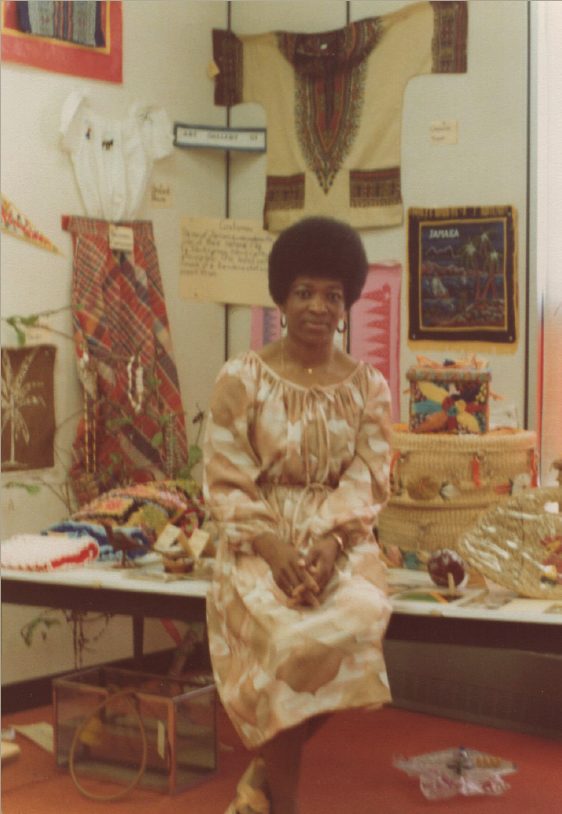

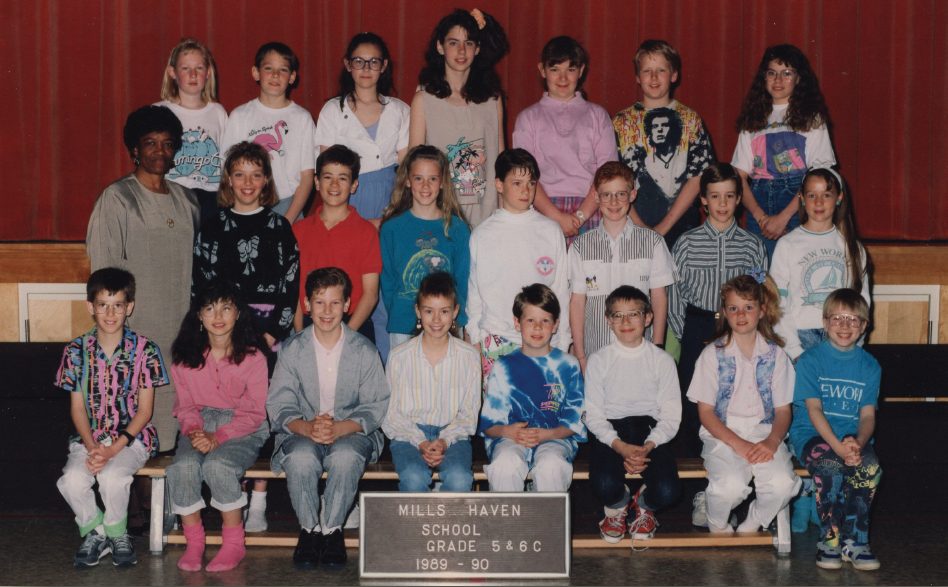

Within the larger group of Caribbean immigrants, several internationally educated teachers came from different islands to fill the need for teachers in Alberta.

