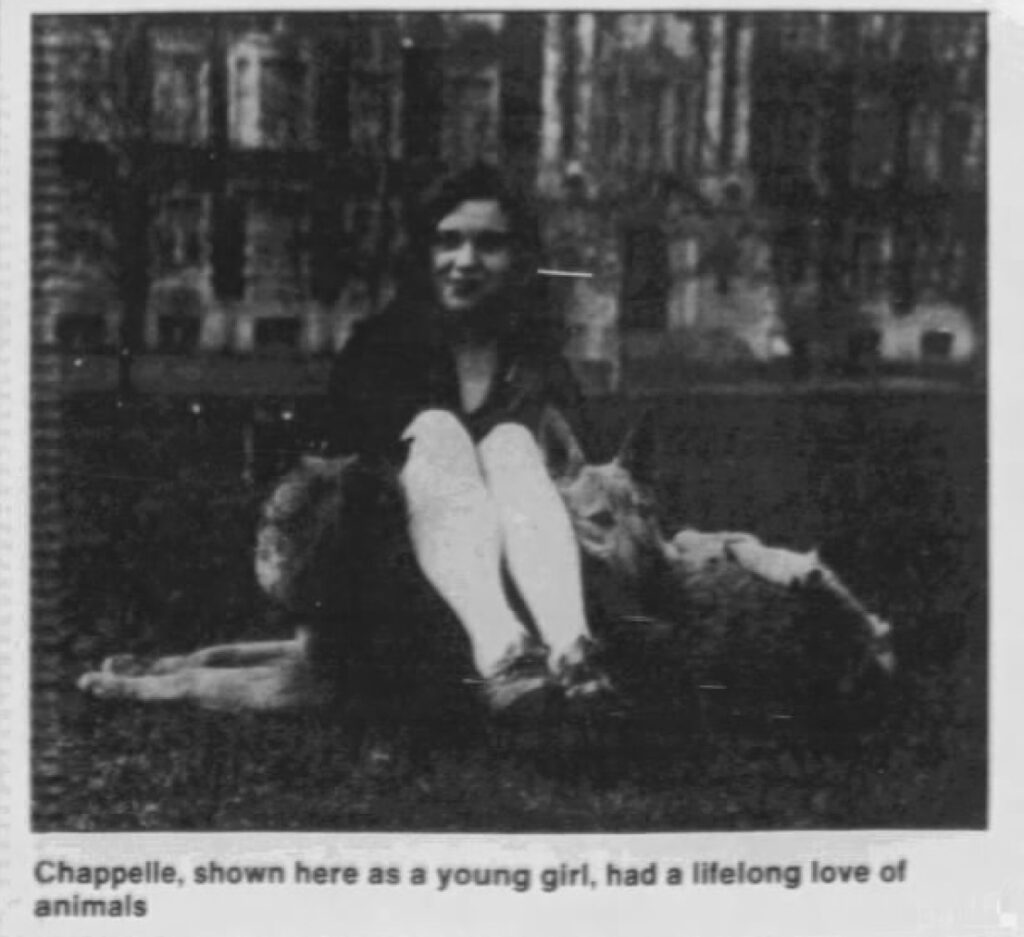

Margaret Chappelle was an unlikely activist: the only child of wealthy parents, and wife to a successful young doctor, she never wanted for anything, even in the lean years of the Great Depression. Throughout her childhood and adolescence, she was free to explore her twin passions for art and nature without having to worry about work or money.[1]

“To us, she had it all,” her friend Dorothy Barnhouse recalled. “A rich family, elegant clothes and lots of talent. She got the lead role in all the plays and had this handsome older doctor as a boyfriend. It was the height of the Depression and he’d pick her up in his big black Buick – well, all the girls just had their tongues hanging out drooling when they saw them together.”[2]

But even in these early years, Margaret showed the sparks of defiance that would eventually lead her to organize one of Edmonton’s most iconic environmental campaigns and (allegedly) lie down in front of a bulldozer. Her parents were extremely religious and came from a church that rejected modern medicine, and they opposed her marriage to a man who was not only a doctor but also 11 years her senior. But Margaret stood firm in her convictions, even if they caused a years-long rift between her and her family. “She lived the way she wanted and didn’t care what anyone thought or said about her,” said friend Yvette Morin.[3]

When she was 32, Margaret decided to study fine art at the University of Alberta. She developed a career as an accomplished artist, both in Alberta and internationally. She served as the president of the Edmonton Art Club and the Federation of Canadian Artists, and served on the board of the Edmonton Art Gallery.[4] She won the medal of honour for ceramics at the International Exposition of Contemporary Ceramics in Prague[5] and had ceramics displayed at the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, D.C.[6] She painted in a variety of media—watercolours, acrylics, and oils—and covered a wide array of subjects in her paintings—from Edmonton urban landscapes to studies of flowers and even reclining nudes.[7] She was particularly influenced by the Group of Seven’s methods, and did field sketches out in nature.[8] Her love and respect for Canada’s natural beauty is reflected in most of her canvasses, which show scenes of the Rocky Mountains, Elk Island Park, and her own backyard in Edmonton.

Margaret and her husband shared a deep love. They had no children and built a happy and comfortable life full of passions and hobbies, good friends, and beloved pets.[9] They may have stayed that way for the rest of their lives, leaving behind a legacy of paintings and philanthropy. But when the beauty of the natural landscape met the relentless grind of urban progress in Margaret’s own backyard, she rose to meet the moment—launching into an 18-year-long battle to protect MacKinnon Ravine, and Edmonton’s river valley more broadly.

