Edmonton came by its reputation as a theatre city honestly, and more than once over the last century. At one time it boasted a plethora of dedicated performance halls and centres in the downtown core. One of these Edmonton jewels had roots in the Klondike Gold Rush thanks to a figure named Alexander Pantages.

Pantages made his way to Dawson City to find his fortune. Like so many others, he arrived in the aftermath, just in time to see the gold fever fade. But he did manage to find a way to find good fortune by making the acquaintance of Kathleen Rockwell, also known as Klondike Kate, a burlesque dancer who had also headed north seeking her own brand of luck.

They became an unmarried power couple in Dawson City, and with money he borrowed from her, he built his first theatre: The Orpheum, which raked in an astonishing $8,000 a day at its peak, largely from the throngs of miners that came to witness The Yukon Flame – a burlesque dance Kate had created that used hundreds of yards of bright red fabric to provocatively reveal just enough to drive audiences into a frenzy.

When Alexander married the secretary he had been secretly seeing when Kate wasn’t around, the partnership ended, along with the Gold Rush, and they both ended up back in the U.S. Alexander went to Seattle, and Kate toured her act. Pantages cashed in on his reputation as a builder of successful touring houses and began to build theatres. He commissioned the young architect B. Marcus Priteca, a Seattle resident who would have a long and lucrative association designing many Pantages theatres, eventually bringing 22 of the grand spaces to life – the largest chain of theatres in North America. He designed his first Pantages Theatre in San Francisco, followed by two Seattle theatres. A fourth followed in 1908 in Vancouver.

Pantages wanted to expand east, having figured out how to program live acts that would tour the west coast. He needed a prairie outpost to bridge the long gap between Vancouver and Winnipeg so he set his sights on the wilds of Edmonton.

Pantages entered into conversations with George Brown, an Edmonton businessman who would lend his name to the structure. From Seattle, Pantages shrewdly refused to foot the entire bill for the new Brown Block, which would house the theatre and tower, and so Brown worked to convince City Council to loan the project $50,000.

The building and theatre had two different architects – the understated two-story brick frontage (The Brown Block) was created by Edmonton architect Edward Collis Hopkins, whereas the actual theatre was designed by Priteca. In March of 1912, the newspapers in Edmonton announced a 10-storey building. By June, it was more conservatively planned at 5 stories. However, they went ahead and built foundations that would support a 15-storey structure.

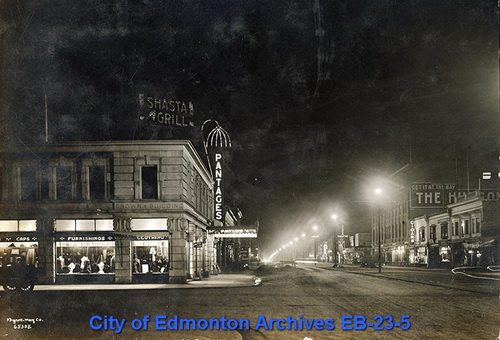

It was all semantics anyway, as the additional stories were never built. What was built was phase one of an ambitious 10-story skyscraper on the corner of Jasper Avenue and 102 street, in the heart of downtown. The main building – the two stories that would have acted as the base of the tower – faced Jasper Avenue, and the theatre loomed large behind it.

Brown Building & Brown Confectionery. Image courtesy of the City of Edmonton Archives, EA-10-370

