CARIWEST – Caribbean Arts Festival was introduced to Edmonton in 1984. It was created by Western Carnival Development Association (WCDA) and is the legacy of the new emerging Caribbean-Canadian immigrant community. Organizers stage the Downtown Parade as their signature event. The germ of the festival was first sown by Caribbean students in the 1960s and 1970s, who annually staged a period of Caribbean musical performances, drama productions and local performing events on postsecondary campuses. Despite their primary objectives to pursue postsecondary education, the students also brought with them parts of their heritage and culture. Prior to 1984, the group took their masquerade, dancing and musical expertise to Edmonton’s Klondike Days parade, which included an assortment of decorated vehicles, livestock, tractors, and small business displays. Organizers wanted a different platform to present their cultural treasures. An independent festival similar to a Caribbean-styled carnival which was their heritage, would better represent their aspirations, and would showcase their music, dance and masquerade performances.

Festival organizers needed to demonstrate a growing community presence and the Caribbean feeling of ‘home’ away from their sunny islands, while striving to merge this new festival within the broader, emerging multicultural environment. Michael LaRose1 described “the Caribbean Carnival as the creative and artistic expression of dispossessed people,” seeking to settle in a new space and environment. “The Caribbean Carnival [model] has been transported to North America and Europe through the migration of Caribbean peoples.”

Cariwest and the Caribbean-Style Carnival

Immigrants from the Caribbean came to Canada with their cultural practices including their ‘Carnival’ celebration. These new diaspora communities created new Caribbean-style carnival festivals where ever they established their communities. These include Cariwest in Edmonton, Caribana in Toronto, Carifiesta in Montreal, Carifest in Calgary, Notting Hill Carnival in the UK, Labour Day (Carnival) in New York City, Miami Carnival and other cities where there are diaspora communities. These festivals have enhanced the vibrancy of cities like Edmonton where they have been created and identified new emerging communities. They are all examples of this transference of heritage culture. Cariwest has had an unbroken run since 1984.

But where do these masquerade creations, this gay abandon, this joie-de-vive – indeed this creativity, these ‘carnivals’ – come from? Embedded in the psyche of these African-Caribbean (especially those from Trinidad) immigrants is the traditional celebration called Carnival. It dates back centuries to their ancestors’ enslavement in the Caribbean region, when the enslaved peoples would be given time off to celebrate a successful and profitable sugarcane harvest. They would parade in the streets in their plantation owners’ discarded dresswear.

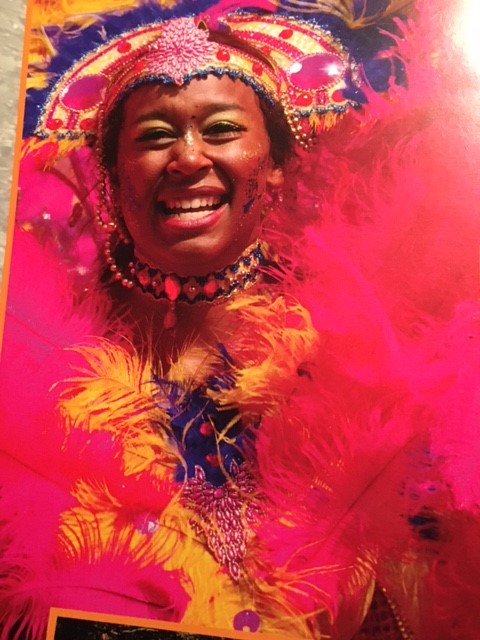

Sometimes under the cover of darkness, buildings and property would mysteriously be torched to express their resentment to their enslavement. “If you see people doing things on the street on carnival day, it’s something that has evolved from all that repression of slavery,” says Selwyn Jacob.2 Very often their faces would be covered to hide their identity; this masking is another part of the ancestral heritage associated with the carnival festivals. According to Candice Maharaj,3 “participants would often take advantage of the anonymity provided by masks, costumes and crowds to be as carefree – and sometimes as lewd – as they wanted. Subverting social norms was a significant theme in traditional carnival celebrations. Costumes would often mock authority or upper-class culture and would even depict the devil.” Very often, faces in the Cariwest parade are covered. They reflect this historical practice. This is also reminiscent of practices in Western Africa, particularly Nigeria. These celebrations are also traditionally and historically linked to the famous carnival celebrations of Brazil, and New Orleans – Fat Tuesday/Carnival Tuesday/Mardi Gras.