“Margaret Chappelle hadn’t expected to find herself spearheading a civic dispute,” wrote the Edmonton Journal. “It wasn’t in her books to become a crusader, to picket, to petition City Hall, to attend council meetings, make speeches. She hadn’t expected to apply herself to the study of city bylaws, become absorbed in city engineering or finance until investment loomed to construct what she terms ‘cement canyons’. For she has always seen the magnificent valley and its deep ravines cleaving the high banks as Edmonton’s unique beauty.”[10]

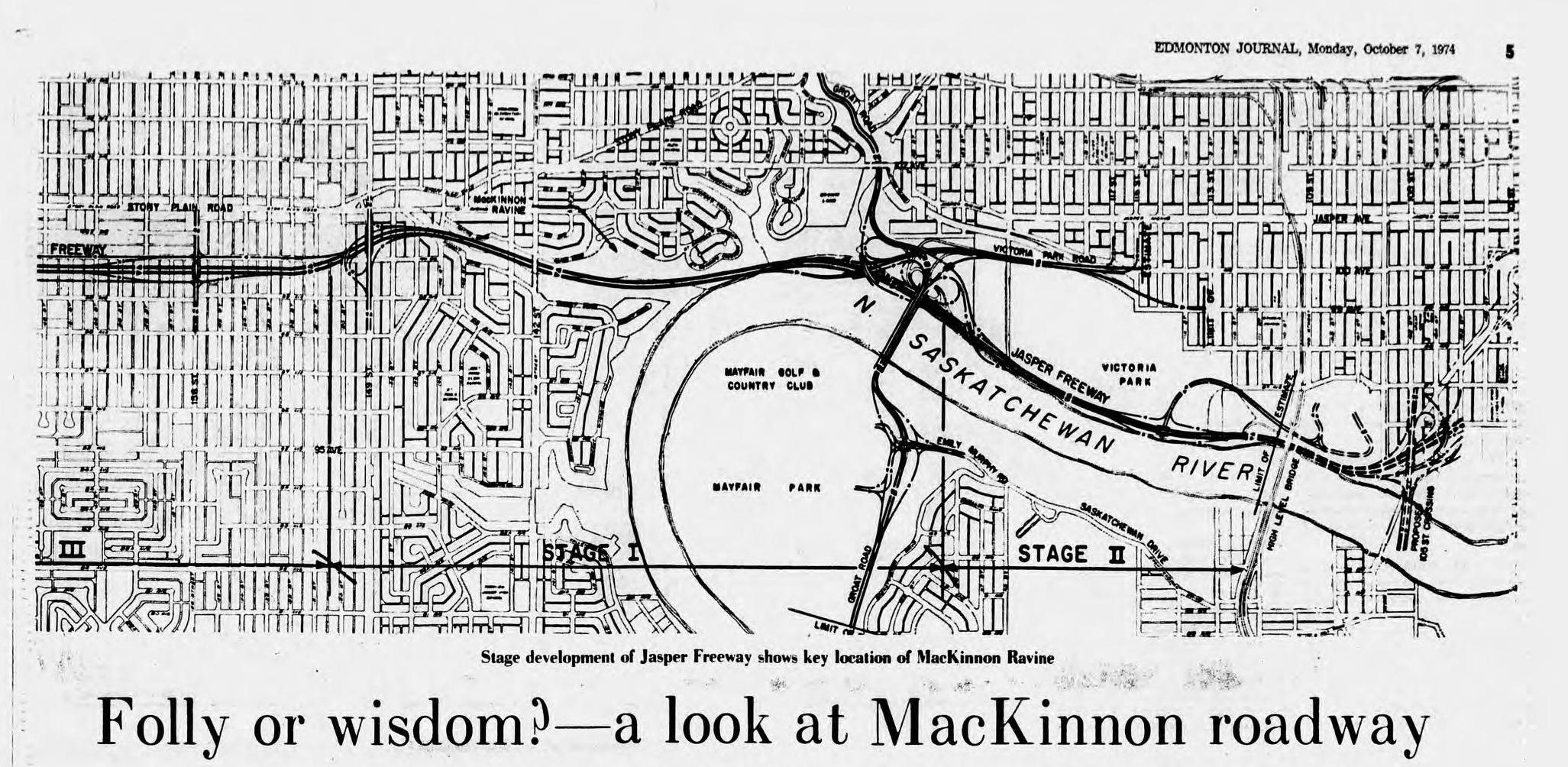

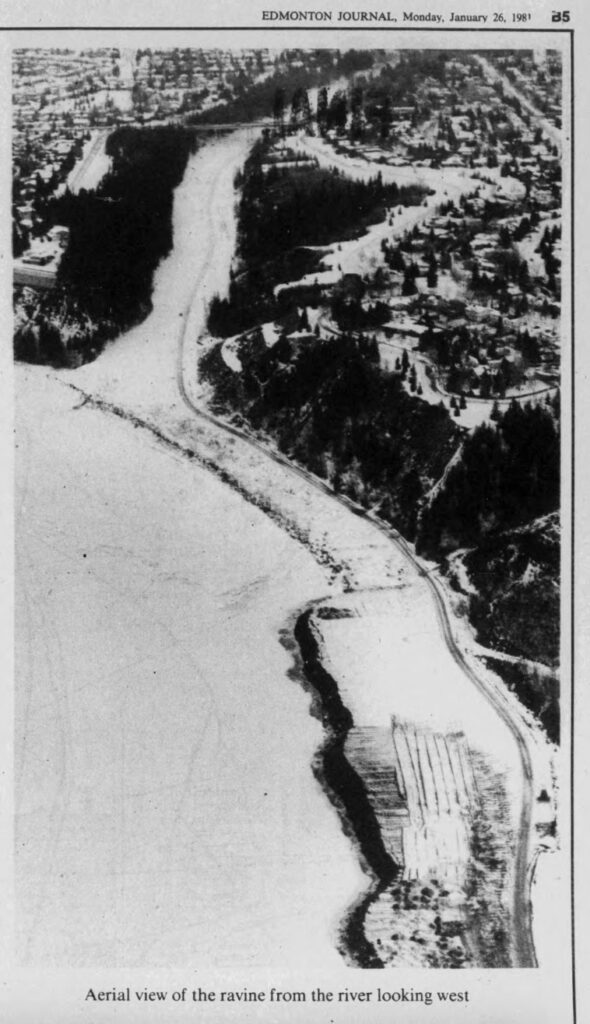

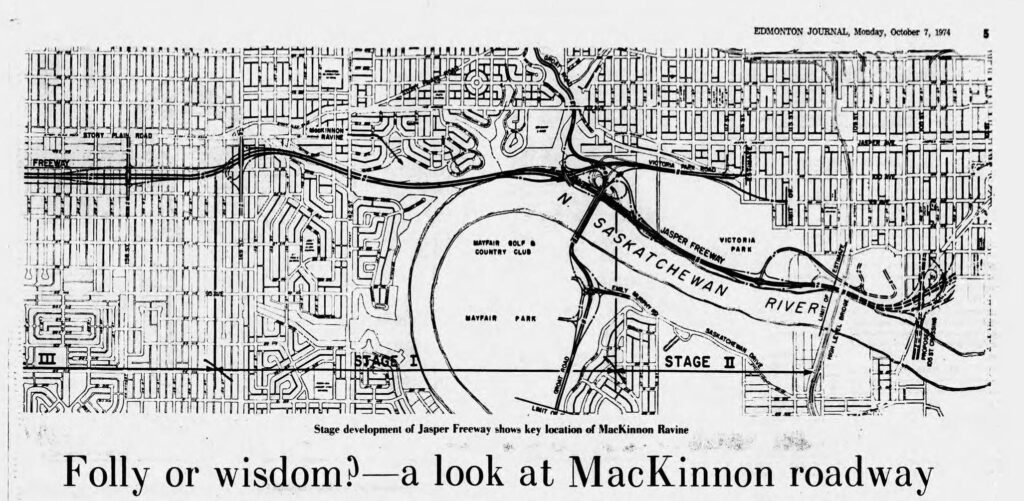

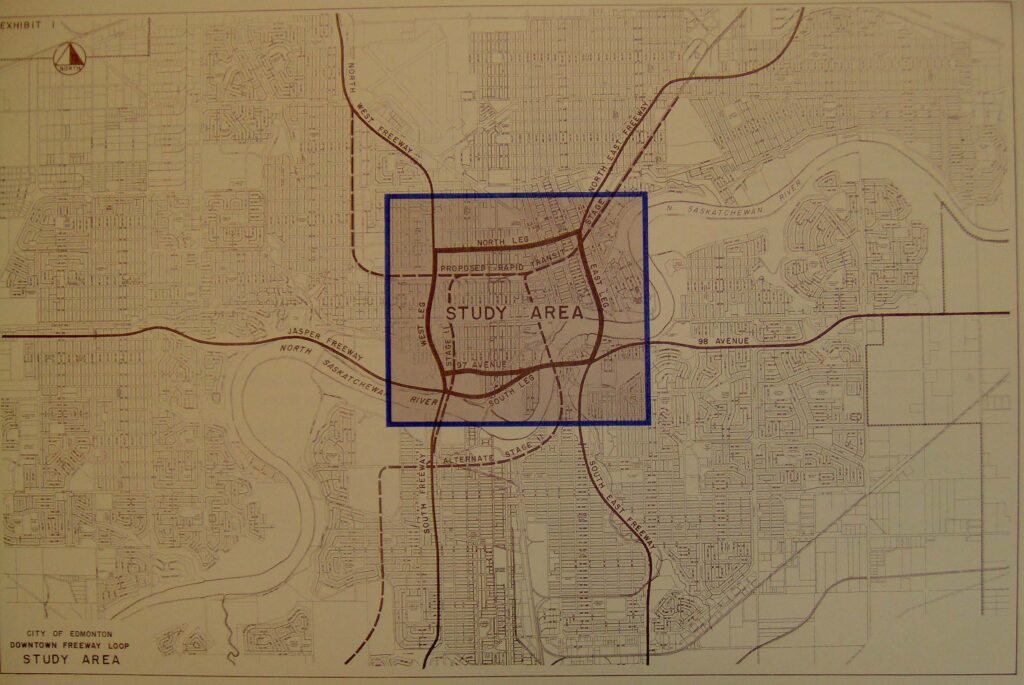

Let’s pull back for a second and look at Edmonton in the mid-1960s. The city was booming, its population growing rapidly every year, and traffic congestion was a real problem. The Metropolitan Edmonton Transportation Study was a proposal launched in 1964 to solve all these problems by building a series of massive freeways feeding into downtown—including plowing roads through five river-valley ravines, Mill Creek and MacKinnon Ravine among them.[11] It was estimated that METS “would destroy 11 per cent of the river valley.”[12]

The Mill Creek proposal was immediately controversial and just as immediately, shelved.[13] But the MacKinnon Ravine proposal was allowed to continue, and the METS plan was approved by city council in December 1964,[14] raising the prospect of a six-lane highway running directly behind Margaret Chappelle’s house.

