Renaming places in Edmonton has become a major point of public discussion with several renamings occurring, or being proposed, since 2020. One of the more well-known was a decision by the Oliver Community League in favor of renaming the neighborhood as a rightful protest against Frank Oliver, the person for whom the neighbourhood was named. Campaigners cited his prejudicial actions and attitudes in general, as well as his campaign of displacement and racist denigration of the Papaschase Cree specifically as clear reasons why the neighbourhood should no longer venerate him. In another example, the renaming of Edmonton’s wards was finalized in December 2020, with the iyiniw iskwewak wihtwawin (the committee of Indigenous matriarchs) gifting new names to the City, thus replacing the simple numerical ward designations that preceded them. (The Ward in which I live, for example, is now named O-day’min, an Anishinaabe term meaning ‘Heart-berry’ which is meant to invoke the image of “the heart through which the North Saskatchewan River runs.”) A slightly more tongue-in-cheek suggestion was made to rename the Corona LRT Station to Dr. Deena Hinshaw Station after the provincial Chief Medical Officer of Health during the Coronavirus (Covid-19) Pandemic. These renamings have generated passionate and even heated public debate at times, with a common refrain by some being that place renaming causes us to forget our history, or to rewrite it.

Historically, however, renaming in Edmonton is far from new. Some of the instances that may be more well-known to Edmontonians are Mayfair Park being renamed Hawrelak Park, or city roads being renamed in recognition of Edmonton Oilers hockey players – part of St. Albert Trail is now called Mark Messier Trail and Capilano Road now bears the name Wayne Gretzky Drive. But others abound: Riverside Park was renamed Queen Elizabeth Park in 1939; Beverly Jubilee Park was simply renamed “Jubilee Park” in 1989; Karl Clark Road was originally known as Research Centre Loop, the Bonaventure neighborhood was once known as Radial Park and the Brown Estate and so forth. Moreover, the development of new places on top of old ones has regularly meant renaming that place, in line with the new purpose for which that area was built; for example, when a new neighborhood is designed, often the new name is connected with the place in which it is situated in some way (such as Gold Bar, named for the Gold Bar Farm which once stood there), but often it is simply a new name unconnected with Edmonton’s history in any way (such as The Hamptons).

In the city’s early history, when its urban spaces were emerging, the creation of new names was a constant. One of the first major renamings occurred after the amalgamation of Edmonton and Strathcona. In 1914, a new “Edmonscona” plan proposed a mixed numerical-name system so as to integrate the street systems for the two towns. While there was quite widespread support for the Edmonscona plan, there were many who preferred the utility of numbered streets. This plan had vociferous opponents: one critic of the numerical system referred to it as “the penitentiary system of numbering.” Nevertheless, the latter system was adopted, with a veritable upheaval of place names being the result. Among the most notable instances of non-numerical names that remained from this plan was Jasper Avenue, named for North West Company trading post manager Jasper Hawes. However, despite the efficiency of the numbering system, many still lamented the loss of the old street names.

Much of the place-naming in Edmonton’s early urban history was the product of its British associations, which certainly reflected the sentiments of the city’s political leadership at the time. Among the first such major renamings was the changing of Portage Avenue to Kingsway Avenue, which received this title as a result of the 1939 Royal Visit of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth (this occurred at the same time as the renaming of Riverside Park to Queen Elizabeth Park, mentioned above). This Royal Visit to Canada was a substantial event, with the King and Queen travelling the breadth of Canada amidst the tensions leading up to the Second World War. The change of the street’s name occurred just days before their visit, in order to facilitate their procession.

Also reflecting the British influence on Edmonton was Patricia Square, or Patricia Park, which lies on 94th street and 109a avenue. Named for Princess Patricia, this land lies in the heart of what became the Italian district of Edmonton. The McCauley neighborhood more generally was traditionally an immigrant district of Edmonton, especially since 97th Street was a major thoroughfare early on, the streetcar line ran nearby, and over time, many ethnic churches serving Edmonton’s French, German, Danish, and Dutch communities developed in the area. Edmonton’s Italian community centered on this part of the city and sought to consolidate the “Little Italy” identity of the neighborhood by renaming Patricia Park as Giovanni Caboto Park. Caboto was an Italian navigator and explorer who landed in North America in 1497 (his name was once often anglicized as John Cabot). The new name came into effect in 1981, and as with other renamings, reflected the changing character of the area. What this new name represents – as has occurred in other parts of our City – is a recognition of other parts of Edmontonian and Canadian history, aside from English settlement.

