The flights touched down at a Canadian International Airport bringing scores of eager Caribbean nationals, their suitcases packed with their aspirations, their heritage, their culture, their fists pumped, chests bursting with pride and expectation, they brought the best of themselves. They were immigrants from the complex Caribbean area – people from British, Spanish, French, and other territories; they were peoples of mixed colonial heritage, Creoles, Mulattoes, Afro-Caribbean citizens linked by common seas, common anti-colonial struggles, resilient people, full of determination to survive, and to succeed at contributing to their new society.

This was not the first arrival of Caribbean people to Canada. Caribbean-born Black people had been contributing to the creation of Canada’s Black community for centuries. As early as 1746 some 600 Maroons were dispatched from Jamaica to Nova Scotia. Maroon Hill in Nova Scotia remains as a testimony to their arrival centuries later. Nova Scotia’s mines and other business enterprises along the Eastern seaboard, as well as modest migration schemes, also attracted Caribbean labour during the decades following this period. One such scheme was the West Indian Domestic Scheme from 1955-1967 which was established as a pipeline for immigration of women from Jamaica and Barbados. One hundred Sleeping Car Porters also came to Canada annually from the British Caribbean under a similar arrangement, earlier in the twentieth century.

When Federal immigration restrictions were relaxed during the 1960s, it acted as a stimulus for Caribbean immigration. The 1962 Immigration Act reduced emphasis on nationality and racial immigration. The newly introduced Point System based on education and occupational skills, attracted thousands of Caribbean nationals in pursuit of post-secondary education and new professional skills. When racial discrimination was removed as a feature from the modified immigration rules, Canada accepted over 64,000 people from the Caribbean between 1960-1971. With western industrial expansion and enhanced social and economic opportunities, hundreds of new arrivals made their way to western cities and provinces.

The new arrivals who chose Edmonton made the best of the environment and settled in to university courses and programs, domestic employment in the homes of the well-to-do, and technical school at NAIT. Some came with technical skills from petrochemicals-producing islands and pursued employment in their professional areas.

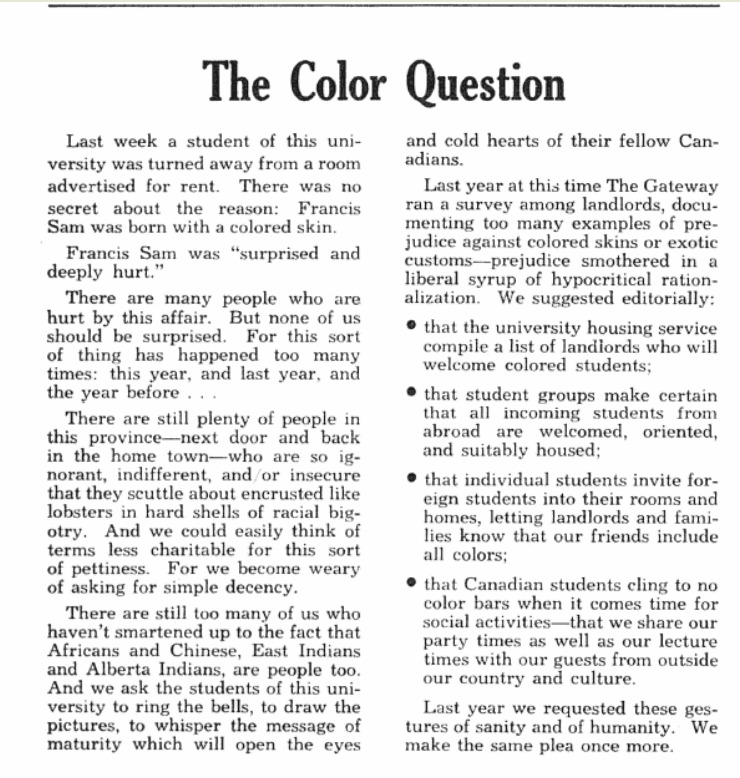

The newcomers sought student housing around Edmonton’s campuses and community housing in areas like Mill Woods, Londonderry, and other low-income areas in Edmonton. Some reported negative experiences in their hunts for accommodation, surprised that among the positive opinions of their new community, there were those who harboured racist resentment. The Gateway featured an article entitled “The Color Question” – “Last week a student of this university was turned away from a room advertised for rent. There was no secret about the reason: Francis Sam was born with a colored skin. Francis Sam was “surprised and deeply hurt.”[1]

Mr. Sam did not quite fit the description of a “suitable tenant.” Added to this experience, it was soon realised that other Caribbean students in other Canadian cities were having similar experiences in housing, education, employment. Some resorted to filing Human Rights complaints especially on grounds of discrimination. Institutional racism was far from dead! But they were determined to succeed in spite of the social barriers.

