My journey towards becoming an educator started in my childhood with time spent under a mango tree at my home in Trinidad and Tobago, trying to impart the rudiments of basic education to a motley crew of inanimate students: a worn straw broom, a disheveled, and several obstinate enamel bowls. It was in 1961, however, at the age of twelve that my first formal success in the post-colonial common entrance examination propelled me to universal education and admission into the most prestigious Girls’ high school in my region with a full scholarship.

I became the model for Blacks and the economically poorer populace. As a ‘first’ for my community, my parents believed that it was my duty to share my gift with the community. Hence, for the duration of my entire high school years, I tutored “crops” of prospective exam candidates while completing my own studies. It was then that I discovered what is known now as peer tutoring.

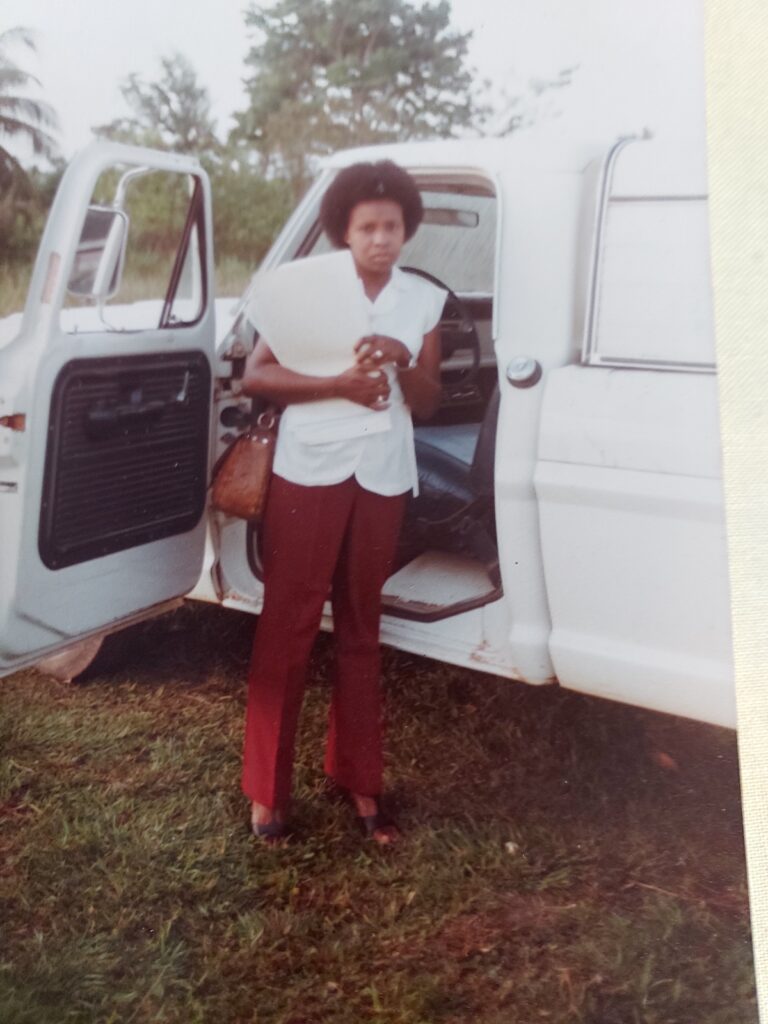

As was the custom in the Caribbean in the 1960s, high school graduates with excellent grades from the British-administered General Certificate of Education were given teaching positions, without formal teacher training. I was employed thusly for a few months, first in my hometown elementary school, then transferred to a high school in Tobago. That tenure was short-lived as I was married that same year and my new marital status qualified me, through the point system, to immigrate to Canada in 1967.

My journey took my husband and me to Montreal, then Vancouver and finally Edmonton, but employment was difficult to come by despite the assistance of Canada Manpower Services, a government job-finding agency. I was advised to take what work was available: delivering telephone directories, sorting mail at Canada Post at Christmas, and working for the Levi Strauss/Great Western Garment Company.[1] The three-day stint at the latter allowed me to teach some functional English to my co-workers and make up for my ineptitude at sewing. Canada Manpower Services also used me as an unofficial ambassador for newcomers by sending each new arrival from the Caribbean to my house where I held classes for many single men, teaching them how to read a city map, take the bus, navigate bus routes and addresses, and do housekeeping. On Sundays, they attended Sacred Heart Catholic Church on 108th Avenue and 96th Street with me, and then to my place for a home-cooked meal. [2] It felt very much like present-day Catholic Social Services but operating only through my personhood.

My first job offer was dishwashing at a college. I later learned from co-workers that before I was hired the cook had asked my Greek and Ukrainian co-workers whether they would have any problem working with a Black person. Within the first week of employment as a dishwasher, I traded dishwashing duties for helping students on campus with their homework.

At a prospective interview for a meatpacking job the receptionist made it a point to shout to the interviewer, “There is just one more here but she’s Black so that’s it for you today.” She smiled at me knowing that she did not have to even tell me to leave. After several incidents like these, I prepared a standard answer for the commonly asked interview question: “How do you feel being Black in…?” My standard answer was: “I don’t know, I have always been Black. How would you feel?” Throughout this period of bouncing between jobs, employment in education was still my goal.