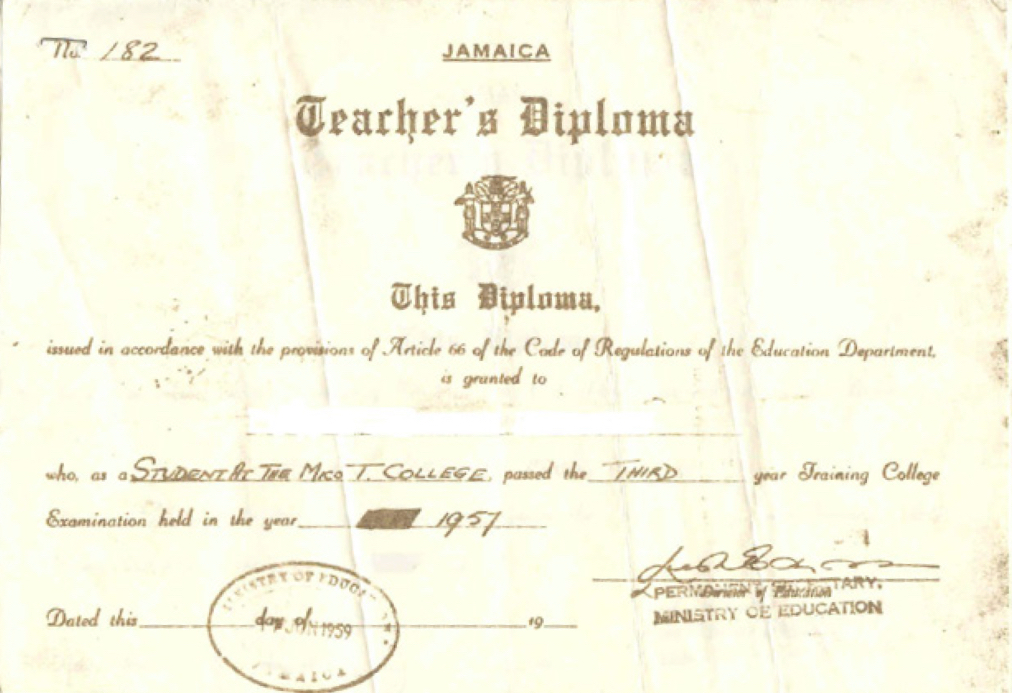

There are no detailed records of how many teachers came to Canada, and specifically Alberta, in the late 1950s and 1960s. But, based on the interviews, conversations and archival research, we can estimate up to 70 Caribbean teachers settled in Alberta. Some of these teachers formed a Mico Old Students’ Association that is associated with Jamaica Association Northern Alberta. Mico University was founded in 1835 in Kingston, Jamaica.

“Well, when I came here … Alberta was having a teacher shortage. They were advertising […] especially in Jamaica for teachers, and we had a very good friend who was at York University here and was already teaching.”

A common source for information were advertisements sent out across the British Commonwealth. At times, the Canadian government sent administrators abroad to select and interview teachers.

“Back in Jamaica, we had a bunch of Canadians coming down to interview teachers. It was all over the news media.”

“… I graduated from Mico in 1962, and I taught for a year in Jamaica, and then I was seconded to [another Caribbean island], and I worked for two years while I was in [other Caribbean island] – [I] saw this ad in the papers recruiting teachers for Canada…and I saw this as an opportunity to continue my (laughs) exploration, instead of going back to …”

Travelling abroad expanded social horizons and generated cultural capital through access to information and contacts. This encouraged many to immigrate to Canada.

“What made me decide to come to Canada? Alberta? Number one, I traveled to Britain on a scholarship… I finished my year and met some great people there, students from all over the world… students from Canada, and we became very good friends– at the time there was a kind of exodus from England to Canada. You know, graduates – because there were jobs available.”

Some learned of the need for teachers by word of mouth and friends already in Canada:

“Well, my wife had a friend who came to Canada and that friend got some info about Alberta especially, wanting teachers. So, she sent her info about Alberta; about the place and need for teachers. We decided that … what if we go to Alberta and we didn’t like it. So, it was decided that one of us should go and just in case we don’t like it then that one person could come back.”

Many teachers came with landed immigrant status, the first stage towards citizenship.

“You’re allowed to work and participate in society. Then at the end of five years you could apply for your citizenship if you so desired.”

