Surrounded by rows of towering tomato, cucumber and pepper plants in a greenhouse near Edmonton, I marvelled at tapas from locally sourced ingredients at an Alberta Open Farm Days dinner. As I enjoyed inventive and delicious small plates brought to the long table under the glass roof and lazy August sun, I wondered how the first city dwellers obtained their veggies. I wanted to know how the produce grown then reflected the times, the needs, and the tastes of Edmonton’s early citizens.

The first settlers lived in Fort Edmonton. As early as 1813, reports show that barley, turnips, cabbage (2300 heads) and potatoes were grown. Sixty years later, a surveyor commented, “barley, oats and potatoes, etc. can be raised here although wheat is not a sure crop, frequently being injured by summer frost.”[1] Despite this observation, by 1893 settlers were attracted to the area, owing to the success of Red Fife Wheat, champion at the Chicago World’s Fair the year before.

In an early map of the Fort, twice the land is given to cultivation as to all the first four buildings combined.[2] A traveller in 1872 remarked that “the same land has been used for the farm for thirty years, without any manure worth speaking of being put on,”[3] which suggests the fertility of the loamy soil. The Fort gardens were situated on either side of what is now the 105th Street bridge on the north river bank flats, extending to the Rossdale power plant and Indigenous burial grounds. Rossdale Flats, as recorded by Anthony Henday in 1754, was originally a Cree camping ground, Otinow – “a place where everyone came,” near today’s ReMax Field and the site of the 2020 Prayer and Community Camp Pekiwewin.

Donald Ross, the namesake of Rossdale, took over the Fort gardens in 1874, and subsequently developed the land that would become his on River Lot 4 in the 1880s. He cultivated the domestic strawberry in 1889, competed in national agricultural exhibitions and in 1895 erected the first greenhouse (heated by a boiler), to feed guests at his Edmonton Hotel, across the river from John Walter’s ferry dock.

As the town of Edmonton grew, and then became the capital city of the province in 1905, other sources of produce included farmers from both sides of the river who peddled door-to-door and, beginning in 1900, provided truck sales six days a week at the outdoor Market Square where the downtown Stanley A. Milner Library is today.