Adapting/Changes to Carnival Celebrations in Canada/Edmonton

Geographically, because of normal climate conditions in metropolitan countries, carnival/festival organisers made a conscious decision to shift the timetable for carnival celebrations in diaspora communities to the ‘warmer’ summer months, instead of the traditional period proceeding Easter. Hence, Edmonton’s Cariwest Festival is generally staged in early August, close to Toronto’s Caribana. It draws participants and an audience from across the Prairie provinces; from Seattle/Vancouver, from Winnipeg, from Saskatoon, from Fort McMurray and Calgary, from Los Angeles and Toronto, masqueraders descend on Edmonton to participate in Cariwest. There is a concerted attempt on Cariwest’s part to embrace other world communities that celebrate a carnival similar to the Caribbean-style celebration of Edmonton. In the words of Selwyn Jacob2, an early Presidents of Cariwest/WCDA:

“I felt that carnival should expand beyond the boundaries of the Caribbean community… I thought if you can make inroads into some of the communities at large, anybody who can identify with the spirit of Cariwest should be allowed to come in. I think maybe that’s one way that they have progressed. One of the reasons we actually call the celebration Cariwest is that we knew that Edmonton did not have the infrastructure to support a carnival by itself. So, there’s a time when we had bands coming in from Winnipeg, from Calgary, from Vancouver, and it truly was a western carnival…But also, I think we also had the vision of going into the classroom and teaching the kids about making costumes.”

This is the time of the year when Edmontonians also invite relatives and friends to visit. It is Cariwest time, when we display that triumphant spirit, the joy that street theatre and dancing in the street brings, the time of gay abandon, when we parade our carefree attitude about life. This is our therapy. This is how art imitates life. This is when we showcase our city and demonstrate how welcoming Edmonton has embraced the presentation and inclusion of our immigrant cultures.

Impact of Cariwest in Edmonton

A fundamental part of the festival presentation is the musical accompaniment, the Caribbean rhythms that explode on the streets especially during the parade, rhythms that underscore the intent to ‘have a good time’. The music engages the observer, enticing one to move, to dance, to respond. Pulsating Caribbean music including reggae, zouk, soca, and other musical forms beckon the listener. But the novelty in the parade is the music played on ‘steeldrums’ or the ‘steelband’. From Trinidad & Tobago, this is reputedly the only acoustic musical instrument invented during the 20th century and is made from discarded oil drums. Under the leadership of Cecil George, Cariwest’s first President, Edmonton has created its own ‘steelband’ aggregation – the Trincan Steel Orchestra.

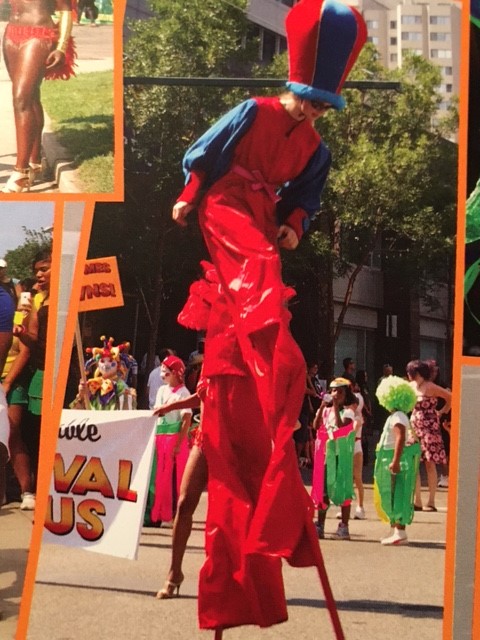

Stilt Walking: A Symbol of the Caribbean Carnival Arts

Developed in our city is the presence of stilt walkers. Though not credited to Cariwest, stilt walking is also part of the Caribbean diaspora experience and known as ‘Moko Jumbie’. Its proponents in Edmonton are also of Caribbean heritage and learned the art in the Caribbean region where training is available from a very young age.

Did you sneak a peek of the gigantic Cariwest costume at the Edmonton International Airport (EIA) a few years ago? Or the elaborate Queens’ costumes on display panels on the walls of the Edmonton International Airport? This is the kind of impact and presence Cariwest has had in this city. The gigantic costume, dedicated to Edmonton and our province’s farming community was called “Sweet Wheat” and was the outcome of an international costume construction workshop staged at the University of Alberta’s Faculty of Education in 2008-2009. The community-based workshop was led by qualified veteran instructors from the Caribbean experience. The mas’ (short for Masquerade) project – Mas Goes to University – assembled welders and other construction technicians to train in moulding, fabricating, wire bending, and costume creation and assembly. Scores of giant foot-long bees and hundreds of wheat pods were created to attach to the massive 30-foot high wheat costume that appeared in the Cariwest parade that year. It was truly a work of art that rose out of the depths of local creativity. University personnel, full of pride in this joint community venture, brought students and faculty visitors to the construction and training space. Following its downtown parade, Sweet Wheat was displayed at the Edmonton International Airport.

The Structure of the Cariwest Parade

While appearing to be very loosely structured, carnival or masquerade bands are highly organized with ‘queens’, ‘kings’, ‘individuals’ and ‘floor members’ or the general masses, as the largest part of the band’s population.

Generally based in diaspora communities and grouped into masquerade bands, the planning begins with the ‘band’s’ decision of a theme for its festival presentation. Will they use a historical theme? a contemporary theme? a local theme? an abstract theme?

Having made that decision, the group sets up its ‘Mas Camp’, the location where production would take place, where community meets to contribute countless hours of cutting, sewing, gluing, painting, welding, fabricating, and generally bringing the mas alive. The Mas Camp could be a garage, a basement, a covered area of a backyard, a rented bay or community common space. The theme has to be represented in the “mas” or masquerade that is created.