On 7 January 1965, Margaret Chappelle issued a declaration in opposition to the project, bringing her distinct perspective as an artist to the environmental fight. “We have no right to destroy this beauty,” was the headline of her article in the Edmonton Journal’s Dissent section.[15] “I am among many who disagree with what has been done, is being done, and will be done in the future to destroy the beauty of this city,” she wrote. “Is Edmonton different from other cities? Yes! Because of a few God-given assets—our lovely river valley, the well-treed ravines. Without these we would have another flat, windy uninteresting city. Now these things stand in danger of being taken from us.”[16]

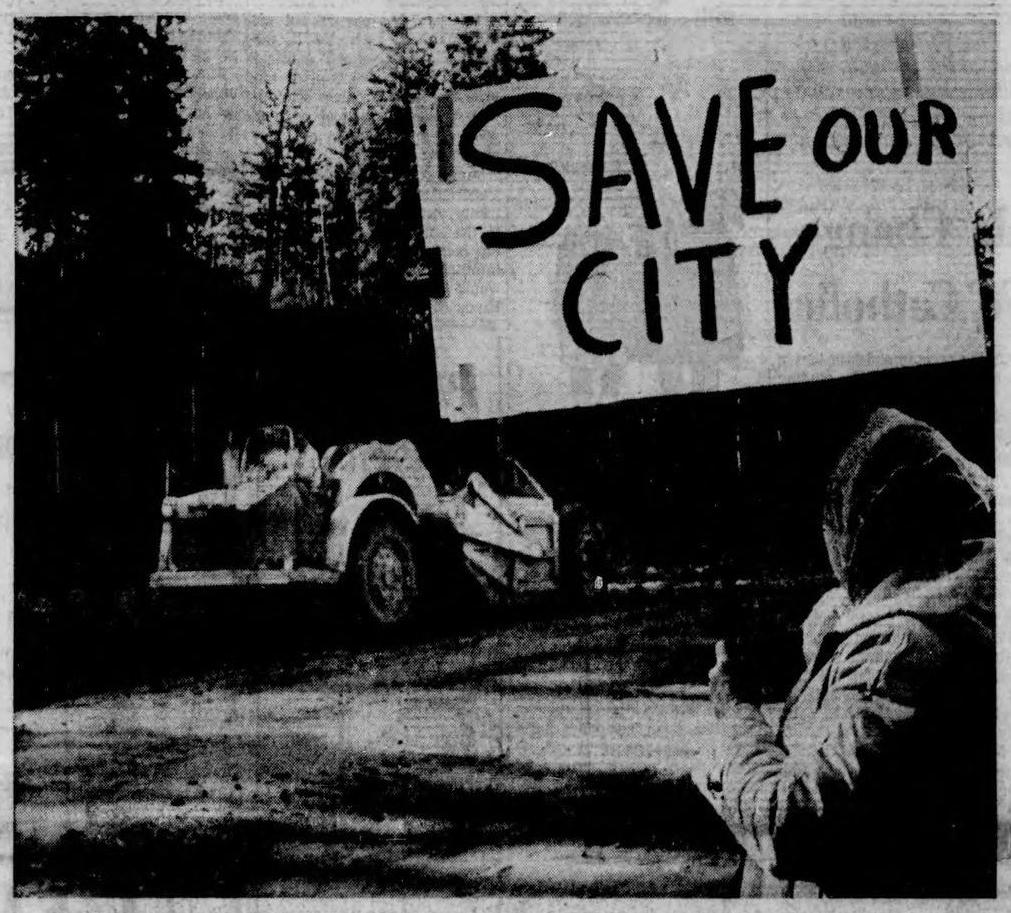

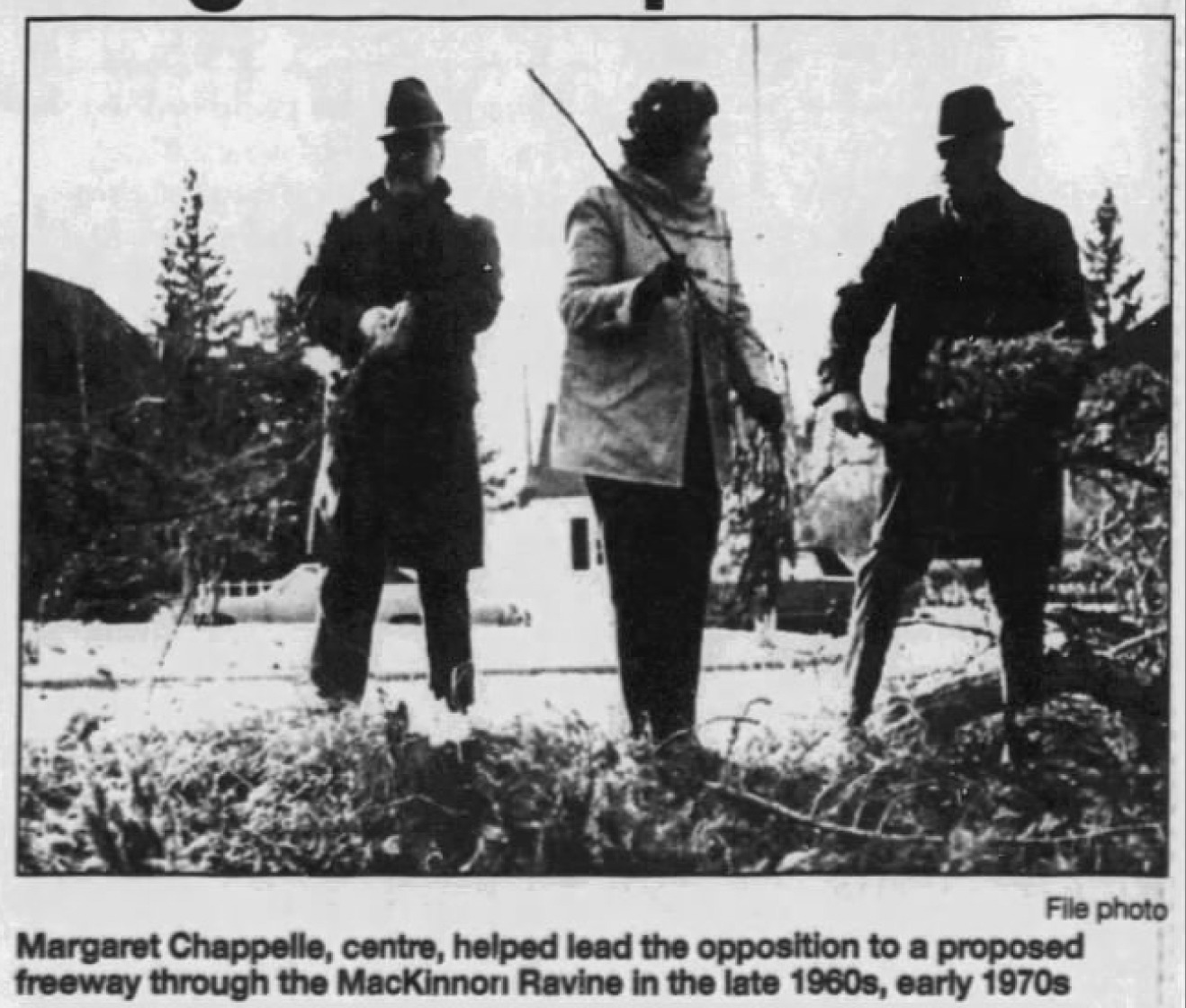

Despite support for this position by some city councillors, the parks department, and her fellow citizens,[17] the city started survey work and grade improvement on the MacKinnon Ravine freeway in May 1965.