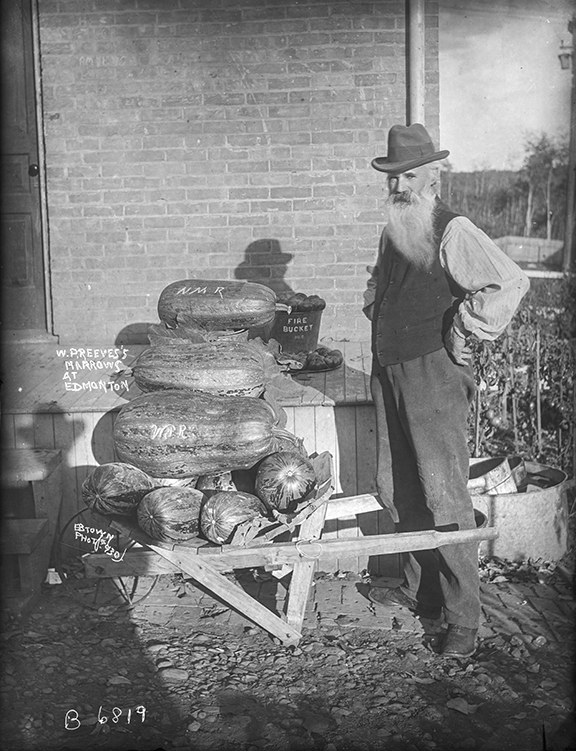

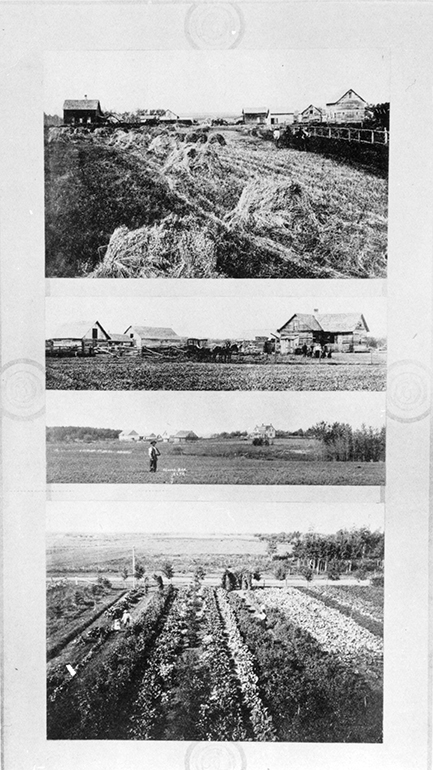

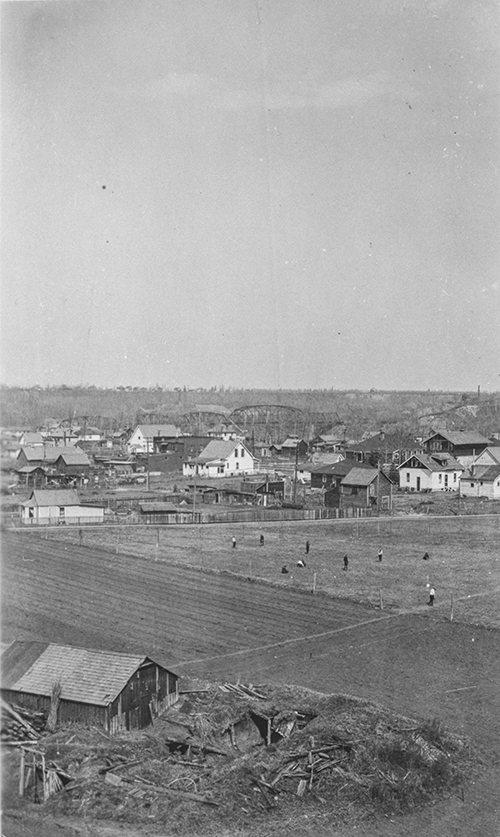

Farmland along the river eventually gave way to houses. MacGregor, in Edmonton: A History, describes early city properties: “On the back of most lots, with a wisp of hay curling out of its loft and a pile of manure behind it stood a stable big enough for two or three horses, and sometimes a cow… Gardens, which supplied vegetables all summer and potatoes for the whole winter filled the rest of the back yard. In many cases, potatoes decorated the front yard.”[4] Besides produce that citizens grew at home, Edmonton had “the most modern and largest greenhouse west of Toronto”[5]according to a Chamber of Commerce “Facts About Edmonton” brochure of 1907. A Dominion Exhibition poster from 1906 declared, “The Sun Always Shines in Alberta.”[6] Edmonton claimed to be warmer than Calgary, less windy than Saskatoon or Winnipeg, and plants grown here were considered less susceptible to diseases or pests than in British Columbia or Ontario. By 1915, gardeners in Edmonton also had a local seed supplier, Pike & Co. Seeds.

Institutions were also involved in market gardening. Situated where Commonwealth Stadium is today, the original Penitentiary Grounds (1903-1921) ran a prison garden, which contributed produce to the Royal Alexandra Hospital after 1916. The City Market grew to include a building, and new quarters, and “many people rented land from the city to grow vegetables” for their families and also to sell.[7] Organized by the Edmonton Horticultural Society, a Vacant Lot Club cultivated 8000 vacant lots in 1918. A series of Chinese gardeners leased land from the J.B. Little Brickworks, north of Riverdale School between 88 and 92 Streets at 101 Avenue. Yet You is remembered for adding gates to the fences for children to walk past “row upon row of lovely cabbages, radishes, lettuce, corn and carrots” as a shortcut to the school.[8]

