tax and the Chinese Exclusion Act

https://humanrights.ca/story/the-chinese-head-tax-and-the-chinese-exclusion-act

[3] Wong Bark Ging was exempt from paying the $500 head tax in 1921

General Register of Chinese Immigration

Only merchants and their families, diplomats, tourists, students, clergy and men of science were exempt.

[4] A two-year limit on travel existed with strict adherence imposed by the federal government. Non-compliance resulted in being prohibited from returning to Canada.

Chinese Immigration Act

https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/chinese-immigration-act

[5] Barry Broadfoot, Ten Lost Years 1929-1939: Memories of Canadians Who Survived the Depression (McClelland & Stewart 1997)

[6] Chinese Market Gardens along North Saskatchewan

Kathryn Chase Merrett, Why Grow Here: Essays on Edmonton’s Gardening History (The University of Alberta Press 2015) pages 201-202. Henderson’s Directory: Hong Lee Co, market gardener, Groat Flats/Ravine 1922-1948; Gee Gut, market gardener, 9226-107 Street, 1937-1950

[7] Tony Cashman, High Level the Bridge That Refuses to Fall, Edmonton Journal. August 24, 2012

http://www.okthepk.ca/dataCprSiding/news/2012/2012082804.htm

[8] Hop Woo was the market gardening partnership Wong Bark Ging shared with Lung Kie Chew with the address 9013 – 101 Avenue (1939 Henderson Directories). It was dissolved in 1952.

Story by George Chew, son of Lung Kie Chew (George Sr.) Son of Riverdale’s market gardener looks back fondly, Riverdalian Newsletter, July 2012

[9] Bark Ging’s occupation was recorded as self-employed gardener on his Canadian Citizenship Application residing at the “rear of old Government House grounds.” August 18, 1947

Ernest Stowe helped my father to complete applications to bring Young See to Canada. Stowe retired and moved to the west coast in 1952.

[10] The Chinese Exclusion Act was responsible for keeping Wong Bark Ging and Young See apart for eighteen and a half years. She finally arrived in Canada on June 27, 1949.

[11] The Calder market garden was north of the CN railway tracks was bounded by 109 Street and 113 A Street, and 127 Avenue to 129 Avenue. The house address was 12782-113 Street.

[12] Naming Edmonton: From Ada to Zoie, The University of Alberta Press, 2004.

Market gardens fade into history, Letters, Edmonton Journal, November 23, 2008

[13] In 1959 located in the Municipal District of Sturgeon – Waldemere, (Plan 6215V, Lot 5 & 14, Blk 2) north on what was then the 2-lane Highway 28 (now 97 Street). The house was repurposed for storage. The land was later annexed by the City of Edmonton in 1971 and given the address of 9407 – 157 Avenue