[18] So Margaret helped organize the Save Our Parks Association to resist the project. At first, they issued statements and petitioned the city administration.[19] But when work continued, and city contractors started cutting down large trees—some of which were over 200 years old—Margaret and her compatriots decided to take direct action.[20]

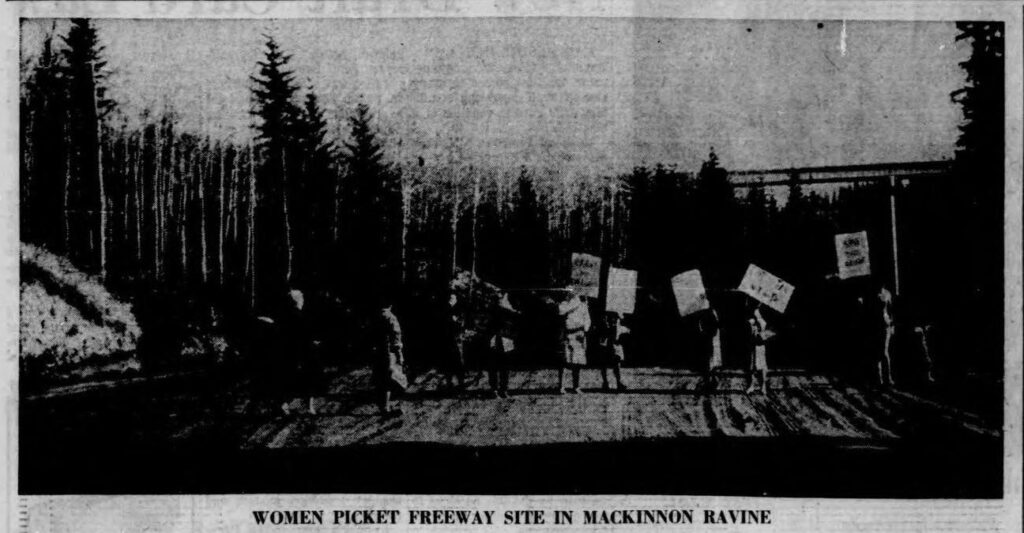

“West Edmonton’s women are on the warpath,” declared the Journal, revealing the gendered dynamic of the fight. As Margaret and other women marched with signs declaring “Treeways—not freeways” and vowed to sit in the trees and block the roads if the clearcutting continued, “city truck drivers drew the wrath of the women as they laughed at the pickets when they drove across the bridge with a truck load of logs from the ravine.”[21] The Save Our Parks Association decided to warn residents in other areas where work was planned, like the Quesnell ravine. “They’ll wreck the other ravines over my dead body,” said Margaret.[22]