Unable to find employment in Edmonton, I accompanied my husband to Whitecourt where he accepted a position as a guitar instructor in a private music school. I took the opportunity to teach the accordion as a means of polishing my music skills and to understand parents and children in Canadian society. However, qualifying to teach in Edmonton’s public school system continued to evade me. I had my school transcripts evaluated and they were devalued at a Grade 11 level. By happenstance, I found a way to qualify for entry to post-secondary studies: I took the diploma exams as a private student with resulting outstanding grades and a sizeable grant for the first year of study in the Faculty of Education at the University of Alberta. I majored in English and Special Education, changing the latter to French after I learned that Special Education students were not integrated into the school system but were institutionalized at that time.

In 1971, I was confronted with a question on my mid-term exam that asked me to validate the trending Arthur Jensen theory. Jensen claimed that people of African heritage were not as biologically intelligent as Whites. My choice to not answer the reprehensible question earned me an ‘Incomplete’ on my transcripts. The next year in a course on Victorian English, my intelligence was once again questioned when a heavily weighted paper I completed was withheld, and I was subjected to questioning as to its originality. Despite the professor’s unproductive search for the sources of my alleged plagiarism, evidence of changes made in my own handwriting, and answers that were verbatim from my essay, I was told that “Although my essay deserved more than a ‘9’, I was given a failing grade as I was incapable of writing such a sophisticated piece.” A hearing by the Dean of Education only earned me a ‘5’ as my professor contended that she had only said that the paper was “better than a fail.” Despite the alleged “poor quality” of the paper, she followed my progress in every subsequent English course to advise my current professors of my ‘cheating ways’ which they told me about.

The racism continued to plague me during my four years of undergraduate studies and beyond, but never so much as to deter me from being a teacher. I continued to share my skills with the Black community by instructing 50 or more Tanzanian educators about Canadian life and culture. They had been brought to the Faculty of Education for a two-year Education Aid program in 1973.

Immediately upon graduation, with outstanding status, I applied to every school board in Edmonton and its environs for substitute teaching. That spring I was never unemployed as I worked on a first-come-first-served basis. Meanwhile, I applied to the same school districts for full-time permanent positions. I was given several contracts but ultimately accepted one for a junior high school with the Edmonton Catholic School Board.

My education from childhood and through my life as a high school teacher, English as a Second Language Teacher, Student Counsellor and later a Teacher Consultant were entirely Eurocentric. An Indigenous friend once told me that it was costly studying to be a Christian church minister because he had to learn how to live in a White Man’s world, and then unlearn it to be an Indigenous person in it. He ended his statement with, “you would know what I mean, right?” I did.

Having attained my first goal, I felt like him: that the education I had received so far had taught me to devalue myself. From the textbooks in my colonial childhood that depicted Blacks as non-persons to how they were treated by media, I realized that we were seen as below humans: second-class citizens. I did not want this for my children or any children. “Their” stories of us were never “our” stories. The only “misadvantage” was that it prepared me for the Eurocentric world of Canada. In order to right the wrong of being thoroughly colonized, I returned to the Caribbean to work with Caribbean Examination Council Administrators. I did this so that the generations coming after me would have a different sense of ‘self.’ For 10 years, that was my quest. While in Trinidad and later Belize, I taught high school but continued to serve the community in other ways. In Belize, I started a literacy program for the parents of my students, taught them how to create a cottage industry by canning fruits found in their backyards, and successfully lobbied the government for amenities such as running water and electricity.