While this root was being planted, a trek was also taking place of Caribbean people temporarily residing in England. Some 550,000 Caribbean British subjects who migrated to the UK between 1948 and 1973 were not granted residency status. Known as the Windrush people, they found their experiences of extreme racism, lack of basic human rights, employment, housing and isolation intolerable and almost unbearable. Members of this community, disappointed with their English experience, set their sights on Canada with many settling in Edmonton.

They sought employment in their chosen professions, in the public service, upgraded their credentials and opened small businesses. Beryl Stelmach, an English-trained nurse, obtained employment in a federal hospital in Edmonton; Delores Barker opened a Black hair studio on Whyte Avenue; Brian Alleyne, a British-trained Epidemiologist recertified his credentials. Barbershops, pharmacies, restaurants and other small businesses began to spring up across the city in ethnic communities to support the needs of the growing Caribbean community.

These two streams of migration to Edmonton presented the very beginning of a Caribbean population with roots in the Caribbean and Britain.

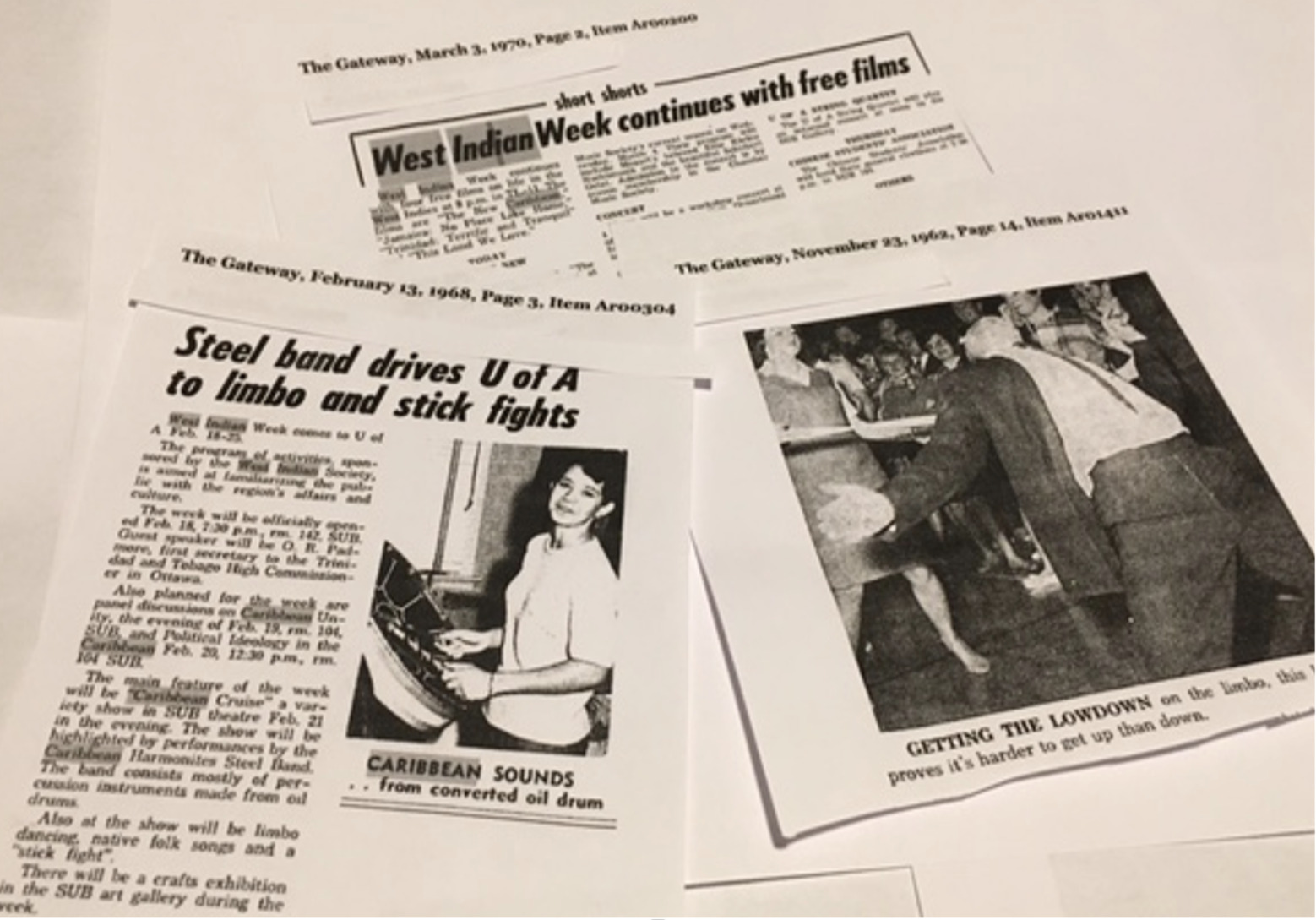

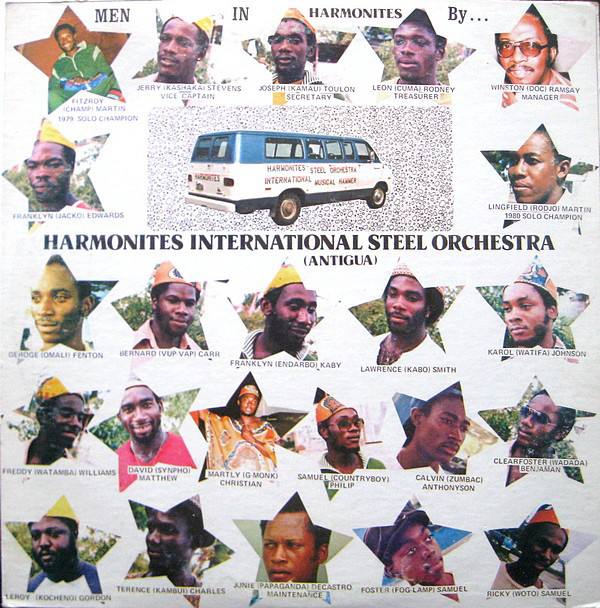

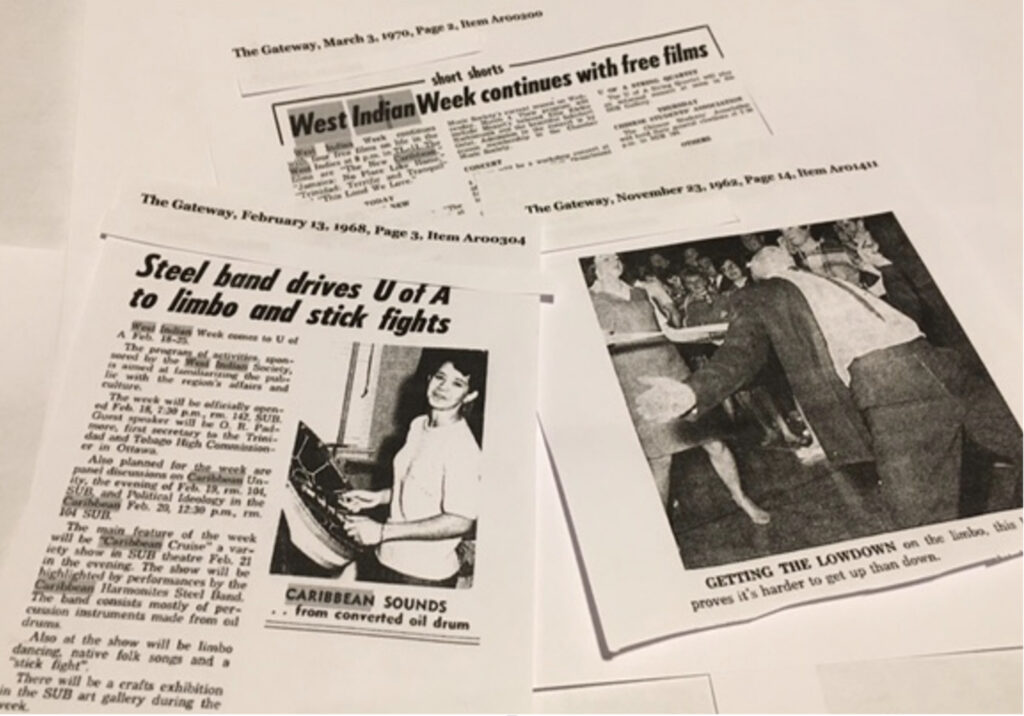

Caribbean students at the University of Alberta were fortunate to be granted a dedicated house on the main campus in the space now known as the Timms Centre for the Performing Arts. They dubbed the existing fraternity-style house “West Indian House.” The space was occupied by some thirty students who shared their food and other resources. From that space students created a Caribbean/West Indian presence at the University of Alberta. They planned a host of Caribbean events annually, hosted a “West Indian Week” to share their culture and history, formed steelbands and other musical groups such as the Caribbean Express Steelband and Caribbean Ambassadors. They organised educational events for classroom spaces, staged film nights, drama performances, limbo dancing and ‘stick fighting’; they connected with off-campus Caribbean communities to create several West Indian musical groups like Tropical Playboys, Harmonites Steelband and others.