When work continued unabated a week later, Margaret and seven other women walked down onto the freeway road bed—only to watch the equipment operators drive their machines away and wait until the protestors left before resuming work. “They (the city) are out of their minds doing this,” said fellow protestor Maria Jablonski. “It’s the old colonial spirit – just exploit for material convenience with no regard for what comes afterward.”[23]

Margaret and her crew continued their protest (“The ladies are at it again,” wrote the Journal), receiving calls and letters of support from across the city and around the province.[24] They took the fight to City Hall, protesting outside the council chambers and issuing a declaration stating that “the invasion of the ravines, the death of trees and wild life are acts of degrading violence… Only by the public showing open rebellion can we make the city administration realize its extravagant folly.”[25]

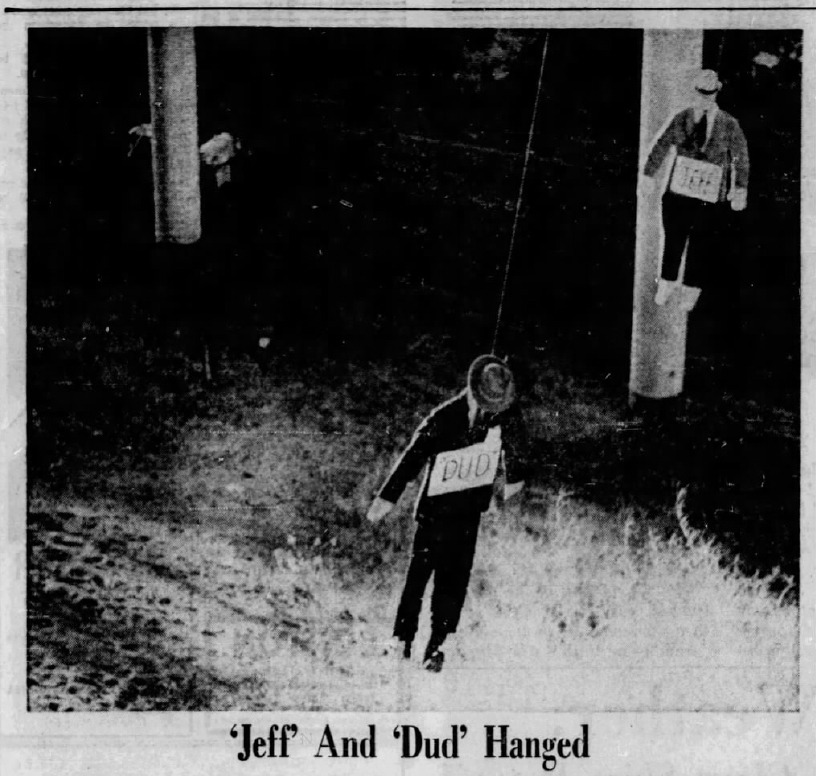

Save Our Parks was also supported by more active measures than just phone calls and letters. Neighbourhood “youngsters” shot at trucks with BB guns and pulled up survey stakes.[26] Effigies marked with the names “Jeff” and “Dud” and labelled “Vandals of the Year”—which were assumed to represent two city commissioners involved in the project—were hung from the 142nd street bridge.[27] Margaret disclaimed Save Our Parks’ involvement in the effigies, but they showed the intensity with which area residents were greeting the freeway development.

The battle stretched on in fits and starts over the years, and Margaret expanded her knowledge and focus from just MacKinnon Ravine to the entire city. In 1967, she called out the city’s dishonesty on their stated policy that new acres of parkland would be taken on for every acre lost to commercial development, noting that some of the additional acres counted as “parkland” were actually cemeteries and even a city dump.[28]

In 1972, the city unexpectedly resumed construction of the MacKinnon Ravine freeway, cutting down trees without notifying area residents first.[29] Margaret and Save Our Parks quickly reactivated their campaign[30] and managed to get construction halted until a long-range city transportation plan could be adopted by council.[31] City councillors continued to haggle back-and-forth about the freeway throughout the 1970s,[32] and city administration produced reports both in favour[33] and opposed to[34] the project. In 1981, city council order a public plebiscite on the issue[35] and then scrapped the vote.[36]

Margaret followed the issue closely through all the turbulent years, ready to spring back into action if needed. “The war is still on and I’ve really enjoyed the scrap,” she told a reporter. “It’s a fight well worth fighting.”[37] By then Margaret had developed a well-earned reputation as an unmovable defender of the ravine and the river valley, which over the years grew into the legend of Margaret and the bulldozer. Reports vary of what actually occurred. In some versions, Margaret and her fellow protestors were just “threatening to lie down in front of the bulldozer,”[38] in others she “stood in front of bulldozers.”[39] One friend had a more specific memory of Margaret “pushing a baby carriage in front of the bulldozers and then lying down in front of one.”[40] One historical account went so far as to describe Margaret “flinging her body in front of a bulldozer”[41] to stop the roadway construction. What is clear is that Margaret didn’t shy away from the fight—and in the end, she won.

In December 1983, city council threw out the river valley policy that allowed the development of major roadways or utilities in the valley.[42] This effectively ended the freeway, and the next summer hundreds of people celebrated the opening of the MacKinnon Ravine Park with ice cream, hot air balloon rides, and “I love MacKinnon Ravine” buttons.[43] The freeway proposal resurfaced again and again over the following years, but by the end of the 1980s the facts on the ground were clear—the ravine was officially a park, with grass and bike trails and picnic sites.[44]

Following her victory, Margaret spent the last decade of her life in relative seclusion, especially after her husband’s death.[45] She took in stray cats and took on a reputation as a “crazy cat lady”[46] whose cats “ate like kings and were just spoiled rotten.”[47] She continued to paint, sketching in her secluded backyard beside the ravine.[48] She lived a frugal life, saving up her considerable wealth for one last act of civic charity.