The group – the band- is organised into sections or groups of floor members that compliment each other and reflect the theme. Each section will have a section leader – male, female or both – and the entire band will have a ‘king’ and ‘queen’.

Their majesties’, the King and Queen, costumes require the primary attention of the designers and fabricators. They are usually constructed on a wire frame that is moulded, bent and welded together as the foundation for each costume. They can each measure 20-30 feet tall and 15-30 feet wide. A key principle is that they cannot be motorised. These are costumes that must be danced, pranced, paraded, with elements worn on shoulders, waist, feet, hips. The wearer is responsible for their movement. Designers have to bear these features in mind as they create these thematic pieces that represent the entire band’s theme/topic for the year.

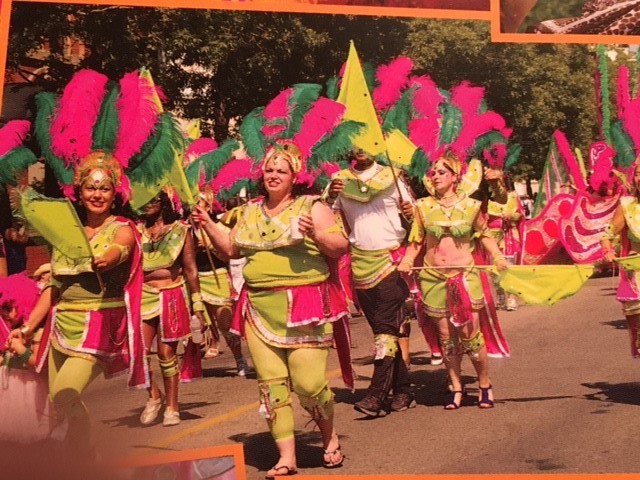

The Floor Members’ costumes are produced assembly line style. Basic skirts or pants will be embellished with sequins, ribbons, feathers, decorative foam, or other additions to add to their statement or attraction. The floor members, the masses of the mas band, are the engine room of the band and the production process of the band evolves around them. Floor members’ costumes included (1) a standard to be held in the hand, (2) a headpiece for head wear, (3) the body piece, in whole or parts, and additional decorative pieces for arm, legs and face. The Section Leaders have more elaborate parts of the floor member’s costume.

Once all of the construction is complete, the band can prepare for pre-parade competition and mounting excitement, as well as friendly rivalry among the city’s groups. The band is ready for Parade Day.

What Do Onlookers See in a Cariwest Parade

The spectacular gigantic ‘king’ and ‘queen’ costumes dance down Jasper Avenue. Unaided by anything mechanical, the wearers prance in the August sun. The kings and queens are the largest of the carnival band’s costumes. They are followed by sections of ‘floor members’, wearing smaller images of the band’s theme. Based on the Band’s theme, onlookers may see life-like bees as headpieces, imitations of historic Egyptian royalty, biblical characters in simulated horse drawn carriages, waves and beach debris displaying a climate change consciousness, stilt walkers, animals of all sizes and description, la diablesse (the devil), Caribbean Indigenous performers, butterflies, flora and fauna, birds of different feathers, Brazilian dancers, flags of the world, ‘bamboo dancers’ and more. The variety of costumes is endless, representing different themes for different bands.

It is the annual colourful Cariwest parade of thousands of costumed revellers with pulsating Caribbean rhythms and musical aggregations; with everyone dancing on the street on their feet this is one humongous street party. It is a Downtown Edmonton summer special and you have just got to be there.

Cariwest Beyond Edmonton

Cariwest has placed Edmonton on the global map of Caribbean-style carnivals held in cities around the world, has attended international carnival arts conferences and has networked with similar diaspora communities. The unspoken blueprint of Caribbean diaspora communities around the world is the same – to proudly fuse and represent the triumphant spirit of diaspora communities united in purpose and collective fervour Carnival is a worldwide industry – of designers, arts engineering, fabricators, producers of essential items like feathers and beads, specialized foams, fabrics and adhesives, welders, and moulders. Organizers host a world class event annually through their enthusiasm, sustainability and creativity, their pride, commitment and dedication to contributing to the multicultural landscape.

Donna Coombs-Montrose © 2021

References are Made to:

Michael La Rose, “History of the Caribbean Carnival,” January 23, 2015. CharlestonCariFest.com. https://charlestoncarifest.com/information/history-of-the-caribbean-carnival/

“Selwyn Jacob,” 2013. AlbertaLabourHistory.org. https://albertalabourhistory.org/selwyn-jacob/

Candice Maharaj, “The Origins and Evolution of Carnival in Trinidad and Tobago,” November 11, 2018. RetrospectJournal.com. https://retrospectjournal.com/2018/11/11/the-origins-and-evolution-of-carnival-in-trinidad-and-tobago-2/

Other Sources Consulted:

“History of Caribbean Carnival,” December 14, 2020. CariViews.com. https://www.cariviews.com/blog/history-of-caribbean-carnival

Michelle Parson, “Carnival – A Festival of Freedom and Creativity,” 2021. TorontoArtsCouncil.org. https://torontoartscouncil.org/blog/posts/caribbean-carnival