Introduction

Located in the Ottewell neighbourhood, the Baitul Hadi Mosque (House of Guidance) has served the Ahmadi Muslim community in Edmonton since 1997. Previously a church, the Ahmadiyya congregation repurposed the building to accommodate the many activities the local chapter engages in, such as congregational prayers and educational classes. It is one of two Ahmadiyya mosques in the province of Alberta (the other being the Baitun Nur Mosque in Calgary), and continues to play a significant role in expanding and hosting Ahmadiyya activities in Western Canada.

Background on Ahmadiyyat Movement in Islam

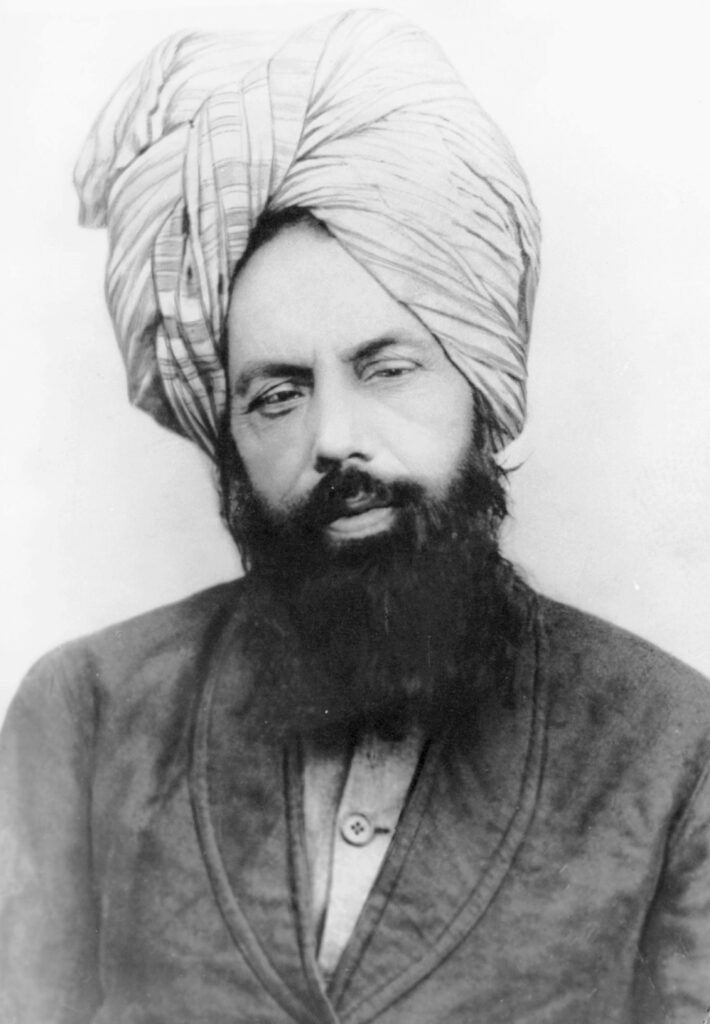

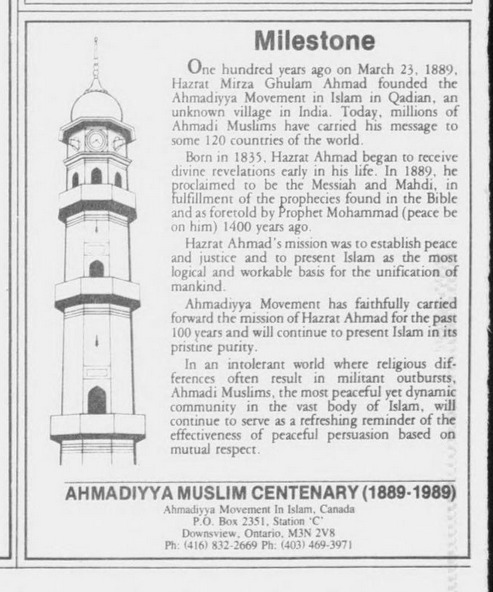

The Ahmadiyya are one of the many denominations of Muslims within Islam. Founded by Mirzā Ghulām Ahmad, a Muslim reformer in 1889 during the period of the British Raj in South Asia, Ahmadiyya consider themselves as a revivalist sect with a global membership of across 200 countries.[1]

To understand the establishment of the Ahmadiyya Movement, one must look at its early history. Born into a Sunni landowning family, Mirzā Ghulām Ahmad was born in the city of Qadian in what is now known as Northern India during the late-nineteenth century. Upon receiving a formal education in Persian and Arabic, he saw himself as a Muslim reformer and sought to defend Islam against the increasing prevalence of Christian missionaries. By 1900, his followers began preaching in places such as Fiji Islands and Kenya.[2] As followers of Mirzā Ghulām Ahmad, the Ahmadiyya observe a few key distinct practices and beliefs; namely the succession of a Khalifa or spiritual messiah, their commitment to missionary work and the sacredness of their holy sites in the cities of Qadian (Indian Punjab) and Rabwah (Pakistani Punjab).