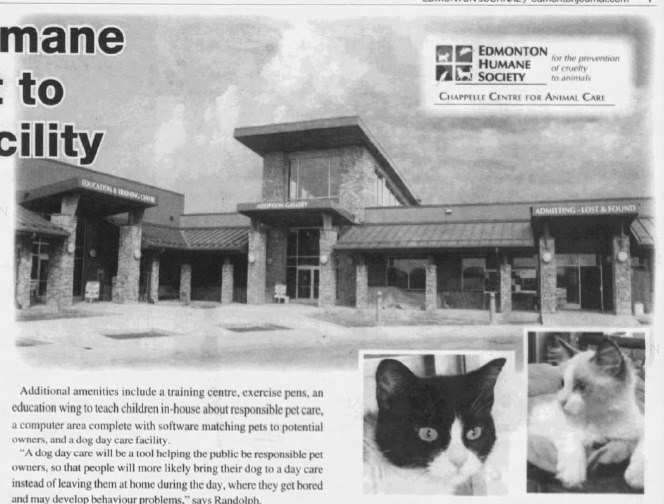

“In the end,” said the Journal in the first line of her obituary, “Margaret Chappelle had only her cats, her art and $3.7 million.”[49] With no next-of-kin and no will on record, this sensational sum went unclaimed for weeks. But eventually a hand-written will was found under a pile of boxes in her garage, and it turned out that Margaret had donated almost all of her vast fortune to the Edmonton SPCA.[50]

Margaret Chappelle’s legacy extends far beyond this incredible donation, or even the long battle to save the ravine. Her fight was for beauty, for life, for all of Edmonton’s natural spaces, which are threatened over and over again. Her words ring as true today as they did in that first full-throated declaration, urging us to defend the river valley and its ravines, Edmonton’s crown jewels.

“To keep our parkland will require a watchdog attitude and a crusading spirit of all Edmontonians,” she said.[51] “No amount of money is large enough to buy back any ravine… What are we building, a city to accommodate more and faster machines? Or to accommodate more and better people? Let us take the firm stand—our parklands are inviolate.”[52]

Paintings:

Rocky Mountains: https://hermis.alberta.ca/afa/Details.aspx?ObjectID=GHF92.004.001&dv=True

Jasper Avenue cityscape: https://hermis.alberta.ca/afa/Details.aspx?ObjectID=2006.017.001&dv=True

Elk Island: https://hermis.alberta.ca/afa/Details.aspx?ObjectID=1998.002.001&dv=True

Margaret’s backyard: https://hermis.alberta.ca/afa/Details.aspx?ObjectID=2006.029.001&dv=True

METS plans:

http://albertaroads.homestead.com/edmonton/METS/ultimatestagekey.jpg

http://albertaroads.homestead.com/edmonton/METS/overview.jpg (note the “Jasper Freeway” going up through MacKinnon Ravine to the west of downtown Edmonton)

[1] “Coming from a well-off family and later married to a successful doctor, Chappelle had the resources and the leisure to pursue her artistic interests.” – “Chappelle, Margaret.” Alberta Heritage Resources Management Information System (HeRMIS), Provincial Art Collection. Accessed 20 August 2021. https://hermis.alberta.ca/afa/Details.aspx?ObjectID=2006.017.001&dv=True

[2] “A Reclusive Activist – Artist’s legacy goes far beyond $3.7M gift to SPCA.” Stephen Erwin. Edmonton Journal, 24 January 1993, page 11.

[3] “A Reclusive Activist – Artist’s legacy goes far beyond $3.7M gift to SPCA.” Stephen Erwin. Edmonton Journal, 24 January 1993, page 11.

[4] “Chappelle, Margaret.” Alberta Heritage Resources Management Information System (HeRMIS), Provincial Art Collection. Accessed 20 August 2021. https://hermis.alberta.ca/afa/Details.aspx?ObjectID=2006.017.001&dv=True

[5] “Chappelle, Margaret.” City of Edmonton Archives. Accessed 20 August 2021. https://cityarchives.edmonton.ca/chappelle-margaret

[6] “Gallery Opened For Modern Works.” Edmonton Journal, 25 November 1961, page 20.

[7] “Will stipulated that works should be held for 10 years before being seen again.” Edmonton Journal, 14 November 2003, page 31.

[8] “Will stipulated that works should be held for 10 years before being seen again.” Edmonton Journal, 14 November 2003, page 31.

[9] “A Reclusive Activist – Artist’s legacy goes far beyond $3.7M gift to SPCA.” Stephen Erwin. Edmonton Journal, 24 January 1993, page 11.

[10] “Artist With A Cause.” Ruth Bowen. Edmonton Journal, 15 February 1966, page 15.

[11] “Parks Program Urged After METS Proposal.” Edmonton Journal, 17 June 1964, page 3.

[12] “MacKinnon – A solution appears to be near in the debate that has raged 17 years.” Robin Barstow. Edmonton Journal, 26 January 1981, page 21.

[13] “City Shelves Freeway Plan.” Edmonton Journal, 17 June 1964, page 3.