These teachers were able to enter Canadian society as professionals due to teacher shortages following the early stages of teacher professionalization in the 1960s. Had the teaching profession been fully regulated, these teachers may never have got the chance to immediately use their teaching skills in classrooms while continuing to upgrade and gain degrees.

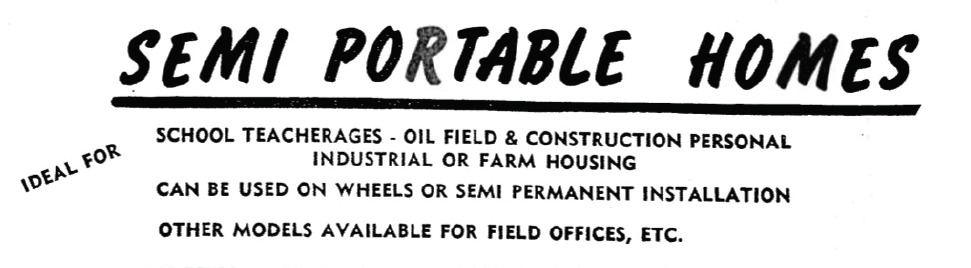

Locations & Conditions of Teaching

Advertisements in Alberta Teachers Association (ATA) magazines and newspapers during the late 1950s and early 1960s show that the demand for teachers was highest in the Northern areas of Alberta and often within Métis communities.

As J.W. Chalmers points out in his 1962 article “The school in the forest”:

“[T]hese schools lay east of the Peace River to the Athabasca and the NAR [Northern Alberta Railway], and North of Lesser Slave Lake all the way to Fort Fitzgerald. Many had only recently been elevated from the humble status of mission schools. Half a dozen others had existed for 20 years or so as Métis Colony schools. Some were located in tiny settlements; a few in ancient fur-trading centres.”

Several interviewees described their experiences teaching Métis and other students in isolated northern communities. Such isolation from the mainstream of teaching could result in different financial outcomes for retirees.