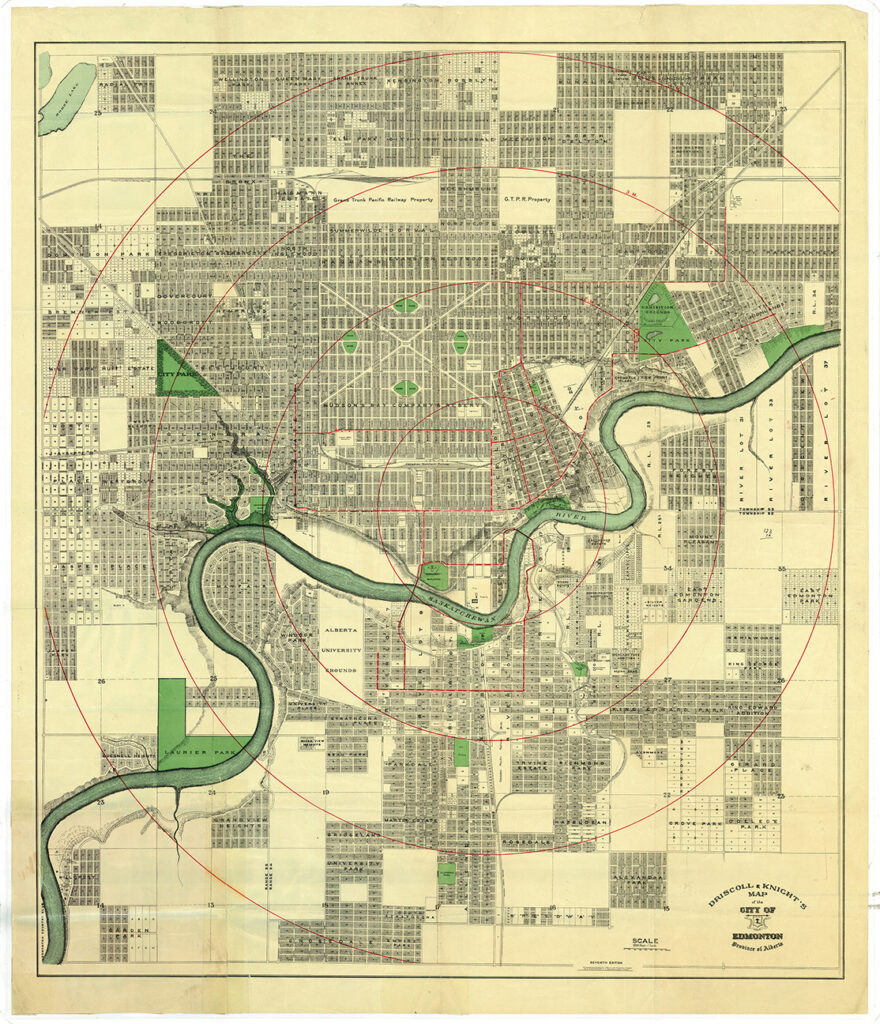

By 1935, there were fifteen Chinese gardens “strung out along the North Saskatchewan River valley from Beverly in the east to Government House in the west.”[9] A commentator in the Edmonton Journal enthused about “a veritable Chinese tapestry worked out in rectangles of harmonious greens, sea green, sage green, olive green, and the delicate apple green of lettuce beds.”[10] Chin Lock’s gardens were on the former site of John Walter’s lumber business. Jung Suey and Gee Gut cultivated the riverfront now occupied by Kinsmen Park. Hong Lee developed Groat Flats until the expansion of Victoria Golf Course and the Groat Bridge. Bark Ging Wong operated in Calder.

Hop Sing and another man, remembered as extremely hard workers, operated a huge market garden before and during the war that spanned over six city blocks in Belgravia (including the land now occupied by my house, built in 1949). Previously, these fields may have served as a Depression relief garden, because the Edmonton Journal reports 35 acres in five communities, 15 acres in Belgravia, cultivated by “work parties of men on relief” in 1933.[11] This open tract of land, north of 76 Avenue, is evident on the 1924 city map.

During World War II, victory gardens were also promoted. A government poster recommended: “Grow more foodstuffs in the garden. Can and store more vegetables and fruit. Live-at-home and help Canada’s war effort.”[12]During the war, however, “women who took jobs outside the home had less time to tend gardens and preserve produce for winter consumption” and subsequently “out-of-season vegetables became available year-round” at supermarkets.[13]Lawrence Herzog posits that in 1955, the first enclosed mall in Edmonton, Westmount Shopper’s Park, “catered to changing shopping habits and a shifting preference for purchased over homegrown produce.”[14] Megastores sprouted in Edmonton in the 1980s. The Edmonton Food Bank also opened in 1980, the first in Canada.

By 2000, there were sixty greenhouses within a 100-mile radius of Edmonton, and today, there are a dozen city markets in Edmonton and surrounding areas. To date, there are also 98 community gardens and 58 gardens in schools supported by Sustainable Food Edmonton. Urban agriculture is also evidenced by Operation Fruit Rescue Edmonton and its Micro-Orchard in the McCauley School grounds.

Since the pandemic of 2020, many people new to gardening are giving it a try. I’m taking some old-time advice from Mary Sernowski, a legendary gardener who sold at the City Market: April is potato planting month. It seems early, but if Mary’s young potato plants froze in April or May, she would wait for the next rain, and they would come up again, providing new potatoes in June.[15] As a longtime backyard gardener, I share the desire to seed the garden as soon as possible.

After months of winter, the impulse to plant and produce food in naturally rich soil, under the sun that shines 321 days of the year, runs deep and long in the history of Edmonton.

Katherine Koller © 2021

Works Cited

A Century of Gardening in Edmonton. Edmonton: Edmonton Horticultural Society, 2009.

Gilpin, John F. Century of Enterprise. Edmonton: Edmonton Chamber of Commerce, 1988.

Hesketh, Bob and Frances Swyripa, eds. Edmonton: The Life of a City. Edmonton: NeWest, 1995.

Hole, Lois. I’ll Never Marry a Farmer. St. Albert: Hole’s, 1998.

MacGregor, J.G. Edmonton: A History. Edmonton: Hurtig Publishers, 1967.

Merrett, Kathryn Chase. A History of the Edmonton City Market 1900-2000. Calgary: U of Calgary Press, 2001.

Merrett, Kathryn Chase. Why Grow Here: Edmonton’s Gardening History. Edmonton: U of Alberta Press, 2015.

Rossdale Historical Land Use Study. Edmonton: City of Edmonton Planning and Development Department, 2004.

Shute, Allan and Margaret Fortier. Riverdale. Edmonton: Tree Frog Press, 1992.

Swindlehurst, E.B. Alberta Agriculture: A Short History. Edmonton: Department of Agriculture, 1967.

[1] Rossdale, 58.

[2] Rossdale, 41.

[3] Rossdale, 67.

[4] MacGregor, 143.

[5] Gilpin, 50.

[6] Swindlehurst, 22.

[7] Merrett, A History, 66.

[8] Shute and Fortier, 106.

[9] Merrett, Why Grow,198.

[10] Merrett, Why Grow, 197.

[11] Merrett, Why Grow,150.

[12] Merrett, A History, 98.

[13] Merrett, Why Grow, 159.

[14] Quoted in Merrett, Why Grow, 159.

[15] Hole, 80.