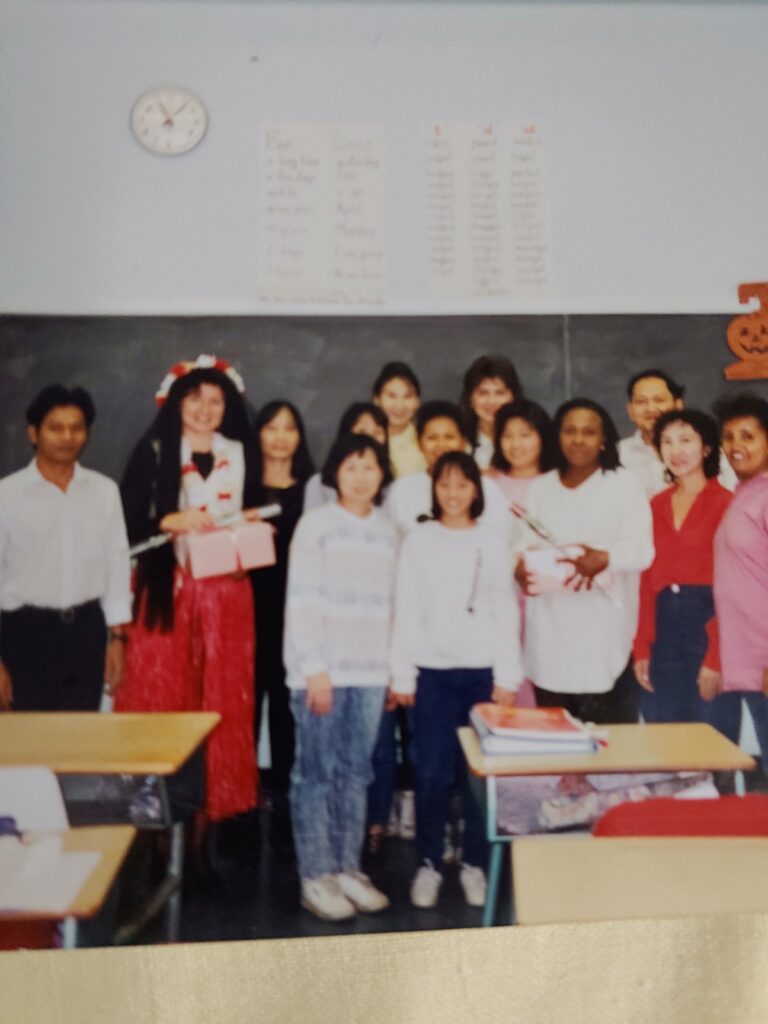

Upon my return to Canada in 1989, I noted that although the African-Canadian population had increased immensely, there was still an absence of Black Studies in the curriculum except for one program. In addition to my regular teaching job, as president of the Council of Canadians of African and Caribbean Heritage, I co-founded CCACH tutoring with like-minded educators. My initial goal was to have 3rd and 4th year post-secondary students with a lived experience of being Black in the Canadian school system offer one-on-one tutoring to the students in studies below them, meanwhile benefitting from the expertise of qualified Black teachers as their coaches. Initially, our tutors were all volunteers, but I later found a way to pay them for the time that they would have otherwise spent in minimum wage entry-level positions.

Tutors received workshops on topics such as building rapport with students, teaching Reading effectively, healthy work ethics, pedagogy in different subject areas, and African/Caribbean culture. Since they came from Africa and the African Diaspora, they learned about each other. In addition to improving their grades, tutees had access to an understanding ear for their concerns and readily available role models.

CCACH tutoring worked: students improved in their academics as well as in self-esteem. One example of racism was when a student came to tutoring in a sullen mood and stated to his tutor, “I don’t want you to teach me too much because my teacher does not like it.” Upon questioning the student and talking to his mother, it was discovered his report card was withheld because he was the only one who received 100% in math. Despite his explanation that he was being tutored, it was alleged that he must have had the teacher’s textbook given to him with the answers. Of course, this was incorrect. Even when supervisors of the program advocated for the student with the teacher involved and the principal of the school, the grades were grudgingly given, and the student continued to be victimized.

There was also the issue of combating the negative stereotypes that have been accepted as the norm in the education system. Attempts to have Black Studies integrated into the curriculum had gone no further than an acknowledgement that there was a need for it from the powers that be. Thus we had to create it ourselves. The opportunity came when Malcolm Azania, then an education student at the University of Alberta, created a Jeopardy-like competition on Black History for members of the University’s Black Students’ Association. I conferred with Malcolm and introduced it to elementary, junior and senior high school students. Afro-Quiz was born as an avenue through which authentic information about ourselves and Black achievement could be imparted to our community. Inside their day-to-day classrooms, I wanted our Black students to be able to raise their hands and say, “ Do you know that it is a Black person who invented the idea of cord blood, or the traffic light, or laser eye surgery?” For close to 30 years Afro-Quiz has been operational in Edmonton, again through the auspices of CCACH.[3] Among regular participants were Indigenous students from Prince Charles School who were introduced by a Black teacher and Psychologist, Delores Jack. Many of her students would place in the first three positions in the competition. At one point I felt that it was hypocritical of us to have our Indigenous students learning about our history when they had a rich culture that was not taught in schools. Mrs. Jack and I discussed it and Aboriginal Quiz was founded subsequently.

Despite the Black community’s concerted efforts to have Black Studies included in the Alberta Social Studies curriculum and attendance at many focus groups at the University of Alberta and with Alberta Learning, the issue has thus far been met with little success. At present it has been relegated to “here are some resources for teachers. They can choose to use them as references.”

The fight continues: I will continue to instruct us about us.

Jeannette Austin-Odina © 2021

[1] http://gwgpiecebypiece.ca/en/history/edmonton.html.

[2] On the first Sunday after our arrival, my husband, his friend and I attempted to attend the French Church across from the Sacred Heart Church- The Church of the Immaculate Conception. However, just before we sat down in a pew at the back, the priest accosted us and without a greeting or question, said, “This is not your church. Yours is over there.” He pointed to the church across the street. We gathered our prayer books and left. See https://sacredpeoples.com/history/.

[3] Fatsani and Melody speaking to Global about Afro-Quiz, https://globalnews.ca/video/3989148/afroquiz-2018-fundraiser-january-27th. Snippet of Afro-Quiz with Jeannette talking about the longevity of Afro-Quiz: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OFzGUBiUW74.