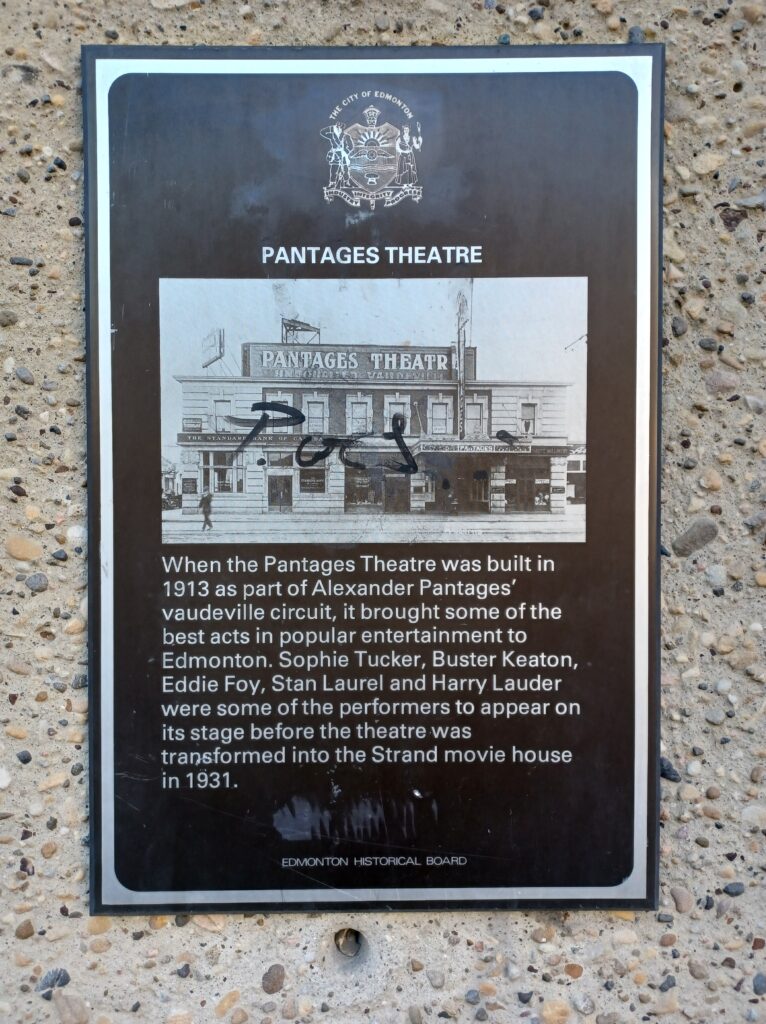

The purpose was live entertainment, as boldly declared on the wall facing Jasper Avenue: “PANTAGES: Unequalled Vaudeville” was painted in huge letters on the side of the building.

The northeast corner featured what would become another institution: Edmonton’s first cafeteria, the American Dairy Lunch, which operated until 1955, when it became Ciro’s.

It was May of 1913 when the Pantages opened. Thousands rushed through the main entrance – albeit an hour later than the advertised launch – so many people, in fact, that the doorman, Charles Wilson, couldn’t verify who had tickets and who didn’t. It was his first night on the job – a duty he would perform for decades, through the building’s many incarnations.

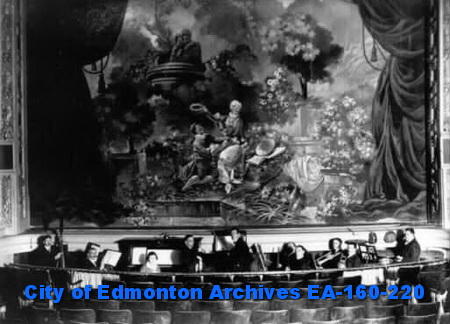

What the opening night audience saw that night was a spectacular sight. Priteca had created a Neo-Greek fantasia, seating 1600 patrons. Lush and ornate, the theatre featured imported Italian and Grecian marble, Chinese silk wall panels, handprinted murals, and heavy draperies trimmed in elaborate hand-embroidery. The Edmonton Bulletin referred to it as “the handsomest theatre in Western Canada”. Going a step further, the Edmonton Journal called it “The most Northerly High Class Vaudeville Playhouse in North America”.

Over the next decade, the Pantages hosted the brightest lights of the vaudeville circuit as they made their way around this western performing tour – The Marx Brothers, Sophie Tucker, Will Rogers, Buster Keaton, Eddy Foy, a pre-Hardy Stan Laurel and Harry Lauder. Joy Yule brought his newborn son into the stage, marking the debut of the star who would eventually be Mickey Rooney.

But there was already a seismic cultural shift in the making. The new film industry was forcing the Vaudeville circuit to adapt.

There came the day when all the old performing theatres and road-houses, lacking enough touring entertainers as well as responding to the growing numbers of cinema fans, began the inevitable transition to becoming movie houses. Fortunes were shifting in the show business world. Eventually, The Pantages was the only theatre in Edmonton that was still offering Vaudeville, as the rest of the entertainment houses had installed screens and changed their names. For a time, films and live performers shared the same bill, but eventually the cost of touring live performers to audiences that preferred to be dazzled by this new medium was too prohibitive.

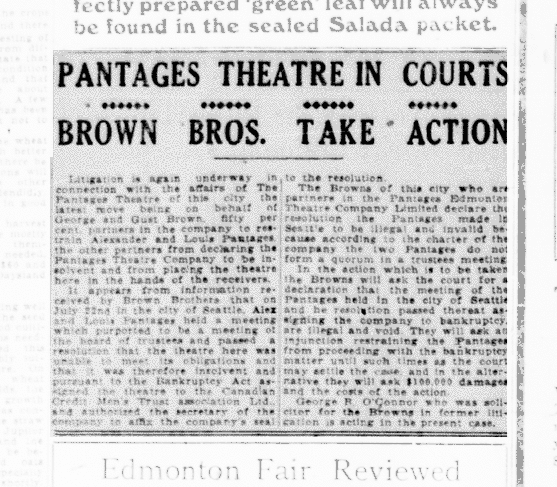

In 1921, there were disagreements between Brown and Pantages. There was no programming at all on the Pantages stage in July of that year. From San Fransisco, Pantages offered this shrewd advice: declare bankruptcy. To drive the point home he pulled his touring circuit, severing his ties with Edmonton and deleting the city as a stop on his national touring circuit, cutting off the lifeblood of the entertainment houses across the country. It only took Brown a few months to make the transition to a movie house permanent, and the mighty Pantages Theatre finally closed, only to reopen as The Metropolitan, showing movies on the giant stage in between the few remaining live touring acts.

The stock market crash of 1929-30 hastened the demise of the Vaudeville roadshows, halting touring altogether, shattering “The Road” permanently. But this allowed community theatre to get a foothold. Edmonton Little Theatre launched in 1929 in this new void of live performance, with a mandate to nurture local theatrical talents. Edmonton’s second life as a theatre town was born.