Such practices and beliefs have often put the Ahmadiyya at odds with more dominant Muslim practices. For example, while the Ahmadis see the role of their Khalifa as one that is “a divinely given conduit between God and the community of believers on earth,” the dominant Sunni Islam sees the continuation of a prophethood after the founder of the faith, Muhammad (as) as apostasy. [3] As a result, Ahmadis have faced persecution for their beliefs in countries such as Pakistan, where they are legally considered as non-Muslims and are barred from calling their places of worship mosques, disallowed from participating in civic elections, and even from making the call to prayer among many other restrictions.[4]

Despite the continued discrimination the Ahmadis face, one of their enduring strengths has been in organizing communal gatherings, namely the annual Jalsa Salana. Held in many countries, in Canada this annual conference is organized regionally and brings together Ahmadi community members in both western and eastern Canada. During the three-day gathering, members are addressed by religious leaders and have the opportunity to meet and engage with other members. In the Urdu language, the term ‘Jalsa’ means “convocation” or “fete” and ‘Salana’ means ‘annually’. In 2020, most Jalsa Salana events were cancelled across the globe due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and in 2021, the primary Jalsa in the United Kingdom was limited to invited masked, double-vaccinated attendees.[5] In every Jalsa, the current Ahmadi Hazrat addresses all who have gathered.His speeches are broadcasted globally via the online platform Muslim Television Ahmadiyyah International.

Background on Baitul Hadi Mosque

For Ahmadi Muslims in Edmonton, the Baitul Hadi Mosque represents a firm anchor in community. The mosque hosts a growing community of 700 registered members who primarily trace their origins to the South Asian Subcontinent. Baitul Hadi offers a number of conventional services such as Friday prayers, Eid celebrations and community programs such as religious instruction for children and youth. In terms of the mosque’s organization, there are several auxiliary groups including the Ladjna Ima’illah, a group for women aged 15 and up. The Ladjna not only focuses on religious instruction for Ahmadi women, but also fundraising and in some congregations, sporting events for women.