Place renaming in Edmonton has not always been a result of government or community initiative, however. A private structure that was long an Edmonton institution and changed its appellation multiple times throughout its existence, was Northlands Coliseum – former home of the Edmonton Oilers. When it was opened in 1974, the giant circular arena was known as Northlands Coliseum, later more commonly called the Edmonton Coliseum. Corporate sponsorship by Skyreach meant that the building became known as the Skyreach Centre, and when Rexall bought the naming rights to the building, it was known as Rexall Place. When the “House that Gretzky Built” was shut down in 2016, “Rexall Place” was the name that was usually saluted.

While Indigenous place names have long been a part of Edmonton history (the word Saskatchewan derives from the Cree word “Kisiskatchewanisipi,” which means “swift-flowing river”), renamings have occurred in recent decades to reflect a renewed appreciation and recognition of local Indigenous communities and history. This part of history was long sidelined by the settler society that held control of naming places at the “official” level. For example, part of what became known as the Blue Quill neighborhood was once called Edmonton Place. The neighborhood was established in 1974 and is named for the nehiyawak (Cree) Chief Blue Quill, who traded in Edmonton, and lived on the Saddle Lake Indian Reserve, established in 1889. In 2015, a portion of 23rd avenue that connects Edmonton with the Enoch Cree First Nation was renamed Maskêkosihk Trail, a Cree word that means “people of the land of medicine.” This greater representation and acknowledgement is important for celebrating and appreciating the Indigenous history of this place, and is a step in the process of Reconciliation.

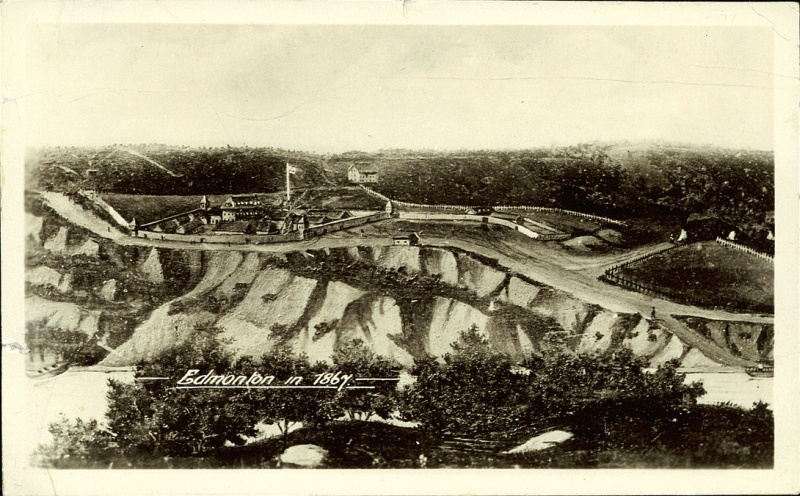

Perhaps most fundamentally, the development of Edmonton itself was a process of – among other things – renaming a place. The name Edmonton was first applied in this area to designate the Hudson’s Bay Company fort, the final iteration of which was perched on what is the Legislature grounds today. Edmonton is an old English term, which as far as historians can tell first appeared in 1086 at “Adelmetone,” which the Oxford Dictionary of British Place Names notes referred to the “Farmstead of a man called Ēadhelm.” To the Cree speakers of the area, Edmonton Fort was known as amiskwaciwâskahikan (Beaver Mountain House, often also called Beaver Hills House), a name derived from the pre-contact name for this place – amiskwaciy, the Beaver Hills. Since Edmonton as a name was not derived of local peoples, it represents a renaming in itself and one that reflects the colonization and settlement of these lands.

In short, renaming is not a new practice in Edmonton. It has occurred for a variety of reasons and with differing motivations. Even today, we know the City of Edmonton by many names. Many people refer to Edmonton as The River City, The Festival City, and in a cheekier spirit, as Deadmonton. The nickname “City of Champions” still lingers, despite its formal removal in 2015. As we have seen, place renaming, or employing multiple names for a single place, does not cause us to forget our history so much as it invites us to remember other histories. There are numerous libraries, museums, archives, organizations, and people which are there to help us remember history. Naming places is primarily an act of commemoration, appreciation, celebration, or sheer practicality, and history does not simply vanish as a shared public space is renamed.

Connor J. Thompson © 2021

Suggested Reading

City of Edmonton Heritage Sites Committee. Naming Edmonton: From Ada to Zoie. Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 2004.

Suggested Viewing