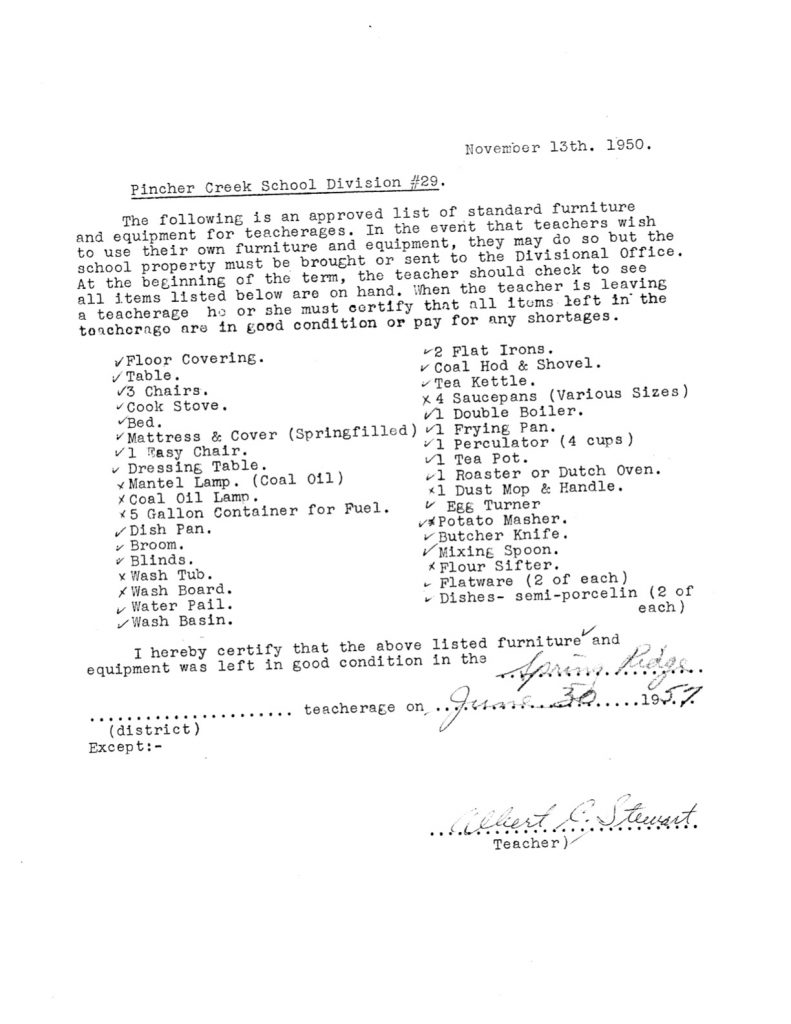

“All the teachers live… on the school [site]…and they call it teacherages. …. and that’s all we saw, no houses or anything, just teacherages…. – It was quite comfortable, and they furnished [it].”

One teacher highlighted the degree of culture shock he experienced when moving to an isolated northern community:

“… the strangest thing was that the children came to school on a horse-drawn carriage (they never had school buses). And that was their bus for the first two years, I think. And the horse goes around the houses, bring the kids to school, and take them back in the afternoon. We always said Geee!!… we don’t have this in Jamaica. This happened winter and summer for the first two years and then they got the buses. You can understand because the roads up there were not conducive to have a motor vehicle travel on them. It was just an awful, terrible road.”