At the beginning of the depression The Metropolitan actually closed completely, but then in 1931, it was purchased by Alex Entwhistle and updated for sound movies. It reopened and was renamed again as The Strand Cinema, part of a national chain of movie houses. But the theatre was still being utilized in other ways as well, providing a prominent and stately gathering space. The stage was shared by arts organizations like Empire Opera Company and Civic Opera Company, becoming more essential to the downtown performing arts community.

The upstairs offices of the prominent corner building were filled with local businesses like lawyers and dentists, and one small apartment housed the small family of doorman Charles Wilson. But these rooms also contained the rehearsal spaces where theatre could be created, and where acting could be taught. In 1931, Edmonton Little Theatre held its first drama class in one of those upstairs offices, and on May 1st of that year, its first production opened on the Strand stage: “Liliom” by Ferenc Molnar, directed by a woman who would leave an indelible impression on Edmonton’s theatre history: Elizabeth Sterling Haynes

The wider arts community seized the opportunity to use the stage, and soon it was also a place to see a production by the new Opera Company: Empire Opera, led by virtuoso conducting prodigy, Atha Andrewe.

Edmonton Little Theatre began to produce a regular season with several plays a year, often featuring Edmonton artists and playwrights such as Elsie Park Gowan, and Harvey Kagna. The community was very interconnected – Kagna was not only a playwright and personal friend of Elizabeth Haynes, but he was President of the board of Edmonton Little Theatre. He also knew enough about stage makeup to work backstage in the dressing rooms of the Strand when the large opera productions were presented on the stage. His family also owned a prominent downtown bakery, and had a very respected reputation in Edmonton’s Jewish community.

In 1935, when Alberta elected Bill Aberhart as Premier, it was heading into a new era that would define it as a province. Aberhart attempted to steer the province into a sort of prairie theocracy. From 1936-1940, Bible Bill tore up the airwaves in broadcasts from the stage of The Strand in full-throttle fire and brimstone prophesies that were broadcast province-wide and beyond. In front of a live audience, he would rail against the evils of modern society. Topics included the war, “the Jews”, and Alberta’s role in confederation.

In 1942, a scandal rocked the Edmonton arts community, and became the talk of the city for an entire summer and beyond. The President of the Board of the Edmonton Little Theatre company, Harvey Kagna, was charged with over a dozen accounts of “gross indecency”, a charge that could mean almost anything the prosecutor wanted, but in this case was used to refer to Kagna’s sexual relations with other men, many of them in the arts community. Also swept up in the turbulence were actor/playwright Jimmy Richardson, as well as the artistic director and conductor of the Empire Opera Company, Atha Andrewe. The resultant media frenzy and judicial overreach resulted in dozens of charges for over a dozen men. By the time the dust settled, several men had their lives and reputations destroyed, Empire Opera Company cancelled its upcoming production and folded altogether shortly after, and in fact the theatre community took decades to recover from the polarized divide that its members experienced as their artistic peers were sentenced to hard labour.

“Strand Theatre, Edmonton, Alberta.”, (CU165050) by . Courtesy of Libraries and Cultural Resources Digital Collections, University of Calgary

The arts community was shaken, and not long after, Edmonton Little Theatre folded, and a new company was born. Naturally it presented work on the stage of The Strand, which remained a mainstay of the performing community, even after the scandal.

Theatre pioneer Margaret Mooney remembers studying acting with theatre legend Elizabeth Sterling Haynes in the offices of the second floor of the Strand from 1949 to 1955. She also recalls being con-signed to construct and gather props for the very first Walterdale Melodrama, “Tempted, Tried & True”, which was presented on the stage of the Strand in 1965.

The theatre was renovated in 1953, and in 1956, was purchased by the Famous Players chain. Then it was purchased in 1959 by First Northern Building Corporation.

It’s impossible to say when it began to be known as a place for gay men to connect, but in the pre-gay-bar years when downtown was full of discrete places for LGBTQ people to meet, one of the locations where gay men could find each other was in the flickering half-light of second-run movies that showed at The Strand. Even as late as 1971, The Strand still had a reputation in the gay cruising community as a place to connect- specifically in the notorious back row. It was com-mon enough knowledge within the local gay community that in the infamous “Guide for the Naive Homosexual” – a never-published but much-shared volume describing gay life in Canada written by early GATE founder Roedy Green that discretely made the rounds in the late 60’s – early 70s, The Strand Theatre is listed in the Edmonton cruising listings with the frank description “a lively back row, but is definitely not recommended except for the most brazen and desperate of people.”

In 1976, the fading theatre was declared a Provincial Historic Resource and on December 30, 1978, the final showing of Elliot Gould in The Silent Partner was the last piece of art on the 56-year-old stage. Despite receiving a distinction as a landmark of historic signifi-cance, it was demolished to make way for the IPL tower, now named Enbridge.

A replica of the neon sign from the original Pantages Theatre is on display at the neon sign museum on 104 street in downtown Edmonton.

©Darrin Hagen