[14] “MacKinnon – A solution appears to be near in the debate that has raged 17 years.” Robin Barstow. Edmonton Journal, 26 January 1981, page 21.

[15] “We have no right to destroy this beauty.” Margaret Chappelle. Edmonton Journal, 7 January 1965, page 6.

[16] “We have no right to destroy this beauty.” Margaret Chappelle. Edmonton Journal, 7 January 1965, page 6.

[17] “Save Ravines – Letters to the Editor.” Peggy Marshall. Edmonton Journal, 12 February 1965, page 42.

[18] “MacKinnon – A solution appears to be near in the debate that has raged 17 years.” Robin Barstow. Edmonton Journal, 26 January 1981, page 21.

[19] “Saving Parkland.” Margaret Chappelle, Letter to the Editor. Edmonton Journal, 24 March 1965, page 15.

[20] “Keep Out Of Ravine Or Else—Women Warn.” Edmonton Journal, 12 October 1965, page 3.

[21] “Keep Out Of Ravine Or Else—Women Warn.” Edmonton Journal, 12 October 1965, page 3.

[22] “Keep Out Of Ravine Or Else—Women Warn.” Edmonton Journal, 12 October 1965, page 3.

[23] “They Halt Work.” Edmonton Journal, 18 October 1965, page 1.

[24] “Freeway Protest Rolls On.” Edmonton Journal, 22 October 1965, page 3.

[25] “Women Protest Parkland Loss At City Hall.” Edmonton Journal, 26 October 1965, page 25.

[26] “Keep Out Of Ravine Or Else—Women Warn.” Edmonton Journal, 12 October 1965, page 3.

[27] “‘Jeff’ And ‘Dud’ Hanged.” Edmonton Journal, 30 October 1965, page 1.

[28] “Edmonton needs a firm parks policy – They’ve nibbled away nearly 700 acres, charges Margaret Chappelle.” Margaret Chappelle. Edmonton Journal, 18 July 1967, page 5.

[29] “Jasper freeway could be open by year end.” Andy Olge. Edmonton Journal, 29 March 1972, page 57. – “The city quietly sneaked in with axes and began cutting down trees before we were aware of what was going on.”

[30] “Campaign Started to Halt Freeway.” Edmonton Journal, 5 April 1972, page 68.

[31] “‘No alternatives to MacKinnon route’.” Edmonton Journal, 9 February 1973, page 1.

[32] “MacKinnon – A solution appears to be near in the debate that has raged 17 years.” Robin Barstow. Edmonton Journal, 26 January 1981, page 21.

[33] “‘No alternatives to MacKinnon route’.” Edmonton Journal, 9 February 1973, page 1.

[34] “Planners oppose MacKinnon ravine road.” Edmonton Journal, 22 June 1974, page 3.

[35] “MacKinnon – A solution appears to be near in the debate that has raged 17 years.” Robin Barstow. Edmonton Journal, 26 January 1981, page 21.

[36] “Council kills roadway vote.” Barb Livingstone. Edmonton Journal, 13 May 1981, page 17.

[37] “MacKinnon – A solution appears to be near in the debate that has raged 17 years.” Robin Barstow. Edmonton Journal, 26 January 1981, page 21.

[38] “Stitch in time for guest.” Maureen Hemingway. Edmonton Journal, 17 June 1984, page 16.

[39] “MacKinnon Ravine crusader dies; Margaret Chappelle’s estate estimated in millions, but will can’t be found.” Ross Henderson, Helen Plischke. Edmonton Journal, 12 July 1992, page 11.

[40] “A Reclusive Activist – Artist’s legacy goes far beyond $3.7M gift to SPCA.” Stephen Erwin. Edmonton Journal, 24 January 1993, page 11.

[41] “Margaret Chappelle – Edmonton’s 100 Century.” Edmonton Journal, 3 October 2004, page 96.

[42] “Restore MacKinnon.” Edmonton Journal, 12 June 1984, page 6.

[43] “Stitch in time for guest.” Maureen Hemingway. Edmonton Journal, 17 June 1984, page 16.

[44] “New park approved for ravine.” Edmonton Journal, 11 November 1987, page 17.

[45] “A Reclusive Activist – Artist’s legacy goes far beyond $3.7M gift to SPCA.” Stephen Erwin. Edmonton Journal, 24 January 1993, page 11.

[46] “A Reclusive Activist – Artist’s legacy goes far beyond $3.7M gift to SPCA.” Stephen Erwin. Edmonton Journal, 24 January 1993, page 11.

[47] “Artist’s $3.7M left to city’s SPCA.” Stephen Erwin. Edmonton Journal, 19 January 1993, page 1.

[48] “A Reclusive Activist – Artist’s legacy goes far beyond $3.7M gift to SPCA.” Stephen Erwin. Edmonton Journal, 24 January 1993, page 11.

[49] “A Reclusive Activist – Artist’s legacy goes far beyond $3.7M gift to SPCA.” Stephen Erwin. Edmonton Journal, 24 January 1993, page 11.

[50] “Artist’s $3.7M left to city’s SPCA.” Stephen Erwin. Edmonton Journal, 19 January 1993, page 1.

[51] “Saving Parkland.” Margaret Chappelle, Letter to the Editor. Edmonton Journal, 24 March 1965, page 15.

[52] “We have no right to destroy this beauty.” Margaret Chappelle. Edmonton Journal, 7 January 1965, page 6.