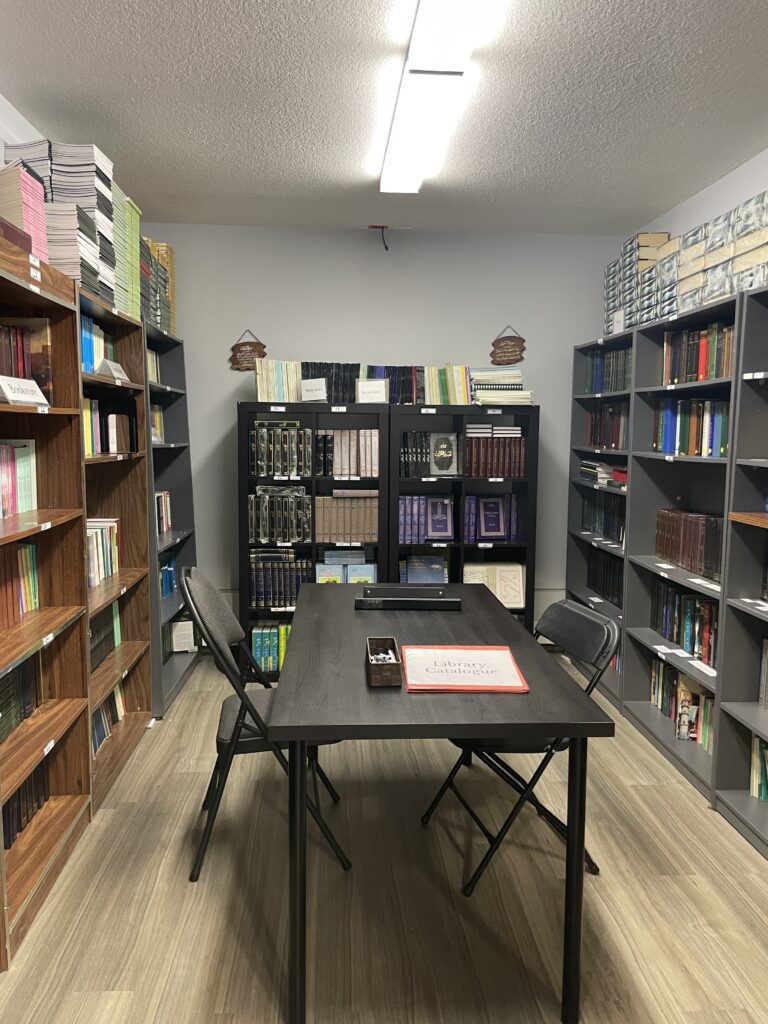

Upon purchasing the building in 1997, the Ahmadis undertook the renovation of the primary hall and main entrance of the former church. What was once the primary hall is now a gymnasium and a library, both underscoring the Ahmadiyya’s commitment to overall health and continuous learning. The mosque has two prayer halls which segregate the sexes, a kitchen, library and several classrooms for educational instruction. Additional renovations in 2016 saw the building transform once again to feature more elements that are more commonly associated with mosques such as a dome, minarets and Islamic calligraphy. Though it many seem that these features would be commonplace amongst mosques in the Levant and even North America, employing the symbols of Islam and formally recognizing their place of worship as a mosque allows the Ahmadi the freedom to practice their faith without immediate repercussions or legal persecution from the state.

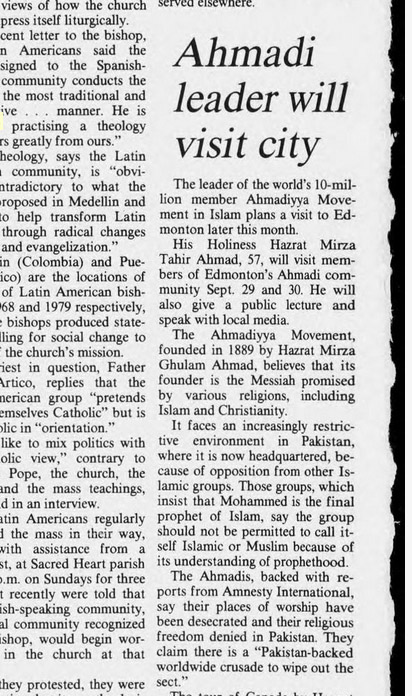

One of the highlights in the community’s history includes a visit from the 4th Ahmadi Caliph Hazat Mirza Tahir Ahmad to Edmonton in 1986. During his two-day visit to Edmonton, Hazrat Mirza Tahir Ahmad met with members and delivered a public lecture. An article in the Edmonton Journal from the time mentions that the Hazrat not only visited congregants in Calgary and Vancouver, but also laid the first foundational stone of the first purpose-built Ahmadiyya mosque, the Baitul Islam Mosque in Maple, Ontario. But perhaps what was the most significant aspect of the Hazrat’s 1986 trip was how it raised significant awareness in the diversity of Muslim beliefs in Canada and about the increasing persecution of Ahmadis abroad. This message continues to have resonance with the Ahmadiyyah Muslim Jama’at today.

More recently, the Baitul Hadi made headlines for hateful vandalism spray painted on the Mosque. The vandalism came days after an attack on a Somali Muslim woman in Edmonton (one of several) and a little over a week after the murder of the Pakistani-Canadian Afzal family in London, Ontario.[6] These perilous incidents underscore how Muslim Canadian communities are vulnerable to acts of hate and white supremacy. Though long the message of the Ahmadiyyat, the phrase “Love for All, Hatred for None” now adorns the exterior walls of the mosque.

In Canada, the Ahmadiyya are a group within a diverse and multi-ethnic Muslim community. The Baitul Hadi Mosque is one of at least twenty mosques and prayer spaces in the City of Edmonton. Like many Muslim community groups, their educational, charity, and outreach initiatives continue to define the Ahmadiyya, and more importantly, are what drives their communal efforts for the future.

© Nadia Kurd 2021

The author would like to thank Imam of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jama’at in Edmonton, Nasir Butt, for his insights and support.

[1] “About Us: Ahmadiyyah,” Ahmadiyya Muslim Jama’at. https://www.ahmadiyya.ca/public/ahmadiyyat (accessed 9 September 2021).

[2] Jonker, G. ” The Founder and His Vision,” The Ahmadiyya Quest for Religious Progress. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2016, 13.

[3] Gualtieri, Antonio. Ahmadis: Community, Gender, and Politics in a Muslim Society. McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2004, 38.

[4] “Pakistan Ensure Ahmadi Voting Rights,” Human Rights Watch, https://www.hrw.org/news/2018/06/28/pakistan-ensure-ahmadi-voting-rights (accessed 9 September 2021).

[5] “Jalsa Salana: Thousands head to Alton farm religious gathering,” BBC UK, https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-hampshire-58127967, (accessed 9 September 2021) .

[6] “Edmonton mosque vandalized with painted swastika,” CBC,

https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/edmonton/edmonton-mosque-vandalized-1.6067306, (accessed 9 September 2021).