Selwyn Jacob, foremost National Film Board Executive Producer, was a member of this nascent Caribbean community and a resident of West Indian House, a communal space that substituted for community. In an interview done in Edmonton in 2007, Jacob recalls:

“When I came here there was something called the West Indian House, and in it we’d have students from St. Vincent, from Jamaica, from Grenada, from Guyana and from Trinidad. So that’s where I lived. It was a co-op in the sense that we brought groceries communally and one person was designated to cook one day per week. It was the hub of the West Indian culture at that time because there was really no organized community as such, anyone who immigrated or was visiting at that time would drop in at the West Indian House. We celebrated something on campus called West Indian Week, where we volunteered to go to the different classes and to talk about West Indian culture and to put on a show. I was interested in the arts at that time so I would put on some of the shows. We would put on a play and just have cultural expressions, reach out to radio stations, CBC and do interviews and that sort of thing. So that was like the precursor to any kind of West Indian community – the West Indian House 11126 87th Avenue. The address is etched in my mind. …If you wanted to have a party while you were going to university and the winter was getting to you, that was a place where people got together It served as a community centre … it was a way of trying to create some of cultural identity… [show] the Canadian public at large what Caribbean culture was all about … so in a way we saw ourselves as pioneers.”[2] They were industrious new Canadians, anxious to contribute to the building of their new society.

Jacob and the West Indian Society also produced 24 segments of a television program – Caribbean Perspective – which featured Caribbean talent on university campuses, visiting Caribbean dignitaries to the region, and representatives of the growing US African-American influenced “Black Power Movement.” Developing a profession in the film industry, Edmonton-trained Jacob went on to produce over 30 documentaries for the National Film Board, and to received several national awards for his contributions to this industry.

Emerging in the new Caribbean communities around Montreal in the late 1960s, Caribbean students at Sir George Williams University (now Concordia University) were waging relentless battles against grading discrimination and academic failure. Caribbean students who had left their tropical isles to pursue post- secondary education in Canada were once again faced with the realities of institutional racism. Earlier in the 20th century, Caribbean students in Queen’s University’s medical programme were unexpectedly dismissed on racial grounds, that patients did not want to be treated by Black doctors. Queen’s University publicly apologised in 2018 for its actions a century earlier. The protest actions of the Montreal students lasted for several weeks and served to expose how deeply racism in higher education was buried. Eventually many of these students completed their medical training elsewhere, including at the University of Alberta, or invested in other professions.

While Caribbean-Canadians were making their mark in other parts of Canada, Edmonton’s newly formed Caribbean community extended its arms to gain a foothold in education, politics, sports, culture and industry. They lay claim to the achievements of renowned Oncologist Dr. Anthony Fields, trailblazer filmmaker/broadcaster/writer and Human Rights Commissioner Dr. Fil Fraser, Open Heart Surgeon Dr. Kevin Baney, a host of international educators like Professor Whitfield Andy Knight, Edmonton Oiler Darnell Nurse and his parents, industrial interests like Trinidad Drilling, a score of independent contractors who service the petrochemical sector, real estate companies and other internationally owned franchises and restaurants.

Left to Right: Dr. Fil Fraser. Accessed at https://news.athabascau.ca/announcements/remembering-fil-fraser-arts-icon-au-prof/. Dr. Anthony Fields. Image accessed at https://www.ualberta.ca/oncology/about-us/index.html. Selwyn Jacob. Image accessed at https://www.chf.bc.ca/event/ninth-floor-a-conversation-with-selwyn-jacob/.

Edmonton’s Black community has made significant contributions to arts and culture. Its 37-year old festival Cariwest, a Caribbean Arts Festival, is a well known city event. The rhythms and culture of the Caribbean region are widely promoted and popularised in Edmonton. Several community organizations were created to foster the community’s development – the Council of Canadians of African and Caribbean Heritage (CCACH) is one pillar that supports academic achievement; women’s organisations like the Congress of Black Women and Caribbean Women Network advance the training and development of women. Other projects and organizations initiated by Caribbean youth now exist to continue building on these achievements. The mantle has been passed.

Donna Coombs-Montrose © 2021

Sources

- https://socialistproject.ca/2019/01/fifty-years-ago-birth-of-black-power-in-canada/

- https://medium.com/ualberta2017/black-history-is-canadian-history-41975830d965

- Fraser, Fil. How the Blacks created Canada. Dragon Hill Publishing, 2009.

[1] The Gateway, September 27, 1963, page 4.

[2] http://albertalabourhistory.org/selwyn-jacob/.