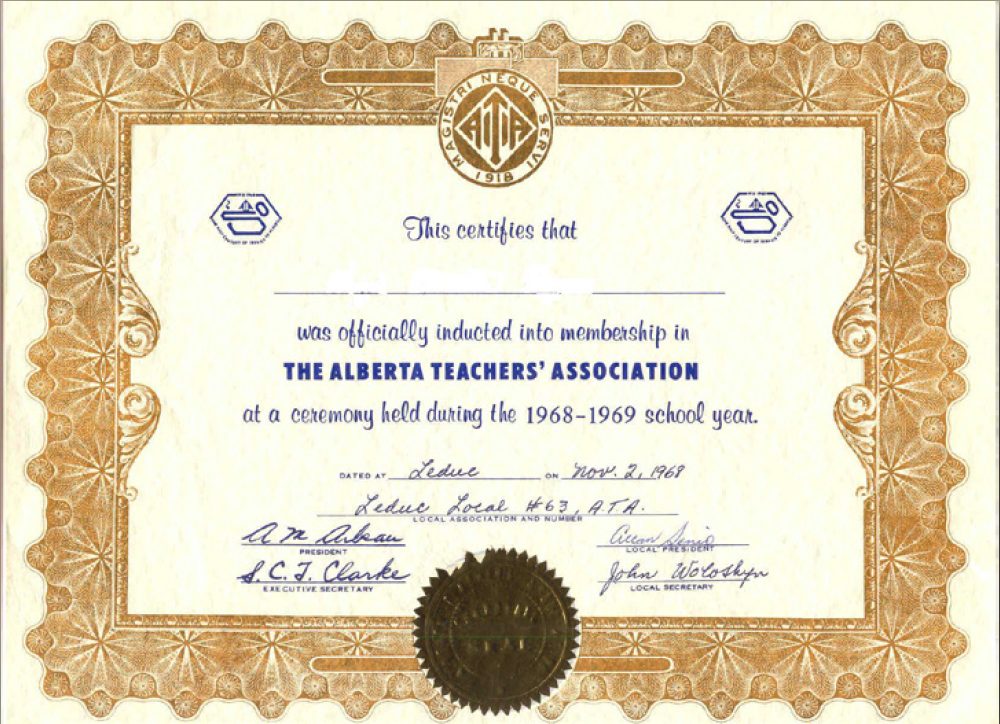

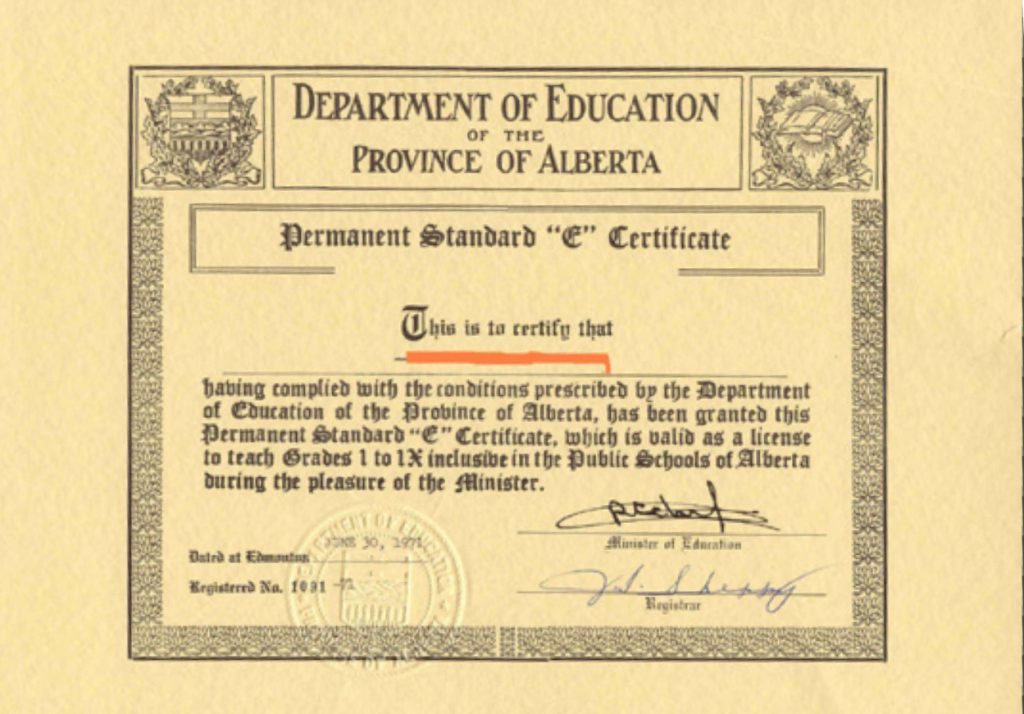

Certification

At times, the provincial nature of education was a barrier to Caribbean teachers gaining full recognition of their teaching credentials. The following interviewee shared how his experiences in Quebec were not recognized outside Quebec:

Teacher: Well, I had an interim [certificate] from Quebec. That was good for Quebec but no body approved it in Alberta.

“Letter of Standing is issued as a permit to teach; it gave you the OK for you to go into the classrooms….Letter of Standing is very brief and interesting. It certifies that you are ok then you apply for the Letter of Authority. But, when I went to school on my first job, I didn’t realize that I wasn’t alone. All the other teachers have started – only the principal alone had a BA or B.Ed. So, I thought it was required to have a degree. I didn’t realize that I wasn’t alone. Even the Vice-principal didn’t have a degree. They went to what was called a Normal School.”

The number of teachers with a degree changed over the years so that one teacher stated:

“When I came to Canada in 1961 lots of teachers in Alberta never had a degree. Even some Principals did not have it and this particular guy… he never had a degree. And it is so funny that nearly everybody else, always foreigners, had one more degree.”

It was not just teacher education in the Caribbean that was devalued by the provincial authorities but the experiences gained in K-12 schooling were also unfortunately deemed deficient. Despite initial disappointment with the evaluation of their previous teaching experiences, these educators grasped the opportunities to further their own education and improve their salaries and future.

Guiding questions

- Did this virtual exhibit challenge your perceptions of Alberta’s history? Did it affirm your understanding of this history of this place? What surprised you?

- What patterns did you see in this exhibit?

- Have things gotten better regarding racism against & the stereotyping of Black Albertans over the past 100+ years? Have things gotten worse?

- After exploring this virtual exhibit, what is the one thing you will remember? What is one lesson that you will apply to your everyday life?